Stephen Brown and David Gerrard, Knowledge Media Design, De Montfort University, UK

Abstract

This paper identifies two opposing factors within the overall trend towards increased accessibility of museum collections on the Web: the need to make museum Web sites more attractive to non-traditional audiences and the need to ensure that accessibility is maximised for those with disabilities. The rapidly increasing availability of broadband creates opportunities for museums to create rich multimedia Web sites that can attract much wider audiences. Without careful design such sites can also reduce the diversity of potential users by creating barriers to access for disabled users. By analysing two recent award-winning sites, this paper shows how rich multimedia content can be designed to enhance accessibility, and, conversely, that 'text-only' sites may reduce the accessibility of a site while unnecessarily increasing costs. We conclude that in order to 'square the triangle' of diversity, access and accessibility, the solution lies in thinking in terms of improvements in overall usability, rather than simply responding to the concept of 'accessibility' as it is narrowly defined by laws and official guidelines. However, our ability to apply this thinking is constrained by the limitations of current accessibility assessment tools such as Bobby. We describe a reduced but key set of accessibility checks, suggest a set of heuristics for undertaking them, and illustrate their application upon the sites in question.

Keywords: broadband, access, diversity, accessibility, Bobby, heuristics, multimedia

Broadband

Public access to broadband is increasing rapidly (Aron and Burnstein 2003, Kim et al. 2003). For example, OECD figures (2003) show that at the end of 2003, seven years after the introduction of broadband access services, the number of broadband subscribers across OECD countries exceeded by a considerable amount that of subscribers to mobile, analogue and ISDN dial-up access services at the same stage of market development.

Broadband refers to the bandwidth of communications networks, i.e. their capability to transmit large amounts of data rapidly, measured in bits per second (bit/s). At the time of writing (January 2006) UK domestic users are typically offered broadband services ranging from 2-24 Mbit/s depending on the network technology, location and service provider, compared with the 64kbit/s bandwidth of an ordinary telephone line. A further significant difference between broadband and traditional dial-up services is that public broadband networks offer users fixed price/unlimited access to the Internet (although some broadband tariffs are based on data volume) via 'always-on' connections.

Fixed price access and faster, more reliable data transmission rates allow home-based users to spend more time on-line interacting with more bandwidth-hungry content such as video, audio, multimedia simulations, videoconferencing, without having to worry about call time charges (Bacsich & Brown 2002). The potential for museums of widely available public access broadband has already been noted:

With the number of UK households and small businesses adopting broadband now passing the 3 million mark, museums need to consider the approaches they can use to present curator's expertise to new audiences in engaging ways for broadband. (Blyth 2005)

Access and Accessibility

Demands for increased accessibility and a desire to diversify museums' visitor profiles have preoccupied the sector for many years. Traditionally museums and galleries have an important part to play in learning, access and social inclusion (Lawley 2003, Sandell 2003) and in the UK, as elsewhere, they are urged to achieve the widest possible access to their collections and activities and make full use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) to make their collections more accessible (DCMS 2000, MLA 2001).

The term accessible has two meanings in this context: widening access to embrace the socially excluded, and improving access for people with disabilities. Accessibility for the physically disabled presents a different set of challenges from widening social access. The difficulty is that highly engaging interactive multimedia experiences that make cultural heritage content more appealing and engaging are not necessarily the best format for people with various perceptual, cognitive and motor disabilities.

Although there is a growing body of literature on Web site accessibility generally (Paciello 2000, Clark 2002, Mueller 2003) and some evaluation of Web sites in the library sector (Ormes and Peacock 1999, Brophy and Craven 1999, Petrie et al. 2004), very little research has been done to evaluate the accessibility of on-line cultural heritage collections for either general or disabled users (Robinson and Terras 2005). However, a recent international survey of 125 museum Web sites revealed that the level of accessibility of such sites is not high. Only 30% of English museum sites and 20% of international ones passed a basic technical test of accessibility, and user trials found that visually and cognitively impaired users could only successfully complete 75% of very basic tasks on the Web sites, a third of the study's test users felt lost on at least one occasion, and completely blind people in particular found the sites difficult to use (Petrie et al. 2005).

Accessibility for disabled people is a challenge that museums cannot afford to ignore. Disability legislation in a number of countries (e.g. Australia, Germany, the U.K. and the U.S.A.) establishes rights of access to services for disabled people, with some legislation specifically recognising Web sites as a service. The challenge facing museum Web site designers therefore is to create sites that exploit the potential of broadband in such a way that users with a broad spectrum of abilities may benefit. Specifically, does use of rich multimedia of the kind enabled by broadband necessarily render cultural heritage Web sites less accessible?

We propose to examine this challenge using a case study approach based on two examples of recent award-winning Web sites. While selection of just two sites may be viewed as somewhat arbitrary, in the absence of specific information about visitors' reactions to museum Web sites, awards are one of the few clear indicators of success we have (Haley Goldman and Haley Goldman 2005), and they give us a sense of what peers regard as best practice. A wider survey might be more representative of current practice as a whole, but it would not necessarily tell us any more about best practice because there are plenty of pragmatic reasons why sites are less than perfect. Arguably the two we have selected can be taken as benchmarks against which others in this field may be measured.

Accessibility Assessment Tools

Accessibility assessment is often undertaken using the Bobby tool (e.g. Petrie et al. 2005), originally developed by the Centre for Applied Special Technology (http://www.cast.org/about/index.html). Bobby is built upon the W3C Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG V1.0, see: http://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG10/), which it uses both to discover definite accessibility problems within HTML code, and to flag areas where accessibility problems might occur for manual checking. Although Bobby provides an excellent starting point for assessing accessibility of broadband friendly Web sites, it suffers from a number of important limitations.

First, the list of checkpoints to be manually assessed is so long it is unlikely to be applied thoroughly in many cases. Secondly, it does not offer specific guidance on how to manually assess areas where accessibility problems might occur. Fortunately, Thompson et al. (2003) suggest a shorter list of practical checks to be undertaken once the purpose of a site has been perceived. These are largely based upon a subset of the WCAG V1.0 / Bobby checkpoints and are listed below (with their relationships to WCAG V1.0 checkpoints noted where they exist):

- Turn off browser images and see if the graphics have text equivalents (WCAG 1.1).

- If the page contains audio content, ensure that a text equivalent is available (WCAG 1.1).

- Change the font size (if possible) and assess if the page is still readable (WCAG 3.1 / 3.3 / 3.4).

- View the page at a screen resolution of 640 x 480 pixels and assess if the information contained is still accessible.

- Examine use of colour. Is it used exclusively to convey information? If inadequate colour contrast is suspected, investigate this by printing the page (WCAG 2.1).

- Tab through the page to see if all links / form controls are accessible without a mouse (WCAG 9.4).

- Use Jaws or an equivalent screen reader and observe if the information contained within the page is still available. Also, note if a 'skip navigation' link is present to speed up use with a screen reader (WCAG 1.1 and 5). (Thompson et al. 2003)

Thirdly, the WCAG V1.0 guidelines are a little confusing when it comes to audio and video. They suggest that 'equivalent alternatives' to such content should be provided, and that in the case of 'time based' content such as video, the text version should be synchronised with the content it describes. Where descriptions of auditory events in video are concerned, they refer to 'captioning', but also use the term 'text transcript', a very different term that implies a text version of speech only, not sound effects, music, etc. Finally, regardless of the exact meaning of the WCAG V1.0, Bobby is incapable of assessing how well a text transcription describes a piece of media, how well synchronised it is, or how useful in general audio tracks are to visually impaired users, or video and animation to hearing impaired users.

Methodology

Thompson et al. suggest that their distilled shortlist provides a good indication of the overall accessibility of a Web site, so a decision was taken to use it for a general accessibility overview of the selected sites, but with two minor alterations:

- When poor colour contrast was suspected, rather than printing it we 'grabbed' the screen in question and 'desaturated' the colour from it using Adobe Photoshop.

- Rather than using Jaws to assess screen reader accessibility, we used the free Firefox screen reader emulation software Fangs, available at: http://sourceforge.net/projects/fangs/

The intention behind these accessibility checks is to assess the pathways to the rich media content contained within the Web sites. After all, the accessibility or otherwise of broadband content itself is irrelevant if a disabled user can't actually find or reach it in the first place. In addition, however, we have supplemented them with further checks that focus specifically on the 'broadband friendly' content itself. These are outlined below, with relationships to the WCAG V1.0 checkpoints noted once again. First, we ran manual checks upon interactive content provided by 'client side scripting' (such as dynamic page elements that respond to user-driven events like mouse clicks, dragging and dropping and so forth) to assess:

- whether the successful running of any scripts present was essential to the understanding and use of the page (WCAG 6.3).

- whether any alternatives to scripts were provided (WCAG 6.3).

- whether the scripts were dependent upon device-specific event handlers such as mouse clicks and movements (WCAG 6.4).

Regarding rich, 'broadband friendly' multimedia content, the WCAG V1.0 checkpoints state that a 'text transcription' of any rich multimedia content such as audio, video or animation is sufficient to make such media elements accessible. Therefore, the bottom line accessibility analysis tasks applicable to broadband friendly media are:

- to check for the presence of such text transcriptions (WCAG 1.1)

- to make a general assessment of how well they support the elements they describe. Is it possible to ascertain the meaning of the multimedia element using only the transcription, or by using it in conjunction with the transcription? Or does it leave out information that is contained in the multimedia element (perhaps in images, sounds etc) , material that is essential to its understanding?

However, there are other methods that can be used to make multimedia content accessible. According to the National Centre on Accessible Information Technology in Education, three important techniques for improving multimedia accessibility are captioning, audio description and allowing navigation using a keyboard (http://www.washington.edu/accessit/articles?146). A closer reading of the WCAG V1.0 supports the first two of these techniques by suggesting that, if the multimedia element to be described is time-based, the description should be synchronised with the playback (i.e.: the text transcription should be usable alongside the multimedia element itself). We therefore completed our assessment by implementing the following checks:

- were textual descriptions of time-based media synchronised with the elements they described? (WCAG 1.4).

- if video captions were included, did they only contain a synchronised transcript of dialogue, or did they indicate the presence of other meaningful sounds such as music or sound effects (as defined by Clark 2004)?

- was a version of the video with an audio description offered? Audio description provides an extra narrative voice that describes what users would observe if they could see the presentation clearly (Clark 2001).

(It is worth noting that, because both of the techniques described above take a high degree of skill to implement properly, merely checking for the presence of such augmentation of rich media is no guarantee of accessibility. However, it does offer some indication of intent, and can be empirically measured.) We also tried to access rich media content by 'tabbing through' it with the keyboard alone. This is essentially the same check as 'tabbing through' the Web-page pathways to the multimedia: we merely continued the process to attempt to access multimedia elements such as Flash animations, video and sound clips using the keyboard alone.

The Making the Modern World Web site (http://makingthemodernworld.org) was developed by the Science Museum, London. It is aimed at students, teachers, and more general audiences interested in the history of science and technology and is intended to "show how online learning materials could be created to increase access to and interest in science and history education." (Blyth 2005: 208).

The site comprises 5 main sections:

- Stories Timeline

- Icons of invention

- Everyday life

- Guided Tours

- Learning modules

The user interface is highly visual, employing "text and image, interactive maps, technical deconstructions, montage, mini-documentary, [and] dramatic reconstruction" (Blyth 2005: 209). It received the Museums and the Web Best of the Web award in 2005 particularly for the exciting and innovative use of broadband technologies within the site design.

The transport archive Web site (www.transportarchive.org.uk) was developed by a consortium led by Leicestershire County Council. It aims to provide integrated access to a number of disparate collections and archives relating to major transportation developments in the UK: the Great Central Railway, the Bridgewater and Manchester Ship canals, and the development of British aviation at Filton, Bristol. It too comprises 5 main sections:

- Gateway

- Canals

- Railways

- Aviation

- Learning zone

Although less multimedia rich than Making the Modern World, it is essentially a picture based site, using multimedia, timelines and interactive maps. It received the UK National Library for the Blind Visionary Design Education Award in 2004 for outstanding efforts in ensuring content is accessible to visually impaired people. As the focus of this investigation regards accessibility of broadband friendly interactive elements, we chose to analyse four sections of Making the Modern World that contained rich media and/or highly interactive content:

- A rich media scene entitled Silent Spring and the Story of DDT available at: http://www.makingthemodernworld.org/stories/the_age_of_ambivalence/02.ST.06/?scene=2.

- A rich media scene entitled The Atomic Age, available at: http://www.makingthemodernworld.org.uk/stories/defiant_modernism/04.ST.02/?scene=4.

- A rich media scene entitled Puffing Billy, available at: http://www.makingthemodernworld.org.uk/stories/the_age_of_the_engineer/01.ST.04/?scene=2.

- The interactive Stories Timeline available at: http://www.makingthemodernworld.org.uk/stories/ .

However, as we needed to assess the 'pathways' to such rich media elements, we also undertook checks on the path from the site homepage to the first of the areas listed above, starting with the 'most obvious' path and switching tactics where necessary. We also recorded the pathway we had to take and any barriers that caused a switch of tactics.

Similarly, we focused our assessment of the accessibility of Three Centuries of Transport on three areas that contained broadband friendly multimedia and interactive content:

- The Aviation Multimedia page, available at: http://www.aviationarchive.org.uk/multimedia/index.php.

- Interactive Ordnance Survey Maps of the Great Central Railway, available at: http://www.railwayarchive.org.uk/map/osIndex.php.

- The Canal Archive Timeline, available at: http://www.transportarchive.org.uk/timeline.php?l=t

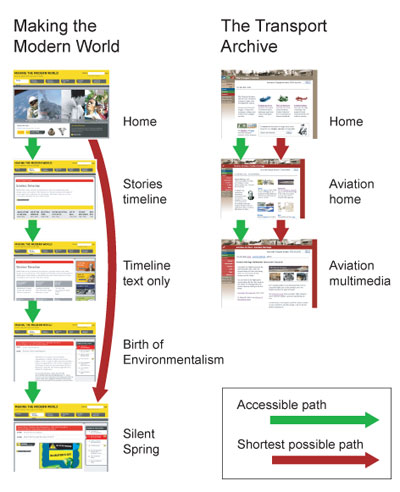

Given that the Transport Archive is an image archive rather than a museum site, we also assessed how accessible the site search engine was by applying our checks to a search for Nottingham Victoria station, as well as undertaking a pathway assessment as per the Making the Modern World site. The results of the pathway analysis are summarized in Figure 1.

Fig 1: Pathways to multimedia content in the two Web sites

Findings

A systematic report of the findings point-by-point, site-by-site results is available in a lengthy and repetitious list (see: http://kmd.dmu.ac.uk/research/MuseumSiteAccessibilityReviewData.xls). For clarity and brevity we have summarised the results under 6 headings.

1. Compositions of multimedia are inaccessible

This central pitfall of multimedia occurs in both sites to some extent, though perhaps the best example is in Making the Modern World's rich media content on the atomic bomb: an audio track featuring the testimony of key protagonists is read by actors to add drama and authenticity to the scene. Rich audio content of this sort is extremely appropriate for partially sighted users, but unfortunately in this case it is locked within a Flash movie that is hard or impossible for them to access, so they might have to make do with listening to a disembodied screen reader work its way through the 'text-only' version.

2. Individual, non-augmented media channels are inaccessible

In both sites there is simply less information available to a lot of disabled users than there is to other users. For example, the Transport Archive's text components often contain direct references to information held in the images, and are thus reliant upon the users being able to see the images to fully comprehend them. Similarly, the soundtrack of the final approach of the last ever Concorde was highlighted specifically by the judges at the National Library for the Blind awards for being wonderfully evocative. Perhaps hearing impaired users might also have been enraptured by the conversation between the pilot and the control tower, if it had been captioned? The "text-only" versions of Making the Modern World's rich media scenes contain merely the same short captions that are used in the Flash versions. As the reference point for the caption text has been removed, the text often becomes incomprehensible.

3. Providing accessibility does not just mean including a text-only version.

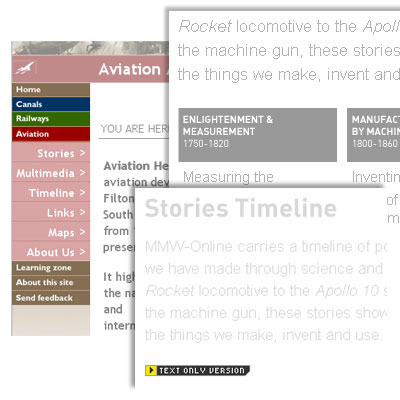

To its credit, Making the Modern World includes numerous 'text-only versions' of its rich media scenes, at least ensuring that a lot of the information contained in the site becomes accessible to visually impaired users. However, the Flash-based animated content is already largely accessible to users with hearing and motor-skill impairments, who thus don't need a text-only version. In spite of this, an unfortunate combination of factors prevents easy keyboard-only access to the Flash movies either in Firefox or Internet Explorer: content that is otherwise usable by visitors with motor-skill impairments cannot be reached. Perhaps this situation (illustrated in detail in Fig. 2) is the result of thinking in terms of solving all 'accessibility issues' by including a text-only version?

Use of a catch-all text-only solution is endemic within Web design and is by no means exclusive to the Making the Modern World site. It is a distinct possibility that confusing terminology on the part of the WCAG V1.0 has exacerbated this situation.

Fig. 2: "Text-only" version is the only accessible option for motor impaired users who could use the rich media scene

4. If 'alternative versions' are necessary, put them in an accessible place

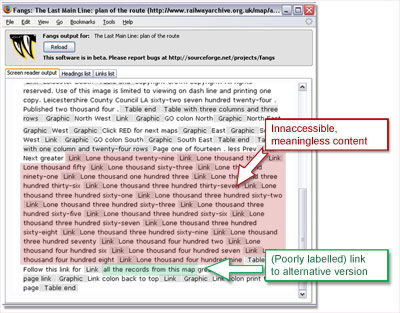

This issue manifests itself most notably in the Great Central Railway JavaScript/DHTML interactive maps of the Transport Archive. Scripting is used to provide interactive content, but to conform to the WCAG V1.0, an extra template was added to the design to create an alternative version that grouped content geographically in the same way, but which didn't need a mouse or a JavaScript enabled browser to access it. Unfortunately, the link to the extra template was placed at the very bottom of the map pages, so that users have to wade through all the content they can't use- on every map- to get to it. Fig. 3 shows Fangs output illustrating just how unpleasant access to the alternative version of the map content is.

Fig 3: Fangs output of poorly accessible link to alternative version in screen reader

5. Using images to format text is inaccessible

Both Making the Modern World and Three Centuries of Transport use images for text in some of the most important links, meaning that key parts of the interface do not resize with the rest of the text. A particularly striking example of this is the small but crucial 'text-only version' link in Making the Modern World. Arguably when relying heavily upon transcripts for accessibility, the one link above all others that ought to be resizeable for visually impaired users is the one to the text-only version.

Also, the 'text-only version' of the Making the Modern World Story Timeline contains important link/headings in the form of non-resizeable text in images. A montage of all of these transgressions (from both sites) is contained within Fig 4: the images were captured with the text at the 'largest' setting in Internet Explorer.

Fig 4: Montage of 'text in images' transgressions in both sites

6. Out of step

None of the video available in either of the sites contains captions or audio descriptions, even though the clips are generally very short and contain little dialogue, and in spite of free captioning software being readily available (e.g. http://ncam.wgbh.org/Webaccess/magpie/). Such software can create captions that work in Windows Media, QuickTime and Real Player, and the caption text could also have been used to augment the text in 'text-only' versions. Also, Flash has strong support for animated text, so if a short video clip is to be embedded in Flash as part of a rich multimedia presentation, why not caption it?

Synchronisation of textual alternatives in captions and voiceover is a WCAG V1.0 recommendation which, if adhered to and handled skillfully, can make rich media rich for everyone. So why even consider broadband content, video and animation 'inaccessible' and send disabled users to the text-only version? Perhaps fewer Web sites would do so if the WCAG V1.0 had not included the terms 'transcript' and 'text alternative'?

Discussion

These themes raise some important issues for the Web design community: Why is it that, despite extensive guidelines and checklists, cultural heritage Web sites in general, and even those regarded as exemplars of good practice, still exhibit significant accessibility issues? Is it that professionals in this field are uncaring? Or unaware of their legal obligations, or technically inept? Highly improbable on all counts. Perhaps what we need are more easily applied heuristics that encourage designers to really consider the accessibility problems in their designs, rather than the 'tick-lists' that tools such as Bobby provide.

Does 'accessible' have to mean a text-only version? We have seen how a text-only version can be a poor substitute for the rich information content of Flash media, but care needs to be taken when creating multimedia to ensure that rich composite media components can also be accessed individually by users with particular needs. There is no such thing as an average disabled person, so we need to think about different kinds of needs and how they might be met both individually and in combination.

We have also seen how well thought out media can be rendered inaccessible to some users by virtue of the Web site structure and the characteristics of the physical interface. The guiding principle here seems to be 'if something is worth doing, it's worth doing in more ways that one.' So provide multiple media channels as well as multimedia; for example, pictures and audio as well as pictures with audio. Structure and group the same content in different ways so that people with different abilities can access structures that most closely match their needs; for example, if you have links to audio tracks throughout the site, also collect the links together on a single page so that visually-impaired users don't have to wade through the whole site to find them all. Make sure that users with different abilities are not prevented from accessing parts of your site by problems with the interface. For example, make sure your navigation works just as well from the keyboard as it does with a mouse.

Does doing things in more than one way mean that accessible Web sites will cost more? Well maybe; as so often, it all depends. Splitting multimedia composites into their constituent parts need not be particularly costly. Captioning and/or transcribing video is more expensive, but has the added advantage that it helps search engines to crawl and index the video content, so more people will be able to find it more easily. Creating rich written or spoken descriptions of visual material can be very time consuming, but in this case perhaps we should be tapping into the voluntary networks that already exist, for example, to create 'talking books.'

The idea of captioning still and moving pictures raises an issue about the range of fields available in metadata schema such as Dublin Core. We already have a 'description' field, but, as we have seen, if this field merely reproduces the text that was already associated with the picture, then the visually impaired will be disadvantaged. We might expect a 'visual description' field to differ from the normal 'description' field. For example, a picture of an iconic kettle design might have accompanying text that names the designer and the originating design studio and mentions the design influences it draws upon. A visual description might describe its appearance in more detail and the context within which it appears. Anyone who can see the picture would find the visual description redundant. Anyone who could not see the picture could use the visual description to make sense of the ordinary description.

Do we need any other tools to help us assess and design accessibility? In this paper we have argued that WCAG V1.0 based tools such as Bobby provide an excellent starting point, but they need to be supplemented by other manual methods, and these in turn need to be short and easy to use by busy designers. The heuristics offered by Thompson et al. go some way to providing an answer, but we believe that they need to be extended in the way we have suggested to make them fully relevant to broadband friendly multimedia.

Conclusions

So what are the implications of broadband for museum Web site design? Public access to broadband is growing so rapidly that museum Web designers are already developing sites that exploit the high bandwidth and 'always on' characteristics of broadband through rich interactive multimedia. Such sites have the potential to be more appealing and engaging than static 'show and tell' sites, thus attracting wider audiences. But widening access also includes increasing accessibility for disabled people. We have seen how multimedia can both enhance and inhibit accessibility, depending on how it is designed; that provision of simple text-only versions does not necessarily enhance accessibility and may even be an unnecessary expense.

It has been argued elsewhere (Vetch 2004) that in order to 'square the triangle' of diversity, access and accessibility, the solution lies in thinking in terms of improvements in overall usability, rather than in simply responding to the concept of 'accessibility' in the terms by which it is articulated by laws and official guidelines.

Our findings concur with this view, but to operationalise it we believe that we need additional tools and ways of thinking. In particular, we need to act on the following:

Part 1: See if you can get to the multimedia

- Turn off browser images and see if the graphics have text equivalents (WCAG 1.1).

- If the page contains audio content, ensure that a text equivalent is available (WCAG 1.1).

- Change the font size (if possible) and assess if the page is still readable (WCAG 3.1 / 3.3 / 3.4).

- View the page at a screen resolution of 640 x 480 pixels and assess if the information contained is still accessible.

- Examine use of colour. Is it used exclusively to convey information? If inadequate colour contrast is suspected, investigate this by printing the page or 'grabbing' the screen in question and 'desaturating' the colour from it using a paint package. (WCAG 2.1).

- Tab through the page to see if all links / form controls are accessible without a mouse (WCAG 9.4).

- Use Jaws, an equivalent screen reader or screen reader emulation software such as Firefox Fangs, available at: http://sourceforge.net/projects/fangs/ and observe if the information contained within the page is still available. Also, note if a 'skip navigation' link is present to speed up use with a screen reader (WCAG 1.1 and 5).

Part 2: See if you can use the multimedia

- Assess whether the successful running of any scripts present is essential to the understanding and use of the page (WCAG 6.3).

- Assess whether any alternatives to scripts are provided (WCAG 6.3).

- Assess if the scripts are dependent upon 'device specific event handlers' such as mouse clicks and movements (WCAG 6.4).

- Check for the presence of text transcriptions (WCAG 1.1).

- Make a general assessment of how well they support the elements they describe. (Is it possible to ascertain the meaning of the multimedia element using only the transcription, or by using it in conjunction with the transcription? Or does it leave out information that is contained in the multimedia element (perhaps in images, sounds etc) that is essential to its understanding?)

- Assess if text transcriptions are synchronised with the element they describe in the case of time-based media (and if so, how effective they are at conveying the meaning of the element). (WCAG 1.4).

- Check if video has been captioned to include relevant sounds, music and so forth as well as dialogue.

- Is a version of the video with an audio description offered? Audio description provides an extra narrative voice that describes what the user would observe if they could see the presentation clearly.

References

Aron, D. J. and D.E. Burnstein, (2003). Broadband Adoption in the United States: an Empirical Analysis. Social Science Research Network http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=386100 Accessed 15/01/06.

Bacsich, P. and S. Brown (2002). Broadband Technologies for Learning and Teaching Off-Campus. TechLearn Technical Report, York: JISC Technologies Centre.

Blyth, T. (2005) Curating for Broadband. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web, Selected papers from Museums and the Web 2005. Toronto: Archives and Museum Informatics. 205-212. Also available http://www.archimuse.com/mw2005/papers/blyth/blyth.html

Brophy, P. and J. Craven (2003). Non-visual Access to the Digital Library (Nova): The Use of the Digital Library Interfaces by Blind and Visually Impaired People http://www.cerlim.ac.uk/projects/nova/index.php Accessed 30/11/05

Clark J. (2001). Standard techniques in audio description. http://www.joeclark.org/access/description/ad-principles.html Accessed 21/12/05

Clark, J. (2002). Building Accessible Websites. Indianapolis: New Riders.

Clark J. (2004). Best practices in online captioning. http://www.joeclark.org/access/captioning/bpoc/ Accessed 21/12/2005

Department for Culture, Media and Sport (2000). Centres for Social Change: Museums, Galleries and Archives for All. London: DCMS.

Haley Goldman, M. and K. Haley Goldman (2005). Whither the Web: Professionalism and Practices for the Changing Museum. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2005: Proceedings. CD ROM. Archives and Museum Informatics, 2005. Also available http://www.archimuse.com/mw2005/papers/haleyGoldman/haleyGoldman.html

Kim, J., J.M. Bauer and S.S. Wildman (2003). Broadband Uptake in OECD Countries. Paper presented at the 31st Research Conference on Communication, Information and Internet Policy. Arlington: VA http://tprc.org/papers/2003/203/Kim-Bauer-Wildman.pdf Accessed 15/01/06.

Lawley, I. (2003) Local authority museums and the modernizing government agenda in England. Museum and Society, 1(2) 75-86.

MLA (2001) Renaissance in the Regions; A new vision for England's museums. Resource: The Council for Museums Archives and Libraries http://www.mla.gov.uk/resources/assets//R/rennais_pdf_4382.pdf Accessed 22/02/06.

Mueller, J. (2003). Accessibility for everyone: unde rstanding the section 508 accessibility requirements. Berkeley: Apress.

National Centre on Accessible Information Technology in Education Web site: What is rich media and how can I learn more about its accessibility? http://www.washington.edu/accessit/articles?146 Accessed 21/12/2005.

OECD (2003). ICCP Broadband Update. Working Party on Telecommunication and Information Services Policies. http://www.oecd.org

Ormes, S. and I. Peacock (1999). Virtually Accessible to All? Library Technology, 4 (1), 17-18.

Paciello, M. (2000). Web accessibility for people with disabilities. Lawrence: CMP Books.

Petrie, H., N. King, F. Hamilton and M. Weisen (2004). Disabled people and the Web: Web accessibility in the cultural sector. Paper presented at the EVA (Electronic Imaging and the Visual Arts) Conference, London, 29 July 2004.

Petrie H., N. King and M. Weisen (2005) The Accessibility of Museum Web sites: results from an English investigation and international comparisons. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.): Museums and the Web 2005: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives and Museum Informatics, 2005 http://www.archimuse.com/mw2005/papers/petrie/petrie.html Accessed 08/12/2005.

Robinson, A. and M. Terras. (2005). Come on Let's Go: Access, Accessibility, and Digital Image Collections. Lancaster: Digital Resources for the Humanities Conference 4-7 September 2005. Abstracts 41-42.

Sandell, R. (2003). Social inclusion, the museum and the dynamics of sectoral change. Museum and Society, 1 (1) 45-62.

Thompson T., S. Burgstahler and D. Comden (2003). Research on Web Accessibility in Higher Education. Information Technology and Disability, 9 (2) December 2003 http://www.rit.edu/~easi/itd/itdv09n2/thompson.htm Accessed 16/12/05.

Vetch, P. (2004) Accessibility Challenged: Enhancing usability to provide universal access to complex Humanities Web resources. Newcastle upon Tyne: Digital Resources for the Humanities Conference. Abstracts: 42-43.

Cite as:

Brown S. and Gerrard D, Squaring the Triangle: The Implications of Broadband for Access, Diversity and Accessibility in Museum Web Design, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2006 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/brown/brown.html