|

|

|

|

Archives & Museum Informatics info @ archimuse.com www.archimuse.com |

|

Curating (on) the WebSteve Dietz, Director of New Media Initiatives, Walker Art Center1. Museums in an Interface CultureMuseums once thought of themselves as institutions to collect and preserve objects from around the world, places for scientific study of their collections, and only lastly as places to display the exotic to the public. Some have referred to this period of display as the stack 'em deep, pile 'em high philosophy of display. Over the years museums have changed a great deal. Today, while museums are diverse, as are their aims, it can safely be said that they are primarily in the business of dissemination of information rather than artifacts. The advantage to thinking in terms of information is that it validates the collection of intangibles, such as oral histories, and replicas, as well as actual artifacts; it places museums in a key position in an information age; and it makes it easier to integrate traditional functions of collection, preservation, research and display with the new watchwords, education and communication. Writing in 1992 about technology in museums, Bearman neatly

summarizes a profound shift in museums' perception of their mission,

which has only accelerated since then with the explosion of the

Internet and the World Wide Web . This shift has inevitably

placed stress on the curator's central role in the museum. Not that

they weren't already under fire on many fronts, from issues of omniscient

authority in a postmodern age of multiple meanings to accusations

of parsimonious gatekeeping to the challenges of communicating difficult

ideas and complex research to a "general audience" (which

usually means a lot of very different audiences with specific needs

and often-entrenched points of view). Regardless of how the curatorial

role is defined, however, the Net in particular and interface culture

in general introduce interesting and perhaps profound opportunities,

which might also be perceived as competitive pressures in the culture

arena. (2) My experience these days (as opposed to just last year) working

with museums and new media is that while most personnel don't understand

how the Internet works--which seems perfectly reasonable--increasingly

they understand how it can work for them. Usually this is

as another avenue for education and communication. In this sense,

there is nothing particularly revolutionary about the Web. It's

a bit like direct marketing, only funner. It's like distance learning,

only via a computer instead of a camera. It's like publishing a

brochure or catalog, only you can still make changes after it's

"printed." The echo of McLuhan here--we tend to understand

new media, initially, in terms of our understanding of old media--is

familiar and entirely appropriate. I am interested in at least considering whether and how digital culture may affect museum culture in unexpected--and perhaps "unreasonable"--ways. Steven Johnson writes toward the end of Interface Culture: The most profound change ushered in by the digital revolution will not involve bells and whistles or new programming tricks. . . . The most profound change will lie with our generic expectations about the interface itself. We will come to think of interface design as a kind of art form--perhaps the art form of the next century. And with that broader shift will come hundreds of corollary effects, effects that trickle down into a broad cross section of everyday life, altering our storytelling appetites, our sense of physical space, our taste in music, the design of our cities [emphasis added]. (3) I am skeptical of interface becoming the new art form for a century, but I do find plausible that our understanding of interface will expand dramatically and impact directly on creative expression, which is why, in this paper I look primarily, although not exclusively, at examples of the intersection of museums with the Web in the arts. I believe that contemporary artists and "interfacers" (Johnson) have much to teach us about the relevant possibilities of a new medium in a changing society.

|

|

2. Museums Respond to the WebVirtual Tours & Augmented Museum Exhibitions Skipping right over the "brochure-ware" era of museum

Web sites, museums quickly realized the possibility of putting their

exhibitions online, often augmenting the efforts with richer information

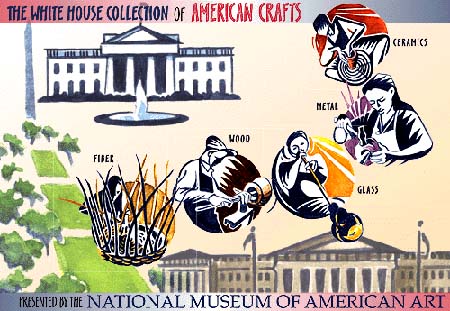

that might not be available at the exhibition. For instance, the Smithsonian's first online exhibition

was "The White House Collection of American

Crafts," presented and produced by the National Museum

of American Art. This exhibition included extensive video and audio

clips of the curator talking about selected pieces and handling

them in ways that would not be possible during the exhibition. In

addition, each artist was asked to answer a series of questions

about their work, which was not part of the exhibition itself.(4)

You Are There: The Immersive Interface

Another approach besides exhibition "augmentation" that

museums have attempted on the Web is a "you-are-there,"

more immersive interface using QTVR (e.g. Walker Art Center's Andersen

Window Gallery), RealSpace (e.g. National Gallery of Art's

Thomas Moran or VRML (e.g. The Natural

History Museum's The Virtual Endeavour).

Interestingly, there is some preliminary evidence from the Virtual

Endeavour experiment that younger visitors prefer the greater interactivity

and control of navigation allowed by an immersive interface. (5)

If this proves true, it may become a significant reason for museums

to experiment with innovative interfaces. Currently, such efforts

are often considered simply "bells and whistles," which,

if anything, complicate rather than enhance communication. The Extended ExhibitionFinally, in terms of online tours of museum exhibitions, besides augmenting the exhibition and presenting an immersive interface, there is also the option of extending the exhibition. Like the best exhibition publications, extending an exhibition online means more than simply re-presenting it but also reformatting it for the best possible experience in the medium--in front of a computer screen, transmitted via the Internet. One example of extending the exhibition is Diana

Thater: Orchids in the Land of Technology. The online version

was "announced" by an automated series of pages, which reprised

one of Thater's video works, which appeared as a "tunnel"

to the entrance to the Walker home page.(7)

Clicking on it dumped the viewer in front of a scrolling quote by

Walter Benjamin, which was also based on a "wall label"

displayed on a TV monitor at the beginning of the site-exhibition.

The viewer can then "wander" through QTVR galleries, where

many of the depicted objects are "hot." While wandering, it is possible

to listen to audio snippets taken from an opening day dialogue with

the artist. But it is here that the designer, Louis Mazza, extends

the experience by re-mixing the audio in a way that calls attention

to the mix, just as Thater's "mixing" of the rgb channels

of the video projector calls attention to the technological and constructed

underpinnings of the normally transparent, narrative experience. It's

a fine line between presenting the work in an exhibition and extending

it appropriately--appropriate to both the work and the medium.

One example of extending the exhibition is Diana

Thater: Orchids in the Land of Technology. The online version

was "announced" by an automated series of pages, which reprised

one of Thater's video works, which appeared as a "tunnel"

to the entrance to the Walker home page.(7)

Clicking on it dumped the viewer in front of a scrolling quote by

Walter Benjamin, which was also based on a "wall label"

displayed on a TV monitor at the beginning of the site-exhibition.

The viewer can then "wander" through QTVR galleries, where

many of the depicted objects are "hot." While wandering, it is possible

to listen to audio snippets taken from an opening day dialogue with

the artist. But it is here that the designer, Louis Mazza, extends

the experience by re-mixing the audio in a way that calls attention

to the mix, just as Thater's "mixing" of the rgb channels

of the video projector calls attention to the technological and constructed

underpinnings of the normally transparent, narrative experience. It's

a fine line between presenting the work in an exhibition and extending

it appropriately--appropriate to both the work and the medium.

Exhibitions Designed to be OnlineIncreasingly, exhibitions are designed to be at least partially online. That is, from the earliest conception for an exhibition, an integrated online component is planned. Primarily, these involve site-based exhibitions, but this is also changing, as we shall see. Just a few examples include: Arts As Signal: Inside the Loop, Bodies Incorporated, Mixing Messages: Graphic Design in Contemporary Culture, and Techno Seduction. One of the most radical online exhibitions is the Smithsonian's Revealing Things curated by Judy Gradwahl. Based on "everyday objects" in the collection of the National Museum of Natural History, there is no physical installation related to this effort, on which Gradwahl devoted over two years. It is not clear whether in the long run, entirely virtual exhibitions of physical objects will become a common practice--some would say that the authentic object is just about the only thing separating museums from all other online curatorial practices--but regardless, it is an important benchmark. The site also uses an innovative interface based on Plumb Design's Thinkmap.

The Curator As FilterNo matter which way you slice it, of course, putting some version of an exhibition online is not the same as curating on the Web. Here museums to date have been more circumspect, but there are several fruitful directions that have been tried. At the present time, the museum community is expending a great deal of effort simply digitizing its resources and making them increasingly accessible online. Digitizing assets is not dissimilar to the historical function of the museum to preserve artifacts. As this process becomes more and more successful, however, there will be an increasing need to find ways to "filter" the vast quantities of information that are available. The emphasis will shift from simply "creating" content to presenting a context for it; a point of view about it--just as one of the roles of the curator is to identify, contextualize, and present a point of view about works of art. While lots of museum Web sites have lists of links, few tend to "curate" these links or offer much reason for listing them beyond a generic "sites to check out." The Whitney Web site, for instance, states, "From this location, we offer a link to other museum sites, where some of the most interesting online delivery of museum content is occurring. Inclusion in this list does not constitute an endorsement by the Whitney Museum, nor is this list by any means comprehensive." And while this may be more explicit than most, it is not uncommon. The Musee d'art contemporain de Montreal has one of the most organized and comprehensive listings of contemporary art on the Web, but they too don't provide much contextualization for the links. The Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center states, "We're interested in exploring the Web as a "new medium" for artists and are planning to develop this Virtual Exhibitions page to do just that. In the interim, here are links to various sites that use cyberspace as art space." And they do provide contextual information about the links. Interestingly, a science museum, the Exploratorium, lists a weekly "ten cool sites," many of which are often art sites. The National Museum of American Art's photography online site, Helios, also reviews photography web resources every two weeks in "Transmissions."

Curating the Web: Maps & HyperessaysThe closest parallel to a "curated" list of Web links may be the annotated bibliography. Once, however, we delve outside of the museum's collection (on the Web), even in a bibliographic way, the conceptual floodgates open to curating the Web itself, so to speak. Of course, exhibitions from outside the collection are nothing new, but it is still not widely practiced on the Net. There are, however, some intriguing examples. The Institute for Contemporary Art in London has what it calls "Curatours," which "explore ideas and themes across web sites. Each Curatour explores a different theme and is curated by a specialist within the field." To date there are only two curatours and they are approaching a year old, so it is not clear whether ICA intends to continue the program. Artist Jake Tilson's Colour-Color "focuses upon the use of colour on the Internet from symbolism and theoretical issues to the effects it creates." The other curatour, Collapse is actually less a Web tour than the idea of using a different interface--in this case VRML--to explore the ICA Web site from a different vantage point, so to speak. a concerted effort to chart this terra incognita [of cyberspace]. The aim of CyberAtlas is to commission and collect a series of maps of cyberspace, with a particular focus on sites related to visual art and culture. Unlike the typical navigational chart, the maps in CyberAtlas can take you where you want to go as well as tell you how to get there: clicking on a Web site in any of the maps will transport you immediately to the corresponding page on the Internet."Its first two projects are Electric Sky by Jon Ippolito--"Bright stars in the firmament of online art and the networks that support them--and Intelligent Life by Laura Trippi--"A thematic map that traces connections between recent scientific developments and art, theory, and popular culture." These are wonderful, must-see works, which point to an important direction in curating (on) the Web. As a variant of the Web map, the Walker Art Center commissioned a "hyperessay" based on the life and work of Joseph Beuys. The occasion was an exhibition of his work, but the goal was to write an informational text that could not only be read in a non-linear manner, but would also be designed to take advantage of the vast resources of the Internet by linking out to them whenever appropriate. If the World Wide Web is a prototype of Bush's Memex or Nelson's Xanadu, then we should be able to construct programming that takes advantage of this "universal library." (8) The Walker plans to commission at least three hyperessays a year on broad themes that relate to on-site programming.

Curating Web ArtAnnotating links, mapping territory, navigating a route, are all curatorial-like functions operating on digital objects and/or in a digital domain. Perhaps the clearest expression of this kind of effort is curating Web-specific art. While technology, including the Web, has been making its way into the gallery for the past 30 years or more, there appears to be little consensus in the museum community about the definition or even the value of Web-specific art. Many artists have incorporated the Internet as an aspect of their physical installations in museums: Shu Lea Cheang's Bowling Alley originally presented at the Walker Art Center, Peter Halley's recent installation and Exploding Cell project at the Museum of Modern Art, to name just two, but museums' embrace of Web-specific art has been more cautious to date. Two of the earliest pioneers, it is interesting to note, are both university museums with a strong connection to photography and to artist-run programming. The California Museum of Photography at UC Riverside has been presenting Web-specific artist projects as well as encouraging installation exhibitions that have significant Web components for several years. They even acquired a copy of the software program Adobe Photoshop for their permanent collection because of its importance to the future history of imaging. @art, one of whose founders, Joseph Squier, is a photographer, is an electronic art gallery affiliated with the School of Art and Design, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. @art's projects include works by Peter Campus, Carol Flax, Barbara DeGenevieve, and others. One of the most innovative and substantial efforts by a museum to support Web-specific art is Dia Center's series of over half a dozen projects since 1994. Here is a self-description of their efforts.

Collecting Web ArtThe San Francisco Museum of Modern Art made one of the biggest splashes to date in terms of museums and the Web by "acquiring" portions of three Web sites: adaweb, Atlas, and Funnel. Even though curator of architecture and design, Aaron Betsky, asked these Web sites to make a donation to the collection, and he "is treating the pieces as he would graphic design, rather than works of fine art,"(10) the conscious, curatorial decision to collect "this over that"--especially when "this" is a Web site--is a significant event. The Whitney Museum of American Art acquired Douglas Davis's The World's First Collaborative Sentence as part of the estate bequest of collector Eugene Schwartz and has plans to host it from their server, although it is still hosted by the university department where it began. Walker Art Center also has an agreement in principle to acquire the complete adaweb Web site, which its corporate owners are no longer willing to support as an ongoing effort.(11) adaweb would continue to be served from the Walker site but new projects would not be added to it. The Walker plans the acquisition of adaweb as a significant first step in an ongoing commitment to create a digital study collection of Web-specific art.

3. Cultural CompetitionWhen Disney proposed a historic theme park partially on the site of a Civil War battlefield in Virginia, there was much hue and cry--and only part of it came from the nearby landed gentry concerned about its impact on their fox hunting. There was equal concern about the "Disneyfication" of history and how could a real museum like the nearby Smithsonian compete with such "edutainment." In fact, it is commonplace to bemoan the task of museums who must compete with the various juggernauts of popular entertainment, whether they be Niketown or Disney or Amistad. Without downplaying--or wanting to get into, here--issues of authentic and inauthentic experiences in a mediated culture, from my perspective, forget competing with the artistic vision of a Steven Spielberg or James Cameron, we museums are hardly keeping in sight of let alone abreast of the more modest efforts of artists and artist organizations working the Web today. In January of 1997 I was asked by the AAM publication, Museum News, to write about the best museum Web sites. I ended up suggesting that a non-museum, artnetweb, had the best museum Web site. The museum Web environment is an order of magnitude richer a year later, but I'm still not convinced that the best museum Web sites are being produced by brick-and-mortar museums with collections of artworks. Virtual MuseumsJust as in "real life," where the Louvre is one of the most renowned museums in the world, Le WebLouvre is one of the best known, most visited, and most often linked Web sites in cyberspace. Only Le WebLouvre is a virtual museum. It has no collection and is not officially related to the Louvre (it is now formally called Le WebMuseum after a "conversation" with the Louvre's lawyers). Part of the ENST (Ecole Nationale Superieure des Telecommunications, Paris) World Wide Web server, Le WebLouvre - no official relation to the famous art museum - was created by Nicolas Pioch, a 23-year-old student and computer science instructor at the ENST. The project is continually being developed and expanded with the help of outside contributors because "more artistic stuff is needed on the Internet," as Pioch explains.(12) There are other examples of virtual museums that either "borrow" the collections of other museums or model themselves on a museum, but I am more interested in the incredibly wide range of "institutions" that do many of the things that museums should consider doing more of, without needing to define themselves qua museums. What is the point, after all, if the collection is either virtual (i.e. non-existent) or digital, in which case it is infinitely and exactly replicable and the issue of ownership is not as central as other kinds of issues, such as point of view, context, innovation, support of artistic practice, and much more? Virtual Arts Organizations

There are probably hundreds of virtual organizations even in the delimited realm of contemporary art. An inadequate list of some of the more outstanding would include: adaweb, Digital XXX, irational.org, Stadium, The Thing, Turbulence, Year Zero One, and ZoneZero. A list of the artists and projects represented by just these sites, however, would constitute a significant "collection." [Before you groan about all the great sites missing, read on, many more are discussed below in different contexts.] What's more, the commitment of each of these sites to a critical context, education, innovative interface, community building, and yes, curatorial selection, is impressive and inspiring. The interesting question is not how do these sites match up with museum sites or as virtual museums, but rather, what do traditional museums have that these sites don't or couldn't? Before exploring this question, however, I'd like to detail some of the other "competition" that museums face. In the "atomic world," it is difficult for an arts magazine, for instance, to compete directly with a museum. A "project" on the pages is seldom comparable to an installation in the galleries. In the digital realm, however, the virtual gallery of a zine is potentially just as effective as the virtual gallery of a museum--both can provide the same amount of hard drive space, of cyberspace, of color space, of coding capability. Again, so what is the difference? Zine GalleriesIt may be true that every graduate art department and 50% of the undergraduate departments around the world are starting online zines. And many of them are very good. Nor is academia the only source of zines. But wherever they come from, most that deal with art and visual culture in any significant way, "curate" digital galleries of online artworks. A short and again inadequate list might include Hotwired's rgb gallery, Leonardo Electronic Almanac, Speed, Switch from the CADRE Institute at San Jose State University, Talk Back!, Why Not Sneeze? and many others. As the programmer for Walker's Gallery 9, I could--and do--identify many of the same goals. How are we diferent? A Moveable FeastOne of the best known sites for new media did not even have a permanent public home until last year. However, Ars Electronica's "Festival of Art, Technology and Society" has been a significant force for almost 20 years and in recent years has had extensive Web presence. Similarly, the annunal conference for the International Society for Electronic Arts (ISEA) hosts a Web site with a juried set of links to artists' work. The venerable SIGGRAPH conference has an online art gallery. Even the most recent Documenta curated a Web site separate from its physical installations. And for this year's Museums and the Web conference, there is an online exhibition of net art.Some of the most significant effort in terms of identifying and contextualizing net art is being done on an annual basis at festivals and conferences around the world. And while a CU-SeeMe connection or http click may not be the same thing as sipping espresso at a sidewalk cafe in Paris, it is truly a networked feast that allows for some of the same "branding" advantages of sited museums.

Designing ArtIn the digital realm, it seems as if it is not enough for design studios to have a few prestigious accounts, such as museum Web sites. Many of the major agencies create their own "art" Web sites--semi-autonomous efforts that are seen as both a creative outlet and a kind of research effort for cutting edge design. For example, Agency.com has Urban Desires, a heretofore zine-format effort that is in the process of changing but whose goals are perhaps even more directly about creating cultural content: "...we will create a venue for the distribution of new-school new media: highly visual pieces, not so linear storytelling, interactive explorations, short films, animations, games, experiments, media hoaxes.... and who knows what else."(14). Razorfish has two efforts.The Blue Dot "curated" by Craig M. Kanarick, which takes as its challenge to "prove that the Web can be beautiful," and rsub, the goal of which is to "create an online network of original content just when everyone else has given up." Beyond the (con)fusion of design houses creating original content/art, the interface itself, as has been discussed, is an important art form (e.g. SFMOMA collecting Web site design). One particularly interesting interface, Plumb Design's Thinkmap/Visual Thesaurus, was actually a spin-off of Razorfish's rsub, and is the main interface for the Smithsonian exhibition, Revealing Things mentioned earlier. e-Commercial GalleriesCommercial galleries throughout the history of modern art have been among the most prescient in recognizing new art forms. Perhaps given the ease of replicability of much net art coupled with an anti "product" attitude on the part of many practising net artists, there still is not widespread activity on the net by commercial galleries, but some significant efforts do exist, such as the Sandra Gering Gallery, Postmasters. There are also other interesting outlets, such as the Robert J. Schiffler Foundation.

Libraries & ArchivesNormally, we think of libraries and archives as complements to museums, which they certainly are, of course (and vice versa). At the same time, to the extent that museums are "primarily in the business of dissemination of information," there is overlap. In the short run, librarians' efforts to identify quality sources of information should point them toward museum resources, if we do our jobs well.(15) In the long run, however, decisions about what "stuff" to archive--including, for example, art Web sites--is tantamount to a curatorial decision. Except not only might curators not be making these decisions, they may not be made directly by any human at all. In his fascinating paper for the Time & Bits conference, Michael Lesk debunks the notion that it will be physically impossible to store the sum of human knowledge but suggests an even greater problematic--how to evaluate it. There will be enough disk space and tape storage in the world to store everything people write, say, perform or photograph. For writing this is true already; for the others it is only a year or two away. Only a tiny fraction of this information has been professionally approved, and only a tiny fraction of it will be remembered by anyone. As noted before the storage media will outrun our ability to create things to put on them; and so after the year 2000 the average disk drive or communications link will contain machine-to-machine communication, not human-to-human. When we reach a world in which the average piece of information is never looked at by a human, we will need to know how to evaluate everything automatically to decide what should get the precious resource of human attention.(16)Standards, Dewey decimals, archives, longevity. These are not sexy topics, but unless we pay attention, history may end up being understood by our grandchildren in a much different way than we lived it.

4. Artists Show the WayArtists understand the network almost intuitively, have shown incredible interest and enthusiasm in the collaborative process, and exposed really interesting takes on what the Web can be used for, how it would change the way we communicate, how it would group people differently, creating what I sometimes refer to as a vigeo world--virtual geography, informed by media.--Benjamin Weil, curator, adaweb net.artNot only are many artists engaging the Web with innovative work, but some are also problematizing the potential role of museums and other institutional spaces/collections vis-a-vis the Web in challenging ways. The obvious issue that comes to mind is the Internet's "many-to-many" structure and what has been called "disintermediation." In other words, through the Internet, an artist almost anywhere in the world can reach anyone almost anywhere else who has an Internet connection. without having to go through the a "middleman," such as a gallery or museum. One of the better-known efforts in this regard--and more mysterious in many ways--is a loose confederation of artists, who sometimes admit to the rubric "net.art" and have congregated at various points around the discussion list nettime and the Web site irational.org as well as several others. Suffice it to say that the nettime archive and irational.org are worth spending a great deal of time reading and clicking through but that the artists and theorists associated with net.art self-consciously problematize issues of curation and institutionalization at the same time that they practice forms of it. Also when we talk about net.art and art on the net some people say that we should get rid of the very notion of art and that we have to do something that is not related to the art system, etc. I think it's not possible at all, especially on the net, because of the hyperlink system. Whatever you do it can be put into art context and can be linked to art institutions, sites related to art.--Alexeij Shulgin Netart functions only on the net and picks out the net or the "netmyth" as a theme. It often deals with structural concepts: A group or an individual designs a system that can be expanded by other people. Along with that is the idea that the collaboration of a number of people will become the condition for the development of an overall system.--Joachim Blank Shulgin's Desktip IS is symptomatic of this approach. Desktop IS is both a "work" by Shulgin and a group effort open to anyone. The "call" is worth quoting in its entirety. DESKTOP IS Our working method might best be described as painfully democratic, because so much of our process depends on the review, selection, and critical juxtaposition of innumerable cultural objects, adhering to a collective process is extremely time-consuming and difficult. However, the shared learning and ideas produce results that are often inaccessible to those who work alone. (18) The Internet, however, is perhaps a uniquely fluid and supportive medium for such projects--in terms of putting out the call, in terms of the ease of creating the work, in terms of contributing the work, and in especially in terms of displaying the work (despite the possibility of a gallery installation of Desktop IS, it lives perfectly comfortably on the Net). Perhaps most importantly, however, as the Net becomes increasingly ubiquitous, the designed interface becomes concomitantly central to our lives, and it is important to question and investigate it as something that is indeed constructed and not "natural," as we have come to unconsciously think of the desktop--if we think of it at all.

Collaborative ArtAntonio Muntadas's File Room installation was not intended as a Web-only project like Douglas Davis's The World's First Collaborative Sentence, but it was specifically extended to the Web in order to invoke the collaboration of people from around the world. The File Room ... documents numerous individual cases of censorship around the world and throughout history with an easy-to-use, interactive computer archive. ... The File Room acts not as an electronic encyclopedia but as a tool for information exchange, and a catalyst for dialogue. Texts and images have disappeared, been removed from view, or banned since the beginning of history. This project intends to make visible, world-wide, some of these incidents and acts as a source of documentation for new incidents which can be submitted by users on-line. File Room not only allows users to add their own stories to the files, but it also uses the searchable, random access capabilities of digital media to help make that which was invisible more easily visible. Although, as an ironic and tragic footnote, with the closing of Randolph Street Gallery, which co-produced the project, File Room is no currently longer available online in its most recent incarnation.(19) Audience As CuratorIf the popular refrain of visitors to exhibitions of abstract and other contemporary art is "my 6-year-old-niece could do that," the net equivalent may be a smart agent knowing before you do what book or music CD or artwork you are going to like and linking you to it. The artist team Komar and Melamid have taken this a step further by creating paintings based on "scientifically sampled" user preferences. This project, created by the dissident Russian artists Vitaly Komar and Alex Melamid, attempts to discover what a true "people's" art would look like. Through a professional marketing firm, a survey was conducted to determine what Americans prefer in a painting; the results were used to create the painting America's Most Wanted. This project was expanded in both scope and audience through the Internet at Dia's website, allowing visitors to see the paintings based on completed polls of over a dozen countries, analyze the survey data, and participate directly a website survey to create a new "Most Wanted" painting specific to the Internet community. While Komar and Melamid do not go so far as to "mass customize" their offerings--they are more interested in the mean and the norm--the aspect that taking their project to the Web clearly plays with is the much-vaunted two-way communication of the Net. Not only can viewers tell the artists what they think, they can even directly influence what they create. Paul Vanouse takes this a step further with his Persistent Data Confidante project. With PDC, visitors tell a secret (of at least 10 words) and then are told a secret, which they rate (Vanouse says cu-rate) on a scale of 1 to 10. Over time, as secrets receive more ratings, they are in turn algorithmically rated as to suitability for "reproduction". Eventually, the highest rated secrets mate and are fused to create a "new" secret. Curating as Darwinian selection? Participants get to chose/curate their favorites, yes, but the results of their choices are unknowable--in a not dissimilar way from not knowing how Komar & Melamid's paintings will ultimately turn out.

The Artist As MuseumFrom Andrew Wyeth to Any Warhol, it is nothing new to have a museum devoted to a single artist, even while the artist is alive. It is somewhat less usual for the artist to be architect, director, exhibit designer, publications and pr manager, registrar, educator, and, oh yes, the artist. But there are a number of such edifices on the Internet that playfully mimic the traditional structures of the museums in the zero g of cyberspace. The Lin Hsin Hsin Art Museum is perhaps the most energetic example around, complete with souvenir shop, cafe, a musical toilet, and much, much more. Become a member now! and received discounted admissions to . . . The Hsin Hsin Museum is a bit like the roasting of a famous person. One can speak the truth by clothing it in excess. Whether or not it is tongue-in-cheek, Hsin Hsin's museum skewers The Museum by so faithfully and lovingly recreating its forms without worrying too much about its meanings. And this is a not inaccurate description of the first couple of waves of museum Web sites. We knew the form, and we managed some jazzy technology, but is that the experience we want to have on the Web? Robbin Murphy's Project Tumbleweed, however, is a bit like visiting a large museum where lots is going on and the signage really only makes sense after you've been there a few times and are starting to become comfortable with things. To the first time visitor it can be a bit disorienting, but it's clear there's something there. Murphy, a co-founder of artnetweb (and it's not always clear where one stops and the other begins) writes of his project: The entire project is an evolving investigation into the possibilities of multi-dimensional on-line environments and will be one model for what many think of as a "virtual museum." I use this term with hesitation but acknowledge that it has become common to think of an online representation as something virtual, meaning unreal, and is a result of thinking in terms of multimedia CD-ROM and other forms of digital delivery that have become current but are not necessarily applicable to a networked environment like the Internet. Unlike Hsin Hsin, who touts "over 1000 digital artworks" like a Corbis press release, the artwork is a bit harder to find in Project Tumbleweed--or rather the project is the artwork, to a large degree. There is a collapse of container and contained. Everything is surface, no matter how deep you go. As Mark Taylor writes about another architect, Bernard Tschumi, in his brilliant new book, Hiding: When reality is screened, the real becomes virtual and the virtual becomes real. In his current work--especially the Columbia University Student Center--Tschumi extends the processes of mediaizing and virtualizing reality by transforming bodies into images. The in-between space where media events are staged is folded into the building in such a way that screens screen other screens. Infinite screens render the real imaginary and the images real.... Screens are not simply outer facades but are layered in such a way that the building becomes an intricate assemblage of superimposed surfaces. As bodies move across skins that run deep, the material becomes immaterial and the immaterial materializes. Along the endless boundary of the interface, nothing is hiding.(20)There are digital reproductions of earlier paintings by Murphy, for sure, but these really serve more as "stations" for him to meditate both on his life and the construction of meaning/the meaning of art. More critically than presenting some notion of his work per se, built into the structure of Project Tumbleweed are the notions of point of view and perspective. That is, Murphy acknowledges and plays out multiple roles--and assumes the visitor will also be coming from different points of view, whether as surfer or critic, artist or player, archaeologist or diviner. The main structural way this is accommodated is by three "levels" (perspectives): "<i> i o l a </i>" is the foreground (red) platform and is a personal curated interface with the rest of the Internet through links to articles, e-zines, books and projects updated on a daily basis. It is an "entrance" to the rest of the project yet most of the links will take a visitor elsewhere. Most institutions want to keep visitors within their own "space". What they don't take into consideration is that in the physical building people do not materialize in the doorway, they come through some mode of transportation -- walking, taxi, bus -- and from the "outside". The transition from "outside" to "inside" is metaphorical on-line and the advantage of linking would seem to be the ability to link in both directions. The advantage is that it creates a space of entering with the possibility of going elsewhere and that encourages return visits. The entrance has a use other than as an aesthetic decompression chamber. This is a significant project that museums would do well to steal as much as they can from. For a more traditional-seeming but thoroughly thought-provoking and engaging iteration of the "virtual museum," see ZoneZero: From Analog to Digital Photography. Pedro Meyer, the creator of ZoneZero, however, makes a strong and provocative case that the best way to think of ZoneZero and other similar sites is not as a virtual version of an analog medium we already think we know and understand but as a completely new form of art. See in particular his editorial, "Questions of what constitutes art on the Web." 5. net.curator?Guide On the SideIn education, it has become commonplace shorthand to describe the changing role of the teacher as going from the "sage on the stage" to the "guide on the side." Technology doesn't cause this, but it can abet it. With museums' focus on outreach, it may be that the role of the curator is undergoing a similar transformation. And to the extent that collaborative processes are desirable, the Internet is a great facilitator. I think the first time that I really woke to this possibility was stumbling across the listserv for the exhibition: PORT: Navigating Digital Culture. Basically, it was an open curatorial process that anyone could participate in, could propose projects for, could just listen in on. It would be naive to think that all decisions were made on that listserv, but basically it created a context for itself, both to test out ideas and to identify opportunities.(21) Auto-CurationThe Hsin Hsin Museum, Project Tumbleweed, and ZoneZero can all be viewed as examples of auto- or self-curation by artists, but there is also the idea of automatic curating. The most likely version of this in the near future--in the present, in fact--is of the "make your own map" variety. For instance, right now I can go to the Arts Wire Web base and put in criteria such as that I want to see Web-specific art on museum or gallery Web sites that have the word "women" in the site description. Voila. Instant tour of the Web. Of course, there are a number of factors affecting how well the territory is covered, so to speak. How often is the database updated? How consistently are criteria applied? How deep is the information catalogued? How well is the contextual web captured? How spunky is the algorithm...? It may not be the sexiest topic in the world, but databases like those used on the National Gallery of Art and San Francisco Museum of Fine Arts Web sites allow for very sophisticated interrogation of the museums' resources. There is no reason--in fact, every likelihood--that such cataloging will occur across the Web, across knowledge domains, across artifact types. With such Xanadu-like access to information, the value of the curatorial role will lie not so much in what is known as in how well the stories can be told. Storytelling doesn't have to be conflated with Disney and Hollywood. (22) There is an experimental "virtual curator" program called "The Intelligent Labelling Explorer." The focus of the project is automatic text generation. In this field, systems are built that produce descriptive, explanatory, or argumentative texts to accomplish various different communicative tasks. We plan to build a system that produces descriptions of objects encountered during a guided tour of a museum gallery. In the first instance, the tour will be of a `virtual' gallery, explored via a hypertext interface.(23) The computing challenge of ILEX is being able to generate text dynamically based on tracking what the user has already viewed and her level of interest. To create the text-base, the ILEX researchers spent many hours interviewing the curator of the collection being used (jewelry), parsing her knowledge into stories about the different objects, which she had told during guided tours. Interestingly, in February, Scientific American Frontiers aired a show in which "Alan 2.0"--a realistic digital recreation of Alda's likeness--was programmed to be able to speak lines he had never spoken before by accessing a database of phonemes he had spoken. Imagine marrying the dynamic text generation of ILEX with a realistic visual model that can speak the text believably.(24) Conversation with a virtual curator that does not have to follow a pre-defined script is no longer science fiction. The point of all this is not to hype some future of animatronic curators, who know everything but don't necessarily act like they do. But as society's ability to process "information" becomes ever more fluent, we may need to refine our notions of what the best roles of museums and curators are.

6. Hybridity and FusionReal virtual museums are already appearing on the horizon. Franklin Furnace, for instance, recently closed its doors and is now curating a bi-weekly performance series specifically for the Internet and planning to make its extensive archives available via the Web.By and large, however, a monolithic approach, whether toward exclusively utilizing or specifically ignoring the virtual, is unlikely to be a major trend. Instead of either/or, the answers will be both or neither--a third way. Museums such as ZKM are already making extensive efforts to integrate new media--all media--into their permanent collection dispaly on a permanent basis. Conversely, museums of contemporary art such as Chicago and San Diego, and the Walker Art Center (among many) are making significant efforts to take their programming online. Recently, this "in between" approach has been codified (at least version 1.0) in the Technorealism "manifesto." Neither savior nor antichrist, technology cannot give museums a purpose, but museums ignore the reality of the virtual at their peril. It is clear to me what innovative applications of the Net have to offer museums. What is less clear is whether museums will automatically "win" the cultural competition, if and when they jump into the fray wholeheartedly. There is evidence both ways. Only five years ago, you could not have had a more venerable brand than Encyclopedia Britanica. Yet, essentially, a $100 CD-ROM version of a defunct competitor, Funk & Wagnalls, bankrupted EB. We could argue till the cows come home over whether--or rather to what extent--this was a case of "the people" preferring cheapness over quality, or a triumph of marketing (shades of vhs vs. beta) or a dinosaur not paying attention to its future and feeling secure in a humungous set of door stops costing well over $1,000, as if the format was what was important, not the knowledge and information it contained (does IBM ring a bell?). So what does this have to do with museums? I think it is a cautionary tale that our existence may not be guaranteed, especially in an unchanging form, regardless of how impossible and even ridiculous it seems now to contemplate a universe without us. Prosperity, if not survival, may require an increasingly hybrid self-definition and an openess to fusion and mutation. As for curating, we have no choice. We will go where the artists

lead us. LinksWhite House Collection of American Craftshttp://nmaa-ryder.si.edu/whc/whcpretourintro.html "In virtu" tour (video clips) http://nmaa-ryder.si.edu/whc/invirtutourmainpage.html "Ask the artist" additional questions example http://nmaa-ryder.si.edu/whc/artistshtml/hoffmann.html Return to text. Alternating

Currents: American Art in the Age of Technology Andersen

Window Gallery, Walker Art Center National

Gallery of Art (DC) "Web Tours" using RealSpace

The

Natural History Museum (London), Virtual Endeavour Diana

Thater: Orchids in the Land of Technology Art

As Signal Whitney

Museum of American Art Art Links Musee

d'art contemporain de Montreal Cincinnati

Contemporary Arts Center Virtual Exhibition Links Exploratorium

Cool Art Sites Helios,

National Museum of American Art Curatours,

Institute for Contemporary Art (London) CyberAtlas,

Guggenheim Museum "Beuys/Logos:

A Hyperessay," Walker Art Center Shu

Lea Cheang, Bowling Alley Peter

Halley, Exploding Cell UCR/California

Museum of Photography @art

Dia

Center for the Arts Artists' Projects for the Web Walker

Art Center Gallery 9 San

Francisco Museum of Modern Art Web site Steve Dietz, "What

Becomes a Museum Web?" Le WebLouvre adaweb

Leonardo

Electronic Almanac Gallery agency.com

Ars

Electronica Sandra

Gering Gallery Time

& Bits: Managing Digital Continuity <nettime> Muntadas, File

Room Komar & Melamid, The

Most Wanted Paintings on the Web Lin

Hsin Hsin Museum PORT:

Navigating Digital Culture Notes Presented at the International Conference, Museums

& the Web, for the panel "Cultural Competition," April 25, 1998.

This version dated 3.25.98. For the most current version, see http://www.yproductions.com/talks/curatingontheweb.html

|