Papers

Reports and analyses from around the world are presented at MW2005.

| Workshops |

| Sessions |

| Speakers |

| Interactions |

| Demonstrations |

| Exhibits |

| Best of the Web |

| produced by

|

| Search A&MI

|

| Join our Mailing List Privacy Policy |

MuViPlan: Interactive Authoring Environment To Plan Individual Museum Visits

Stefan Göbel, and Axel Feix, Digital Storytelling Department, ZGDV Darmstadt e.V., Germany

Abstract

Museums are among the most interesting places to encounter cultural heritage, and learn about history or physical and biological phenomena. Hence, many people describe the museum as 'the 3rd learning place' in addition to the parental home and the school or university.

Museums can provide a great variety of original data and exhibits enhanced by digital media. The trend to interactive installations has led to guided tours with tour guides or with mobile companions: audio-based, PDA, or smartphones. Young visitors, especially, compare museums with science centers or theme parks and expect highly interactive artifacts providing a game-based physical setup or tour to explore history or any phenomena.

However, there are still several technical and practical obstacles to the development of such applications. On the one hand, museum staff needs to create content with 'adequate' representation enhanced by digital media, 'appropriate' interaction metaphors, 'exciting' physical setups, and 'appropriate' learning concepts – all to match the interests and background of (a lot of) different visitor groups. On the other hand, visitors have to be 'high-tech friendly', able to combine the real with the virtual and willing to spend some time to plan their individual museum visits.

Based on a state-of-the art analysis of existing authoring tools, this paper introduces MuViPlan as an interactive authoring environment addressing those issues and enabling a (more or less 'virtual') collaboration between museum staff and visitors. MuViPlan products build the basis of various museum applications ranging from terminal applications to Web sites, mixed reality installations or mobile applications such as tours or guided tours. Both museum staff and visitors (individuals or groups: families, school classes) can use MuViPlan in order to prepare, process or evaluate a museum visit.

Keywords: Authoring tool, Storytelling, individual museum visit, museum applications, tours

Introduction

Recently, there has been a noticeable trend to transform museums from fusty and antiquated repositories to stimulating cultural locales. For example, museums have been enhanced with new media and services such as Web sites, information and material for visitors and teachers, virtual galleries, guided tours, etc. As with theme parks or adventure worlds, the 'cathedrals of the 21st century' (Opaschowski, 2000), a lot of people like to spend their leisure time in museums to enjoy culture.

Various museum communities, such as national and international museum associations (e.g., Mai-Tagung in Germany), research programmes and networks (e.g., FP6, DigiCult projects of the European Commission, IST programme such as 'MINERVA') and conferences (e.g., Museums and the Web, ICHIM or EVA) support this trend and encourage new methods and concepts from the perspectives ofscientists in a museum, museum curators, exhibition managers, museum pedagogues, Web site administrators, marketing directors, IT/service providers, teachers, individual visitors, and groups (pupils, kids, elderly people, families..).

From the technical point of view (apart from basic infrastructure with databases for document archives, a network, terminals and software for archiving, searching, etc.), interactive installations, story-driven tours and VR/AR applications provide new forms to access cultural information and explore scientific phenomena in a game-based way. To do all this, a wealth of tools and IT based methods and concepts are provided for the different user groups involved, but the hypothesis of the authors is that there has not yet been an adequate connection between visitors and museum staff.

Based on that premise, this paper introduces MuViPlan as an interactive authoring environment especially addressing the collaboration between museum staff and visitors.

Museum Staff are enabled

- to archive scientific results

- to provide public access and different views of a wealth of information

- to build informative Web sites with features related to specific target groups

- to moderate forums and get feedback from interested visitors

- to configure installations and applications

- to provide templates for customized museum visits

- (to plan exhibitions).

Visitors are enabled

- to get a first impression of the museum and its contents

- to prepare for museum visits

- to customize (templates for) guided tours

- to document impressions and provide feedback

- to get in contact with museum staff and/or other visitors.

Other important groups such as marketing directors or sponsors are not considered within the scope of this paper.

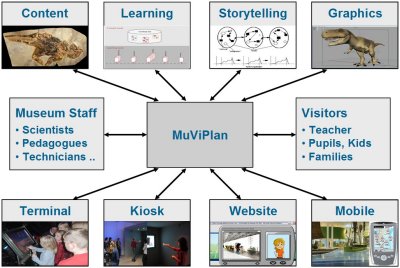

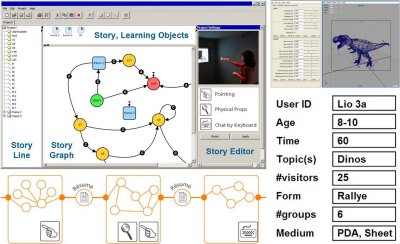

Fig 1: MuViPlan - Framework

Analysis

The most important aspects taken into account in the MuViPlan development process are illustrated in the upper part of figure 1: Content creation and management issues, Learning, Interactive Digital Storytelling and Computer Graphics.

Whilst content creation describes the process of transforming existing information (e.g. texts, pictures, artifacts or database entries) to multimedia content (e.g. Web sites), content management is responsible for archiving and administation of content.

Referring to archiving issues, the most challenging task – from a technicical perspective – concerns the heterogeneous terminology and classification schema of various application domains. On one hand, various museums provide information portals and content creation/management software for their individual domains; on the other hand the establishment of information brokers or domain-overlapping portals often is not easy or even possible. Therefore a lot of research effort (Vernon, 2004) and programs consider those semantic issues and try to build domain-independent guidelines and standards for archiving and accessing data (e.g. minerva, 2005).

CoreMedia based on client server technology, which provides modules for content creation, content administration, content publishing, media assets and digital rights management, is a typical example of popular content management software. Other examples for domain-specific CMS software are ADLIB Museum (relational database, archiving of artifacts/objects and corresponding metadata such as biographic data of artists, status, insurance value, location or links to related objects), and The Museum System™ (TMS offers a pure CMS software plus additional modules such as the authoring module eMuseum for building multilingual Web sites, guided tours in 3D environments or an on-line shop). Additor is an authoring environment based on client/server architecture, drag and drop principle that provides a WYSIWYG editor and uses open source software such as mySQL database or Apache Web server.

Similar to CMS, learning management systems provide methods, concepts and tools for structuring data, learning content (usually called learning objects or learning assets), and building learning courses. A typical architecture for a complete learning platform includes learneXact with a learning object storage repository and tools for the content authoring and content delivery processes. Underlying learning models for traditional learning courses are based on the different learning steps and phases (see Figure 2).

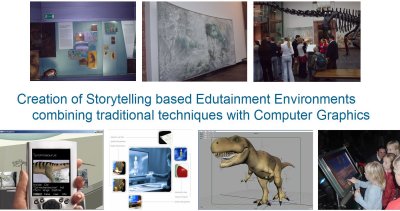

Fig 2: Learning courses and Storytelling based learning models

In order to build more exciting learning courses, many agree that the basic requirement is to bring in dramaturgic aspects (Thissen and Mödinger, 2004) and Interactive Digital Storytelling mechanisms (Hoffmann et al., 2005). As a result, suspenseful stories and course material with a suspense curve (see right part of figure 2) can be created, combining learning objects and units with a story model.

Since this idea is relatively new, there is as yet no proven benefit for its use within a museum context but possible impacts are being discussed in the museum community and are the topics of current research programs (Storytelling, 2005). The EU funded integrated project INSCAPE specifically addresses issues ranging from foundational storytelling research to authoring environments for the establishment of storytelling-based edutainment applications in different genres, e.g. film, theatre, cartoons, science-park or computer games.

Information and preparation material, primarily for teachers, in the form of stories are widespread on museum Web sites (see Museum of Tolerance, 2004), but interactive Web site applications with storytelling metaphors are rare (Johnson, 2004).

In fact, museums use stories and storytelling as new media for knowledge transmission and – similar to game based approaches – to enhance immersion and experience in learning environments. An example of this trend is provided by Educational Web Adventures (Eduweb, 2004): “Eduweb's mission is to create exciting and effective learning experiences that hit the sweet spot where learning theory, Web technology, and fun meet.”

Virtual galleries, interactive tours or 360° panoramas using different browser plug-ins (QuickTime, Macromedia Shockwave, Flash, ..) or 3D environments (VRML, Java 3D) placed on Web sites provide information and navigation environments to explore museums in a game-based way. In addition, virtual characters, sometimes in 2D comic-style (Cedy 2005) and sometimes as full 3D avatars, are used as virtual guides, guiding visitors (especially young visitors and kids familiar with computer games and 3D computer graphics) through virtual museums and exhibitions.

Apart from Web sites, high-quality 3D computer graphics are also used for animation and simulation purposes both for scientists in the museum and visitors fascinated by walking dinosaurs on a terminal in the Senckenberg museum (Feix et al., 2004) ,or becoming interactive explorers visualizing biological or physical phenomena (TNT, 2005).

Fig 3: Computer Graphics for animation and simulation of dinosaurs

MuViPlan Concept

MuViPlan endeavors to achieve two goals. On the one hand, MuViPlan aims to support museum staff preparing exciting museum services reaching a high variety of visitor groups. On the other hand, it aims to enable visitors to plan individual museum visits, customize available templates (stories, tours) and playing active roles in the global scenario.

Fig 4: MuViPlan - Scenario

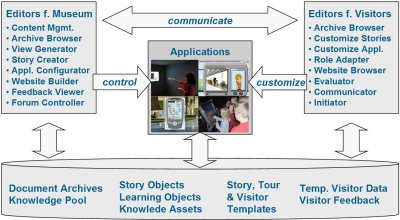

In order to achieve these generic goals, MuViPlan provides a bundle of editors and tools, which are partially located within an intranet (accessible to museum staff only) and partially realized as applets placed on the public Web site. Interfaces to the run-time applications and the content level are also available.

From the content perspective, all applications and services are built from traditional document archives, including object descriptions, metadata or related media and artifacts. As usual, scientists and curators enter data into the system and browse the archive(s) for their daily work. As far as possible, new outcomes of scientific research are included in the archive; otherwise scientists use individual tools and store the information separately – we call it the 'Knowledge Pool'. Both curators and museum educators are responsible for extracting appropriate information for exhibitions, applications and services. The extracted information, such as a PDF document, might be used 1:1 as information placed in the download area of the public Website. Any commonly used CMS described in the analysis section above would be sufficient to support this function.

Another more elegant model is to use the extracted information as knowledge assets and combine it with learning and storytelling paradigms. Thus, knowledge assets become learning and story objects which provide the foundation (of templates) for story-driven guided tours, chat-based terminal applications or services for the Web site (e.g. interactive stories, virtual museums or games). Finally, users (such as teachers) can access templates and customize stories and applications in order to plan their individual museum visits.

How Does It Work?

Scientists, for instance paleontologists in the Senckenberg museum in Frankfurt examining appearance and behaviour of dinosaurs, or art historians and analysts working at museums of art, primarily use traditional content management and archiving software described above. Specific tools such as complex databases for art diagnosis (Karagiannis, 2004) or 3D exploration tools simulating walking styles of dinosaurs (Sauer et al., 2004) may be used as well. MuViPlan's strategy is to establish interfaces to these tools (Content Management and Archive Browser) and provide additional editors enabling scientists to create different views of the results of their work (View Generator) and to extract knowledge assets as bases for stories (Story Creator) and other applications and services. Similar to the layout of a complex installation, software editors consist of two parts. On the left side, available data and features are listed in the 'source' area; these can be selected via drag-and-drop to the 'target' area in the right side.

Curators and museum educators plan the interpretation of individual artifacts, installations and exhibitions. Within the Story Creator, the central component/editor of the MuViPlan authoring environment, curators first choose content in the form of knowledge assets corresponding to the planned exhibition. In a second step, in collaboration with educators, appropriate media and interpretive aspects are considered, in order to build learning and story objects as the basis for story templates. These templates are used for guided tours or Web site applications.

From the pedagogic point of view, story models and templates for the different visitor groups (e.g. pupils of different ages) take into account curricula provided by teachers or ministries of education. As a second criterion, timing enormously influences the selection of story models and the establishment of templates for various applications. For instance, a school class visiting a museum needs guided tours or activities that take no more than 60 minutes. Another example concerns kiosk applications or complex interactive installations. If only one visitor can enjoy the application, time should be limited so other visitors can use it. Therefore, the Story Creator provides a timeline for both a complete story or tour and small parts of it (e.g. using a chat-system or 'playing' with a terminal). Then, the Application Configurator is used to define time limits and control periods at specific locations. Presentation forms (media, comic-like 2D avatars, gaming elements, etc.) are assigned to visitor groups' respective visitor templates. Likewise, the Website Builder is used to place stories and applications on the Web site and list different configurations for different users (visitors).

The Feedback Viewer is used to create feedback forms and analyse the results. This could happen semi-automatically. For example, feedback statistics could be created for all metric/measurable data, while museum staff (maybe a Web site manager, technician, pedagogue or curator) analyses free text feedback.

Web site managers also take the role of moderating real-time, on-line forums: The Forum Controller provides an entry point to the forum and offers the chance to communicate with on-line visitors or to delegate questions to curators and scientists who are willing to communicate with visitors. For example, such a on-line forum might enhance community-specific networks such as the dino-web network connecting several dinosaur museums and provide paleontologists an opportunity to get different perspectives and new ideas while communicating with domain-specific colleagues at other museums or with interested visitors.

MuViPlan enables visitors to become active parts of the museum visit instead of being passive consumers only. Apart from downloading information material from the Web site, a number of additional editors and features are provided in order to plan individual museum visits or use the museum (and its Web site) as third learning place:

- An Archive Browser implemented as browser-applet is placed on the Web site and enables on-line visitors to connect to document archives and browse all available information (views created by museum staff).

- Editors for Customizing Stories and Applications enable visitors such as teachers to adapt existing templates to their individual situation, including interests, background, age, time, etc. Hence, teachers could access the Web site during the preparation phase of a visit and register on-line. Then, parameters are filled within the editors and stored within a temporary visitor database. When the class enters the museum, the teacher produces an ID provided with the on-line registration and the terminals etc. are switched to the customized mode appropriate for that class.

- The Evaluator, Communicator and Initiator represent editors on the museum Web site to provide feedback (using feedback forms), to enter the on-line forum and discuss with other visitors or museum staff (as long as they are interested and have time for it) and to initiate new concepts by providing ideas, content or even services. For instance, pupils might develop little quiz-like games or create their own stories and place them on the Web site for other visitors.

Fig 5: MuViPlan – Editors

MuViPlan Prototype

MuViPlan concepts introduced within this paper have been realized in a prototype providing a comprehensive authoring environment to plan individual museum visits. Results of the multi-phase authoring process consider all phases of a museum visit: preparation, visit and post-processing. The following scenario describes the use of MuViPlan for creating a museum tour for a school class.

Once a story-based template for a tour is created, curators and (museum) educators can define different stations (locations, applications) for the tour and specify possible interaction metaphors for those applications, e.g. using a touch screen on a terminal system, a mouse, speech recognition, pointing gestures, physical props or a chat system using avatars and a keyboard as input device. A general question is, how much information and how many services are placed on the Web site, and how many applications are only available for visits in the museum? For example, views generated by scientists using special 3D modeling and analysis software (figure 5, upper right part) might be placed on the Web or on a terminal.

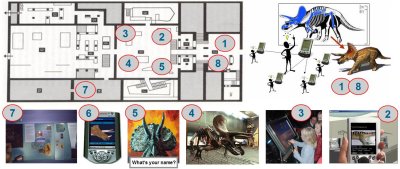

In a second step, teachers visit the Web site, log in as registered users and enter the MuViPlan ‘visitor mode’. Based on input parameters such as age of the pupils, duration of the visit, size of the class, focus topic(s), form of the visit (guided tour, individual exploration.. ..) or the media used (nothing, audio guide/headphones, PDA, paper worksheets, ..) MuViPlan searches the content-base and provides a list of appropriate visit types matching the user needs. The teacher selects one type - such as a tour in the group mode - and receives a preview of the tour providing a floor plan of the museum with all stations of the tour (see figure 6). Then, the teachers, using special interaction metaphors selected out of the list provided by the museum authors, can customize the tour by choosing specific tasks for the groups and information to be gathered at the different stations. All the input is saved with a unique ID in the database for temporary visitor data.

Fig 6: MuViPlan - Tour

Starting the visit, the class arrives at the museum entrance hall and the teacher enters the ID at the reception desk. Immediately, the system loads all relevant data, pupils (divided into groups) receive PDAs and/or paper worksheets, and the tours begin. Note that PDAs of the small groups are configured in different ways, providing separate routes, in order to avoid collisions at individual stations. Pupils stroll around, visit the different stations, try to collect as much information as possible, and work on solving the tasks the teacher has specified. At the end of the visit, the class comes together at the entrance hall (station 8), all PDA's or other equipment are put back on the loading stations, and all user interactions and collected info stored on the PDA are entered into the visitor database.

Back at school, the class visits the Web site of the museum again and loads its individual (produced) data. This data might be used to create a multimedia report placed either on the museum's or the school's Web site. Then, teacher and pupils have the chance to fill in feedback forms or describe their impressions and make suggestions for improvements. Similarly, they might enter the chat forum and try to find other pupils or on-line visitors to exchange impressions with, or try to contact museum staff for 'question and answer' sessions.

From the museum side, temporary visitor pathways data and feedback is (semi-automatically) analysed and taken into account for application improvements or extensions. For example, questions formulated by pupils at the chat-system (station 5 in the tour example) might address interesting aspects, in the best case to be considered in further scientific research, or at least to enhance the knowledge base of the chat system.

Finally, deletion of temporary class/visit-related data is triggered by the teacher or automatically caused by an expiry date imposed by the museum.

Conclusions

MuViPlan provides methods and concepts both to support museum staff preparing exciting museum 'services' for a large variety of visitor groups and to enable visitors to plan individual museum visits. The basis for customized story-driven tours or other applications comes from a knowledge pool and extracts knowledge assets, learning and story objects. As with archives, information brokers or museum networks, success primarily depends on the motivation of scientists and curators to provide knowledge to the public and to allow visitors to view their work. Furthermore, the creation of templates for different audiences (visitor classes) requires time and effort, especially for museum educators, in order to address relevant topics/content (e.g. corresponding to curricula at school) and to find appropriate interaction metaphors and (digital) media that will be fascinating for the different visitor classes. From the technical point of view, the most critical point concerns logistics and timing issues for tours (group mode, many visitors). Another issue is customized terminal applications with one screen that has multiple visitors in front of it: especially its technical preparation within authoring environments.

All these issues will be considered in further research of the Digital Storytelling department at ZGDV Darmstadt, e.g. within INSCAPE as a key project for interactive storytelling on the European scene. From a practical perspective, similar showcases, such as a mobile tour using PDAs and RFID technology at the Überseemuseum in Bremen, have shown the technical feasibility and visitor acceptance of these scenarios. Later on, MuViPlan plans to offer a bundle of services and applications which can easily be connected to the business side of museums – in addition to traditional guided tours or Web sites and museum eshops.

References

Cedy (2005). Museum for Kids – visiting the Mercedes-Benz museum with Cedy. Consulted January 30th, 2005 http://www.cms.daimlerchrysler.com/emb_classic/.

Eduweb (2004). Educational Web Adventures, consulted http://www.eduweb.com.

Feix, A.; Göbel, S.; Zumack, R. (2004). DinoHunter: Platform for Mobile Edutainment Applications in Museums. In: Göbel, S: (Ed.) et. al., Technologies for Interactive Digital Storytelling and Entertainment : Conference Proceedings TIDSE 2004. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York : Springer Verlag, 2004, pp. 264-269 (Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3105).

Hoffmann, A., Göbel, S., Schneider, O. (2005). Storytelling Based Education Applications. Accepted book chapter to E-Learning and Virtual Science Centers, Idea Group Publishing, Hershey, US, 2005.

Johnson, B. (2004). Beyond On-line Collections: Putting Objects to Work. In D. Bearman & J. Trant (Eds.) Museums and the Web 2004: Selected Papers from an International Conference. Toronto: Archives & Museums Informatics. 147-155. also available http://www.archimuse.com/mw2004/papers/johnson/johnson.html

Karagiannis, G., Daniilia, S. and Alexopoulos, B. (2004) An artworks documentation tool “ArtBASE”. Greek Patent No 20030100369 published 25/10/2004.

Minerva (2005). MINERVA network of Member States' Ministries to discuss, correlate and harmonise activities carried out in digitisation of cultural and scientific content for creating an agreed European common platform, recommendations and guidelines about digitisation, metadata, long-term accessibility and preservation. Consulted January 30th, 2005 http://www.minervaeurope.org/whatis/minervaplus.htm.

Museum of Tolerance (2004). Museum of Tolerance, New York. Teachers' Guide Web Site. Consulted March 15th, 2004 http://teachers.museumoftolerance.com/.

Opaschowski, Horst W. (2000). Kathedralen des 21. Jahrhunderts. Erlebniswelten im Zeitalter der Eventkultur. In B.A.T. Freizeit-Forschungsinstitut GmbH, Hamburg, Germa Press, 2000.

Sauer, S., Osswald, K., Göbel, S., Feix, A., Zumack, R., Hoffmann, A. Edutainment Environments. A Field Report on DinoHunter: Technologies, Methods and Evaluation results. In D. Bearman & J. Trant (Eds.) Museums and the Web 2004: Selected Papers from an International Conference. Toronto: Archives & Museums Informatics. 165-172. also available http://www.archimuse.com/mw2004/papers/sauer/sauer.html

Springer, J. et al. (2004). Digital Storytelling at the National Gallery of Art. In D. Bearman & J. Trant (Eds.) Museums and the Web 2004: Selected Papers from an International Conference. Toronto: Archives & Museums Informatics. 123-130. also available http://www.archimuse.com/mw2004/papers/springer/springer.html

Storytelling (2005). International Conference „Story telling in museum contexts. Innovative pedagogies to enhance personnel competence”, Turin, IT, February 4-5th, 2005. Consulted January 30th, 2005 http://www.fitzcarraldo.it/en/training/2005/storytelling.htm.

Thissen, F., Mödinger, W. (2004). Neue Wege im e-Learning durch den Einsatz dramaturgischer Elemente. In: Schleiken, Thomas Hg. (2004): Wenn der Wind des Wandels weht… Kooperative Selbstqualifikation im organisatorischen Kontext. München: Rainer Hampp, 2004.

TNT (2004). The Neanderthal Tools, consulted http://www.the-neanderthal-tools.org/.

Vernon (2004). Vernon Systems. Auckland, New Zealand. Consulted March 15th, 2004 http://www.vernonsystems.com/.

Cite as:

Göbel, S. and A. Feix, MuViPlan: Interactive Authoring Environment To Plan Individual Museum Visits, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2005: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 31, 2005 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2005/papers/gobel/gobel.html

April 2005

analytic scripts updated:

October 2010

Telephone: +1 416 691 2516 | Fax: +1 416 352 6025 | E-mail: