|

158 Lee Avenue ph: +1 416-691-2516 info @ archimuse.com Join

our Mailing

List.

published: March 2004 |

Digital Exhibitions from Virginia Tech's Digital Library and Archives

Tamara Kennelly Digital Library and Archives, University Libraries, Virginia Tech, USA

Abstract

The Digital Library and Archives of the University Libraries of Virginia Tech offer a rich and varied selection of virtual exhibitions. Users can learn about the black history of the university as pioneering black students tell in their own words about their experiences integrating Virginia Tech. The Timeline of Black History at Virginia Tech puts the interviews in a chronological framework with images and documentation. In addition to documenting black history, the Black History at Virginia Tech exhibition helped bring “home” to the university alumni and staff who were disaffected by negative experiences of the past. Faculty, staff, and alumni joined in the project of documenting the university's black history and took ownership of the Timeline of Black History, contributing materials for inclusion to make sure the full story was told. Other virtual exhibitions include collaborations with academic faculty and departments to support instruction and to document university and local history. Virtual exhibitions also showcase some of the jewels in the collections, such as the Civil War letters of a homesick drummer boy, Felix Voltz, and the Bloomsday cards of T. E. Kennelly. The extensive VT Imagebase offers materials for research and instruction and the building blocks for new exhibitions.

Keywords: Digital library, black history, African American, Bloomsday, collaboration, integration, Virginia Tech

Introduction

Enter the Web pages of Virginia Tech's Digital Library and Archives and stroll through historic Blacksburg, learn about the black history of the university, read the Civil War letters of a homesick drummer boy, or view sites from Leopold Bloom's odyssey in James Joyce's Ulysses. If you cannot visit the Reading Room of the University Libraries' Special Collections, the Digital Library and Archives' virtual exhibitions are open any time. They give a variety of perspectives on university and local history and offer enticing samples of the riches of Virginia Tech's Special Collections. In addition, the Virginia Tech ImageBase offers thousands of images in a broad range of subjects. With these images, including full text of many primary source materials, end-users can pursue their own research and instructional goals and even use the images as building blocks for new exhibitions.

Blacks History at Virginia Tech: An Exhibition that Grew

The Black Women at Virginia Tech Oral History Project engaged the university community and the world beyond in hearing the silenced voices of the first and early African-American women students at Virginia Tech and in expanding what Alessandro Portelli describes as the 'horizon of shared possibilities' their words offer (Portelli, 1997). Begun in 1994, the project initially was developed by the Virginia Tech Women's Center and the University Archives to uncover and reclaim through images, oral histories, and other documentation the previously hidden histories of the first black women students, staff, and faculty at Virginia Tech.

After almost 100 years of exclusion from Virginia Tech, six black women were admitted as undergraduates in 1966. The entrance of these women was almost unnoticed and was unrecorded in the university's documented history until 1993 when a black graduate student, Elaine Carter, broached the question: What about my history? Carter's question was a catalyst for efforts to locate the first black female students, beginning a project that has grown in scope and continues with exploration of the black history of the university. The initial search for black women entrants through institutional records was unsuccessful because the university did not have an official record of students' race during the 1960s. The university's Historical Data Book (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/databook/index.htm) recorded that the first black male student, Irving L. Peddrew, III, was admitted in 1953 and that Charlie L. Yates was the first black student to graduate (1958), but there was no record of the names of the first black women students in the university. Six black women who entered the university in 1966 as undergraduate students were initially identified through looking at photographs in university yearbooks. When the first black woman's face was located, a telephone call to her resulted in identification of her five classmates who entered at the same time. With their admission, there was a total of about 20 African Americans out of a student population of 9,064.

The Black Women at Virginia Tech Oral History Project traces the 1960s experiences of the university's first African American female students. Oral history interviews were conducted with five students: Jackie Butler Blackwell, Linda Edmonds Turner, La Verne (Fredi) Hairston Higgins, Marguerite Harper Scott, and Linda Adams Hoyle. The sixth student, Chiquita Hudson, died of lupus in the summer of 1967 after her first year at the university. The project aimed to 'shift the center' in the documented history of this southern land-grant university by bringing into the discourse the reflections of the previously silenced black women entrants. The United States is an especially diverse society, yet academic environments have been constructed from a socio-political context that has produced exclusionary thinking about the role of racial minorities and women in the university. To move from exclusionary to inclusionary thinking, the once silenced voices of those who are 'different' must be heard and put at 'the center of our thinking' (Anderson & Hill Collins, 1995).

Fig. 1: The Home Page of the Black Women at Virginia Tech Oral History Project http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackwomen/

The Internet helped locate one of the missing female students. An office colleague noticed Linda Adams Hoyle's photograph on the Black Women's History Project Web site, and Hoyle contacted the University Archives and was interviewed in the fall of 2000. Linda Adams Hoyle, who came to Virginia Tech in 1966 as a transfer student, was the first black female to graduate. In addition to full text of the oral history interview transcripts, the exhibition includes yearbook photographs, family snapshots, period newspaper articles, and papers and letters written by the women at the time.

The first black women students did not come to Virginia Tech intending to be revolutionaries. They came as any other student might -eager and excited, determined to do well and make their families and communities proud. Five of the first six women students were the first in their families to go to college. From the first day on campus they experienced racism. Linda Edmonds Turner said:

Some of the girls' parents' eyes got as big as saucers when they saw us. My parents would bring stuff in. You could see them [the white girls' parents] stop dead in their tracks. Sometimes when the kids would come back from breaks and the parents would bring them in, somebody would ask, 'Well, where do I get paper towels?' They thought Fredi and I were the hired help. They thought we were cleaning rooms, and we would just happen to be walking down the hall, and we'd say, 'Well no, we go to school here.' Some of the students - when their parents got here - they kind of acted like they didn't know you. When their parents were gone...they would talk (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackwomen/edmondb.htm).

When Linda Adams tried to move into the dorm, the parents of her white roommate decided that she could not room with their daughter. She ended up rooming with another of the black women students, Chiquita Hudson, who had requested a single room because she had a serious illness (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackwomen/chiquita.htm).

Upon entering, the black women immediately avoided a permission-seeking orientation. Linda Edmonds recalled,

Fredi and I just mixed right in—We did whatever the other girls did. There were little committees. There were pajama parties. We'd go. They might not have wanted us to, but we were there. We never considered ourselves uninvited. We entitled ourselves.

Fig. 2: Hillcrest Dorm, 1966. LaVerne 'Fredi' Hairston is in the first row on the left. http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackwomen/fredsnap.htm

Although such formal activities were not Fredi Hairston's style, she said she attended school dances at Virginia Tech out of a sense of political and social consciousness:

I thought it was important to show up - to be part of the community. There were so few of us we needed to. I honestly believe that there was a sense that not only do we have to do what we need to do for ourselves but so that the doors don't slam shut. So people don't have excuses to continue things the way they used to be.

The first black female students were not, as one of the women put it, 'bosom close.' The Web site gives a sense of the uniqueness of these individuals thrown together by circumstances. They had radically different interests. Jackie Butler was one of the founding members of the campus Angel Flight, the sister organization to Air Force ROTC (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackwomen/butler1b.htm). Fredi Hairston, on the other hand, became involved in the Tech United Ministries which she described as a 'shelter for most people who were the anti-war fringe when I was here' (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackhistory/oralhistory/fredhair/hairston2.html). She and Larry Billion, a white male student, co-authored Back Talk, a column dealing with controversial issues for the Virginia Tech, the student newspaper. Back Talk used a pro and con format to explore topics such as miscegenation, unions, the draft, and the war in Viet Nam. Full text of these articles, such as the 'Pros and Cons of Mixed Dating and Miscegenation' (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackwomen/miscegen.htm), are available On-line.

The interviews chronicle the struggle of black and white students to change the campus culture. One of the big issues for the black students was the prevalence of the Confederate flag and 'Dixie' on campus. Harper said,

When I first got here, I didn't realize how big the flag and 'Dixie' was to this institution. And I got my first insight into that at the first football game that I went to. The cheerleaders would come out on the field first with this huge rebel flag, and then the Highty Tighties would come out playing 'Dixie.' When they played 'Dixie,' it was expected that people would stand, as if it were the national anthem.

I recall at a game I said, 'There's no way I'm standing for 'Dixie. And I remember someone punching me in the back at a football game and saying something to the effect about how I should stand. I looked at that person, and I said, 'You best not put your hands on me again.'

Scott was elected to the student senate, which proposed a resolution to stop the flying of the Confederate flag (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackwomen/scott2.htm). She said that she and others favoring the resolution received hate mail and ugly telephone calls. She recalled a demonstration on campus in which students flew their Confederate flags outside of their windows:

They would open the windows and hang their flags, and so the school was covered in Confederate flags at one point. And they would have the windows opened so that they could blast their records of 'Dixie' out of the window.

I had a Nina Simone record that had a lot of like protest kind of songs on it. One of them was called 'Mississippi, God Damn.' So I'd open my window and play my 'Mississippi, God Damn,' which was a wonderful protest. I still have that record. I used to also play it for parents when they came on Sunday for those girls who wouldn't speak to me. There was that subtle kind of stuff with the girls, and so that was my way of introducing their parents to the idea that there was a black girl on campus now, and you had to deal with her. I'd open my door and have my 'Mississippi, God Damn' playing out there until my roommate would come and say, 'Come on, now, give them a break.' Talk me into cutting it down a little bit. That was my way of dealing with it.

I just remember that we did it right. We didn't climb up the wall and pull it down or burn the building down. Remember this is also in the sixties in which that was definitely happening around the country. Kids were taking over buildings. They were a lot more militant than anybody at Virginia Tech. We were mild, very mild. I think that the University Council…. was wise in their decision because we could've become that.

Scott said she had to have a facade at that point:

It was like an evolvement. At first when I came here, I was a sweet child. By the time I left, I was Umgowa black power kind of person. I had become that, and I remember always having to have this serious facade so that people would take me seriously. So that they would be careful of what they would say around me. I guess in a way, I tried to become intimidating to people which I guess was kind of like a defense mechanism to surviving in this environment. Although I still like Betsy - the [white] girl who was my roommate. She was white, and we got along famously.

The Student Senate authored resolutions in the early 1970s to end the display of the Confederate flag and the singing of 'Dixie' at sporting events, but a football coach actually put at end to these practices because they were hurting recruitment of black athletes.

When Martin Luther King died, Linda Edmonds wrote a poem expressing her feelings, Thoughts on the Death of Martin Luther King (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/ blackwomen/king.htm). The site also includes an article from the student newspaper about a peaceful campus demonstration involving lowering the flag to honor Reverend King (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackwomen/flag.htm).

The Black Women's History Project Web site also includes full text of oral history interviews with Cheryl Butler, the first black woman in the Corps of Cadets (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/ blackwomen/cheryl/). Butler was a member of the original L Squadron, the first group of women to enter the Corps of Cadets at Virginia Tech. (When these women joined the Corps in 1973, they had to figure out not only how they would function as a squadron of females integrating the all-male Corps, but also what they would wear as a uniform. The mini-skirts they originally wore have since been replaced by garb identical to that of male cadets (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/125th/cadets/women/ldocs.htm).

Fig. 3: The Home Page for “Women in the Corps of Cadets” http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/125th/cadets/women/first.htm

Butler assumed a leadership position in the Corps her second year (1974-75) as squadron commander, and her concerns are more over issues of gender than of race. Viewers may learn more about the women in the Corps of Cadets and view images from a scrapbook of one of the original members of the L Squadron (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/125th/ cadets/women/lsquad/lsquad.htm).

The Black Women's exhibition also includes an oral history interview with and images of Marva Felder, who was crowned as Virginia Tech's first black homecoming queen in 1982 (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackwomen/marva/). The Picture Gallery features the moment when Felder learned she was homecoming queen (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackwomen/marva/table.htm). Felder said she did not expect to be chosen queen and was daydreaming when her name was announced. Her date, William R. Billups (class of 1984) had to nudge her to let her know that she was queen.

Finally, the Black Women's site includes an interview with Elaine Carter, who was a particularly appropriate catalyst for the project because her own background was inextricably linked with the black history of the New River Valley, the area in southwest Virginia where Virginia Tech is located (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackwomen/carter/). Born in Roanoke, she grew up in the rural town of Elliston in Montgomery County, about eleven miles west of Blacksburg, site of Virginia Tech. Her father was a bellman at the Patrick Henry Hotel in Roanoke. Her mother taught in an all black one-room school in Elliston until she integrated the teaching staff of Christiansburg Elementary School in 1964. Carter's paternal grandparents had been enslaved in Elliston. Her maternal great grandmother was a slave and, as the child of the slave master, had been brutalized by the mistress of the house.

The Web exhibit not only increased accessibility to project findings but also propelled the project in new directions and attracted new collaborators. Site materials were used in multi-media presentations, slide shows, permanent installations, articles, exhibitions, and as part of the curriculum. A faculty member from the Center for Interdisciplinary Programs produced a video about the first black women students, Legacies of Resistance and Survival: The First Black Women Students at Virginia Tech, to make materials easily accessible for classroom use. In addition, the existence of the virtual exhibition spurred the demand for a site that would include men as well as women.

The Men Need Something Too

The Black Women's History Project was launched on the Internet around the time of the 1995 Million-Man March on Washington. A male staff worker from the university's Black Cultural Center commented, 'The men need something too.' To give the interviews a chronological context and to broaden the project to include men as well as women, the Timeline of Black History at Virginia Tech was developed by the University Archives. The Timeline provided a framework from which links could be made to other documentation, images, articles, and oral history interviews. The Timeline includes student, faculty, and staff 'firsts' as well as significant happenings in the community. For example, there is an oral history interview with Rev. Phillip Harmon Price, who with his sister Ana was the first black student to integrate the local Blacksburg High School in 1961. The 1950s section contains a 1991 interview with Ellison A. Smyth, church pastor for 21 years, about the desegregation of the Blacksburg Presbyterian Church.

Fig. 4: The Home Page for the Timeline of Black History at Virginia Tech http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackhistory/timeline/

The Timeline includes materials about the Magnificent Eight, the first black male students at Virginia Tech, including an interview with Dr. Charlie Yates, the first black graduate of the university. (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackhistory/oralhistory/Yates/) The request for images from Lindsay Cherry, one of the first four black students to enter Virginia Tech (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackhistory/oralhistory/cherry/), sparked the interest of his daughter, a television producer. She used the images in a professional television spot for WVEC-TV in Norfolk for Black History Month (February 1998): Profiles in Courage: Dr. Charlie Yates. The short video (available through the Timeline home page) features Yates, Cherry, and Matthew Winston, three of the first black male students at Virginia Tech.

When Irving Linwood Peddrew III enrolled at VPI in 1953, he was not only the first black student at VPI but also the first black student in a four-year, public institution in any of the 11 states of the former Confederacy (Wallenstein, 1999). In March 2004, a residence hall was named Peddrew-Yates Hall in honor of Peddrew and Yates. There was irony in the building dedication as neither Peddrew nor Yates was permitted to live on campus in the dorms or to eat with fellow students. In an oral history interview, Peddrew recalled his isolation as a student. He said he very much wanted to go to the Ring Dance 'not to encounter a lot of ugliness, but I was prepared for it because I thought that I had the inner fire to exist and to persevere.' Rumors were circulated that the local girls' schools - Longwood and Radford –'wouldn't allow their girls to attend if I attended the Ring Dance, which was the biggest social event of a cadet's education.' Although the rumors proved to be unfounded, Peddrew decided not to go and published a letter in the 1956 Virginia Tech about his decision (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackhistory/timeline/peddrew_letter1.htm).

The following year the class officers invited the black students to attend the ring dance. Yates said, 'I felt good about that. Not because I felt it was so personal toward me - because it was progress that the students had made in one year.' However, Yates and Lindsay Cherry were called to President Newman's office and told he did not wish them to attend the ring dance. Newman cited the Board of Visitors' policy as the reason why they could not attend. The students assumed that if they flaunted that policy, they might be expelled. Yates said, “

I think the concern of the administration at that point in time was to bring as little publicity to the fact that black students were coming here as possible because in that way it was probably easier for Tech to go to Richmond to get some funds.

In addition to telling the stories of pioneering black students and recognizing the achievements of individuals, the Timeline highlights the development of significant organizations and centers such as the Human Relations Council, the Black Student Alliance, the Black Organizations Council, the Black Faculty/Staff Caucus, the Engineering Minority Center, and the Black Cultural Center.

Faculty, administrators, students, staff, and alumni responded enthusiastically to the Timeline. Comments ranged from a pleased: 'You got me when I still had hair!' to 'At last I can put my mouth around the words, 'I'm proud to be a Hokie.' (Hokie is a nickname for Virginia Tech students and athletic teams.) Faculty, staff, and alumni showed a sense of ownership for the site as they contributed items and images for inclusion. Several other universities and colleges have expressed interest in developing their own black history timelines. The Timeline served as a model for the recently launched Documenting the African-American Experience at the University of Mississippi http://www.olemiss.edu/depts/afro_am/African_American_Presence/

In the spring of 2000, Dr. Jim Watkins, spokesman for the black alumni of the 1970s, contacted the University Archives. He said, 'We may not be the first, but we have a story to tell too' About fifteen alumni came to an informal reunion on campus to discuss their history, and an oral history interview was conducted with Dr. James Watkins: http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackhistory/oralhistory/watkins/

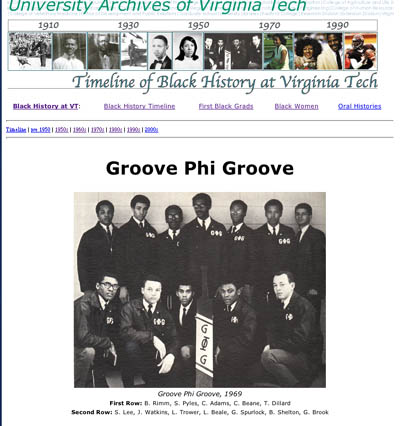

The 1970s alumni spoke of the cultural shock of coming to a campus where the Confederate flag hung in the Cassell Coliseum and was waved at football games and where 'Dixie' frequently was played by the Highty-Tighties, the Corps of Cadets' Band Company. Black students felt excluded from much of campus life, and all the black males were considering transferring out of Virginia Tech. Instead they organized the social fraternity, Groove Phi Groove. This fraternity allowed students to reinvent a familiar black community on campus and make a kind of home away from home where they could find companionship and a sense of identity. http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackhistory/timeline/gphig.htm.

Fig. 5: Groove Phi Groove, 1969

The small gathering of 1970s alumni resulted in a $25,000 endowed scholarship. The alumni request for a listing of the first 100 black graduates led to the development of The First Black Graduates of Virginia Tech (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/blackhistory/grads/). This exhibition uses a yearbook format to highlight the first 100+ black graduates at the university; it serves as another bridge to the past and a gateway to present involvement of alumni with the university. Another outcome from the alumni meeting was that the Office of Multicultural Affairs funded a graduate research assistant to help the University Archives document diversity. With this support, the project's scope was expanded to collect oral histories, images, and documentation that reflect the experience of current African American, American Indian, Southeast Asian, and Islamic students. Construction was begun on Cultural Diversity at Virginia Tech, which includes a section highlighting the First International Students by year and by country.

Fig. 6: The Home Page for Cultural Diversity @ Virginia Tech http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/diversity/

Collaborations with Faculty and Academic Departments

Biochemistry

The use of oral histories in on-line exhibits like the Timeline inspired the Department of Biochemistry to launch an oral history project as part of the celebration of its 50-year anniversary. Biochemistry faculty conducted oral history interviews about the development of the department. The 50-Year Celebration of the Department of Biochemistry (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/depthistory/biochem/) offers full text of the interviews, with sound clips, images, and other documentation. It also documents department head Kendall King's work with the Mothercraft Centers in Haiti (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/depthistory/biochem/king/). Mothercraft or Nutritional Rehabilitation Centers aim to educate mothers about how to feed and care for infants and young children using techniques compatible with their understanding and financial limitations. In developing countries, pre-school children are most vulnerable to restrictions in the food supply and, therefore, the group in which malnutrition is most serious. The importance of this work to children is brought home through images from the Mothercraft Center in Haiti (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/archives/depthistory/biochem/king/haiti1.html).

Theatre

Several virtual exhibitions were designed in collaboration with faculty for use in instruction. The Lyric Theatre: A Look Back at the Beginnings (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/specgen/lyr/lyrhp.htm) was designed with faculty from the Department of Housing, Interior Design and Resources Management to explore the history, design, and construction of a Blacksburg theater. The site makes available architectural drawings and sketches, including design alternatives; images of previous homes of the Lyric Theatre; programs; and other primary source materials such as budgets and information about the architects. It was unveiled as a companion to a gallery exhibition of construction drawings for the Lyric. While the physical exhibition was up for only a week, the virtual exhibit is always available to students and other users.

The Bank of Blackburg

Another collaborative exhibition for instruction, Reinventing the National Bank of Blacksburg (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/exhibits/bankofblacksburg/) revolved around a senior studio project to redesign the interior of the Bank of Blacksburg while maintaining the building's exterior structural integrity. Again, the Web site offered drawings and source materials. Both virtual exhibitions highlighted materials from the Smithey & Boynton collection, housed in Special Collections. The Bank of Blacksburg had an interactive component in that students put their designs on-line, and then mentors, who were VT alumni active in the field, critiqued their work, and made their critiques electronically available. The interactive features were available only during the actual course.

Time Past, Time Present--Time Travels through the Web

The Digital Library and Archives' Web pages offer a variety of exhibitions that let users enter other eras and see the world from different perspectives. Viewers can travel in time to see the Civil War from the perspective of a young drummer boy who is overwhelmed by homesickness, or view a virtual slide tour of the Blacksburg historic district and see what a Blacksburg woman at the end of the nineteenth century viewed as 'curious things.' Or the user can take a literary journey in celebration of Bloomsday, the day honoring James Joyce's Ulysses.

Blacksburg Bicentennial

Blacksburg's Bicentennial, 1798-1998, was developed to celebrate the town's 200th birthday. The exhibition includes timelines, documents, town views, maps, archaeological materials, and full text of A Special Place for 200 Years: A History of Blacksburg (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/bicent/recoll/histbook/specplac.htm). Another feature of this exhibition is the virtual slideshow 'Historic Architecture of the Blacksburg Historic District' prepared by architect Gibson Worsham (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/bicent/slides/ssintro.htm). The slideshow is based on a survey of the central commercial and residential portion of the Town of Blacksburg, conducted for the town and its Architectural Review Board. The survey was intended to complete the inventory and evaluation of the above-ground architectural resources in the district and to provide local government and other planning agencies with information that may be used to support the successful development of local preservation planning tools such as design guidelines, historic overlay zoning, and design review. The slide show concentrates chiefly on the newly surveyed properties in the district, but includes some photographs of other important structures.

Fig. 7: The Home Page for Blacksburg's Bicentennial, 1798-1998 http://spec.lib.vt.edu/bicent/

Another component of the Blacksburg's Bicentennial is the Diary of Rosanna Croy Dawson, which allows the user to experience life from the perspective of a woman of the 1890s (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/bicent/recoll/croy/croy.htm). Roseanna Croy Dawson (1822-1906) wrote her diaries in pencil in a small composition book using few capitals and practically no punctuation. D. Pack, compiler of the diaries, notes,

Her spelling is sometimes wrong, but then sometimes she spells everything right, so you can see she was just jotting things down without thought of someone copying it in the future.

Pack said that Dawson's diaries were written for her children: 'She jotted down the weather; people who visited for sewing by her daughter, Ella; happenings in Blacksburg.' The diary entries, such as her 1898 'A Sheat for Axidents an Curious Things' give a fascinating perspective of daily life in Blacksburg (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/bicent/recoll/croy/axidents.htm).

Civil War

The harshness of the American Civil War is brought home through The Letters of Felix Voltz, a drummer boy in the 187th New York Volunteer Regiment during the Civil War (http://spec.lib.vt.edu/voltz/voltz1.htm). Voltz enlisted in the army after an altercation with his older brother who gave him a blowing because he was slow getting ready for church. The letters poignantly reveal the plight of a very young, ordinary soldier who endures homesickness, hunger, filthy conditions, lice, and being 'sun struck.' Voltz asks his brothers to ask his father's forgiveness for being ugly and tell him 'that I have found out what A home is.'

Fig. 8: The Home Page for The Letters of Felix Voltz http://spec.lib.vt.edu/voltz/voltz1.htm

Celebrating Bloomsday

T.E. Kennelly's A Gallery of Bloomsday Cards celebrates Bloomsday, June 16, 1904, the date on which James Joyce's Ulysses takes place. Ulysses is loosely modeled on Homer's Odyssey, with Leopold Bloom a modern Odysseus or Ulysses in Dublin; Stephen Daedalus, Bloom's spiritual son, as Telemachus; Molly Bloom as Penelope; and Blazes Boylan, a suitor of Molly. Bloomsday also is the anniversary of the date of Joyce's first walk with Nora Barnacle, the woman who would become his wife.

Fig. 9: The Home Page for A Gallery of Bloomsday Cards http://spec.lib.vt.edu/specgen/blooms/bloom.htm (Reproduced with permission)

Kennelly's handmade postal cards juxtapose contemporary images of Dublin and the environs with text from Ulysses. Citations are deliberately omitted from the cards to set a kind of puzzle for the viewer. The 1985 card shows the Martello tower at Sandycove where Joyce himself lived for a brief time with Oliver St. John Gogarty and Samuel Chenevix Trench. Ulysses begins in the Martello Tower with 'stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed.' The 1984 card shows Bachelor's walk, Dublin, which Blazes Boylan passed on his way to Molly: 'By Bachelor's Walk jog jaunty jingled Blazes Boylan, bachelor, in sun, in heat, mare's glossy rump atrot, with flick of whip on bouncing tyres…' The historic Chapter House of St. Mary's Abbey is the subject of the 1991 card: 'Yes sir, Ned Lambert said heartily. We are standing in the historic council chambers of Saint Mary's Abbey where silken Thomas proclaimed himself a rebel in 1534. This is the most historic spot in all Dublin.' The 1999 card captures an image of the door, now demolished, at No. 52 Clanbrassil Street Lower, Dublin, which was the mythical birthplace of Leopold Bloom. Joyceans from Brazil to Australia to Dublin have responded to the virtual gallery of Bloomsday cards.

Building Blocks

A visit to the University Libraries' Digital Library and Archives would not be complete without exploring the VT ImageBase, which contains over 40,000 images (http://imagebase.lib.vt.edu/). The images reflect some of Special Collections strengths, such as the over 8,000 images of the Norfolk and Western Historical Photograph Collection (http://imagebase.lib.vt.edu/browse.php?folio_ID=/ns). The Civil War collection is represented the George F. Doyle and the H. E. Valentine Scrapbooks as well as images and full text of many other primary source materials. Compiled by a Charleston, Massachusetts, resident, the Doyle scrapbook contains Union song sheets, mourning cards, patriotic covers, and cartoons. The Valentine scrapbook contains random notes from the Civil War from diary and letters and ink washes sketched by the author around 1863-1864 of Virginia batteries, breastworks, sharpshooters, and other military sites. Another highlight of the ImageBase is the Palmer Collection with 642 images of Appalachian photographer Earl Palmer. The ImageBase also offers over 5,000 Virginia Agricultural Extension images and thousands of Virginia Tech images. It is a searchable database that offers a diverse variety of images that can be used for research and instruction or as the building blocks to create new virtual and gallery exhibitions.

References

Anderson, M. L. & P. Hill Collins, (Eds.) (1995). Race, class, and gender: an anthology. New York: Wadsworth.

Portelli, A. (1998). The Battle of Valle Giulia: oral history and the art of dialogue. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Wallenstein, P. (1999). Black southerners and non-black universities: desegregating higher education, 1935-1967. History of Higher Education Annual 19, 121-148.