![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Archives & Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

ph: +1 416-691-2516

fx: +1 416-352-6025

info @ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search A&MI |

Join

our Mailing List.

Privacy.

published: March 2004

analytic scripts updated:

October 28, 2010

Are Art Museums Serving Our Targeted Audiences?

Holly Rarick Witchey, Cleveland Museum of Art, USA

Abstract

Children & teenagers, 18-35 year olds, minorities, the disabled—every group on this list is considered an important audience by art museums. What are we doing to serve them? What benefits have accrued after years of educational and cognitive theory and with the advent of new tools and technologies? Art museums have reached all new highs (and lows) in their approaches to underserved communities. This paper looks beyond our best intentions to actual outcomes. What does the content we choose to display on the web reveal about our commitment to certain audiences? How do special audiences discern the differences between commitment and special-project pandering? Have we failed audiences by judging our best efforts according to low standards? Few art museums have the money, staff, skill-sets to serve all these special targeted audiences effectively. What best practices guidelines exist outside of the museum field for serving children, minorities, and the disabled on the web? Improved content, decreased legal liability, greater audience reach—these are just a few of the benefits that result when our web sites are made more accessible. This paper charts where art museums have been and where they are going in terms of four targeted audiences: children, minorities, and the disabled.

Keywords: Education, children, accessibility, minorities, disabled, African-American, audiences

Are Art Museums Serving Our Targeted Audiences

Which Came First: Changing Technologies? Changing Audiences?

In 1996 the California Governor's Conference on the Arts and Technologies hosted a panel discussion entitled "Virtual Museums—Companions or Competitors." Argument was running fast and furious against the idea of virtual museums—how they would destroy attendance at traditional museums, how virtual presences were a waste of time and money, how they would breed a future population with even less understanding of art than currently.

At this point, Ken Hamma got up to speak. Ken is currently Assistant Director of the J. Paul Getty Museum in charge of Information Technology. In 1996, however, he was the Associate Curator of Ancient Art at the Getty and just beginning the transition from curator to technologist. He gave an inspirational talk on the history of the rejection of new technologies as a typical manifestation of the normal fear of change. For those of you who were not at the conference, I include a portion of his comments here, reproduced with his permission.

I am here representing to some small extent the point of view of a traditional museum where real not virtual (as we understand that today) objects predominate, where ineffable qualities of the physical thing-in-itself are highly valued

To hold and preserve these things for the sake of our own memory is a fundamental cultural necessity. In this perspective there is no reason to discriminate against one medium of interpretation and presentation because it poses new difficulties (digital delivery and virtual reality) and new opportunities (digital delivery and virtual reality, again). If we can remain focused on mission we should be able to calmly ask ourselves "Does this help us do what we want to do and more or less have always wanted to do?" And we will probably find that the answer eventually is, yes it does, but in ways we can only begin to imagine today.

That was 1996; this is now. The question he poses remains the third most important question responsible museum professionals can ask, "Does this help us do what we want to do and more or less have always wanted to do?" The first two questions ought to be "What do we want to do?" and "Why do we want to do it?" Perhaps these questions seem obvious but as funding gets tighter museums are more and more increasingly motivated by practical questions like "I found this great grant opportunity, what kind of projects can we think up to get this grant and make sure we have jobs for the next six months or two years?" Museums in general, and art museums in particular, seem to be moving farther and farther away from first principles as established in mission statements.

While most museums no longer fear new technologies, they are slow to embrace all the opportunities offered by new technologies. With regard to our web sites, our goals are either impossibly broad or ridiculously modest These goals are based on any number of factors including: available resources, the perceived utility or non-utility of web sites in general by administration, and the status of employees working on the web, either within the museum structure or as outside contractors. Hovering nebulously in the either and haunting us in the belief that—given the potential of the web—there ought to be a way to please and attend to the needs of all of our audiences.

Museums are facing tremendous budget cuts. Developers observe an ever-dwindling pool of clients with less money than before. Everyone is being held more strictly accountable and the need to focus on strictly mission critical projects is already close at hand. After several good years, the new, leaner, Post-September 11 years are hard-going. Many of us may well not be in the same job, or even the same field, two years from now. Many jobs that currently exist will cease to exist.

I would like to suggest in this paper that now, more than ever, art museums need to take a more serious look at the audiences we serve and decide who we can best serve and how we can best serve them. It is probably possible to serve everyone, but it is surely impossible to serve everyone well. For those of us in charge of web sites it is time to acknowledge and be more proactive about serving targeted audiences—something the web can do quite effectively. Four audiences seem to be of particular interest to art museums: children (of all ages), the much-desired 18-35 demographic (representing the promise of a future for non-profits), minorities, and individuals with disabilities. This paper will look in-depth at only one of these audiences, children.

For years new technologies have been touted as the way to enlist the interest of new/changing audiences. Art museums have clearly bought into the need to incorporate new technologies into their arsenal of interpretive devices—witness the plethora of sound and audio guides, hand-helds, interactives, and Web sites that have multiplied in the decade. In difficult financial times it is hard to predict if museums will continue to invest in technologies unless they can prove that the content is important, relevant, and necessary to their audiences. And the four audiences designated in the above paragraph account for a tremendous amount of cultural and economic clout.

This paper looks beyond our best intentions to actual outcomes. What does the content we choose to display on the web reveal about our commitment to certain audiences? How do special audiences discern the differences between commitment and special-project pandering? Have we failed audiences by judging our best efforts according to low standards? Improved content, decreased legal liability, greater audience reach—these are just a few of the benefits that result when our web sites are made more accessible. This paper looks at where art museums are and where they seem to be going, web wise, in terms of a major targeted audience: children. What are art museums doing to make a difference? What can they do to make a difference?

Targeted Audiences

This paper is an offshoot of a review of important issues surrounding the existence and development of new media in museums in the last decade. Presented in Toronto at the annual meeting of the Museum Computer Network in the Fall of 2002 (Witchey, Whither New Media, MCN 2002), audience response to the targeted audience section of the paper—particularly the discussion of children-- caused the most comment and this paper goes into greater detail on that issue.

Audience development—an important topic for museums—if it weren't there wouldn't be so many sessions on children's education, distance learning, lifelong learning, interactivity, accessibility, survey software, newsletters. Everyone talks about special audiences, but how are museums specifically using their web sites to reach out to these audiences?

The Cleveland Museum of Art began looking at this topic during a private exercise to benchmark our museum against museums of similar size, collections and resources as well as a few museums in our local region. This exercise of looking at our peers has occurred in stages, as new features were developed for the CMA Web site (www.clevelandart.org). In the last quarter of 2002 and the beginning of 2003 the benchmarking group was enlarged slightly and targeted for an informal user review. Matthew Asti, a student at Oberlin College, help was critical in gathering data his work is incorporated into this paper.

-

the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY (http://www.metmuseum.org);

-

the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (http://www.nga.gov)

-

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA (http://www.mfa.org/home.htm)

-

the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA (http://www.philamuseum.org

-

the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL (http://www.artic.edu/aic/)

-

and the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA http://www.getty.edu).

-

and the L.A. County Museum; Los Angeles, CA (http://www.lacma.org/).

In terms of regional museums, we looked at the web sites for

-

The Detroit Institute of Art, Detroit, MI (http://www.dia.org)

-

the Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, OH (http://www.toledomuseum.org/home.html)

- the Minneapolis Museum of Art, Minneapolis, MN (http://www.artsmia.org),

although Minneapolis, because of its size and level of activity in this field really place it in both categories.

It goes without saying that many other museums in the United States and internationally are doing projects targeting these audiences, but we had to start somewhere. Colleagues across the country are doing interesting projects but did not have the right benchmarking characteristics for this review.

One last caveat—we may well have missed something on a web site, something wild and wonderful, however if we missed it and we were consciously looking for it, what are the chances that your targeted audience will find it?

The Good News: Resources for Students K-12, What Adults See

The good news: there are some excellent K-12 resources out there. Predictably all of the museums in our group listed activities for the K-12 audiences on their websites. Most of these listings relate to programs that occur within the actual physical confines of the museum. Large museums have a significant number of online activities with our colleagues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art leading the way. The Minneapolis Institute of Art has extensive online activities and—what's most impressive—some of them are geared to high school age students and not just the coloring book set.

Cleveland has an online space for children but most of the activities need to be downloaded and printed and are not interactive in the more exciting sense. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the J. Paul Getty Museum did not dedicate any part of their web site specifically to children's online activities, but in some cases, specifically the Getty, these are in the works. In terms of the Midwest, The Detroit Institute of Art had a few children-related activities but they were difficult to find. [Everything Between Earth and Sky: Student Writings About Art, Detroit Institute of Arts, http://www.dia.org/studentwriting/pages/poems.html] and we could find nothing at all on the Toldeo Museum of Art's site.

Art museums have been a little lazy in terms of development. Run-of-the-mill online items embraced by museums seem to fall into three categories: coloring books (print out), detail treasure hunts (find the detail in the larger picture), and concentration games. Though not entirely static, these online items are primarily web extensions of techniques museums have embraced for years to engage children. While momentarily engaging, their long-term educational value is debatable. The web effectiveness of these devices is surely more dependent on the content than on the device and, in some cases, on the fact that there is just not an over-whelming amount of interesting content for kids on art museum web sites. What is interesting, pales in comparison to the flashy animations and shallow activities offered by the commercial sites for kids: www.candystand.com, www.shockwave.com, www.zoogdisney.com, www.nickelodean.com; www.cartoonnetwork.com; www.divastars.com; www.lego.com.

In general, art museums aren't thinking about children as a major audience, if we did, we'd have something for them on our homepage. We apparently don't expect them to arrive and navigate within our museum site any more than we expect them to get into cars and drive to our physical facilities. The National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. has a graphic link for children on their homepage "NGAkids (See Figure 1This is the exception rather than the rule for art museums. In the other sites kids activities were embedded, either in education, or in another portion of the site, although the Art Institute of Chicago has a text link at the bottom of their home page "kids and families.").

Figure 1: The National Gallery of Art, Homepage, http://www.nga.gov/

The National Gallery's prominent labeling is clearly a plus for parents, teachers, and students—particularly the latter who have little patience for wading through wordy or static graphic pages. To be fair, art museums aren't making their physical front entrances any more fun either—the difference is, museum's could easily provide enticing child-friendly portals for their information, or at least a cheerful graphic on the homepage.

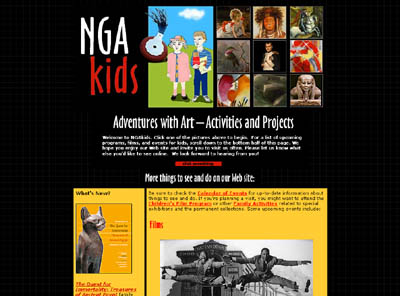

When you do click thru to NGA Kids there are a series of thumbnails of artworks and the activities are all based on the thumbnails but not listed. The activity a child chooses is determined by their aesthetic preference rather than a verbal description f what they are going to get when they click through.

Figure 2: The National Gallery of Art, NGA Kids, http://www.nga.gov/kids/kids.htm

In addition, all links within NGA activities were pop-up windows so the activity was not completely interrupted. A particularly fine activity was organized around their Martin Johnson Heade, Cattleya Orchid and Three Brazilian Hummingbirds.[http://www.nga.gov/kids/heade/heade1.html] This exploration leads a young student through active looking and association exercises, including sound, and ends with a word search that can be—with difficulty—accomplished online or printed out.

As might be expected, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has several activities directed towards children. Their Timeline of Art History is well laid, out, sometimes sparse on information, but with the potential to be scalable. The Timeline also takes advantage of the idiom of the internet so a visitor can navigate chronologically or geographically and not just linearly. In terms of diverse content, the timeline is highly concentrated on European and Asian objects with rather less attention paid to Africa and Asia. The potential is there to create an even more outstanding resource than already exists.

Figure 3: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Timeline of Art History, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/splash.htm?HomePageLink=toah_l

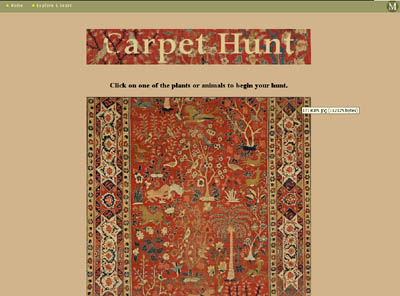

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is good at balancing being interactive with encouraging good looking habits and active viewing as opposed to passive dispersal of information. An example is the Met's Carpet Hunt. Click on a detail and you are asked a question that encourages you too look at it and then leads you to another part of the picture, thus helping the visitor create a narrative.

Figure 4: Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Carpet Hunt, http://www.metmuseum.org/explore/flowers/flowers/index.htm

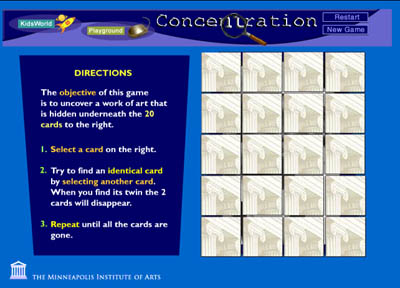

Many museum sites have generic games that art content is grafted onto, momentarily interesting perhaps but ultimately pointless (concentration games frequently fall into this category).

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts is clearly the most innovative, experimental, and ambitious institution in the group we looked at. "The Playground" which is part of the ArtsConnected project and is joint project with the Walker Art Center has a wide range of projects for students of all ages broken up into the categories of "Make It," "Find It," "Explore It," "Watch and Listen."

Figure 5: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, "The Playground,"http://www.artsconnected.org/playground/index.shtml].

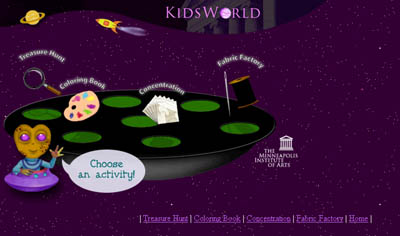

MIA's "KidsWorld" portal to activities for smaller children features requires some finding. To get to this from the home page you need to search or know to choose "Interactive Media." Once there though, children see a kindly alien creature in a small space ship. Children can choose from the traditional art museum activities for kids: treasure hunt, concentration, and coloring book.

Figure 6: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, "KidsWorld", http://www.artsmia.org/kidsworld

The activity "Fabric Factory" gave a textile twist to normal online coloring books by allowing children to fill in images with a pre-set selection of stitches, instead of simply colors.

Figure 7: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, "Fabric Factory", http://www.artsmia.org/playground/fabric_factory/game.html

Their approach to "Concentration" is, again from a grown-up's point of view, innovative. In order to reveal the art work underneath, children must match descriptive statements about the work they are going to see.

Figure 8: Minneapolis Institute of Arts, http://www.artsmia.org/playground/concentration/random.cfm

Minneapolis, as many of us know, has traditionally been a leader in this area. Blessed with the talents of the Interactive Media Group and consistently well-funded, their projects consistently display careful attention paid to interaction, graphics, and content.

Targeted content for children is out there, but you have to look for it. Art museums, in general, are not willing to compromise that "stately pleasure palace" home page by littering it with an icon that would be attractive to younger audiences. Perhaps this is not as important as it might seem. What all these successful projects do have going for them is tie-in to curricula—whether general or specific. As long as an activity is tied to a lesson plan, or a lesson plan can be built around it—the interpreters (teachers, family, adult friends, community groups) will find it. But what do the young audiences themselves think of all this content?

The Bad News: What the Children Say and Do

"Where are the games?"--6 year old, male, about CMA website"I hate stupid characters."--9 year old, female, about Rosetta Stone on CMA web site"This is too much like school."--13 year old female, about student activity on Met web site"Puzzles and concentration games are boring unless you can instant message while you play."--9 year old male, about concentration on MIA site"It's not even close to exciting, the flowers are nice.."--10 year old female, about Metropolitan "Carpet Hunt"

In 1560, the Netherlandish artist Pieter Bruegel painted Childrens Game. A seemingly endless hoard of children swarms across the large surface of this painting, mimicking the faults, habits, and quirks of their elders. For Bruegel children represented the human condition and he was trying to point out to his adult viewers that, like children, we jump, run, play, and follow our own foolish inclinations.

At professional conferences (MW, EVA, MCN, ICHIM, AAM) we talk the talk about educational programming and projects for children online, but we don't seem to listen much to children. Because so many of the projects we create are so much better than anything we had as children, we think today's children—given a few extra bells and whistles—ought to be impressed with our efforts. Children are born critics and we are surprised when they criticize, or worse yet, pay no attention at all to our best efforts. Furthermore, today's children are also canny consumers of what the internet offers and they do not spend much time or effort on activities or sites that bore them.

My own son, Nicholas, is 9 years old. When he was four we took him to Sea World. The big event was, of course, to end up at the Shamu extravaganza. When we were finally seated and the show had begun, I noticed that Nicholas was not watching the gigantic aquatic mammal 20 feet in front of him; he was concentrating on the even more gigantic screens behind Shamu televising whale's every move in triplicate behind the real thing. This event has been eating at me for five years and finally, as I began to think about this research last year, I brought this event to my son's notice. His 9 year old reply, "What's the big deal, Mom, one's dots and one's not." That is a wake-up call. Their reality is not our reality.

The vast majority of children are reluctant visitors to museums and museum web sites. Few children choose, on their own initiative to visit either a museum or a museum web site. When they come to a physical museum, they come with interpreters (teachers, parents, guardians, friends, community groups). Someone has made the decision that it is important for the child to visit. Web visits have generally the same conditions behind them—children have been directed to visit or have been given a topic that ultimately leads them to a museum site.

To try to woo this crowd with their own vocabulary is a recipe for disaster. Art museums, in general, don't have the time, money, resources, or inclination to do this. It would be foolish of us to try and fight Disney or the Cartoon Network on their own terms—they have their demographic targeted, mapped, and dancing to whatever tune-of-the-day they desire. One of my original goals in writing this paper was to illustrate to museum professionals exactly where kids are going, and even as I write this paper, my information on current trends is quickly creeping out of date. A few examples should suffice:

My daughter (6) likes websites that have lots of brand name recognition. www.foxkids.com is today's favorite mostly because of the funky music that loads even before the images are up. She then makes a bee-line for the Digimon games. www.nickjr.com for Sponge Bob games, www.harrypotter.com for Quidditch practice game, www.barbie.com for pet care and music making games. She will also explore links to sister sites, if the graphics are interesting enough. That's how she got to www.divastars.com --from Barbie. We don't have cable so she does not spend a lot of time in front of the TV at home but I guess those are the things kids talk about at school. (32 year old mother of three)9 year old male, likes to play games online, primarily at www.zoogdisney.com9 year old male & 10 year old female, together they started off at www.zoogdisney.com catching up on the Lizzie McGuire site and making the characters dance http://www.disney.go.com/disneychannel/lizziemcguire/index_main.html and then onto the Kim Possible site http://www.disney.go.com/disneychannel/kimpossible/index_main.html, where they went on a shopping mission to find the right clothes to wear before heading off to www.ikea.com and www.potterybarn.com to view furniture.Two males, 11 & 8—they like to work together on the web at www.sikids.com fantasy footballs, stats, etc what more could a boy ask for! Also Internet is research tool for Playstation games walkthroughs. Also they participate in online gaming (i.e. Blizzard's Battlenet http://www.battle.net/) to play games and connect with kids in the outside world.Four males, all 11—they like to go to www.shockwave.com and www.candystand.com. At shockwave they play games, primarily delirium and Tamale Loco.Five females, 10 & 11—they like to go to www.candystand.com and play miniature golf or to go to ikea.com or potterybarn.com to shop.

Pre-Teens & Teenagers

Two females, 12—like to go to Sims Online and play Hotdate. http://www.ea.com/eagames/official/thesimsonline/home/index.jsp?13 year old female, serious athlete, doesn't spend much time on the internet.First thing she does is check e-mail, and has just gotten an instant messenger account set up. She said she would most likely be looking for music downloads while chatting with friends. Still likes to play some games, but couldn't (or wouldn't) name any specific sites.

With the exception of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, museums are seldom brave enough or fool hardy enough to try to woo the teenager. This is as it should be because neither the museum nor the museum web site is the natural habitat for the typical teenager—except for the rare few who are headed for careers in the field. They come into the museum accompanied by adults, primarily on school field trips, and are set free to explore—sometimes with targeted activities to provide structure, sometimes not.

In school, they are directed to museum web sites to do research or write papers. They participate in distance learning projects or in special groups as museum ambassadors. They build content sights about art and around art but it is neither museum nor web site is a typical first choice entertainment. The challenge of art museum programming—web or otherwise—for children and teenagers is to provide both a relaxed learning experience and a social experience.

More than twenty years ago the Brooklyn Museum sent a questionnaire to 520 teenagers, and interviewed a Peer Advisory Council of 12 high school students. Despite the age of the survey, and given that priorities of students may have changed slightly, the results of the survey are well worth repeating. The teens top three priorities were: good grades, good jobs, and socializing with friends. Three additional items also seem warranted for inclusion in the discussion.

Data revealed that teens' negative attitudes about museums stemmed from past unhappy experiences with museum staff, coupled with the perception that their ideas would not be taken seriously.

Despite their interest in creating personal collections of objects, the students were not able to see museums' collections as sources of wonder and knowledge about human creativity.

They thought of museum objects in purely functional terms.

The conclusion: museums are only tangentially and occasionally relevant to teenagers.

Conclusions

Art museums have ever been aware that children are one of their most important audiences. So, to return to questions posed at the beginning of this paper.

What do art museums want to do? Educate children about art.

Why do art museums want to do that? Because, the staff at art museums believe that art enriches lives and children who understand and appreciate art have better lives.

Can web features targeted at children and teenagers help us do what we want to do and more or less have always wanted to do? The answer must be a resounding YES.

Today's audience—particularly children and teenagers are used to technology and expect interactivity. They don't want to be spoon fed information—they want to be spoon fed candy-coated bits of information from which they can choose the bits they are interested in and create their own meaning, not have it created for them. This situation poses two more questions that art museums are struggling with: Who creates meaning and how do we in art museums interpret this issue and provide a real venue for education?

Art Museums can best serve targeted audiences of children and get the biggest return on their investment by working with the interpreters (teachers, parents, guardians, community groups) to provide information on relevant topics: art, art history, culture, social issues in art, language. And, when applicable, to gather and disseminate viewpoints and perspectives in addition to those traditionally put forth by the museum. An art museum web site is the ideal mechanism for connecting with children before, during, after, or—when an actual visit is impossible—in place of the physical visit. To quote Ken Hamma, once again:

there is no reason to discriminate against one medium of interpretation and presentation because it poses new difficulties (digital delivery and virtual reality) and new opportunities (digital delivery and virtual reality, again).

Art Museums need to expand any opportunities they have to reach children via the WWW. Right now we need to be active in defining content, and once the content is defined, we need to be studying every type of web site targeted at children. Once the content has been defined, the language and the look of the content needs to be age appropriate and engaging. We cannot and presumably do not want to compete with Disney but, at least on the web, we can learn from Disney, Nickelodeon, and Cartoon Network interactive techniques and design styles which will make a required trip to a museum web site more enjoyable and less of chore. Art museums need to be much more proactive in terms of targeting programs for children on their web sites. This then is not the time to circle the wagons, but is the time to experiment and expand our reach.

The words of Elizabeth Ross Kanter, author of evolve! Succeeding in the Digital Culture of Tomorrow, will suffice for a closing admonition to art museum web professionals:

When the correct direction is hard to discern, action is better than hesitation. That doesn't mean heedlessly making sweeping changes, but rather than freezing in the headlights of oncoming change, you can at least explore, experiment, and perhaps learn what's coming down the pike...rather than waiting for differing factions to reach consensus, innovators pressed forward anyway. Leaders must establish themes, set goals, identify priorities, and assess results. They must seed new projects and weed out others ... wise leaders embrace the chance to explore forks in the road. One of them could be the next major highway.

References

Hamma 1996. Ken Hamma, Unpublished paper presented at "Virtual Museums -- Companions or Competitors", California Governor's Conference on the Arts and Technologies, Los Angeles, 1996.

Kanter 2001. Elizabeth Ross Kantor, Business 2.0 February 2001