![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Archives & Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

ph: +1 416-691-2516

fx: +1 416-352-6025

info @ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search A&MI |

Join

our Mailing List.

Privacy.

published: March 2004

analytic scripts updated:

October 28, 2010

Village Voice: An Information-based Architecture for Community-centered Exhibits

Ramesh Srinivasan, Doctoral Candidate, Graduate School of Design, Harvard University, USA

Abstract

In this paper, I propose an architecture that can enable a museum to represent the material it collects in its interactions with communities. This architecture is discussed in the context of Village Voice, an interactive video browser developed as part of my M.S. research at the MIT Media Laboratory. Village Voice has shown potential as a system that can archive content generated by community members through its departure from traditional methods of using the Web to represent museum exhibits. Instead of basing content and their interrelations around ad-hoc indices, Village Voice allows the user to interact with material based on how the community itself articulates the relationships within its different pieces. I refer to this information architecture as ontology. Village Voice's interface is based around a dynamic collage which is able to reveal the complexity of the artifacts of a community because it can adapt to a user's browsing history and the intricate relationships within the different materials in the exhibit. I will discuss the means by which the system, interface, and ontology were developed, and its deployment in a Somali refugee community within the Boston metropolitan area, as well as efforts being undertaken in a North Indian village in the Faridabad, Haryana district. After presenting the architecture and project, I discuss the potential of this technology to archive and faithfully represent the experiences of communities through a simple evaluation.

Keywords: story, interactive, ontology, architecture, dynamic, collage

Alan Shaw points to the potential of communication technology to enhance community life:

If we focus our attention only on how this technology can connect us to people who are physically distant from us, then we are robbing ourselves of the potential for using these tools to address some of the most profound experiences that we will face in our lives. This is why epistemology is mightier than technology. Without adequate forethought, our technological advances can become disconnected and even contrary to some of our deepest collective assets and endeavors.Ô (Shaw, 1995, p.17)

As the museums of the future begin to close the gaps between themselves and the communities they wish to exhibit and share with the larger world, I believe their ability to access, understand, and help engage groups with which they work will become paramount.

There is a purpose behind my naming this project Village Voice. A village is a set of people who have a shared history, co-dependence, and present-day connections with those who are living in proximity to them. These links are not merely passive ties, but allow the villager to actively occupy a role within the larger community.

Village Voice is based around the decentralized navigation of narrative. In such systems, narrative unfolds based upon both what the viewer is watching and an overarching model of story.

My hypothesis is that a knowledge model, or ontology, created by community members is more than a static structure with which to represent community knowledge: When continuously populated with their stories, the ontology becomes a dynamic structure that is used by members to model the evolution of their community. Thus, ontology becomes a mechanism by which the stories and artifacts of a community can be represented and exhibited in the setting of a museum. It allows for the access and understanding of community-centered exhibits to occur through the community's own semantics. Values, discourse, and dreams are all framed in an architecture that allows for the museum to faithfully represent the evolution and experiences of communities worldwide.

Village Voice has been deployed in a community of Somali refugees based in Jamaica Plain, MA. This community has dramatically expanded over the last five years due to the civil war in Somalia. According to community members with whom I have spoken, there is a desire to archive their experiences as they face new challenges in the United States. They wish to find a means to tell stories to their community, as well as to incoming refugees and others outside of the community. Traditionally, story has been orally transmitted in Somali culture, so the use of a medium that records and retells story is new to them. In this paper, I will first share some thoughts on the role of story and the relevance of focusing on this when desiring to create a community-centered exhibit. I will discuss the methodology by which Village Voice was introduced to the Somali community and share some comments of how in general community-centered projects can be initiated. This is followed by a discussion of the ontology design process. Finally, I describe the storytelling system that was implemented and present an evaluation of the Village Voice in regard to its ability to disseminate story in the community.

Stories and Dreams

Village Voice is built upon the premise that story is fundamental to the sharing of experience. In cultures throughout the world, story exists to serve a range of purposes from teaching a moral, contemplating divinity, or preserving history. Stories are clearly one of the many ways in which we, as humans, present who we are to others (Campbell, 1988).

Human beings are storytellers by nature. In many guises as folktale legend, myth, epic, history, motion picture and television program, the story appears in every known human culture. The story is a natural package for organizing many different kinds of information. Storytelling appears to be a fundamental way of expressing ourselves and our world to others (McAdams, 1993, p.27).

Oral traditions and the role of communication technologies

Alfred Lord, whose work on oral storytelling focused on the singing bards who narrated stories to their respective cultures, explains that the oral tradition has persevered because "the picture that emerges is not really one of conflict between preserver of tradition and the creative artist; it is rather one of the preservation of tradition by the constant re-creation of it."(1960, p.29). The oral tradition has persevered through its adaptation to the change that is inevitable to all cultures.

In the Somali tradition, the oral process of storytelling is embraced. Historically, the esteemed storytelling bards of each clan transmitted this culture through poetry. Do computer networking and digital storytelling have a role in such a tradition, particularly related to the process of preserving and sharing an exhibit in a museum? I posit that while recording stories and sharing them using a computer system is a breach of Somali cultural history, it may be a productive step given the community's displacement to the United States.

The possibilities computation offers change the dynamic. Hypermedia is a paradigm that allows content to be related using pre-defined links. The interaction is discontinuous, however, because the user has to click on one of a set of choices to allow the story to continue. However, stories could take advantage of computer systems to empower the user the power to grasp linkages within the content in a more personal way. This can enable the museum to preserve and share the exhibit in a way that allows the visitor to take his or her own journey through the material that is presented.

Methodology

Originally, Village Voice was designed for the village of Tikavali, as part of the Media Lab Asia Initiative. Tikavali was chosen because of the long relationship it has had with the Jiva Institute, a NGO partner of the Media Lab Asia. The role of story in this region is undeniable. Derived from local and religious traditions, villagers in Haryana have used story to articulate their experiences, beliefs, and desires for years.

I wanted to test whether I could use a technology to mediate the common thread of story in Tikavali. For one month (Sept and Oct '01), Jiva trained villagers to use video to create stories. We collected these stories with the goal of incorporating them into a system that could represent them relative to community issues and experiences.

Figure 1: Villagers in Tikavali watching each other's stories

We collected 30 stories in this first incarnation of Village Voice, a project that is still ongoing. From the collection of these stories we found a number of common issues around which Village Voice could structure its content. In this first and ongoing attempt, I found great value in the process of engaging villagers in creating their own stories. It was clear that building a representation in community terms for these stories could be the key to building a system that could share narratives across the community.

Ontology

Ontology was found to be the missing representation, the architecture that could organize and interrelate the stories of a community in a way that was responsive and faithful to the existing social fabric.

I use Uschold's definition of ontology as an explicit representation or structure of knowledge (Uschold et al., 1995). Ontologies can be used to describe physical processes, educational fields, or in the case of Village Voice, the discourse of a community.

Ontology can also be seen as a conceptual map where the links between individual pieces of knowledge are delineated. An assumption researchers in this field make is that knowledge is without meaning unless it is contextualized. The specific nodes in the structure need to be understood along with the links that tie them together.

Roger Schank explains that through ontology, we make sense of the world. Information that we encounter is understood through our own internal "data structures", which he calls scripts. Scripts, to Schank, are our own implicit organizations of knowledge retrieved from the world we inhabit (Schank, 1999).

Joseph Novak and Albert Cañas have been responsible for some of the advances in the field of learner-created knowledge models. Their projects focus on Concept Maps (CMAP). Concept Maps are based on the idea that true learning involves the learner to construct relationships between the new information he or she acquires and that which is already possessed. The focus is to instruct the subject to explicitly map out the relationships within a certain process or object that is being studied.

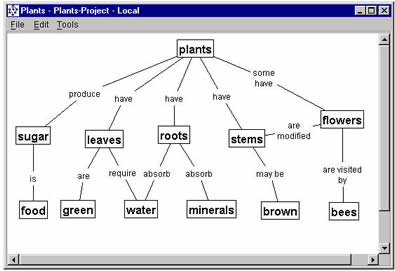

Figure 2: A concept map representation of plant (Cañas et al., 1999)

Subjects were found to have a deeper understanding of the concept of "plant" after following these steps, particularly when subjects were involved in critiquing each other's work. The experimenters argue that there are two reasons why Concept Maps augment knowledge: first, because learning is structurally organized, and second, because a general understanding of epistemology is realized by the subjects (Cañas et al., 1999).

It is this process that I have used in the development of an architecture that can represent the stories of a community. The next section of this paper reveals how.

Methodology

I needed a more immediate solution than the Tikavali project could provide in terms of distance, communicability, and community cooperation. The creation of the ontology would be the output of a significant amount of fieldwork, rapport building, and patience in my introduction of the project. I would need to work with a local community that I could visit repeatedly, teach a number of video story classes with, and work iteratively to elicit an evolving ontology. With this in mind, I sought out the Somali Development Center (SDC) in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts. In the next two sections, I briefly introduce Somalis and their ancestral culture, and the community in Jamaica Plain. In the meantime, the project in India proceeds, but to really establish this ontology-based architecture, I focused on this local community.

The Somali refugee community in the Boston area is concentrated amongst a few pockets in Jamaica Plain, Roxbury, Revere, and Charlestown. The population of this group has expanded over the last five years from about 3000 to 5000 (Yussuf, 2001). Refugees span a variety of ages; however, because of the mercurial nature of some of the programs that brought Somalis to Boston, a number of families have been broken up in the process. Refugees today are victims of a civil war that has torn apart these families and decimated a once thriving culture.

There are only a few major hubs around which Somalis traditionally gather. Most important seems to be the Somali Development Center (SDC), on 205 Green St. in Jamaica Plain. Since 1996, the SDC has been a hub for educational and social services for the growing Somali community in Boston. SDC was established and funded by a small group of Somali-Americans who originally came to the United States to obtain higher education.

I introduced myself to the community as a graduate student at MIT interested in using video to document the experiences of people in the community with the purpose of creating an exhibit that could serve as a growing archive of their shared issues, challenges, and experiences as recent immigrants to Boston.

The project was well received from the start. There were obvious needs that this project could fill for the SDC. Most important among them was the situation with incoming refugees. One of the priorities of the SDC is to work to integrate these people with the existing Somali community, and ultimately with the basics of living in Boston. A technology that could introduce new members to issues and associated stories of the community would help the process of acclimation. In addition, building a tool that could document the unique culture of Somali-Americans could help future generations be connected to their traditions, and reflect on how they have changed over time. Finally, the SDC was interested in using the different video stories gathered by project to present thematic programs on their weekly cable access television show in the area. While not as interactive as using the technology, this would certainly release the stories of the community based on the themes specified within the ontology.

A variety of SDC members had indicated to me that the Center faced some significant problems. For example, the clan heritage with which many Somalis identify has been a significant stumbling block in the Center's efforts to try to build a unified community that can benefit from the programs it offers. Is it possible to use technology to remind Somalis of this heritage yet still show that these refugees are one clan, together living in Boston? And where does the role of the museum come in here? How can an institution that has a community-centered exhibit help the community yet powerfully represent its stories to the outside world?

I became involved with the community first as a tutor and mentor for teenagers. This involved bi-weekly visits to the Community Center and other Somali institutions, where I would work on different subjects with these kids. After two introductory months, it became clear that I needed to involve members of the community to lead the project. This would allow the project and its purpose to be better communicated to the entire community, while facilitating the search for potential story creators. I began to introduce the project to the kids I was tutoring, to elders in the citizenship classes, at the local high school (English High School) where the Somali teenagers of the area went to school, and via the weekly cable-access television show.

It took a short while, but the efforts paid off. I soon met many prospective story creators. After an introductory workshop on the basics of creating video, I gave very few instructions to participants except to focus their stories on issues that are relevant to them as Somali immigrants in Boston. Over a month, 50 stories were collected from the seven story creators.

I wished to use these stories to stimulate the design of a representation, or ontology, that could illustrate the intersecting issues of the community. My goal was to engage the community in the reflective process of creating an ontology that could articulate the relationships between relevant community issues. As issues in the community would change, the community could redesign this representation through future ontology design meetings.

Here I present the process and result of our initial community ontology design:

Date of workshop

Thursday, April 11, 2002

Background

50 stories created by community members were collected and uploaded to the Village Voice system in Quicktime 5.0 Format. I converted these stories to a VHS tape for the meeting because the SDC lacks the computer resources to access the Village Voice site. The story creators had created approximately two hours of video footage by this point.

Presentation

We divided the workshop into two sessions, both of which were attended by many of the same participants. The first presentation took place in the morning after the citizenship class, and the second took place during the traditional tutoring sessions, after school for some of the younger participants. The two sessions went from 11 AM – 1 PM and 2:15 – 5:00 PM. Each session had about 20-30 participants.

Setup

Approximately 80% of the videos were in Somali, and had only been roughly translated for me. Many of the participants, particularly older members, did not speak any English as well. For these reasons, two leaders of the SDC helped me lead the workshop. They were Abdi Yussuf, current director of the SDC, and Abdul Hussein, the founder of the SDC and owner of Sagal Caf and Enterprises.

Goal Explanation

Abdi and Abdul asked me to give them some examples of ontology so they could explain it to the community. I concluded on an approach of explanation through example. I showed them a variety of different ontology projects. Abdi and Abdul concluded that they would explain the ontology to the participants by asking them to discuss community priorities and the relationship between these.

Stories, Reflection, and Decision-making

Each session began with an explanation in Somali to remind participants about the purpose of the project. The movies were then shown on VHS tape, and participants were encouraged to pause, stop, or repeat the video at any time. They were instructed to do this whenever they felt an issue that was relevant for their community was revealed in a story. During the pauses, the community would discuss the videos they were watching and craft a part of the ontology diagram on the white board in the front of the classroom. The question of following tradition versus adaptation to being in America dominated the discussions participants had during the workshop. Elders would express consternation over the direction their kids had taken. One female elder implored, "These kids don't have the respect for authority we did at their age. Look at the language they use. What has happened to what the Koran has taught them?" Some teenagers, on the other hand, while remaining quiet when elders were in the room, would tell me that while they had great pride in their heritage and religion, they felt a need to fit in with their peers at school, and to follow the opportunities being in America has allowed them.

Particularly spirited arguments came up when movies related to women and sexuality or generational issues were viewed. Even the older and deeply religious participants, were very divided on the question of female circumcision, which is performed on approximately 98% of Somali girls. Some participants argued that their move to a more democratic and diverse country should force them to reconsider such practices, which cause health problems and are invasive to women. Others, however, said that rejecting these traditions was insulting to their Somali Islamic heritage.

During these discussions, the community would come to a consensus on whether an issue that had come up should be included in the ontology. For example, one story was set at a Somali youth party. It showed teenage men and women dancing together to hip hop music. The idea of a youth dance party without Somali music was disagreeable to some of the participants because of its disrespect to the Islamic taboo of pre-marital relationships, while most of the youth at the meeting argued that one could have a pre-marital relationship without being disrespectful to Muslim culture. During this discussion, the participants decided that issues of religious tradition, sexuality, and generational differences were relevant to the ontology. These topics were then added to the ontology and linked to each other on the white board.

The process of using these stories to allow the viewers to articulate their opinions ended up being the key to the design of the ontology that emerged. The fact that certain issues raised such discussion brought to light how relevant they were to the overall community, and allowed community members to flag them as relevant to include in the ontology. Over the course of the meeting, we went through several iterations, as different participants offered input and sketched the consensus of issues on the whiteboard. The drawn structure changed multiple times in the process, as the community members reflected further on the issues that united them.

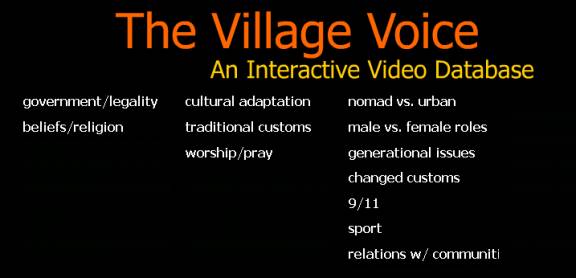

The structure that emerged from the design meeting is the following:

Figure 3: Somali Community Ontology

Every community issue listed in the above diagram is called a "node" in this thesis. The above ontology is a tree-like structure, where all nodes are considered a "part-of" the parent to which they are directly linked. The question I next faced was related to integrating this ontology into the Village Voice.

Before discussing the interface, I explain the process by which stories are associated with the community ontology.

I instructed the story creators with the basics of iMovie. As digital videocassettes were brought to me for submission, the story creators would use the editing software to extract stories from the cassettes and convert them to the Quicktime 4.0 format. The story creators were then instructed to annotate these stories according to the ontology, using the story "upload" page.

Figure 4: The Somali community reacting to the video stories

The story creators can decide to annotate their stories with as many of the ontology nodes as they wish. These annotations determine the association between the story and the ontology.

Village Voice has been made publicly available on the Web (http://village-voice.media.mit.edu). As stories are submitted from the upload page, they are included in the database.

Interface

Figure 5: Village Voice Search Page.

This page shows one major branch of the community-created ontology. Village Voice is entered via a "search" page. This page is organized hierarchically, according to the tree-based design of the ontology. The user can select multiple nodes from the tree that he or she is interested in watching stories about.

There are two colors of text on this page: white and yellow. The yellow text (at the bottom of the page) reflects the nodes that the user has selected to browse stories on. Above these are citizenship, refugee flight, and sexuality/relationships. The white text (in the center of the page) reflects the ontology tree, from which the user can select an additional node to browse on by clicking on it. Finally, the user needs to click on the search button to reach the browsing page, which expresses the relevance of stories in the system to the topics chosen by the user.

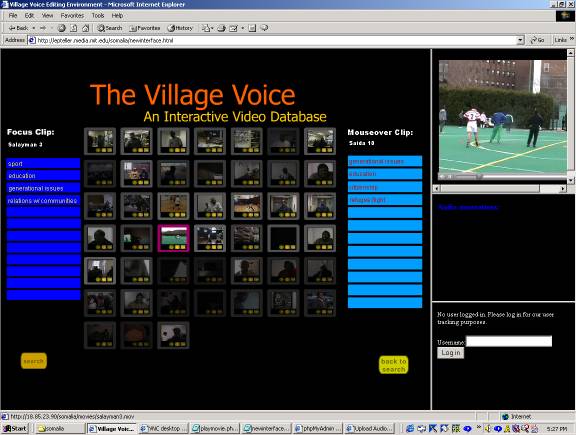

Figure 6: Browsing collage page

The browsing page is designed to give the user a wide range of information about the different video stories by displaying each story's thumbnails, while conveying their relationships to each other.

As seen in Figure 7 below, the thumbnails are illuminated to varying levels. This is reflective of how closely each thumbnail corresponds to the terms the user decided to search on in the search page. A brighter illumination indicates a closer match with the search query.

Figure 7: The focus story and its relationship to the collage. The selected story is highlighted in pink, and the other stories in the collage are shownwith different levels of illumination depending on their similarity to the focus story.

The story that best matches the query is known is the focus story, whose thumbnail has a pink-colored border. Once the browser is loaded, a user can change the focus story by clicking on any other thumbnail in the collage. This changes the illumination of all the other thumbnails in the interface based on how closely their annotations match those of the new focus story.

The user is now presented with a number of options.

Thumbnail Options

Figure 8: Story thumbnail.

The three buttons on this thumbnail (from left to right) allow the user to stream the video story, view all its audio annotations, and upload an audio annotation of his or her own.

The story can be played by selecting the play button, which is the leftmost of the three buttons below the thumbnail. This will stream the video in a frame to the right of the collage.

Users can also record their reactions to any story that they view. These reactions can be uploaded as audio file to Village Voice by selecting the Talk button below the thumbnail. This will open a page, as shown in Figure 9.

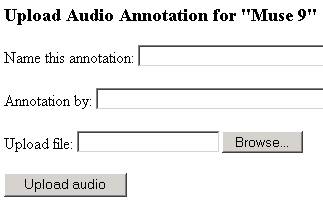

Figure 9: Audio upload page. This page appears when the upload audio annotation button is selected

Finally, the user can listen to the audio annotations associated with any story. These can be loaded by clicking on the middle of the three buttons under the thumbnail.

Searching on Ontology Nodes

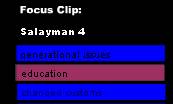

Figure 10: Focus story annotations according to the nodes of the ontology. This box is shown to the left of the browsing collage

The user can concentrate the browsing collage to focus on a subset of the nodes of the ontology that the focus story has been annotated with. This is done by selecting any number of nodes from the focus story annotation box, which is found directly to the left of the browsing collage.

At any time, the user can leave the browsing page to go back to the search page by clicking on the "back to search" button on the bottom-right of the page.

Clustering Algorithm

Village Voice finds stories that "best" match a user's search queries or browsing choices based on its clustering algorithm. The level to which a story matches the browsing choices is revealed in its level of illumination, or alpha value. Alpha values range between 0 and 1, and are directly proportional to the score calculated below.

In this algorithm, I introduce the terms "branch nodes" and "end nodes". A story's end nodes are the ontology nodes with which it is explicitly annotated. A story's branch nodes, however, are not only the nodes with which it is annotated, but all the nodes on that story's branch of the ontology tree. For example, if a story is annotated with the nodes "Nomad vs. Urban" and "9/11", its end nodes would be the two nodes, but its branch nodes would also include their mutual parent, "Cultural Adapation".

Evaluation

Now that both the methodology and interface for this community-centered story archive have been discussed, I would like to point to a simple experiment that demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach for the museums of the future. I believe that the effective exhibit must show a greater level of engagement with the community, and thus I wanted to study how strong a representation of the community the village voice approach was.

I designed an experiment to test Village Voice's use of ontology versus a keyword-based representation (Salton, 1968). In the keyword version, I selected the five most frequently spoken words in each story, and annotated each of the stories in the system with these. The keywords were identified by the story-creators, who kept a histogram of the words that were spoken in their stories and gave me a list for each story. This list did not include "noise" words such as "is" or "and", which are without significant meaning. Because most of the stories were in Somali, the community's input was critical in creating the control for this experiment. We also translated Village Voice into Somali so all the conditions would be replicated.

As in Village Voice, in the keyword version, words can be selected as the basis for story search. Browsing is also possible in the same way. The only difference is that this version groups stories based on whether the story is annotated with the same keywords. No clustering is done based on relationships within the ontology, which is the key difference.

Over one week of testing, 30 subjects were tested, all of whom were Somali immigrants living in the Boston area. I asked each subject to sign an informed consent form, which assured them that the study was anonymous.

Each subject was asked to browse Village Voice and the keyword version for as much time as they wished, with a minimum of three minutes. Before using either version, the subject would log in to the system with an anonymous name so that I could monitor which sequences of stories the subject browsed, how long he or she stayed logged on, and how many stories were played. The audio annotation feature of the system was not completed when testing was conducted, so this was not measured. My results were as follows:

This data shows the mean and standard deviation values (across the 30 subjects) of the number of stories browsed, number of stories played, and time online for the keyword (KW) and Village Voice (VV) versions. The values for time online are expressed in terms of seconds.

| Mean value | standard of deviation | |

| KW time online | 263 | 205.36 |

| VV time online | 967 | 891.39 |

| KW # clips browsed | 2 | 0.697 |

| VV # clips browsed | 7 | 2.719 |

| KW # clips played | 1 | 0.433 |

| VV # clips played | 3 | 0.788 |

Table 1

These data show a higher engagement for subjects across-the-board with Village Voice. In general, subjects spent a lot of time studying the interface and not interacting with it heavily, as can be seen by the rather small number of clips played or browsed on in either version. Many subjects mentioned to me that they would have browsed in more detail if they were more used to the system and technology, in general.

I present the story of one subject who browsed the system for 10 minutes. This subject was first exposed to the keyword version, where he spent his time selecting words from its search page viewing the browsing collage and then going back to the search page. In the approximately 3 minutes that the subject used the keyword version, only once was a clip played, and no browsing was done from the browsing collage itself. The ontology version shows a different behaviour. Seven stories were played, and the data show that the subject clicked on multiple thumbnails on the browsing collage. Overall, the subject was measured as being more engaged over the three data variables of the study. It appears that the ontology version inspires more browsing activity from the browsing collage page, and that the clustering of stories in Village Voice enables subjects to perceive more connections between stories.

Concluding Thoughts

I have observed that ontology can become a dynamic structure that can model a community, and that it can encourage individuals to frame their experiences in terms of relevant community themes. Testing has shown it to be a model that can allow stories to be disseminated more effectively than the traditional index of keywords that are spoken. As the community changes over time, it can use ontology to contemplate where it has been, and where it is heading. This points to the potential of the Village Voice model as a means to dynamically exhibit the experiences of a community. Basing the unfolding of these narratives around the community ontology opens up the possibility for them to be disseminated more effectively than the traditional index of keywords that are spoken.

Significant amounts of research remain to be done to better understand how to maintain dynamic models of communities. However, this approach has allowed a community to take control over the means by which it is exhibited to the public, yet use the exhibition as a means of reflection. I believe that approaches such as this thold promise in future intersections between the museum and community.

Acknowledgements

This paper was prepared with guidance from Jeffrey Huang – Assistant Professor: Graduate School of Design, Harvard University, USA.

Bibliography

Campbell, J. (1988). The Power Of Myth. New York, NY. Doubleday.

Cañas, A. & Joseph Novak (1999). "Using Concept Maps with Technology to Enhance Collaborative Learning in Latin America", accepted for publication, Science Teacher.

Lord, Alfred (1960). The singer of tales. New York, NY. Atheneum Press.

McAdams, Dan (1993) The Stories We Live By. New York, NY. William Morrow And Company. Inc.

Salton, Gerard (1968). Automatic information organization and retrieval. New York, NY. McGraw-Hill.

Schank, Roger (1992). Agents in the Story Archive. Institute for Learning Sciences, Northwestern University.

Shaw, Alan (1995). Social Constructionism and the Inner City: Designing Environments for Social Development and Urban Renewal. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Dept of Architecture. Program in Media Arts and Sciences.

Uschold, Mike (1996). Building Ontologies: Towards a Unified Methodology. Proceedings; Expert Systems '96 conference