|

158 Lee Avenue ph: +1 416-691-2516 info @ archimuse.com Join

our Mailing

List.

published: March 2004 |

Chicago WebDocent: Bringing Museums to the Digital Classroom — On-line Content Management and Presentation System (CMAP)

Julia Borst Brazas, Benjamin Lorch, and Sean York, University of Chicago, USA

Abstract

This paper describes Chicago WebDocent Project's newly developed on-line Content Management and Presentation System (CMAP), a database-driven, Web-based curriculum production tool that facilitates the development of high-quality on-line materials through partnerships between Chicago Public School teachers and several Chicago museum collections. Using CMAP, teacher content-creators can outline and organize lessons via a Web-based interface by inserting lesson text and digitized museum media. Students who use the resultant Chicago WebDocent lessons engage museum content guided by a story-telling character (or docent). They read text, explore high-resolution images, watch video, listen to sounds, and learn through interactives. Students also have ready access to glossary terms and definitions with standard pronunciation symbols, audio pronunciation clips, and illustrative media all within a unified lesson interface.

Keywords : On-line Curricula Creation, Institutional Partnerships, Educational Outreach, Collaboration, Public Schools, Digital Museum Content, Learning Technologies, Community Informatics.

Introduction

The Content Management and Presentation System (CMAP) developed by Chicago WebDocent system is an excellent example of community informatics at work in Chicago. After several years of work with its partners, CMAP embodies the cultural expertise of museum curators, the educational expertise of teachers, the technical expertise of the Chicago WebDocent's programming staff, and the community outreach/development expertise of Chicago Public Schools / University of Chicago Internet Project.

The museum partners Chicago Web Docent works with each have different priorities, policies, and practices regarding documentation of their collections. One challenge comes in acquiring, digitizing, storing, and accessing content from various museum partners. At the same time teachers are generally not experienced in interpreting objects and images for educational goals, nor in using technology to develop curriculum . We have achieved the twin goals of making digital museum content and teacher content-creators central to the development process by implementing CMAP.

About the Chicago WebDocent Project

The Chicago WebDocent Project (CWD) (http://www.chicagoWebdocent.org) is a collaboration of the University of Chicago, the Chicago Public Schools (CPS), and eight Chicago cultural institutions to develop on-line curriculum modules featuring Chicago museum and library collections, (the Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago Historical Society, DuSable Museum of African American History, Field Museum, Museum of Science and Industry, Newberry Library and the Oriental Institute).

CWD lessons are created with urban school children in mind and employ a cross-disciplinary approach to learning through storytelling. Teachers write lessons as first-person narratives in the guise of a docent who is usually a peer of the student who will read the lesson. The docent character gives a personal account of a historical event, era, or scientific discovery while sharing details and particulars of his or her life. Storytelling personalizes and humanizes historical events and makes them appealing to students because the details of the docent's life and experience become the anchors students connect to formal learning goals. The historical story-lesson approach, coupled with the interactive features of CWD, supports language arts standards for reading, writing, researching, and developing word analysis strategies. Likewise, lessons use the context of the story to support math and science standards through simulations and animations.

Since it was founded in 1999, Chicago WebDocent has published 6 curriculum modules focusing on social studies and science topics for grades 3-8, integrating primary resources and cultural material from our institutional partners.

- Transportation in the History of Chicago, Grade 3

- A History of Illinois, Grade 4

- Show Me the Money! Economics in American History, Grade 4-5

- Table Manners: Basics of the Periodic Table, Grade 6

- Communication in the Ancient World, Grade 6-7

- Voice of America: the People, the Press, and the Constitution, Grade 7-8

Three new modules are currently in development for grades 6-8: Africa Today, Origins of the Elements and Stories of Their Discovery, and Where Do the Elements Come From? The Chicago WebDocent Project is funded by the Chicago Public Schools, University of Chicago, The U.S.A. Education Charitable Trust, and NASA.

CWD is staffed by two full-time employees of the University and two part-time student workers. All phases of the curriculum development process are contracted to full-time CPS teachers. In addition, we contract Web software developers to build and improve server- and client-side software that support our efforts. Rounding out the personnel are a host of volunteer museum educators, archivists, curators, and University of Chicago faculty who participate in teacher training and serve as expert readers of curriculum modules to ensure intellectual quality. The process for developing CWD curriculum modules draws upon many relationships, beginning with the Chicago Public Schools / University of Chicago Internet Project (CUIP) and extending outward to the community.

Strong Connections to Local Education Communities

The Chicago WebDocent Project is an initiative of the Chicago Public Schools / University of Chicago Internet Project (http://cuip.uchicago.edu/). Since 1997, CUIP has partnered with local schools neighboring the campus of the University on Chicago's South Side. Currently CUIP works on-site with 26 schools with the goal of making information technologies an integrated and effective part of teaching and learning in classrooms, libraries, and computer labs. The six-member full-time staff of CUIP are joined by 45 part-time paid students who work in five areas:

- technology leadership among principals;

- hardware and networking equipment provision;

- technical support;

- teacher training and professional development;

- integration of technology and curriculum.

A key to the success of the WebDocent Project and CUIP alike are the strong working relationships and trust that have formed over the years. CWD enjoys ready access to teachers and students in the CUIP schools for field-testing curriculum modules and can observe first-hand the challenges involved in technology integration. The relationships held by CUIP and CWD with teachers, school technology coordinators, principals, and district administrators have helped ensure that our on-line curriculum offerings meet the needs of the schools while appealing to urban public school students. (For more information on the Chicago Public Schools / University of Chicago Internet Project and the Chicago WebDocent Project, see 2003 International Cultural Heritage Informatics Meeting paper 101C, Key Success Factors for Museum-University-Public School Partnerships.)

Core Mission: Building Bridges

A core mission of CWD is fostering relationships between the formal and informal education communities. For each curriculum module developed by CWD there are numerous working relationships that form bridges between the schools and cultural institutions.

Figure 1: Working relationships in the development of a Chicago WebDocent curriculum module

The cultural institutions in the WebDocent collaboration are a diverse group. While they share the common goal of extending their educational outreach through technology, they differ in physical size, collection scope, and staffing levels. There is also wide variation with regard to active digitization programs. CWD's approach has been to work with the institutions at their levels in a service orientation to encourage participation in the project.

Problems

The number of contacts in the institutions has expanded every year as the CWD gains more attention and working relationships are strengthened. Because CWD works so closely with a multitude of educators, experts, and institutions, the process of creating a module is time- and resource-intensive. Aside from managing the various relationships involved in the development of a module, our production process involves many steps. As we ramped up our production schedule to meet the goal of producing two modules per year, we identified problems in our process:

- It was difficult for teachers to access museum materials while writing their lessons.

- For weeks or months, teachers would not see the final form of the lessons they wrote.

- The process of writing, editing, and producing a lesson was cumbersome, redundant and time-consuming.

- Image production involved many steps, and final images were too small to afford the detail that engages students in active viewing.

- There was no good system for reuse of work such as images and dictionary terms.

The result was that teachers felt disconnected from the process, and CWD staff spent too much time on mundane production processes and less and less time on our core missions: supporting teachers, building teacher and museum relationships, weaving content from multiple museums and libraries into the curriculum, and creating rich, imaginative and engaging educational experiences for Chicago Public Schools students.

Solution

In order to re-tool our production process, we needed to empower and engage teachers by giving them better access to digitized museum and library collections, and show them the results of their work immediately. We needed to streamline lesson writing and production and optimize media management in order to liberate CWD staff to focus on core missions. The solution was to build a database-driven system with an easy-to-use front end for both teachers and administrators, one which would also deliver the finished lessons to students in the Chicago Public Schools. We applied the imaginative moniker of "Content Management and Presentation System, and the CMAP project was born. One year later CMAP is a reality, and we have made great progress towards our goals.

CMAP Overview

CMAP consists of two content databases and one usage-tracking database (MySQL). Of the former, the first is the media database which accommodates images, sounds, video, and interactives, as well as the associated metadata. The second is the lesson database which keeps track of all lesson elements such as page text, dictionary terms, journal questions, and customized media captions. The third database tracks student usage of lessons, including what museum objects were accessed during a lesson.

The system has four role-based interfaces: Writer, Reviewer, Administrator, and Student. There are Flash-based graphical interfaces for Students and Writers, while the Administrator and Reviewer Interfaces are HTML (Hypertext Markup Language). All interfaces communicate with the databases via PHP middleware. (PHP is a recursive acronym for "PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor, a widely-used Open Source general-purpose scripting language that is especially suited for Web development and can be embedded into HTML. See figure 2.)

Figure 2: Students, reviewers, writers, and administrators access and modify the core lesson and media databases via PHP middleware

CMAP's relational database architecture allows CWD staff, teacher-writers, students, and expert reviewers to view, enter, and edit content in the ways that best suit their particular roles.

Figure 3

CMAP creates efficiencies of labor by minimizing redundancy in the production process and allowing reuse of lesson materials. It empowers teachers by providing them with sophisticated yet intuitive tools for developing their lessons and with direct access to digitized content from multiple cultural institutions. Most important, it helps us achieve our goal of delivering engaging, on-line curriculum materials featuring the collections of Chicago's outstanding museums and libraries.

The Student Interface

In 2001, we began development of a Flash-based template to present the lessons. Over the next two years the template was improved as it underwent multiple field tests in the schools. The resulting interface design combines the elements of a storybook with interactive features

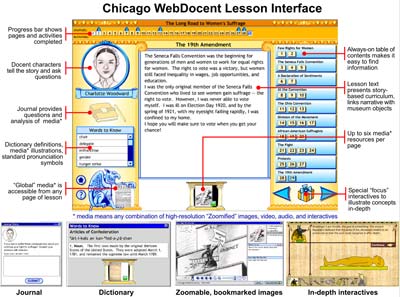

Figure 4: The Chicago WebDocent Lesson Interface featuring many interactive components

The latest version of the Student Interface includes new and updated features and makes the leap from static text files to dynamic database-driven content in CMAP.

The student using CWD chooses an assigned lesson within a curriculum module and is greeted by the docent character, who introduces the lesson topic. A lesson may include up to 10 chapters, or sections. Within each section there are 1 to 5 pages of text. The docent appears on every page of the lesson and can be animated to prompt students to explore the interactive features on the page or to provide feedback. Students can move between pages using a forward- or back-arrow button. They can also navigate through the lesson by clicking on page numbers listed in the sections.

Media Interaction

Lesson pages include digitized images of primary source materials from our institutional partners. This content is presented as a clickable museum icon that opens full screen to reveal a high resolution image. We have incorporated a Zoomify viewer into our template so that students may zoom within this window to closely inspect and navigate images and texts (http://www.zoomify.com). Each image window includes a caption, source information, and perhaps bookmarks to specify areas of an image and text identified by the teacher for special attention. The image window can also include video.

Journal Interaction

Lessons include an on-line journal. The journal appears "grayed out until students activate a page where a journal question appears; then the journal pops open to signal the presence of a question. Students answer the on-line journal questions and print responses at the end of the lesson or class period. The journal can include images, audio, and video in addition to text that presents open-ended questions, quizzes, and numeric or math word problems.

Dictionary Interaction

Definition terms are listed on the page in the Words to Know box. The complete listing of vocabulary words for an entire lesson is accessible on every page. When a vocabulary word appears in a lesson for the first time, it is underlined and clickable. Clicking on an underlined word or one listed in the Words to Know box activates a window containing the definition and pronunciation, using standard dictionary symbols. The definition window can include images, audio, and video.

Interactive Media Elements

Some lessons include interactive media elements, which are key enrichment activities that use the context of the story to integrate interdisciplinary skills and knowledge standards. Interactives present a simulation or problem-based scenario in which students apply what was learned in the lesson to arrive at an answer, solution, or new idea. Students use the keyboard or mouse to participate in simulations, answer questions, manipulate screen items, or complete tasks, among other uses. See figure 5.

Figure 5. Sample Chicago WebDocent Interactive: Make Your Own Mummy

]Both students and teachers have cited the interactives developed for CWD materials as exciting and effective. The experiences that interactives offer are difficult or impossible to achieve with traditional classroom media, and help develop students' skills as information seekers, problem solvers, and visual thinkers.

A wrapped gift box on the page signals that there is an interactive media element present. Some lessons have a global interactive media element that may be accessed from any page within the lesson by clicking on the gargoyle icon. For example, students using CWD's science lessons use an interactive Periodic Table that appears as a global media element on every page.

Teacher and Parent Users

While the intended audience is students, CWD modules include features of specific interest to teachers. Each curriculum module includes a comprehensive teaching guide. In addition, each lesson includes its own teaching guide, suggestions for extending the lesson offline, and links to high quality Web sites on eCUIP, a digital library initiative of CUIP (http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/ecuip). Instructional scenarios for using CWD materials in a variety of classroom teaching arrangements; such as electronically supported lecture, individual work among students, or cooperative learning, are described for teachers.

Each curriculum module contains 6-12 lessons, with each lesson equal to approximately one hour of study. CWD lessons are structured so that teachers can flexibly use chapters within a lesson or cover the entire lesson in single class session. Strategies for using CWD lessons incrementally are included in the teaching guide.

The CWD interface helps teachers monitor student work through a progress bar. The progress bar appears at the top of the page and indicates how many pages the student has visited, and whether he or she completed the interactive or journal activity on that page. This bar also functions as an alternate navigation method, allowing teachers or students to click on a page number to move to a desired page.

Many Chicago WebDocent modules are portable to Internet-connected homes where students can follow up on their classroom activities or explore the site further, with or without parental support.

Administrator Interface

Before a teacher begins writing, CWD staff create an entry for the lesson in the database and associate it with a module, manage users and permissions, and add media with metadata.

Adding Media to the Database

We add media, including high-resolution images from our institutional partners, to the database using a Web-based interface. Images are automatically processed using a custom server script that creates multiple versions at various resolutions, including a Zoomify-enabled version. Images can be uploaded to the server over the Web from a client machine, or placed on the server locally and batch-processed overnight.

Metadata

The media database includes approximately 30 searchable metadata fields. Most of these are mapped to a subset of VRA Core and Dublin Core fields, while the others are specific to our system and include fields such as Date Acquired, Method Acquired, etc. A simplified search function is available in the Writer Interface.

The Writer Interface

CMAP provides an interface for writing lessons and accessing media elements so that teachers can now create and instantly preview their lessons on-line. Teachers can use the Flash-based Writer Interface to enter the text of a lesson directly into the lesson database. They can drag and drop sections and pages in the outline view to rearrange the lesson as they work. To add desired elements to each page, they can search and select objects, images, texts, sounds, video, and other media elements and incorporate them into the lesson using a drag-and-drop interface. High-resolution images can be "bookmarked to bring attention to specific details. These features appear in a unified interface, making CMAP a user-friendly tool for developing lessons. The ease with which teachers can add digitized museum and library resources encourages them to enrich every page in their lesson with media. We have trained several teacher-writers in the use of the CMAP Writer Interface, and they are now using the system. The early results of this process are very promising.

Searching for Media

Through the Writer Interface, a teacher can search the media database by Title, Description, Subject, Source, Creation Date, Creation Period, and Media Type. The search results show image thumbnails and metadata, and can be previewed within the Writer Interface. A simplified search that includes the fields mentioned above is provided within the lesson creation interface. A more advanced search is available through the Administrator Interface.

Adding Media to a Lesson

Once a teacher finds the best image, s/he can add it to the lesson using a drag-and-drop, shopping-cart-like interface. Multiple media can be added to pages, journal questions, and dictionary terms. A global media element can also be added to the tour, such as the Periodic Table, the Constitution, or a map that can be accessed from any point within the lesson. Teachers can refer to a special tab which shows them recommended images for their lesson. They can also request an image that is not in our collection, so that CWD staff can obtain it from a museum partner.

Viewing and Bookmarking High-resolution Images

The Zoomify viewer incorporated into our template allows high-resolution images to be viewed in a streaming fashion over the Web without long download times. This is an impressive piece of functionality that allows us to present museum objects in crisp, clear detail for students and teachers to explore and learn from. Using Zoomify's Flash API (Application Program Interface), we built a bookmarking system that allows teachers to create a guided viewing experience for students, walking them through the details of these engaging images.

Docents

Teachers have creative license to develop the docent characters that guide students through the lessons. They can use the Docent Dossier to outline each character with fields such as gender, time period and geographical location, ethnic and cultural background, likes and dislikes, family members, and more. Each lesson can have multiple docents with up to two per page, and each docent character can have multiple guises. For example, a lesson could span the entire life of a character and show him or her at different ages as the story progresses. Docent artwork is created by CWD staff.

Journal Question and Quiz Creator

Writers can attach one or more questions to any page of a lesson. Questions can be of multiple types such as essay, multiple choice, true/false, etc. The quiz creator allows a writer to specify scoring method, multiple levels of feedback, randomized questions, and more. Questions can be presented in multiple formats using custom "skins.

Dictionary

Writers can select a term in the text of their lesson and search for it in our database dictionary. They can customize dictionary terms for their lesson by adding media and by choosing from multiple definitions. Entries display definitions, thumbnails as links to media, parts of speech, and pronunciations with standard dictionary symbols.

Reviewer Interface

Expert reviewers use a straightforward HTML interface to review the lessons. This displays all of the same content as the Flash-based Student Interface, but in a straightforward, printable interface. This interface also allows reviewers to annotate the lesson on a page-by-page basis. When they type comments and click Submit, the comments, along with the reviewers' user IDs and date/time stamps, are recorded on those pages. These comments show up on a tab along with the page text on the writer side, so reviewer comments can be easily integrated into the lesson. This interface is also being used by our writer groups as a collaborative module development tool.

The Impact of CMAP

CWD has achieved the twin goals of making teacher content-creators and digitized resources from multiple institutions more central to the curriculum development process by implementing CMAP. This set of technological tools has dramatically improved the management and delivery of content and will allow us to publish materials with greater speed. The key efficiency has been to remove CWD staff from processing teacher lessons as text files and uniting them with media elements before publishing them in Flash. Before CMAP, this step required about 20 hours per lesson and depended on a flow of work from the teacher to the CWD Director to the CWD Creative Director.

With CMAP, a completed lesson can easily be entered in the database in 1-2 hours, complete with definitions, journal questions, and media elements. In the Student Interface teachers can immediately preview their lessons as they develop and can refine them, adding more elements or revising image captions. Some teachers chose to compose their lessons as they enter them into the database rather than working from a completed text. While these iterations require more time, it is effort spent on the creative aspects of teacher work and does not impact CWD staff time. At this writing we have not finished our current development cycle and therefore cannot report accurately on the increased production speed; however, we believe it will be possible to complete production of a module of 10 lessons in one month.

Once media elements are loaded into CMAP, they are readily available to teachers using the interface to write their lessons. The first set of 154 high-resolution images, along with partial metadata records, was loaded into the CMAP database in approximately 4 hours. This represents a remarkable improvement in our process because images no longer need to be hand-tooled to show details or resized to fill the screen. The speed with which images can be acquired and made available is greatly reduced when content is received in digital form. Nearly all of our image content was acquired in analog form and digitized by CWD. Last year a project to acquire approximately 250 images from a partner museum required several weeks of staff time to retrieve materials from the donating institution, perform scanning, make CDs for the donor, and return the materials to the institution.

We recently piloted a process by which we acquired a set of high-resolution digital images from a museum partner who performed digitization in-house through a grant from the State of Illinois. The images came to us on CD with accompanying metadata in an Excel spreadsheet. Within a few hours of receiving these materials in person at the museum, the images and metadata were available in the CMAP database. In the span of an afternoon, CWD staff put together a short demo lesson featuring the newly acquired content to show the technology board of the donor museum later the same week.

Long-Term Goals

As a result of CMAP, goals that were in our peripheral vision have moved front and center. Advocating the benefits of digitization programs to our institutional partners is one goal, which we demonstrate through presentations to show how digitized museum and library content can be delivered as on-line curriculum to public school students. Another key goal now underway is improving training to better prepare teachers for using primary resources and material culture for teaching. Often museum and library content is illustrative in a lesson, rather than driving the lesson content itself. With the media database, a teacher can search on the term "coal" and retrieve text and images from multiple museums and libraries, interactives on coal mining, animations that demonstrate the environmental impact of mining, machinery sounds, music, or video of miners at work, so that the lesson is generated from a collection of various media. Such an array of content can be used flexibly for a lesson on science, engineering, social history, or any other learning goal.

Techniques of the museum educator are being integrated into training for teacher-writers to foster skills in working with an object or collection, images, text, documentary material, and narrative art. Likewise, CWD training for end-user teachers and field testers now includes demonstration of these techniques. Field tests have shown that teachers often ignore or spend little time with the image content; in contrast, students more frequently look at images and spend more time with them. If teachers do not engage students during instruction to observe, describe, and analyze primary sources and material culture presented in the lessons, then we are missing an important interaction that develops critical thinking skills and visual literacy.

CMAP has allowed us to refocus our goals and consider future directions. Even with production and management efficiencies, CWD still relies on a multitude of good working relationships with teachers and our institutional partners to keep the flow of content and curriculum going. Strengthening and expanding the connection between the schools and greater cultural community will remain an important part of CWD's mission as we continue to develop new efficiencies in production.