![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Archives & Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

ph: +1 416-691-2516

fx: +1 416-352-6025

info @ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search A&MI |

Join

our Mailing List.

Privacy.

published: March 2004

analytic scripts updated:

October 28, 2010

SHADE Smithsonian-Hunterian Advanced Digital Experiments

Jim Devine, Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, University of Glasgow, Scotland and Carl C. Hansen, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, USA

Abstract

Since first sharing a platform at Museums and The Web in Los Angeles in 1997, The Smithsonian Institution and The Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, on their respective sides of the Atlantic, have worked collaboratively to establish leading edge practices in the field of digital imaging for the scientific and cultural heritage sector. This collaborative project has developed examples of best practice in skills-sharing between the Education and Digital Media Service at the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, University of Glasgow, http://www.hunterian.gla.ac.uk and the Center for Scientific Imaging and Photography at the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian. http://www.nmnh.si.edu

Keywords: QTVR, Virtual Reality, digital, CD-ROM, WWW, Hunterian, Smithsonian

Introduction

SHADE has built on existing informal skills-sharing activities between staff at SI and HMAG to further develop the potential of emergent technologies for the presentation of museum collections through digital media. The primary stages of this project have proved very successful, with SI staff providing expert advice, a stimulating two-way exchange of ideas, and peer review for a number of educational initiatives incorporating interactive technologies such as QuickTime Virtual Reality.

The initial focus for digital experimentation in SHADE has been chosen from a range of our respective collection strengths to provide a digital educational resource for school/college classrooms in the UK and the USA. Topics have been chosen where one partner has significantly more collections material than the other, thus augmenting the digital collections of both and providing an even greater wealth of educational resources to our respective academic end-users. The time is now appropriate to look back:

- to evaluate what we have achieved thus far,

- to assess, with input from our target audiences, how successful we have been in our aims, and

- to map a future course, which may serve as a model for our sector.

Early Days (Digitally Speaking)

How do you facilitate access to a museum's treasured objects and at the same time protect them? That was the question facing many museums in the middle 1990's. The Smithsonian Institution, a complex of 17 museum and research facilities, has untold millions of objects in its varied collections. The scientific collections there are primarily for research purposes, but objects are routinely pulled for inclusion in museum exhibits or for loan to affiliated museums.

Smithsonian curators estimate that 70 percent of the wear and tear on individual objects results from resident and visiting researchers sorting through collections hoping to identify objects for further study. The larger the objects, the more difficult they are to handle, and the more damage incurred. We were looking for a method to allow researchers to search the collections without actually handling objects until they were certain they had found what they needed. Digital images that could be shown on a computer or sent across networks seemed to be the answer, but flat two-dimensional pictures don't always show the details necessary to identify and judge an object.

At that same time the first professional digital cameras were coming on the market, and Apple Computer had introduced some software that allowed us to stitch together numerous digital images of the same object into a virtual 3D representation of the object. Carl Hansen started experimenting with this new technology and found it quite intriguing. The software was free and as a consequence, quite buggy and difficult to use, but eventually he mastered it, at least to the point that he could achieve satisfactory results.

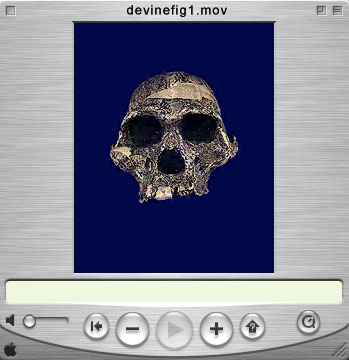

Fig 1. Australopithecine Cast QTVR

This Australopithecine cast http://photo3d.si.edu/COMNET/Anna/Anna2/QTVR/Ausweb.mov (330k file) http://photo3d.si.edu/COMNET/Anna/Anna2/QTVR/Aus.mov (2mb file) was Carl's first attempt at making a QTVR object. It was created using a light stand as a turntable, the first Kodak professional digital camera the DCS-100, and Apple's freeware Object Maker software.

Carl was excited at the potential this new technique offered, and the curators and research scientists loved it. It proved that they could view an object without handling it and in some instances view it better than they ever had before.

The DCS 100 camera is extremely primitive by today's digital camera standards. It weighs in at about 20 pounds, thus requiring the backpack and cables for the hard drive. It cost $25,000, not counting the Nikon F3 camera and lenses required to make it a real camera. Today's consumer grade digital cameras in the $300-$500 range produce better digital pictures and fit into a shirt pocket. But it was the only one available at the time.

A Meeting Of Minds Over Malt!

In 1995, Carl teamed up with Dr. Charles Calvo from Mississippi State University and experimented with the QTVR technology to produce the first Stereo 3D objects. It was an exciting breakthrough, and they took their show on the road.

That year Carl and Charles were presenters at the first ever Museums and the Web Conference in Los Angeles, California. A fellow presenter at the conference was a Scotsman named Jim Devine from the Hunterian Museum at the University of Glasgow. Jim was presenting the potentials of virtual tours on the Web through panoramic QTVR, was intrigued with the Smithsonian's object QTVR presentation, and could foresee where the technology could be used in the area of cultural heritage presentation through distance education, his specialty. Carl and Charles in turn were impressed with what Jim and the Hunterian were doing with the World Wide Web as a medium for reaching a wider audience. Over a bottle of Johnny Walker single malt smuggled into the hotel bar, a plan evolved.

Within a couple of months, Carl and Charles were in Glasgow demonstrating their QTVR techniques and giving a workshop at the University of Glasgow's Department of Computing Science. In exchange, Jim arranged access to a life-sized hominid skull cast and a modeled recreation of its facial features.

Not satisfied with the usual QTVR object movies, the three of them brainstormed and came up with a new technique for using the QTVR software to produce controllable morphs.

Fig. 2 Image extracted from Homo habilis morphing sequence

At that point SHADE was in its embryonic state. The following year, Jim Devine went to the Smithsonian to tour their digital labs, and that is when the decision was made to formalize the project. The plan was to meld the digital expertise of Carl's center at the Smithsonian with the Hunterian's educational outreach expertise. It was felt that interactive digital technologies would provide cultural heritage organizations with opportunities to utilize emergent computer technologies to present their cultural resources for educational users in new and increasingly innovative ways. This ability to present information electronically can be used to bring the user together with museum artefacts and the sites and monuments from which they originally came, thus digitally placing the objects in their archaeological contexts.

The first attempts at what Jim Devine, with tongue firmly in cheek, called "virtual repatriation" involved the Smithsonian digitally taking Henry the elephant in the Natural History Museum's rotunda out of his museum context and placing him back on the African savannah. http://www.mnh.si.edu/museum/VirtualTour/Tour/First/Elephant/index.html

Jim and his computing science students upped the ante by morphing the Egyptian mummy at the Hunterian back to the tomb and allowing users to "open" the sarcophagus and then "remove" the mummy's bandages to reveal x-rays of its skeleton. http://www.hunterian.gla.ac.uk/museum/egypt/qtvr.html

With the increasingly sophisticated software applications being developed, the opportunity now exists to allow a gallery visitor, whether "virtual" or physical, to "peel back" the layers of an object to examine the internal structure.

The first stage of SHADE has been to establish common digital image capture standards based upon the tried and proven high-quality PhaseOne Hasselblad solution.

This system allows automation of the QTVR object capture process. It can simultaneously produce two QTVR object movies at different resolutions. The larger would be for research or CD-ROM purposes, the smaller for use on the WWW. For research purposes we would make the largest object movie full resolution (18 mb per image) and one image every 10 degrees or 36 frames per movie. This produces a very large file. The Web version would usually be reduced to 18 frames at a much lower resolution usually a maximum of 320 pixels on the longest side.

SHADE has grown out of existing informal skills-sharing activities between staff at the Smithsonian and the Hunterian, and the goal is to further develop the potential of emergent technologies for presentation of museum collections through digital media. The first stages of this project have proved very successful, with Smithsonian staff providing expert advice and peer review for the Hunterian's Hominid Evolution CD-ROM project, incorporating digitally captured skull specimens in QTVR of all known hominids. This collaboration continues to produce a stimulating two-way exchange of ideas.

As a recognized "international" project with the combined cache of the Hunterian and Smithsonian names, the partners have been able to negotiate substantial savings on very expensive equipment and at times donations of equipment they couldn't afford to purchase. They can frequently arrange trial loans of new equipment to test before purchasing. Commonality of equipment helps ensure that these high standards of image quality are maintained and that digital experiments being conducted at each partner location can be replicated accurately at remote locations. This also provides opportunities to test the reliability of the partner's broadband networks when transferring large image files across the Atlantic. The Hunterian's close collaboration with the Computing Science Department of the University of Glasgow gives the project access to another necessary commodity, highly skilled and motivated student interns.

From The Lab To The Field

Much of the work at the Hunterian has involved teams of students from the Department of Computing Science who have experimented with a wide range of multi-media presentation techniques. The students have benefited greatly from dealing with real clients seeking solutions to real challenges. In each project set for academic assessment, there have been interesting technical challenges in using existing software and also major design issues, but these have to be balanced against the Museum's desire to capture large quantities of data. The compromise often reached is to regard the student projects as providing a framework for the final product which can then be expanded by Museum staff as time permits, or by paying somebody to carry out the data capture required to fill in all the details. This has led to the creation of Hunterian Scholarships whereby the best students can apply for funded internships over the vacation periods to take projects to completion.

The majority of projects involving student participation have been conducted locally at the Hunterian, with remote input and peer review from the Smithsonian. However, as part of their SHADE input, the Hunterian had been keen for some time to undertake a major QTVR fieldwork project at a distant location from their lab facilities. The virtual tour projects in QTVR which had been undertaken by the Hunterian up to that point had been fairly small-scale indoor tours of Hunterian galleries http://www.hunterian.gla.ac.uk/mackintosh/mackintosh_index.html and limited outdoor tours of small sections of archaeological sites such as the Antonine Wall http://www.hunterian.gla.ac.uk/museum/romans/ANTONINE.HTM constructed by the Romans in Scotland.

These were easily reached from the Hunterian, and were in relatively close proximity to the development facilities in the Museum and the Computing Science labs at the University of Glasgow. The challenge of an archaeological expedition would test their capacity to put a team into the field to create a virtual tour of a large scale archaeological site, and be able to test all the digital imagery for QTVR operability whilst still on-site, without recourse to the home lab facilities. This would allow them to determine the logistics involved in providing all the mobile technical equipment and back-up necessary to support such a team in the field. After some discussion and negotiation with the British School of Archaeology at Athens and the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, it was agreed that an ideal site for this type of virtual tour treatment was the palace complex of the legendary King Minos, at Knossos in Crete. http://www.bsa.gla.ac.uk/knossos/vrtour/index.html

The great volume of visitors to Knossos presents critical conservation issues for the Greek Archaeological Service. In many cases the pressure placed on the structural remains has led to large areas of the archaeological site being closed to the public. The creation of a virtual tour of the site including these closed areas was aimed at providing the on-line as well as the on-site visitor with an interactive multi-node tour of this world heritage site, incorporating those areas that they would otherwise be unable to see.

The resulting digital imagery can also serve as a conservation tool for the Greek Archaeological Service. The material has been made available on-line to form a valuable educational resource for scholars at all levels, from school pupils and their teachers to academic researchers in the fields of archaeology, art history, and cultural heritage management.

Important lessons were learned by the expedition team in coping with the vagaries of climate, dust, absence of electricity, and over-abundance of tourists and raki (the local aperitif): all of this whilst trying to coax the maximum output from somewhat delicate photographic and computer equipment. That the entire Minoan Palace plus some nearby associated sites were digitally captured, and around one hundred panoramic nodes processed, including many retakes, on-site, and within the agreed timescale of six days, was a major achievement.

User Evaluation

Throughout all of SHADE s activities, the partners have sought the input of a broad range of end-users of their digital resources. Museums have a responsibility to provide educational resources to all levels of scholars, from elementary school students to post-doctoral researchers. The Smithsonian and the Hunterian partners have sought to engage the widest possible audiences in developing their digital educational resources.

The Smithsonian's Natural History Museum has the largest single collection of academic researchers in any one building in the world. They have constantly provided excellent feedback and encouragement. Scholars have frequently commented on how the provision of a high-resolution digital image of an artefact, captured under expertly lit conditions, has allowed them to identify artefact features which are not obvious even when the actual artefact is examined by hand. Carl and his team are in heavy demand, supporting Smithsonian staff engaged in leading-edge research around the world. He is currently engaged in the highly controversial "Kennewick Man" study. http://www.mnh.si.edu/arctic/html/kennewick_man.html

From the outset of its pioneering work in the provision of distance learning resources via the Web, the Hunterian has developedits materials in consultation with a wide range of user groups. In addition to the university academic community, the institution has taken on board teachers and students from junior and senior schools in Scotland and the US. These include schools in remote areas like the Outer Hebridean island of Barra, in the Western Isles of Scotland, and those in major urban conurbations such as Glasgow, and Alexandria, Virginia, on the outskirts of Washington DC. All of the participating schools have provided excellent feedback on the various projects undertaken by the SHADE partners. The Hunterian has been successful in securing grant support from national agencies such as SCRAN (Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network) to develop online and CD ROM based educational resources targeted specifically at school curriculum support. The Hunterian is currently in discussion with the Scottish Museums Council to develop a major research project in Scotland to assess museum Web resource provision and evaluate audience take-up.

Fig. 3. Students in Minnie Howard 9th Grade School in Alexandria Va. evaluating the Hunterian"s "Romans in Scotland" online educational resource.)

As stated in the introduction, this is a timely opportunity for the SHADE partners to look back over the past six years since that very first contact at Museums and The Web in Los Angeles. It has been useful to reflect on and evaluate what has been achieved thus far, and to assess, with input from the target audiences, how successful the partners have been in their aims, and where, in the language of their school users' report cards, they "could do better"! The next stage will be to gather wider input to the evaluation process, collate that feedback, and disseminate the results to the museum community. SHADE does not have, and probably never will have, all the answers to developing digital resources that meet the aspirations of the varied museum audiences. But the partnership has made some very useful steps in the right direction. This hopefully can help map a course ahead that may serve as a model for our sector.