![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Archives & Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

ph: +1 416-691-2516

fx: +1 416-352-6025

info @ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search A&MI |

Join

our Mailing List.

Privacy.

published: March 2004

analytic scripts updated:

October 28, 2010

Building a Festival Web Site: An Uncommon Collaboration

Kimberly Freeman, The Silk Road Project, Inc and John Gordy, Freer Gallery of Art/Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, USA

www.silkroadproject.org/smithsonian

Abstract

The Smithsonian Institution's Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage (www.folklife.si.edu), the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (www.asia.si.edu), and the Silk Road Project (www.silkroadproject.org) collaborated to produce a Web site documenting the 2002 Folklife Festival which brought together the arts, music, and traditions of the Silk Road for over 1.3 million visitors on the National Mall in D.C. Although a foundation was laid ahead of time, the Web site was constructed on-site in a trailer as the Festival unfolded, taking in and responding to the textures, sounds, events, energy, and people that comprised the event.

Building a festival site while the Festival unfolded left little room for error. But producing the site during and within the Festival brought vibrancy and immediacy that would not have been possible had the site been fully designed before the event began. The Web site was thus part of the live event, influenced and inspired by the colors of silk, sounds of music, smells of foods. As videographers and photographers documented events, pages were designed, coded, and launched.

The festival brought people together from around the world. We freely and openly shared knowledge, ideas, and resources becoming an example of collaborative exchange that the Silk Road symbolizes.

Keywords: Collaboration, Cultural Event, Festival, Documentation and Archive of Live Event, Silk Road, Smithsonian Folklife Festival, Documentation

Background

The Silk Road Project is a not-for-profit music and cultural organization founded by cellist Yo-Yo Ma in 1998. Through its programs — a two-year worldwide concert tour performed by an international group of musicians, music commissions awarded to Silk Road composers, and educational materials disseminated to schools — the Project furthers its mission of building connections and creating trust across cultures. Phase one of the Project's activities culminated in the two-week 2002 Smithsonian Folklife Festival on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. The Festival brought together 400 musicians, artisans, and craftspeople from 25 countries along the Silk Road. 1.3 million people came to the Mall to hear music, taste food, and watch and talk to artisans.

Part of the Silk Road Project's mission is to act as a catalyst for refining and defining collaborative work, often bringing disparate groups together to work with one another in imaginative ways. In planning for this event, the Project worked with not only the Smithsonian Institution's Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage which runs the annual Festival, but also the Freer/Sackler galleries, which organized a Silk Road exhibit to tie in with the 2002 Festival. The Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Freer Gallery of Art together form the national museum of Asian art as part of the Smithsonian Institution. Each of these organizations shares a mission of encouraging an understanding of Asian art and culture to a wide audience — clearly a match with the Festival's theme of the Silk Road.

The historical Silk Road, an exchange network of trade routes that crisscrossed Eurasia long before today's global economy (from about the 2nd century B.C.E. through the 14th Century C.E.), served as a major conduit for the transport of knowledge, information, and material goods between East and West resulting in the first global exchange of scientific and cultural traditions. Merchants, ambassadors, and pilgrims transported crafted goods and raw materials across political and cultural boundaries: spices, precious metals, musical instruments, rare medicinal herbs, objects used in worship and ritual. Silk, the most famous of these commodities, reached the Mediterranean by the first century B.C.E. from production centers in China (www.silkroadproject.org/silkroad/overview.html and www.asia.si.edu/exhibitions/online/luxuryarts/default.htm).

Web Site Preparation

Prior to the event, the organizations independently prepared Silk Road materials for the Internet: the Silk Road Project added information on instruments, musicians and composers of the Silk Road, as well as an historical overview and a detailed map of the Silk Road; the Freer/Sackler created a site compiling all of the Silk Road-related activities of the galleries.

Fig. 1 The Silk Road Project Web site focuses on the music of the Silk Road. (http://www.silkroadproject.org)

Fig. 2 The Freer/Sackler special Silk Road exhibition site showcases artifacts from across Asia. (http://www.asia.si.edu/exhibitions/online/silkroad)

The Project had an established identity of bright warm colors and horizontal lines. Long before the Festival materials were developed, the Project sent preliminary layouts to the Freer/Sackler so that their stripes and colors could be integrated into the galleries' marketing materials. As a result, the two organizations had independent identities that played off one another. By sharing color palettes and general art direction, the resulting color schemes and visual themes brought unity to these separate projects.

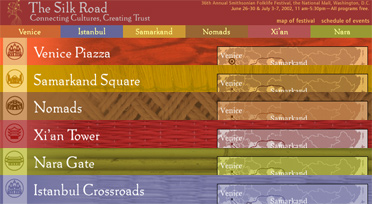

Fig. 3 The Silk Road Project homepage navigation uses horizontal lines in six colors. The logo rests on a mountain texture taken from a topographical map of the Silk Road.

Fig. 4 The Freer/Sackler uses stripes in the same colors as the Silk Road Project on top of a black and white photo of mountains.

It's easy to believe that just providing links to one another means collaboration. At this point, our work together was similar to other collaborations, not extending much beyond reciprocal links. But, a true collaboration is an exchange that changes the outcome of both people's efforts and entails a deeper level of involvement. In the next stage of work, the collaboration became an exchange of ideas, ways of working, labor, and talent. The efforts were no longer independent; we were working towards one goal.

The Festival Web Site: Structure & Goals

The Festival site became a collaboration out of necessity. Not one of the organizations had the resources required to launch a site on its own, but by pooling our resources we were able to put together the equipment and team to produce a site. Much of the content that was being developed for the Festival (information signs, a passport for children to use on their day's long journey through the Festival, etc.) provided the bulk of written material for the site. A trailer on the Mall was set up with high-speed Internet connections, and outfitted with computers, digital cameras, video cameras, scanner, and a 360-degree photo lens. A staff of Folklife photographers provided event photography. The trailer team consisted of a producer, programmer and editor who came to Washington a week prior to the event. The Freer/Sackler Gallery loaned a producer to help the team, who provided skills as a digital photographer, programmer, coder and designer.

The respective Silk Road online presences that launched prior to the event provided only historical background and general information about the Festival and the Silk Road (visitor information, historical overviews, etc.). However, the mission of a dedicated 2002 Folklife Festival site was not only to provide information, but also to convey the spirit and flavor of the event itself. The challenge in translating that spirit online was that the event had yet to begin; there were diagrams and text and lists and outlines and a huge setting of tents and stages, pavilions, kanats (handmade fabric walls dividing sections of the site), yurts (small portable tents for living), even camels. Only on opening day when performers danced, sung and played on those stages would we get an idea of the kind of chemistry that might be born out of the Festival.

The goals of the Festival site were:

-

To impart the experience of the Festival to those who might not be able to attend. (Photos of the live Festival, for example, as well as video clips of performances.)

-

To archive information and images. (Since the volume of information was more than anyone could absorb on a day's visit, the site would serve as an archive of the many signs with information on the history, geography, traditions, arts, religions of the Silk Road.)

-

To enhance and extend the experience of those who did attend the event. (Before coming to the Mall visitors could download detailed schedules (updated every evening) of performances for the following day, and after leaving they could explore areas of interest, or see a video clip of their favorite performance. Children could download a passport to guide their journey through the Festival. They could print it out, bring it to the Festival, and get stamps at designated stations. When they filled their passports, they would receive a prize of a special commemorative Silk Road coin.)

Planning the Site's Architecture

Five days prior to the opening, as the Festival unfolded in front of us, we met on the front steps of the Freer Gallery. Inspired by what we saw, we came up with the basic architecture of the site, which would follow the organization of the physical site itself. Five sentinels of arrival (Venice, Istanbul, Samarkand, Xi'an, Nara) which each had their own distinct design influenced by the regions they represented, would become five main sections of the Festival site along with a sixth area (Nomads).

The Festival designers struggled with what to include, how to achieve geographic and cultural diversity, how to strike a balance between comprehensiveness and still benefit from the clarity of fewer clear representations, above all, how to layout the information in a way that would make sense to a public that might enter the Festival from any direction on the Mall. Much of the work of the Festival planners, benefited us. The problems and needs of the physical site were paralleled in the Web site. Visitors to both the Festival and Web site were presented clear paths to follow, but were in command of their own experiences and could be drawn by their interests to different areas.

Designing the Site: Opening Day Launch

The site architecture came from the layout of the physical space. The character of the Web site came from hand-crafted materials: the bamboo gates became a textured background for Nara, Ventian paintings became a texture for that section of the site. The positive side of our predicament (creating the site on the fly) meant that we were opening ourselves to react to the moment letting the inspiration come from the Festival itself.

We took hundreds of photos and created a quick intranet site to reference them. We were particularly interested in the textures of the various materials brought to the Festival — these hand-crafted materials represented, to us, the essence of the Festival.

Figure 5. Textures of the 2002 Smithsonian Folklife Festival (clockwise: Chinese hand-painted porcelin, bamboo gate, wooden blinds, silk worm cocoon spiral). Photos taken on-site. (http://www.asia.si.edu/beta/textures/)

Once we saw and captured this incredible material, we wanted to not only feature the crafts themselves, but to make them an intrinsic part of the site itself. We integrated our favorite textures into the navigation for each main section of the site. So, each artifact underwent a long journey: from the artisan's home country in Central Asia where it was brought to life at the artisans hands, it was brought to the National Mall in D.C. where its creation was demonstrated for crowds of visitors, and then captured digitally on our cameras and incorporated into the Festival Web site where it would be seen by a worldwide audience of millions.

Figure 6. The site's navigation incorporated texture photos taken at the 2002 Smithsonian Folklife Festival, a different texture for each of the six main sections. The navigation, thus, was of the Festival itself.

The Spirit of the Festival

The Festival was inspiring. Huge crowds braved the heat, and we saw fabulous music and dazzling performances. We began to understand the Festival; it was no longer abstract. Footage and pictures began flooding in. We had a tremendous amount of visually-stunning material. The challenge, with limited resources and staff, was to pick and choose the right ones to use.

Figure 7. A video clip featuring a Tuvan throat singer. Being able to post footage of the opening ceremonies on opening day was thrilling.

The idea of the Silk Road — individual exchanges between traders who could each gain from the interaction — inspired our own methods of working together. Participants from around the world gathered for two weeks to make art and music together. Many performers and artisans had never left their own countries, but at the Festival they united to share their cultures and arts freely with each other and the world. In similar fashion, we were learning and sharing from one another — experiencing our own Silk Road story of exchange.

The record-breaking heat of that two weeks meant that our office, the air-conditioned trailer, was a popular rest-stop for the over-heated Festival participants and performers. It was a haven from the road, the sun, the heat, the electrical storms and the crowds. It was inspiring to have Yo-Yo Ma and the members of the Silk Road Ensemble practice in the trailer, and look over our shoulders as we coded the site. Imagine producing a site with a live soundtrack of music from the region we were trying to represent playing in the background in our workplace! We felt as much a part of the Festival as those on stage. There was never a doubt of what we were doing or why we were doing it.

Reaching our Audience

As Web-workers, usually removed from our audience, it was exciting designing a site for a Festival that drew 1.3 million people over the course of two weeks. We could just peek outside our trailer door and see the crowds, which was so different from our usually invisible online audience. We would post something in the evening and see people reading print-outs of it on the train the next morning. The site was more popular during the Festival itself than we had anticipated — we needed to upgrade for additional server space three times in the first two days to keep up with the rate of traffic of 8,000 visitors in a day. And, that was just the beginning. The site continues to receive a steady stream of visitors long after July's trampled grass on the Mall grew back, browned and was snowed over.

The site remains an important source of information for visitors from the actual Silk Road, some of whom have reported back to us that they check-in regularly. During the Festival one of the Mongolian translators bowed as he said, You cannot know how grateful we are, in the Gobi desert, for your Web site. He continued on to say that the site provided those in his country connection to the outside world that they craved, and the site gave family members of Festival participants a way to see and understand the event. We were touched and motivated by what he shared with us.

Lessons Learned: Tips for Those Preparing a Site for a Massive Live Event

One of the peculiarities of doing this site was that there is no next time. We would joke, next time we invite a million people to the Mall we should . . . . However, we would like to pass along our two-weeks-worth of wisdom, hoping this might be helpful for even smaller scale live event sites:

-

Build flexibility into your designs before the event, so that you can respond to the inevitable changes that will happen to the design and text. (examples: Strip out approved text before the event and use stylesheets.)

-

Have one shared drive on site, with plenty of space. Triple what you think you need

-

Network your computers so that you can easily share files.

-

Automate calendar updates. The schedule of events will change during the course of the event.

-

Buy twice the estimated needed number of media cards (or other storage) for digital cameras and video cameras.

-

Update everyone's software and fonts before the event. Use the same versions.

-

Devote one workstation to video/audio crunching.

-

Provide solid examples for art direction for photographers and videographers before the event. Give them examples.

-

Develop a system ahead of time for cataloging images with standard naming conventions. Share these conventions with your photographers so they can name their files according to your system.

-

Provide ample post-production time. When the event is over and everyone's going home and getting some rest, plan on still being in high production mode, processing the volumes of material that surely weren't able to launch during the event.

While working so closely together, we learned new ways of working. We each had enough experience in building Web sites that we had settled into our own methods of creating. Working on a common project forced us to see and understand each other's process. Keeping flexible, we each forged new methods, from the influence of having someone there with an outside perspective to challenge assumptions.

Conclusion

Collaboration means working together by sharing people and ideas, not just resources. Often when two organizations meet to collaborate online, the result is simply exchanged links. Loaning a staff member to another organization, a sort of cultural exchange student program for professionals, results in a more profound collaboration. Just as the members of the Silk Road Ensemble learned from each other, listening to each other's styles, we improvised a new way of working, creating a unified whole from different talents and styles.