Papers

Reports and analyses from around the world are presented at MW2005.

| Workshops |

| Sessions |

| Speakers |

| Interactions |

| Demonstrations |

| Exhibits |

| Best of the Web |

| produced by

|

| Search A&MI

|

| Join our Mailing List Privacy Policy |

Leveling the Playing Field: Empowering Learners with Primary Sources

Cynthia R. Copeland, The New-York Historical Society, Ray Shah, Gavin Lee Foster, David Ellis and Petar Bojkov, Think Design, Inc., USA

Abstract

American History is often undervalued, disliked and ignored by both students and teachers in today's schools. This paper looks at the incarnation of an on-line object-based educational (K-12) Web site which helps enliven teaching and learning history. With content steeped in the topic of the American Revolutionary War era, the site intends to provide the experience of direct engagement with rich and diverse historical resources to educators and learners. This occurs in multiple ways throughout the site; however, it is the site's main feature – the on-line exhibition tool – that embraces object-based learning methodologies to promote the development of skill sets in information literacy, evaluation and higher-ordered critical thinking for educators and learners alike. As users learn how to curate their own exhibitions, they also begin to understand and practise the historical processes of weighing evidence and developing methods of inquiry, thereby learning to think like historians.

Active participation in learning through the incorporation of primary material in classroom instruction greatly improves student interest, ability to retain knowledge, and overall satisfaction with the learning and teaching process. The integration of primary sources and new media technologies is reshaping the way education is practised. And access to primary sources, once the sole domain of curators and scholars, in an on-line format levels the playing field and opens the possibilities for greater meaning to the legacy that is history– at any age

Keywords: primary sources, object-based learning, history, inquiry-based learning, educational site (K-12), on-line curatorial tool, interactivity

Rationale

The demands placed upon history and humanities educators at the primary and secondary levels have never been higher. Teachers are expected to prepare their students not only to perform well on assessments and meet higher learning goals in order to satisfy state and national mandates, but also to produce good citizens.

Teachers frequently are pressured into surveying vast periods of time and complex events– such as the American Revolution or the Civil War– swiftly and efficiently, but with little depth. In short, American history is often taught by rushed, ill-prepared and unsatisfied teachers, and disliked or ignored by their students. Such findings can be found in the U.S. Department of Education's National Center for Education Statistics report (2001), which painfully points out that America is producing a vast majority of young people who are historically illiterate. And an earlier study conducted in 1991 by the same agency noted that more than half of all social studies teachers did not major or minor in history. Furthermore, Gorn (n.d.) argues that the lack of training puts enormous pressure on teachers to teach historical processes of researching, analyzing and interpreting primary sources, to meet the requirements of standards and student preparation for standardized tests, when they themselves are anemic in these skill sets.

Long considered a virtue of American citizenship, a solid understanding of history– of one's community, state and nation– is ever more critical in evaluating current events in today's information-saturated society. Yet according to recent well-established research, many students, particularly in middle and high schools, are disengaged from the fundamental institutions of government and basic processes of American civic life. Students too often describe history as 'boring and irrelevant.' Students also frequently feel that teaching methods are dull and abstract. According to Loewen (1995), the common reliance on massive textbooks which attempt to summarize and 'explain' all there is to know about any given subject strikes many students as remote and uninspiring.

The New-York Historical Society's (N-YHS) educational philosophy supports the findings in national research and various sources indicating the importance of integrating primary source teaching methods into the classroom. The Society advocates that students learn history best through direct discovery and use of primary sources. We have a long and successful tradition of leading students on discovery tours of our collections, through temporary and permanent exhibitions, The Henry Luce III Center for the Study of American Culture, hands-on workshops with items from our Touch Collection, and other on-site programs. We also partner with local schools to improve the teaching of history in the classroom.

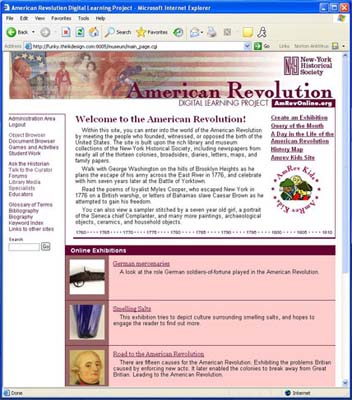

Since the early 19th-century, The New-York Historical Society has been collecting a vast array of artifacts and documents pertaining to the American Revolution and Colonial era. As we ushered in the 21st-century, the Historical Society chose to remain relevant by providing to millions of learners, of all ages, access to these and many other collections that shape the story of American culture. Greater access to primary sources is the basis of the New-York Historical Society's creation, the American Revolution Digital Learning Project (ARDLP), (http://www.amrevonline.org).

Taking advantage of changes in educational practices and the incredible recent leaps in information storage, retrieval and manipulation, the Historical Society, with generous funds from the Department of Education (Funds for the Improvement in Education), and CitiGroup Foundation, is preparing to launch the American Revolution Digital Learning and New Media Project. Three years in the making, at its heart this educational resource is a digitized compilation of upwards of ten-thousand theme-related primary materials, accessed via the Web and supported by on-line educational materials and training seminars.

AmRevOnline.org– Genesis

The Society's ARDLP is under construction as a historical source repository for educators and students on the Internet. Now, you can not only browse authentic and topical primary source materials, but also interact with them. Presenting resources in an on-line format is naturally beneficial to all learners, as Web sites (and other new media technologies) tend to address learners' various modes of cognitive reception. In other words, in the world of multiple intelligences, the four most widely recognized categories of learning styles include those who are visual (learn through seeing), auditory (learn through listening), tactile (learn through touching) or kinesthetic (learn through moving, doing).

In anticipation of taking our maiden voyage, the N-YHS team enthusiastically went straight to the source to assess the needs of teachers. Summative data collected from a National Teachers' Summer Institute sponsored by N-YHS in 2001 indicated that our Web site development should include a large collection of objects and documents that students could access and analyze closely. One teacher from Texas said, "The West needs your treasures." Many teachers stressed that we should also provide lessons and activities based on the material. Transcripts of the documents and information about the objects should also be provided. One teacher, though, cautioned that the Web site should not focus only on New York, because teachers from other states might browse right past it. During the Institute, teachers enjoyed hands-on experiences with selected objects from our collection. They particularly loved the object-study sessions, where they handled, examined, and made inferences between seemingly unrelated objects. Several of them wondered if we could have 3-D views of the objects on the Web site, so that students could 'handle' them as the teachers did on-site. Almost all of the teachers said that they would need a place to exchange lessons and ideas with their colleagues.

Fig. 1: Current Prototype of the AmRevOnline.org Web Site

The site has undergone three iterations. In the first, there were usability issues. The second, based on the exhibition, Independence and its Enemies, served as a prototype. It was created and refined based on feedback from usability tests. This exhibition was a wonderful place for us to begin as it demonstrated the breadth and depth of both the library and the museum collections. That site contained approximately 130 images, to which we added lesson plans, special features such as a lens magnifier, a game, and later, as we began selecting additional items from the museum collection, an item browser. The prototype is now being transformed into the third and final iteration.

Site Features

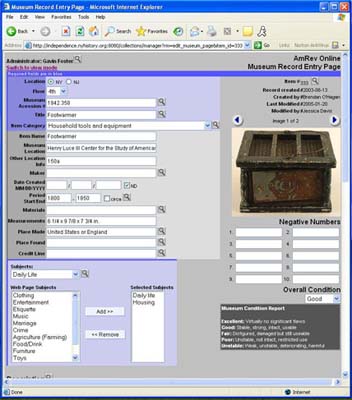

Collections Manager

It was realized during the design process for the ARDLP Web site that existing collection management systems in use by the N-YHS neither had the flexibility nor encompassed the fields required by the ARDLP team. Having identified the need for a more specific tool for cataloguing American Revolution-related objects and documents for use with the Web site, the Collections Manager tool was developed.

Fig. 2: Object Record in the Collections Manager

The Collections Manager tool has a Web-based interface that allows data related to objects and documents in the N-YHS collection to be catalogued. It allows Museum data to be imported (currently we use MIMSY & TMS), but also allows new independent records to be created. The Collections Manager also allows digital images of objects and documents to be viewed and associated with those items.

Future plans for the Collection Manager tool include adding the ability to crosswalk existing data to the Dublin Core Metadata Elements, and allow this data to be exported or accessed via an on-line search API.

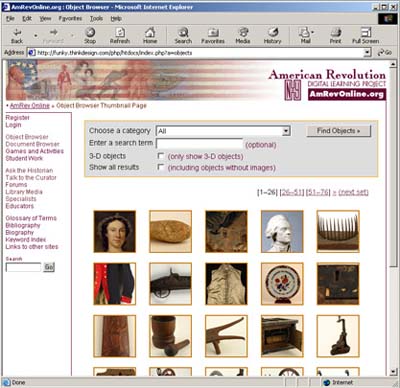

Object & Document Browsers††

The core of the ARDLP Web site is its Object and Document Browsers. Items from the N-YHS collection are seen as belonging to two broad categories, objects and documents. Through the Object and Document Browsers, visitors to the site can access over 8,000 American Revolution-related objects and documents from the N-YHS collection. High-quality digital images of the item are available to be viewed, in conjunction with the cataloguing information and additional research for each object, which has been added to its record via the Collections Manager.

Fig 3: Object Browser Main Thumbnail View

http://funky.thinkdesign.com/php/htdocs/index.php?a=objects&page=1

Some objects also have 3-D views available, allowing the object to be seen and rotated in a 360-degree plane.

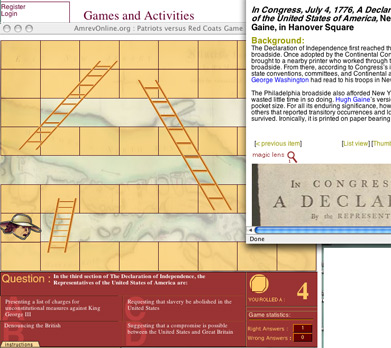

The Magic Lens tool has proved particularly popular on the site. The Magic Lens allows a magnifying glass effect to be achieved over a digital image, so that an area of the image, which moves with the mouse, is displayed in an enlarged version. For some handwritten documents, the Magic Lens is used to provide access to a transcript of the document.

Fig. 4: Document Browser Magic Lens Transcript http://funky.thinkdesign.com/museum/items.cgi?rm=magic_lens&photo_no=1&item_id=4071

All these aspects of the Object and Document Browsers help the visitor to feel much closer to, and achieve more interaction with, the objects and documents in the collection, than would be possible even in the museum itself.

Object-Based Learning Application: Traditional Approach

Integrating this element of the site into classroom instruction enables students to look directly at objects and documents and draw conclusions based on constructed questions and responses. Teachers may choose a content-based approach, opting to lead instruction that produces knowledge-based, factual results. Such outcomes are demonstrated by developing very specific questions and activities that satisfy content-based goals of purposeful learning.

Fig. 5: The page guiding student observations of 'Andrew

Skinner and George Taylor,

Map of New York City, 1781' http://test.amrevonline.org/museum/educators.cgi?rm=show_lesson&name=_doc5Activity

A constructivist and student-centered outcome can also be realized by allowing students to explore the document on their own and develop their own lines of questioning strategies. This type of approach is a great motivator for learning, generating more thoughtful responses, and interesting student work.

Exhibition Tool

The implementation of the item browsers opened the way for the development of the Exhibition Tool. The Exhibition Tool allows students to visit the site and create and curate their own virtual exhibitions, containing objects and documents that they select from the item browsers.

Fig. 6: Vanguard High School: Events that Caused the American

Revolution.

Opening page [Student Work]

Students may create exhibitions containing different sections. Within these sections objects may be added and given individual labels, and optionally grouped with a group label and heading.

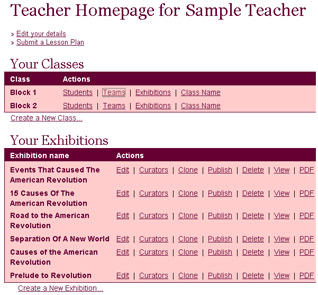

Fig. 7: Teacher Homepage from which students may be added

or

teamed up with one another; exhibitions viewed & edited before

submission for publication

Teachers can register students in classes and sub-groups within these classes and assign particular exhibition topics to the groups, or just to individual students.

Fig. 8: French & Indian War section of 'Separation

Of A New World'.

This team linked the judicial reforms that followed

Salem's Witch Trials to the revolution.

The Exhibition Tool thus enables students to enhance their critical understanding of the American Revolution through direct, albeit digital, interaction with primary sources in a way no textbook or museum visit could feasibly provide. Students can use the Exhibition Tool and learn to 'think like historians' by using primary sources from the N-YHS both with or without guidance from their teachers.

Fig. 9: Student exhibition using thumbnail images to lead into exhibition topics

The Exhibition Tool and Object and Document Browsers both enliven the classroom and provide students with opportunities to sharpen their analytical skills while building their memories of key events and personalities from the American past.

Students and teachers may ask to have their work published on the site. The exhibition must have the approval of the N-YHS advisory board, composed of teachers, historians, N-YHS staff and others. If criteria are met, the site is then uploaded for all to see, and will become a part of the permanent archive.

Object-Based Learning: Critical and Creative Thinking Approach

The Exhibition tool is meant to encourage and motivate students' understanding of the objects and documents in proper context. Of course teachers can apply any method of instruction necessary to achieve final assessment of student skill, knowledge and understanding. However, this tool, when tested among high school students, proved to be an incredible tool for learning, and raised levels of critical thinking.

The Exhibition Tool when presented for exploration or discovery of information on the subject allowed the construction of new knowledge and forms, and was conducive to model building. When students received instruction to fulfill certain requirements, they worked diligently and with great enthusiasm. Many of the students were so immersed in their research they stated that they were on-line during the wee hours of the morning looking for images to illustrate their interpretations of this defining event from the past. They also indicated how frustrated they were when the site was inaccessible because of work being done by the developers during the early morning hours.

A Case Study – Vanguard High School, New York City

Vanguard offers small classes with intense interaction between students and teachers, creative lessons, and a real sense of community. Many of the students have not had great success in their primary education, requiring a great deal of remedial work. It is one of a handful of alternative high schools across the city that require students to complete a set of nine graduation portfolios in addition to passing five Regents examinations. Vanguard has no electives.

The school has grades 9-12, and class size is about 20 students per teacher. The 9th grade peaks with 140 students, while the12th grade student body ebbs to approximately 40 students, suggesting a high drop-out rate. Students receive individualized attention in efforts to identify and to resolve problems as early as possible. Parents are active in their children's education, attending meetings with their child and the child's advisor. The graduate rate is about 50%; attendance is noted at 81%, and there is a seven-year graduation rate of 74.5%.

Creative instruction drives project-driven classes that are demanding. Though teachers struggle to meet the needs of all learners, some students find the work too difficult. Investigation and inquiry-based methods are taught to help students acquire better in-depth research and critical thinking skills to explore topics of study. Knowledge and understanding are demonstrated through portfolio assessment and oral presentations. Students are taught to discuss their ideas, identify evidence, and ask critical questions (Jacobs, 2003).

In the fall 2004, the ARDLP spent three weeks working with a grade 12 humanities teacher and his students, piloting the Exhibition Tool. The students had a choice, either to curate an on-line exhibition, or to create a reading book. Approximately 15 students selected the Web site project. The students were prepped on events leading up to the American Revolution and the impact of the War on the colonies. Their assignment was to locate objects and documents in a 'free- style' to illustrate fifteen causes of the American Revolution and the War, including Non-Importation, the Boston Tea Party, Coercive Acts, the Townshend Acts, and more. The students were instructed to write supportive text and captions for an on-line exhibition. The students could work independently, or they could collaborate with a partner. They had nearly ten days to complete their projects.

ARDLP Observations

At first, the students appeared to be caught up in the novelty of the site. There were so many features and so many objects and documents that it was difficult to remain focused and on task. It was later determined by both teacher and students that rummaging around the site was just part of the process of discovery and exploration. Once that was out of their systems, most students tended to be literal in their approach to looking for objects and documents. By consensus, the students were dependent on the keyword search and showed great frustration and disappointment when items for topics did not show up in great numbers or at all, in response to their searches. For example, when they typed in "non-importation," most of the students expected to see a stream of images that screamed out "THIS IS ABOUT NON-IMPORTATION!"

With some coaching the students finally realized that they needed to expand on their prior knowledge of the subject matter. They studied the background prior to engaging in the activities and were being challenged to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of the content. Once the goals were clearly defined, the layers of learning unfurled, and the students became absorbed in object-based learning– learning from objects and primary sources through exploration and context. They grappled with the complexities of learning and understanding to find the interconnection between the primary sources and the ideas that the sources communicated.

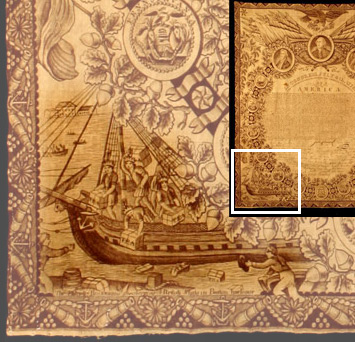

In the end, the students made oral presentations of their work. The work ranged from adequate to excellent. One student with time management issues, and who met all sorts of challenges throughout his daily life, managed to produce a small exhibition in two days. The content was all jumbled up in his head, but some of his observation skills were highly acute. For example, when trying to illustrate the event known as the Boston Tea Party, he found the perfect image, yet it wasn't obvious to other learners. He identified a textile, and on the lower left corner of an elaborate kerchief, which focuses attention on an image of George Washington, was this amazingly rich engraving of that well-known historical event. This detection may not seem monumental to some, but for a learner attempting to generate his or her own meaning based on investigation, that discovery demonstrated his ability to observe, inquire, analyze and reflect, therefore using skill sets practiced by professionally trained historians.

Fig. 10: Detail of kerchief depicting Boston Tea Party http://funky.thinkdesign.com/php/htdocs/index.php?a=object&item_id=2753&cat=49&page=2

Student Outcomes

After the presentations, we collected summative data from the students. Their surveys comprised open-ended questions as well as questions ranked on a rating scale of 1 – 5, one being a not all type response and five, extremely so. We inquired about levels of appropriateness for grade level; comprehensiveness of the site's content; time spent on the Web site; opportunities to interact with others; enjoyment of use; instructions for using the site; interest in doing more social studies learning on-line; what they liked and didn't like about the site; and suggestions for improvement. Twelve out of the fifteen students returned the surveys, with a range of answers. Scores for navigability were all over the map, with one – 1, and several 3-5s. Most students found the site to be extremely comprehensive. Twelve out of the twelve returned surveys indicated they would like to do more social studies-based learning projects on-line. Other comments included:

On likes and dislikes:

"I loved reading documents, and making connections to artifacts. I didnít like the editing process."

"I like how background information was provided with every picture or document."

"The clarity of the magic lens."

"I like[d] the fact that we can add pictures to our test. What I least like was that some pictures that we needed were hard to find."

"I like the fact that it is easy to navigate, but I didnít like the fact that itís kinda hard to find picture for topics."

"What I like[d] was how it (assignment) was on a Web site and how we helped [those] people with some feedback"

On what they thought was the main goal of the site:

"To help teach kids how to learn online and not just in a textbook."

"To familiarize students with the artifacts found at the museum and the history surrounding them."

"To help students comprehend the American Revolution in a fun and interesting way."

"The main goal of this web site is to give us a better understanding of the American Revolution."

"It's kind of like an online museum, so rather than have to go out you can sit on a chair and get the same experience."

And, on suggestions for improving the site:

"I think helping to categorize the images a little better so it would be easier to find them."

"The site could be improved by adding more pictures and objects."

"Having more object[s] and document[s] to make you understand more."

"Really nothing."

"Finish the Web site."

"I suggest improving the editing process, when writing text and having well informed teachers, teach the students how to navigate and benefit from using the web site."

"Really nothing, it might be hard to find objects but at least you have to do some work."

Teacher Outcomes

Initially, the teacher was a bit disappointed with the student work. The teacher had hoped to give these students, whom he felt had a disadvantaged education, a great experience in learning. Instead, he felt frustrated that they were not able to make the giant leaps of inquiry- and object-based learning independently. When he observed the majority of the students struggling to apply their intellectual skills to their knowledge and understanding, he felt a bit defeated. He also determined very early on that the Web site was probably more of a 'diversion rather than a teaching tool.'

However, after re-examination, given the short time frame for unit study, the teacher realized that he had tried to cram in too much material. He also recognized that a 20-30 per cent reduction in the research assignment (examining 3-5 causes) would have yielded a manageable assignment, leading to concentrated research, greater knowledge and understanding, and a better experience for the students. It is likely that the revelation suggested that a well-developed plan and improved implementation, plus, a greater familiarity with the tools at hand, would have produced the results he was really trying to achieve. He realized that the site can be used to center focused learning, or it can be used for broad exploration, as occurred at the outset. And after he saw the presentations and looked closely at the on-line exhibitions, he came to realize that real learning did indeed occur in that classroom. This also became evident from the information gleaned from the student surveys.

Other Interactive Aspects of the Site

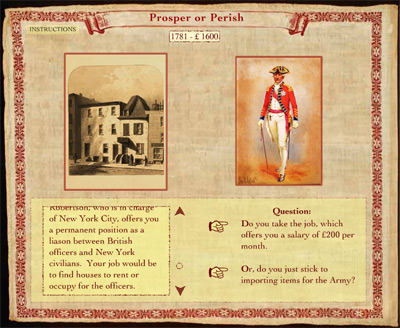

The ARDLP Web site has integrated other methods of reading primary sources. We have created several games. Some games have been created by students, others by teachers and by other people who know how to have fun with primary sources. Prosper or Perish: the Frederick Lindsay Loyalist Game is a role-playing game where students empathize with the character and gain understanding of what it meant to live in the past, and that choices always have consequences. The underlying lesson of this game is that learners, in this case gamers, generate their own meaning based on investigation and exploration.

Fig. 11: Patriots Versus Redcoats Game http://test.amrevonline.org/museum/games_and_activities.cgi

Another challenging game is actually a content-based lesson in disguise. In the Patriots versus Red Coats Game, the essential outcome is for students to acquire knowledge (facts) about the impact of the Revolution on New York City. Critical data is explored and meant to reinforce what is ( or should be) currently known by students. This is a question and answer game where a player chooses a side (Rebel/British) and answers questions related to the on-line exhibition. Students can play this game individually or in groups in the classroom. It can serve as a jumping off point into bigger ideas about the social, political and personal ideals of the era. But more importantly, working with primary sources on the Web brings students to a new understanding of what it means to dig and look deeply beyond the obvious.

Fig. 12: Prosper or Perish Game http://test.amrevonline.org/museum/games_and_activities.cgi

Making collections available on-line offers great flexibility and endless possibilities for educating the public in general, and educators and students specifically. In order to start the educational process, access to information must occur. Information access empowers audiences in unimaginable ways: to conduct research, make discoveries, draw connections, engage in higher ordered thinking, and add to the interpretation of the content in the collections. Primary source learning on the Web helps us to observe more carefully, formulate questions, conduct research, discuss, collaborate, analyze, derive new meaning and draw conclusions. This type of educational tool encourages active engagement from audiences and lessens their roles as passive receivers of information (Rhyne, 1997).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to recognize Brendan O'Hagen, Jessica Davis, Gary Wong, Maureen McGillan, Kathleen Hulser, John Hitz, Phyllis Trager, Nicholas Crawford, Mary Pattee, Elizabeth Ketcham, Kathryn Actis-Grande, the museum, print room, library, education, rights and reproductions staff at N-YHS, Kristin Derimanova, Todor Radev, Jon Berry, the students and faculty at Vanguard High School and numerous others who have greatly contributed to the creation of this Web site and to this paper.

References

Gorn, Cathy (n.d.). Getting Students to Like History is Not

Impossible. Teachers Lounge Archive. n.d.

consulted 26 January 2005. Center for History and New Media, George Mason University.

http://hnn.us/articles/777.html

Jacobs, Kevin (2003). Inside Schools.org. The Independent Guide to New York City Schools. http://www.insideschools.org/fs/school_profile.php?id=980

Loewen, James W.(1995). Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. New York: The New York Press, 1-7.

Rhyne, Charles S. (1997). Rethinking Research. Introduction to the session on The Immense Potential of Museum Web Sites for Research. Museums and the Web, An International Conference; 1997 March 16-19; Los Angeles, California., consulted 25 January 2005. http://www.reed.edu/~crhyne/papers/rethinking.html

U. S. History National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). (2001). U.S. History Highlights, The Nation's Report Card.

Cite as:

Copeland, C. , et al., Leveling the Playing Field: Empowering Learners with Primary Sources, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2005: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 31, 2005 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2005/papers/copeland/copeland.html

April 2005

analytic scripts updated:

October 2010

Telephone: +1 416 691 2516 | Fax: +1 416 352 6025 | E-mail: