![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Archives & Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

ph: +1 416-691-2516

fx: +1 416-352-6025

info @ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search A&MI |

Join

our Mailing List.

Privacy.

published: March 2004

analytic scripts updated:

October 28, 2010

Designing a bilingual virtual archival experience: the Museum of Russian Culture collections at the Hoover Institution Archives

Polina E. Ilieva, Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University, USA

Abstract

The Hoover Institution Archives recently concluded a joint project with the Museum of Russian Culture in San Francisco, funded by an NEH grant to process and microfilm the Museum's most significant archival holdings. This project was concluded with the launch of a bilingual English/Russian web site that has created a unique virtual archival space.

Founded more than 50 years ago, the Museum of Russian Culture is one of the major repositories of Russian émigré documents, and also contains materials related to the history and culture of Russia.

I will demonstrate how the major task of creating an authentic Russian language web experience Ů more than just a simple translation of the English site - was accomplished. This paper will analyze and show-case some of the challenges and solutions in designing a bilingual web experience, including, but not limited to technical, cultural, quality assurance and usability testing, copyright issues, use of a bilingual search engine, site promotion in the USA, Russia and other countries, management of reference questions and user feedback issues.

I will show how an elaborated virtual archival experience was created that included in some way all the components of a "brick and mortar" archives: finding aids, some documents (photographs), reference materials (biographical notes), search, and reference questions options. The site serves both serious researchers and the general public, including the families and descendants of Russian émigrés. Historians can use the online register to easily locate the exact box and folder they need for a specific topic. The site presents numerous vintage photos and background information to hold the interest of those simply curious about the culture of "Russia Abroad."

Keywords: archives, virtual, bilingual, Russian, English, finding aids, cultural heritage

Introduction

The first conflict that generated an enormous number of refugees in the last century was the Russian Revolution of 1917. When the ideological confrontation in Russia evolved into a civil war, the people were forced to subdivide into those on "our side" and those on the "other side": or Red and White. As a result, according to rough estimates, more than 1.5 million people left Russia between 1917-1922. They elected to leave the country, hoping to return home someday and destroy the Communist regime.

Major destinations for these refugees, who were later referred to as "Nansen refugees," were Europe and the Far East (in particular China). [Nansen refugees were "any person of Russian origin who does not enjoy or who no longer enjoys the protection of the Government of the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics and who has not acquired another nationality" - Arrangements of 12 May 1926, as quoted in Vernant, 1953:54]. The territory surrounding the Chinese Eastern Railway (KVzhd), with its center in Harbin, attracted thousands of Russians escaping the Bolshevik regime. There, they found a place to live and to work. Japanese occupation of Manchuria forced many of these immigrants to move to Shanghai. Later, fear of a forced repatriation to the Soviet Union after the establishment of the Communist regime in China made thousands of White Russians seek resettlement in United States and Australia.

World War II also brought a big wave of displaced persons (DP), former citizens of the Soviet Union and migrés from Eastern/Central European countries that had become part of the Socialist camp, to the United States. These newly arriving refugees joined an existing Russian émigré community with a long history. Surviving the turmoil of the Revolution, the Civil War and the Second World War they managed to preserve and carry with them to new places their culture and memory: many brought with them family albums with photographs, memoirs, official documents issued by Czar Nicholas II or the Provisional Government, correspondence with members of the czar's family and with famous writers and artists, as well as letters from ordinary citizens of the Soviet Union. In addition, Russian communities abroad also amassed a wealth of materials illustrating their life and activity in different countries: speeches, writings, and correspondence by well-known émigré figures, such as Vladimir Nabokov, Vasilii Maklakov, Zinaida Hippius, Maria Vrangel, Alexandra Tolstoy, to name a few. There were also photographs and programs of performances by amateur theatre companies and choruses, archives of Russian-language newspapers and magazines, schools and clubs, documents of non-profit, charitable, veterans, historical, boy scouts organizations and other societies that played an important role in the social and political life of the Russian community.

The Museum of Russian Culture in San Francisco and the cultural heritage of Russian emigration

Founded more than 50 years ago in San Francisco, the Museum of Russian Culture became one of the few repositories in the world specializing in Russian émigré documents and other materials on the history and culture of Russia. Since then, generations of enthusiasts have been collecting and displaying these treasures. However, being a non-profit organization staffed by volunteers and open only for a short period of time each week, the Museum didn't have the opportunity to provide easy and wide access to its holdings.

In 1999, the Hoover Institution Archives received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities for a two-year project to process and microfilm the Museum's most significant archival holdings. The primary goal of the project was to preserve these collections and make them available to scholars in the reading room of the Hoover Institution Archives in microfilm form. As a result of the project, 85 collections, consisting of 475 manuscript boxes of materials, were organized, described, and microfilmed.

This project coincided with a new interest in the study of the history of emigration and its fate that has arisen in Russia in recent years. According to Andrei Popov, director of the Research Center for Russian Emigration in Moscow (Popov, 2001, p. 5):

›"The cultural heritage of emigration influences the development of social processes in Russia, philosophic, historic, economic, religious ideas.... Russian emigrants were able to preserve the best traditions and culture of Old Russia.... Now, when the Russian state painfully searches for its violently interrupted historical path, the message that was carried on by Russian emigration becomes extremely valuable."

During the long years of the Communist regime, the topic of emigration could not be freely discussed, and Russian historians, unable to travel and communicate with their colleagues from the West, were unaware of the scale of archival Rossica abroad. (including all types of archival materials of Russian origin outside of Russia). In the last decade, Russian scholars and their colleagues in other countries have published numerous monographs and articles describing collections of repositories with materials related to Russia. Patricia Grimsted (Grimsted, 1993, pp. 469-470), a respected scholar of Russian archives, emphasized ten years ago the importance of the creation of a database for archival Rossica throughout the world after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the reestablishment of relations with Russian émigrés:

›"Much may be gained for a true cultural renaissance by a concerted effort on cultural, and specifically archival, preservation, and by the professional description of those materials that have been preserved wherever they may be, including known details about their migration and losses en route. In this manner, they may be studied, correlated with related materials in Russia itself or in other parts of the former USSR, and duly appreciated by present and future generations."

The emerging importance of archival Rossica for present day Russia prompted the Hoover Institution to reconsider its original online offering of a general description with a few photographs. Three main points contributed to the decision to use the Internet to make the results of the project accessible to the general public and researchers around the world: first was the wealth of materials and their historical and cultural importance, second was the renewed interest within Russia in the history and fate of the White Russian emigrants who during the Communist regime were considered by the Soviets to be "enemies of the state," and third was the availability of the web-design expertise of the project's assistant archivist.

Project goals

The primary goal of the project was identified during the Research stage: to facilitate public access to, and disseminate information about the above-mentioned 85 archival collections. The primary audience was identified as researchers of Russian history worldwide, including Russia; the secondary was students working on the history of migration, and the general public doing genealogical research or just browsing the Internet. For this reason, it was decided to make the site bilingual in Russian and English. Only HTML and some JavaScript were used in the site design, for the following reasons: first, users outside the United States may not have access to the latest web technologies, second, their Internet connection may be slower and more expensive (in Russia, connections are mostly dial-up access where users have to pay by the minute).› A benchmark survey of library and archival sites was conducted in the United States as well as in Russia. The experience of the Library of Congress in its› "Meeting of Frontiers" web site was examined. On its "About the Project" page (http://international.loc.gov/intldl/mtfhtml/mfhome.html) it describes itself as:

"A bilingual, multimedia English-Russian digital library that tells the story of the American exploration and settlement of the West, the parallel exploration and settlement of Siberia and the Russian Far East, and the meeting of the Russian-American frontier in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest."›

The site provides access to digitized archival materials from the collections of the Library of Congress, the Rasmuson Library at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the Russian State Library in Moscow, and the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg. This web site displays text in both languages on the same page and users click on the word Русский to be linked to the Russian text that is displayed on the same page after the English. But it was concluded that for the Museum of Russian Culture project such an arrangement could lead to confusion; first time users who don't know English might assume that there is no Russian translation and may be discouraged from using the site.

Also analyzed were: the web site of the Russian State Library (www.rsl.ru), that has two versions: Russian and English (http://www.rsl.ru/eng/defengl.asp), with slightly different information and layouts geared to the particular audience; the web site "Arkhivy Rossii" (Archives of Russia, http://www.rusarchives.ru), that is an official site of the Federal Archival Service of the Russian Federation; and the Russian-language web site of the project "Russkoe Zarubezh'e" (Russia Abroad, http://www.zarub.db.irex.ru) that includes three databases (an encyclopedic dictionary of Russian emigration, a guide to information on Russian emigration in the Moscow archives, and a bibliography of Russian emigration), and seeks to provide the most complete information about Russian emigration.

In analyzing these web sites, special importance was paid to the naming conventions and ru.net lingo, so the Russian labels and navigation bars would reflect the ru.net concepts and create an authentic Russian language web experience, and not a simple direct translation from English. For example, Russian sites use the word Главная "Major," meaning "Major page" instead of "Home page". Based on the above research, and within the broader goal of offering easy access to unique archival materials, the top three priorities for this site were identified as follows: to be easy to use, quick to search, and with the necessity of designing two identical sites in Russian and English.

Project structure and design process

Digitization of the microfilms wasn't included in the project (the copyright to the documents belongs to the Museum of Russian Culture). It was decided that the virtual archival experience should include all components of a "brick and mortar" archives, except the holdings themselves: finding aids, photographs, reference materials, search, and reference questions options. This design gives a diverse audience the opportunity to locate materials: researchers can prepare for their visit to the archives by studying the registers, and request the necessary microfilm rolls in advance; students researching the topic of migration can read the overview of the materials on Russian emigration in the Museum of Russian culture in San Francisco, as well as short biographical notes on particular personalities; occasional visitors will enjoy leisurely browsing through the part of the site that displays rare photographs. The overall method of information organization for this site is by category: home, projects, collections, help, search. On each page users have the option to choose between Russian or English language links and be redirected to the corresponding language site.

Figure 1: The Splash page of the Hoover Institution Archives Russian Collections http://www.hoover.org/hila/ruscollection

The home page gives an overview of the site and its sections.› The official title of the site is the Hoover Institution Archives Russian Collections, because eventually it is planned to add other collections following the same format. However, even now the Museum of Russian Culture collections are specifically identified and have the subtitle "Museum of Russian Culture Microfilming Project" on their pages. The home page also includes the following sentence stating the nature of the site: "All information on this web site is provided solely for noncommercial educational or scholarly purposes."

The "Projects" page in the future will provide information on special projects related to the Russian collections of the Hoover Institution Archives. Presently it contains only one project Ů the Hoover Institution - Museum of Russian Culture microfilming project funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities (1999-2001). It describes in detail the history of the Museum and its mission, and gives an overview of selected collections in its possession that have been microfilmed. This page also contains a list of contributors, as well as contact, access and copyright information.›

The "Collections" page provides a list of 85 collections with links to their registers, as well as biographical sketches and photographs for 51 collections. The method of organization is alphabetical.› Finding aids for 13 collections were encoded in the EAD (Encoded Archival Description) format, and posted on the Online Archives of California (OAC) in accordance with an agreement between the OAC and the Hoover Institution. Presently, the Hoover Institution Archives has more than 850 electronic finding aids available for viewing by remote visitors, and eventually registers for all indexed collections will be placed there (http://sunsite2.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/oac/hoover). As of February 2000 only 8 percent, or 160 out of the 2,000, archival and manuscript repositories in North America that had web pages were providing online access to at least four full finding aids (Tibbo and Meho, 2001).

The importance of preserving the exact structure of the registers was taken into consideration when deciding how best to display the remaining 72 registers. It was decided to convert them into PDFs. The registers were compiled in English, and even the Russian part of the site refers users to these English versions. It was assumed that Russian users could read proper nouns written using transliteration, or if they found a useful reference in a biographical sketch written in Russian, they would write to ask about it. Using these online finding aids historians can easily locate the exact box and folder they need for a specific topic, and later can either visit the archives and work with the documents or request photocopies.

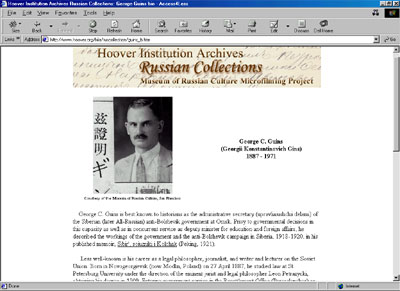

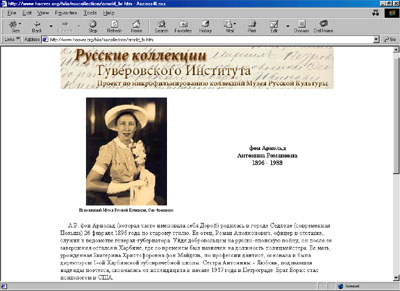

Fifty-one (51) collections for which short bios were written were selected for their historical importance and the availability of background information.› Each bio with two exceptions, has a photograph of the profiled person. In cases where the collection had a significant number of additional photographs, some were included on a separate page linked to the bio.› Other resources besides processed collections, were consulted in order to get accurate details on birth and death years (it was indicated in parentheses if the date was according the Old (O.S) or New (N.S.) style), and on places people lived, taking into account that proper names for some geographical locations in Russia changed several times during the past century, or that cities that previously belonged to the Russian Empire are now part of the independent states (for example George C. Guins was born in Novogeorgievsk, Russia (now Modlin, Poland)). All Russian, Polish and other foreign names were spelled according to the rules of transliteration of the Library of Congress, with English translation given in parentheses.

Figure 2. Page with the biographical sketch of George C. Guins

Figure 3. Page with the biographical sketch of Antonina Romanovna Von Arnold (In Russian)

All text for the site was first written in English and then translated into Russian by the archivist (bilingual English/Russian speaker) and the assistant archivist (native Russian speaker), and proofread by another archivist (also a native Russian speaker). All proper nouns in the final Russian text had to be checked as they were sometimes distorted through the dual translation (several documents in the collections had been translated by emigrants without proper knowledge of English) and official names of organizations or committees had to be found.

In selecting the search engine there were two major issues: the ability to search PDF files and Russian-language pages. Presently MondoSearch is being used with good results.

Visual design

A sepia tone was used to convey the old and rare look of the archival collections for pictures, titles, and for a background for the splash page. Brown and orange colors were chosen for the font. All graphical elements of the site are quickly downloadable. In selecting the images for the site, the most interesting and relevant pictures from the archival collections were identified, then scanned and adjusted in Photoshop (size, defects, color, etc.).

Web site production

During the next stage, the site prototype was created and tested by potential users for ease of navigation, information, layout, internal/external links, labeling, content, content management, copyright, and so on. After the analysis of their feedback, necessary adjustments to the final version of the site were made.

The final version of the site was produced in Dreamweaver using Fireworks, Photoshop, HTML and JavaScript. A market research of the Russian Internet environment (.ru) was conducted and, as a result, the following character encoding for the Russian language pages to be used in the <meta> tag was selected: Windows 1251 (<meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=windows-1251">). The site can be successfully viewed on a Windows platform using Microsoft Internet Explorer and Netscape Navigator, which both support this character set.› The newest Macintosh operating system "Jaguar" (Mac OS X v10.2, http://www.apple.com/macosx/) has a built-in internationalization (it has full Unicode support and supports non-Roman alphabets), and correctly displays Cyrillic characters. Users of earlier Macintosh operating systems needed to install specific fonts to view these pages.

A beta version of the site was tested by potential users on different platforms and browsers, in the US, UK, France and Russia. Various bugs were identified by the beta testers, and, based on these valuable responses, corrections and enhancements were made to address misspellings, missing labels, malfunctioning internal and external links, the search feature, and so on. The overall response on usability testing was very positive.

Launch and post-production maintenance

The site was launched in November 2001 (presently it can be found at the following url: http://www.hoover.org/hila/ruscollection) and was officially inaugurated at a meeting of the staff of the Hoover Institution Archives and volunteers of the Museum of Russian Culture and members of the Russian émigré community. Several weeks before the launch, a list of potential users in different countries was created. It included representatives of the Russian émigré communities, Russian scholars, libraries and archives with extensive Russian holdings, and university centers for the study of Russia. A press-release announcing site's launch ("Hoover Institution launches web site to conclude NEH grant to process and microfilm archival collections of the Museum of Russian Culture") was sent to individuals and organizations interested in its content. The database on the history of Russian emigration, "Russkoe Zarubezh'e" (Russia Abroad) (http://www.zarub.db.irex.ru) was asked to include a link to the site, so it would be visible to the community of users interested in this topic.

In order to make the site accessible for indexing for Russian search engines Russian-language content for description and keywords <meta> tags were carefully prepared. A search for the "Museum of Russian Culture collections" on Google and Yahoo! retrieved the site's url ranking in the top two, a search for particular persons whose collections were part of the project, with the use of only a family name generally retrieved the site's url ranking in the top six; a search in the Russian-language Google generally retrieved the site's url within the first five items. Two major Russian search engines Yandex (http://www.yandex.ru/info/webmaster.html) and Rambler (http://www.rambler.ru/doc/recommendations.shtml) do not send their robots to index web sites outside of the "Russian net" that include the following domains: ru, su, am, az, by, ge, kg, kz, ua, uz (these belong to servers in the Russian Federation and some other countries of the former Soviet Union). Both search engines suggested that sites from other domains with significant information in Russian that may be of interest to the Russian audience should submit an e-mail with an explanation of the importance of indexing it.› The site's url was submitted to these two major search engines in Russia and was accepted by Yandex, where the site can now be easily found.

Post-production maintenance of the site includes gathering and analyzing user feedback and server logs. The e-mail received in response to the Museum of Russian Culture collections web site can be divided into four categories:

1. Acknowledgment of the historical, educational and personal value of the site:

" I will share the announcements with my mother (a Russian via Shanghai and San Francisco to Mountain View, now) and sister, who lives in Los Altos. I know we would all love to see the archives. I'll download a couple of pages for them and force them to start using the internet! You have designed a very beautiful, easy to understand and access web site." [January 10, 2002]

"Thank you for sending details of the new site, which I have browsed with great interestůand immediately found some biographical details I had been pursuing for ages. Many congratulations to all involved!" [January 10, 2002]

2. Announcements that a link to the site was added:

"Congratulations on the new "Museum of Russian Culture" websiteůlooks great. Our Center has taken steps to add a link to the site within the next few days." [December 14, 2001]

3. Suggestions to provide additional information and make changes to the text of the site and registers:

"Our visiting Russian Fulbright scholar from Vladivostok.... has been reading all the items listed in your site for days now. He says it is very good.... except....he was wondering how many reels of microfilms go with each register. Perhaps you will add that information later?" [December 17, 2001]

"Nashel neskol'ko melochey: v russkoi redakcii nomer 43 v biografii Lukashkina na vtoroi stroke "POTUPIL" Ů propusheno S Ů poStupil v institut..." (I found a few small things: in Lukashkin's Russian language biography (#43) on the second line "s" is missing in word "POTUPIL," it should read "postupil v institut." Translation by P.Ilieva) [November 14, 2001]

4. Reference questions from Russian history scholars, writers, people doing genealogical research:

"I am trying to do some research into my family history. I noticed that you possess archives of the Russian American society which apparently include papers either created by or about my great-grandfather.... See...(box1. entry 19). I am writing to ask you to provide me with further information as to what these might be. I would greatly appreciate any information you can forward" [April 29, 2002]

Reference questions have come from users in the United States, Russia, Korea, Japan, Australia, and Sweden. The overall number of reference questions related to all Russian issues, not only to the profiled collections, addressed to the project archivist and assistant archivist continues to grow.

The web site was designed and produced within four months by an assistant archivist working full time, doing all the technical work and translation; an archivist provided content and translation; and a third person proofread the Russian text. Before the official launch of the site an agreement was signed between the Museum of Russian Culture, which owns the copyright to the materials microfilmed during the project, and the Hoover Institution Archives.

Conclusion

In the fall of 2002, microfilms of the Museum's collections were sent to GARF (State Archive of the Russian Federation) and after the accession they will be available for Russian researchers and the general public in its reading room in Moscow. This means that now the Museum of Russian Culture collections web site can help remote users within Russia to locate the necessary materials before arranging their visit to Moscow. Finally, materials carefully preserved by Russian émigrés, and professionally described by American archivists, has found its audience in the historical homeland of its creators and collectors.

For more than 90 years the Hoover Institution Archives has been collecting documents in the vernacular on war, revolution and peace from different countries. Its mission and goal is to preserve these documents and to make them available to the widest possible audience. New technologies have been used to facilitate access to the collections and make finding aids and selected documents, photographs and audio/video materials available online for researchers around the world. The success of the Museum of Russian Culture collections bilingual site and the positive response it has received has inspired other, similar projects. Two new bilingual sites are now in production:

- A site profiling Czech and Slovak collections (Czech/English site) in the Hoover Archives.

- A Spanish translation of the page for the Hoover Institution Archives' Latin American holdings.

All web design, production, and translation is done in-house by the staff of the Archives. Creation of the bilingual web site not only ensures better visibility for the Hoover Archives, but also provides unlimited and unrestricted access to the wealth of its holdings for diverse audiences worldwide in their native languages.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to acknowledge the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities; the guidance of Elena S. Danielson, Director of the Hoover Institution Library and Archives, whose enthusiasm made this project possible, and the work and help of my colleague and project archivist, Anatol Shmelev.

References

Grimsted, P. K. (1993). Archival Rossica/Sovietica Abroad - Provenance or Pertinence, Bibliographic and Descriptive Needs. Cahiers du Monde Russe et Soviétique, Vol. XXXIV (3), juillet-september 1993, 431-480.

Meeting of Frontiers web site. http://international.loc.gov/intldl/mtfhtml/mfsplash.html

Popov, A.V. (2001). Foreword. In A. V. Popov (Ed.) Rossica v SSHA: 50-letiiu Bakhmetevskogo arkhiva posviashchaetsiia. Moscow: Institut voennogo i politicheskogo analiza, 4-7. (In Russian, translation from Russian: P. Ilieva).

Tibbo, H.R. and Meho, L.I. (2001). Finding Finding Aids on the World Wide Web. The American Archivist, Vol. 64 (Spring/Summer 2001), 61-77.

Vernant, Jacques (1953). The Refugee in the Post-War World. Yale University Press.