Papers

Reports and analyses from around the world are presented at MW2005.

| Workshops |

| Sessions |

| Speakers |

| Interactions |

| Demonstrations |

| Exhibits |

| Best of the Web |

| produced by

|

| Search A&MI

|

| Join our Mailing List Privacy Policy |

Curating for Broadband

Tilly Blyth, Science Museum, United Kingdom

http://www.makingthemodernworld.org.uk/

Abstract

With the number of UK households and small businesses adopting broadband now passing the 3 million mark, museums need to consider the approaches they can use to present curator's expertise to new audiences in engaging ways for broadband. Whilst these impressive statistics represent a strong picture in the technological rollout of broadband, they do not reveal the social innovation occurring through the development of truly broadband sites. Too many Web sites claiming to be 'broadband' offer little more than video on the Web, and many fail to construct sites that socially engage users in on-line activities. The paper will argue that in order to create appealing broadband Web sites, producers need to bring together the skills and quality of television production with the active participation of the Web. In this way the creation of broadband Web sites presents new opportunities for museums to deliver public service values.

Keywords: curator, broadband, education, entertainment, public service, participation.

Introduction

In 2005 the UK presents an interesting picture in the up-take and use of broadband. Broadband use is proliferating rapidly, with the number of UK broadband connections passing the 5 million mark in September, 2004, and the UK now overtaking Germany in terms of broadband penetration. Over a third of Internet households now have a broadband connection, and according to the UK Telecoms regulator, there are around 50,000 new broadband subscribers each week (Ofcom, 2004). But whilst technological roll-out and diffusion is important, the real question surrounding broadband Internet use, and specifically its role for museums, is how broadband may change the opportunity for relationships with audiences, and whether in turn it requires new skills for curators.

What Is Broadband For?

Whilst a large amount of industry research has focused on market diffusion, very little has focused on what broadband is actually for and on best-practice examples of how it is being used. Many sites that claim to be 'broadband' sites offer little more than the need for increased bandwidth to reduce download times or archive television through the Web. UK Public Service Broadcaster Channel Four's broadband service offers subscribers the right to view on-line a very small selection of previously transmitted television programmes, whilst the BT Yahoo broadband service offers little more than a customisable homepage with streaming news channels, some movie trailers and a few music videos.

Some services, particularly for schools and universities, have taken things a little further and offer unprecedented access to archives and video based learning materials. The ARKive project (http://www.arkive.org/) from the UK-based conservation charity The Wildscreen Trust presents a unique international on-demand library of film, photographs and audio recordings of the world's most endangered species. This emotive record brings together a previously scattered collection documenting the world's wildlife.

Similarly the Education Media Online (EMOL) service (http://www.emol.ac.uk/) offers users in UK Higher and Further Education access to digitised collections of historical film. The ability to download the films at high resolutions allows film to be contextualised for use in learning resources and enables users to edit video. Thus EMOL begins to blur the line between academics as consumers of the material on the site and as media producers of their own learning material.

But broadband is capable of being more than just the provision of television or film on the Web. Broadband offers the potential to place some of the materials and techniques of television producers at the service of modes of interactivity that extend well beyond anything offered by television. Only by combining these abilities will broadband content fulfil its potential: to combine the entertaining and sophisticated experiences of television with the deep and immersive experiences of on-line community, participation and choice.

A recent report from the UK think tank Demos (Craig and Wilson, 2004) suggests that a transformation in Web use is occurring, with the actions of broadband Internet users no longer corresponding to the previously stereotypical ideas of solitary young men each sitting in front of a computer. With the onset of broadband, the asymmetry of content and users, where users passively receive and consume content, has been overturned. The report suggests that 57% of broadband users have created material to post on-line: material that they would not have contributed otherwise, and 40% are more likely to get involved in organising local events through the Internet. Broadband consumers should be viewed as active and social producers who can develop new levels of cultural involvement and, the authors claim, engagement in civic society. Unlike television watchers, broadband users are apparently not prone to 'bowling alone' (Putnam, 2002).

It is not new to argue that the use of media, and in particular the Web, is participative, not passive, and the dialogue surrounding it should be of producers, not consumers (Heppell, 1995; Livingstone and Bober, 2004), but with the rise of peer-to-peer music exchange systems and participative encyclopaedias such as Wikipedia, the era where the Internet is a tool for a nation of media producers has truly come. The growth of social networking sites shows that the creation of personal support and on-line communities is becoming increasingly important for the way we provide some forms of public service. Two examples of such a shift in the UK are the BBC supported iCan (http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/ican/), where users can gain information on campaigning and form their own local or national networks to start a campaign on an issue relevant to them, and Ultraversity, a wholly on-line degree course in action research (http://www.ultraversity.net/) for people who are normally excluded from education as they work full-time or are permanent caregivers.

Opportunities For Museums

By spring, 2004, 90% of all UK secondary schools had Internet access of 2Mbps or more, and 28% of secondary schools had 8Mbps or more (DfES, 2004). The publicly supported Regional Broadband Consortia and forthcoming National Educational Network will soon offer broadband links between home and place of learning. This rapid take-up of publicly supported broadband provision into schools and colleges, combined with consumer led diffusion into the home, offers new opportunities for museums to provide improved public service in the display and interpretation of history and culture.

Museums have long been hybrids, playing a variety of significant roles as collectors and preservers of material culture, as educators, and as entertainers. The arguments for funding have been linked to these roles and to the degree to which museums deliver value as educational institutions or places of leisure activity. The distinctive proposition for museums now is to try to build on this hybridity to develop stronger relationships with visitors and increase both real and virtual visitor numbers. This isn't just the need to bring more visitors through the door; it is also the need to deliver an encounter - with a story, an idea, an object, a person - and provide the opportunity for a broad public to invest in the cultural capital of the country. Museums need to use all the tools available - technology, information, debate - to excite, inspire and motivate the minds of their visitors and justify the expense of public funding. Broadband provides one more way to reach these audiences, but it also offers new opportunities for creating a participative dialogue with an engaging experience.

The rollout of broadband to support truly creative on-line communities looking at culture is one way that museums can continue to bridge the divide between leisure and learning. Broadband does not just offer a channel through which to tell historical stories – a channel that can bring images, animation, archive video and curator's knowledge directly into schools and the home. It can also offer museum audiences the chance to participate in active learning communities. Museums may call these broadband projects 'learning journeys' or 'entertaining experiences' – either way they have the opportunity to increase users' ability to create dialogue and engage with our common cultural heritage. Thus museum curators need to acknowledge and strengthen their skills in creating the environment for debate and discussion. Curators can't afford to perceive themselves only as academics and scholars; they also need to develop the skills of storytellers, documentary film makers and facilitators of discussion.

The Experience Of MMW

In June, 2004, the Science Museum launched a Web site Making the Modern World Online (http://www.makingthemodernworld.org.uk) aimed at students, teachers and more general audiences interested in the history of science and technology. The site was developed around the museum's permanent landmark gallery Making the Modern World.

The gallery itself draws on over 100 of the Science Museum's most remarkable objects; from Stephenson's Rocket and Babbage's Difference Engine No.1 to Crick and Watson's DNA template and the Apollo 10 command module, to display an amazing collection of 'firsts' representing the most important steps in science and invention. As visitors move through the gallery, a timeline takes them through a chronological journey which employs the richness of the museum's collections. In parallel to this 'iconic' museum display, the objects are contextualised. Nine historical themes run on one side, reflecting our changing attitudes to science, technology and medicine. These range from Enlightenment and Measurement, via The Industrial Town in the mid nineteenth century, to Defiant Modernism a century later, and the sequence ends with The Age of Ambivalence which explores our current tentative relationship with science and its products. On the other side, five displays illustrate the impact of technology on our everyday life to show how scientific and technological knowledge has been used in work, play, for health and forms of social control.

Figure 1. Making the Modern World gallery at the Science Museum

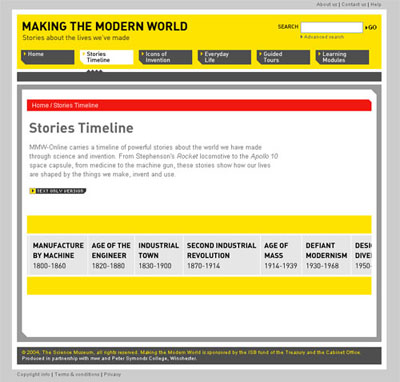

Making the Modern World Online (MMW) uses the same contextualising themes of the gallery to structure content in the site. An interactive timeline allows the user to access over twenty curatorial stories and nine historical themes from the eighteenth century to today to explain the development and the global spread of the modern industrial society.

Figure 2. Homepage of Making the Modern World on−line.(http://www.makingthemodernworld.org.uk)

The site was funded by the British Treasury and Cabinet Office's 'Invest to Save' (ISB) initiative which aims to create sustainable improvements in the capacity to deliver public services. ISB initiatives bring together two or more public service bodies in an innovative way to improve services or to reduce costs. Through Making the Modern World it brought us (the Science Museum) together with a specialist school (Peter Symonds College, Winchester) to show how on-line learning materials could be created to increase access to and interest in science and history education. As well as aiming to increase participation in the cultural and heritage sectors, the project tested whether two institutions reliant on public funding from different government departments (Education; Culture) could work together in a specific area to create improvements in service delivery.

From the outset the Web site was created to increase the understanding of history and artefacts through contextualisation using a range of multimedia techniques. Curators were asked to extrapolate from the iconic objects displayed in the gallery to develop rich and detailed stories for the 'Stories Timeline' part of the site. These stories were placed in an interactive timeline corresponding to the same themes as those used in the gallery.

Figure 3. Stories Timeline on Making the Modern World. (http://www.makingthemodernworld.org.uk/stories/)

Although the main part of the rich media was developed for the 'Stories' section of the site, four other areas were developed: Icons of Invention, Technology of Everyday Life, Guided Tours and Learning Modules. The 'Icons' section represents 116 most prized treasures in the Science Museum's collections, from 1750 to the current day. The 'Everyday Life' section looks at how the objects of invention and methods of technological production are woven into our daily lives at home, at work or at play. With over 400 objects, the site represents a serious look at how science and technology connect to ordinary people. The 'Guided Tours' draw connections across time to bring together the people, scenes, icons and objects relevant to particular themes. These were particularly focused on engaging the socially excluded. For instance, one looks at the part played by women in science and technology, whilst another demonstrates the role of specific technologies as tools for the employment and integration of successive immigrant communities. The 'Learning Modules' were developed by teachers at Peter Symonds College. The curators and teachers worked together to identify areas where the gallery content overlaps with the learning objectives of the 16+ 'A' and 'AS' level curricula for history and the sciences.

In the creation of the content, curators were asked not to think about the production of text, but to focus their knowledge on the most compelling stories that would allow them to bring in the images, video, trade literature and archives that were available on the topics they were developing. In this way they used their understanding of the museum's picture and library collections – not just artefacts – and translated them into an explorative learning journey about the object, its invention, its social and cultural significance, and how it worked.

Each story was developed in modular form comprised of a number of 'scenes'. The team developed a variety of distinct scene types defined by their mode of interaction with the user and the assets involved:

- text and image,

- interactive maps,

- technical deconstructions,

- montage,

- mini-documentary,

- dramatic reconstruction.

The techniques used in this variety of scene formats brought together information, navigation and narrative devices to represent the historical world. Whilst some techniques, such as the animation or layering of a map or the graphical breakdown of how a technical device works, are not unique to this site, others were intended to be much more innovative. In the case of dramatic reconstructions, curators selected extracts from archive letters or speeches and worked with the production team to develop scripts recorded by actors. These 'audio dramas' were illustrated using original images from the archives and multimedia devices to bring history alive. The development of a small number of richly featured 'Mini-documentaries', offering the users either a television style linear narrative or a branching exploratory structure, allows the audience to choose how (and how deeply) to explore events and issues as varied as the development of the German V2 Rocket Weapon, the impact of the Cold War on the space race, the Rainhill trials to examine how to power the first locomotives, the development of personal computing, and the rise of environmentalism from Rachel Carson to Greenpeace.

By considering the assets and the storytelling devices available to them, curators developed compelling content with a modular structure. They worked closely with a team from the interactive design agency SAS (http://www.sasdesign.co.uk/) to identify the best approach with the narrative and assets available. SAS brought knowledge of the latest technical competencies and high production values to the content, to ensure that the presentation of curators' knowledge was impressive and innovative.

In this way curators and interactive developers created the content that allows users each to undertake a personal 'learning journey' – an individual but contextual story about an object, a period or area of technology, one created through individual navigation of the site. For instance, if you first come to the site to investigate James Watt, you will find many more perspectives than just a biography about the 'great engineer'. You get a complete story of his life and inventions, including an audiovisual reconstruction of his 'eureka moment' when he thought through the mechanism for creating a separate condenser. This is recreated using an actor reading Watt's own words together with images from our archive. The user can also find a complete animated reconstruction of the Watt engine and explore how it worked as well as what its impact on society was. The user can then transfer this knowledge to the museum artefact, to look at the object within the museum culture.

Evaluation conducted during the development and after the launch of the site has shown that users enjoy being able to choose to go deeper into a subject if they find it interesting. Also, the use of images, video and audio to break up the text into manageable chunks encourages them to read on. By combining archive, speech, image sequences and editing techniques with dynamic multimedia, the site offers an audience experience far beyond that possible in the static exhibition. Most of all, users loved the 'rich media' parts of the site. They perceived these to be modern, interesting and fun, whilst being "a really good way of packaging information." About one-quarter of users specifically mentioned liking the videos and rich media and would generally spend more time watching these compared to reading text. Users' session times increase dramatically when they come across the rich media parts of the site, and often users exclaimed that they would like to see far more of the site approached in this way.

Making the Modern World Online creates a dynamic and deep environment by using many of the storytelling techniques of television and film to create an engaging user experience. Although the site did not develop any community tools or contain any participatory elements, its construction did enable the Science Museum to go some of the way in identifying what a good broadband site is, what it isn't, and what it could be.

What Broadband Is (And Isn't)

A truly broadband site is certainly not the Internet with video, even though ISP's and broadcasters seem currently to think so. Certainly very few sites move beyond this. What we need to do is to learn from television rather than re-playing it. MMW has shown us that broadband museum content will be far more meaningful and accessible to the audience if we can apply some of the tools and techniques of television and documentary film-making to tell stories. A broadband historical and cultural site of this type can be thought of as a 'deconstructed documentary', where instead of being told a single linear narrative, users are encouraged to take their own non-linear paths to understand how an expert may have reached the conclusion presented. Issues where debate resides emerge more naturally.

Broadband sites such as the National Theatre's Stagework (http://www.stagework.org.uk/) provide an interesting step in the right direction. Audiences are invited to go behind the scenes and rehearsals to understand the complex process of making theatre performances for the general theatre-goer, the life-long learner and curricular audiences. Yet even innovative sites like this that offer rich media as a way of deconstructing a production don't offer the chance for on-line contribution or participation. The learning model is moving closer to one of communication rather than dissemination, yet the on-line tools for participation are still not included.

But perhaps this is the way forward for broadband museum content: to go beyond the television 'broadcast model' and use these interactive stories to develop participative communities with our audiences.

Future broadband sites should consider how communities have effectively been developed in narrowband sites, and how to apply some of these techniques to sites with the high production values of rich media. For many narrowband sites this has been through the creation of symmetry, where individuals can submit ideas and in some cases media to stimulate discussion. This simple approach to discourse and dialogue could be combined with broadband rich-media entertainment to present a very powerful way of engaging new audiences and connecting them to our national cultures.

Imagine a part of Making the Modern World Online where audiences can contribute their own story about the day a V2 bomb dropped on their family house in London, or the contribution of real stories by people who travelled to Britain in the 1960s from the Caribbean to work as part of the London Transport workforce. This type of rich narrative – whether video, images or text - would add a level of depth and interest that isn't possible without contributions from a broad audience. Alternatively, users could develop their own 'Guided Tours', stitching together scenes, media and images from the site using their own narrative links, or creating new meanings and content from the published assets.

Developing broadband sites in this way would also necessarily involve museums re-stating some core-values – to make collections accessible through a variety of approaches and bring (real and virtual) visitors into contact with some of the most important stories and icons of technology in our culture. I am not advocating that broadband sites become a way of developing yet more edutainment through the use of televisual techniques, but that they present one way of reaffirming that museums are cultural centres of expertise which – in the Science Museum's case - act to stimulate understanding and engagement in innovation, science and society.

Where Does That Leave Museum Skills?

To argue that curators should view themselves as storytellers and teachers as well as scholars is not to suggest that the traditional skills of museums are out-moded. Far from it. Curators have always had to develop strong skills in interpretation to a variety of audiences, and museums' collections have always been viewed as resources to be used by students, scholars and amateurs alike. But curators will now need to form new collaborative teams where their skills as story makers and documentary Web creators can be enhanced by interactive producers and community facilitators. Curators need to think structurally and visually about the form of their narrative whilst maintaining a focus on the variety of stories surrounding a museum artefact. They must be prepared to open up debate and offer their tools for discussion to others, so that they not only act as authoritative voices but also act to stimulate understanding and engagement in the context of the 'real' object. It is their role to inspire informal learning by encouraging interest in and knowledge of arts, science, technology and history through accessible content.

Public Service Through Broadband

This paper has argued that broadband presents new opportunities for museums to deliver high quality content with impressive interactive production values directly into schools and the home. In order to be successful, this must not just be the development of rich media content that uses many of the techniques of television, but the creation of broadband channels for discussion of, and participation in, history and culture. In this way museums can play important roles in creating active learning communities and delivering public value to all sections of society.

Rich media content should provide new experiences and enjoyment for users, and also draw audiences to a site, but the presentation of information and the Web site experience should move beyond linear documentary to the creation of tools for community debate and conversation. Increasingly, users expect to create and post on-line content. This desire for communication and discussion should be harnessed to increase knowledge and participation in cultural content.

For a country like Britain, where Public Service Broadcasters occupy a central place in cultural life, the erosion of audience figures for previously dominant terrestrial television channels causes some alarm. As digital TV channels proliferate and the viewing shares of each channel nosedive dramatically, digital platforms such as broadband Internet are one way of filling the public service gap. Museums and other cultural institutions should seize the opportunity to prove their public value and ability to fulfil their public service remit. Content developed for a broadband service today may well have a larger audience and more impact than that developed for a digital television channel tomorrow. In the future we can make no assumptions about the 'primary' channels to audiences. Only recently the UK regulator Ofcom proposed a new type of institution, a Public Service Publisher, that might commission broadband content from cultural institutions and other social groups to ensure that public service values evolve in the broadband age. This PSP may never be created, but the suggestion shows that at the regulatory and policy level there is acknowledgement of the role museums could play.

Broadband presents museums with the chance to show that we can be a nation of producers of cultural content, not just consumers, and that museums have important roles to play in exciting, inspiring and motivating a variety of audiences to get informed and involved. Museums must make sure they are channels through which cultural assets are used, distributed and re-produced, so that they disseminate, inform and reflect our diverse cultural heritage.

References

Craig, J. and J. Wilson, 2004. Broadband Britain: the end of asymmetry? Demos Report. Consulted 28 January 2005. http://www.demos.co.uk/BroadbandBritain_pdf_media_public.aspx

DfES, 2004. ICT in Schools Survey 2004. ICT in Schools Research and Evaluation Series: Number 22. Consulted 28 January 2005. http://www.dfes.gov.uk/research/data/uploadfiles/ICT_in_Schools_Survey_2004.pdf

Heppell, S, 1995. Wait a minute, didn't we already know something about learning? Keynote presentation to the Australian Computers in Education Conference. Consulted 28 January 2005. http://www.educationau.edu.au/archives/CP/REFS/heppell.htm

Livingstone, S. and M. Bober, 2004. Active Participation or Just More Information? Young People's Take up of Opportunities to Act and Interact on the Internet Research report from UK Children Go Online project. Consulted 28 January 2005. http://personal.lse.ac.uk/bober/UKCGOparticipation.pdf

Ofcom, 2004. The Communications Market, 2004. Consulted 28 January 2005. http://www.ofcom.org.uk/research/industry_market_research/m_i_index/cm/cmpdf/?a=87101

Putnam, R., 2001. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon & Schuster.

Cite as:

Blyth, T., Curating for Broadband, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2005: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 31, 2005 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2005/papers/blyth/blyth.html

April 2005

analytic scripts updated:

October 2010

Telephone: +1 416 691 2516 | Fax: +1 416 352 6025 | E-mail: