Karen Elinich, The Franklin Institute Science Museum and Paul Sparks, Pepperdine University, USA

Abstract

Historic documents present a rich social legacy and should be available to all. On-line retrieval of documents is a growing solution, but access creates many problems. One important problem is interface, or how exactly one interacts with a digital representation of a document. Inattention to interface issues such as navigation, image quality, ease of use can make the experience less than satisfactory. Additionally, capturing the context of the document is a particular challenge for on-line presentation.

We explore various Web-based historic document retrieval sites and review them with an eye towards useful interaction design. Using existing established and accepted Human-Computer Interface (HCI) principles, we systematically identify the most common design flaws and omissions. We also identify positive interface traits and possibly map our findings to the success or popularity of the systems.

At the heart of our search is a desire to find ways of presenting documents that are at once accessible and rich. We search for sites that convey texture and age and condition. We hope to find sites that allow manipulation of the document in intuitive ways. We hope to discover best practices around maintaining the document in context of its covering and time period. And we hope to find compelling ways to personally annotate the documents in unobtrusive but meaningful ways.

It is hoped that the analyses of a variety of sites will yield a set of issues to avoid and key features to include, information useful to museums beginning document retrieval programs.

Keywords: museums, books, documents, usability, interaction

Introduction

On-line museums and archives provide public access to primary source materials in a variety of ways. This analysis is an attempt to understand the range of approaches and to identify practices that facilitate interaction in meaningful ways.

For a decade, museums and archives have been selectively presenting artifacts from their collections. The selection process has been driven by a number of factors. In many instances, decisions were made based upon expediency, with little time and attention paid to user interaction with the artifacts. Only recently has usability become a prime consideration.

While museums also provide on-line representations of three-dimensional artifacts, the focus of this investigation is two-dimensional; in particular, this investigation considers the digitization and presentation processes of historic multi-page documents, including books, manuscripts, and monographs. Multi-page documents present unique challenges for on-line interaction. The easiest and most expedient solution is to present each page as an individual artifact. While the pieces may add up to be a reasonable approximation of the whole, the experience ultimately cheats the user of the real power of interaction with the assemblage. Instead, museums and archives must find ways to enable users to interact with authentic representation of multi-page documents on-line.

The five Case Studies below represent the authors' collected efforts over three months to locate freely accessible on-line presentations of historic multi-page documents. While the investigation was thorough, it may not have been exhaustive. It is safe to conclude, however, that the number of museums and libraries currently undertaking such presentation is small.

Development of Evaluation Criteria

Conducting the initial case studies prompted a formative list of criteria. This list was expanded in several ways to provide the final evaluation criteria. Criteria were expanded to include features encountered with each new case, and the list was checked against guidelines offered by usability experts Krug (2000), Nielsen (1999).

Criteria fell into four natural categories: fidelity, interaction, facilitation, and technical issues. Fidelity covers all issues relating to authentic representation of the book or manuscript. The experience of interacting with the document within the on-line space was captured with interactivity criteria. Facilitation refers to enhanced ways of interacting with the content made available by computers, such as searching and usage statistics. Finally, there are several simple technical issues that potentially influence the experience for the user.

The overall page turning experience is perhaps most effectively determined by the fidelity of the experience. High quality graphics are key to providing visual fidelity. Visual representation can range from lifeless computer generated text to high resolution images which capture the texture, imperfections and soul of the document viewed. Believable animation is another element of fidelity. Can pages be turned with minimal lag time, supporting distorted views as the page is turned? Adding sounds which enhance the visual cues can also add to the fidelity as well. Lighting is key for observing actual documents and can also be incorporated for a more realistic experience on-line. Finally, cues illuminating the larger, wider context of the document can greatly enhance the fidelity of the experience.

High quality interactions are also key to a rewarding on-line experience. The following items with explanations comprise the key elements of high quality interaction. User-friendly page navigation is key and requires user interactions that are easily learned and remembered. Other interactions should be considered, such as opening and closing books, flipping, and 3-D manipulation. Good interaction is marked by ease of learning, easy start-up, and re-use on subsequent visits, and obvious clues to what is clickable. Good interaction also takes advantage of conventions. Allowing users to accomplish their goals simply with uncluttered functionality leads to high user satisfaction.

facilitation is a catch-all term used to capture all capabilities typically not associated with a physical book. For example, word searching has become popular with Web browsing, and it is clearly not possible with a physical book. One can scan but not search for particular words. Creating anchor points, bookmarking sections, or even annotating the document would not be done to cherished historical documents but is possible with computers.

More subtle tools enable systems to track and display document age and usage data. The ability to magnify pages is also included. Other facilitation interactions include synonym or thesaurus searches.

Technical Issues were a late addition to the criteria matrix, as a response to the real circumstances of this review. Reviewing the systems kept raising unexpected issues such as additional software requirements - from plug-ins to full application downloads - not to mention platform issues: Macs and PCs were inconsistently supported. Finally, the issue of accessibility must be considered in this analysis. These criteria were abbreviated and formed into a matrix and used to evaluate the best of electronic document viewing.

| Fidelity | Interaction | Facilitation |

|---|---|---|

|

High quality visuals Book sounds Believable animation Allows Lighting Changes Provides Context |

Natural page turning Ease of learning Usefulness Satisfaction Other manipulations |

Allows word searching Provides magnification Allows bookmarks Usage and comments Other data |

|

Technical Issues:

Additional software/hardware required, accessibility, and platform.

|

||

Table 1: Evaluation Criteria. Derived from Krug (2000) and Nielsen (1999).

Case Study: The British Library

The British Library created its on-line gallery so that users can "leaf through 14 great books and magnify the details" (www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/ttp/ttpbooks.html). The collection includes interactive representations that mirror the experience of turning the pages of a book. Browsing through the books requires the use of a Shockwave plug-in. The user ‘grabs’ pages and drags them across the screen in order to reveal the next page (Dutton, 1998).

Interestingly, the Library chose to provide ‘alternative non-Shockwave versions’ for three of the books in the collection. These three books provide an excellent case study. In particular, the Golden Haggadah, a lavishly illustrated Hebrew prayer book, is presented using both techniques. Using the Shockwave plug-in, the user opens the heavy leather book - from the left, because Hebrew is written from right to left - and turns the pages, pausing to magnify areas of interest in the illustrations. In the non-Shockwave version, a photograph of each two-page spread appears on each of a series of Web pages. The user also has the option to click open a larger version of each image. In both techniques, the user has the option to play an audio track (Shigo, 2003) which offers a curatorial perspective on the Haggadah. In the non-Shockwave version, each two-page spread also includes text-based interpretive commentary.

The Shockwave-based version is gorgeous. The on-line experience of turning the pages of the Haggadah is as close to the real as an average user is ever likely to come (Ojala, 2003). In that context, the British Library has provided an invaluable service to audiences around the world.

Fig 1: The British Library’s On-line Library. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/ttp/ttpbooks.html

Usability Analysis

The fidelity of these books is quite uncommon. The books appear on the screen like the originals with high quality graphics that show the texture and even the stains and defects on each page. This is perhaps the feature which most sets this piece apart from others studied. Page turning shows the distortion of page contents realistically and is so smooth that users get the sense of really paging through the document. There appears to be no control over the lighting of the text or the context in which the text exists.

Interaction is very tactile with the help of the mouse. The sense of turning a page is clearly captured, but the interaction can be confusing. More often than not, the page drops back into place without turning, making the experience somewhat frustrating until that mouse skill is mastered. Still, the program is easy to learn to use and provides much satisfaction for the user. Not only can users review by paging, but they also have a slider bar making it easier to jump to another section.

Word searching and the ability to bookmark were not available; however pre-programmed comments were available in audio on most pages, as well as high-resolution partial page magnification. The rare feature of image rotation was available where appropriate (sideways graphics).

While this is an extraordinary site, there are a few technical issues. The piece requires that users download the Shockwave plug-in and enable pop-ups in the browser to operate correctly. The instructions for setting this up are clear but may turn less technical users away from a rewarding experience. The interaction runs equally well on major platforms. Accessibility is a problem only in the full multimedia version which is inherently visual and does not seem to have even the most common image metatags encouraged by accessibility guidelines. However, by having two versions, the British Library exemplifies one solution to a very tricky problem.

Case Study: The Franklin Institute Science Museum

The Franklin Institute Science Museum holds a large collection of two-dimensional artifacts related to its annual scientific Awards program (www.fi.edu/case_files). Since 1824, the Institute's Committee on Science and the Arts has considered nomination cases for acknowledgement of achievement in science and technology. These nomination cases result in a documentary archive. After seventy-two years, the documentation becomes accessible for scholarly access.

Many of the documents in the files are single-sheet-correspondence, applications, patents, schematics, etc. Included in many files, however, are multi-page documents related in some way to the work of the nominee. For example, the case file for William S. Burroughs contains two ‘brochures’ related to the American Arithmometer Company which he established. These brochures from 1897 offer a fascinating glimpse into the business of the Industrial Revolution. One piece is a sales brochure, and the other is an operator's instruction manual. The Institute's presentation maintains the integrity of the hands-on encounter with the brochures. Through a Flash-based technique, users can now turn the pages of the brochures and pause to magnify areas of particular interest. The on-line interaction with the artifact closely parallels a real, physical encounter (www.fi.edu/case_files).

Other case files contain multi-page documents which have been presented in the same way. For example, the case file associated with Madame Marie Curie contains a copy of Le Radium, her landmark 1908 manuscript, which is printed in French. On-line user interaction with Le Radium may actually surpass the physical experience because segments of the manuscript have been translated into English. With the click of a mouse, the document translates the key segments. If users prefer not to see the English translation and to maintain the authenticity of the original source, then they simply ignore the translation option.

Does this intervention enhance the usability of the artifact or does it intrude on the authenticity? The answer is unclear. As long as the original manuscript presentation is maintained and the translation exists only as a supplemental feature, then the integrity seems to be intact. Still, technology enables the museum to impose meaning in the presentation of the manuscript, and that may be an intrusion. The ability to translate Curie's French to English is similar to the option to listen to an audio commentary about the history of the Haggadah. These features are enhancements made possible by technology, but may ultimately detract from real interaction with primary sources.

Fig 2a. Le Radium in original French. http://www.fi.edu/case_files/curie/le_radium.html

Fig 2b. Le Radium with partial English translation. http://www.fi.edu/case_files/curie/le_radium.html

Usability Analysis

The overall quality of the interaction is again best determined in reviewing the range of criteria. The visual quality is somewhat lower than the British Library's presentations; still, the books appear on the screen like the originals, with graphics that show the texture and even defects. Using the magnifying glass aids the quality but makes the document more difficult to navigate. Page turning shows horizontal distortion only, in contrast to the British Library piece which is distorted in width and height. This restriction appears to increase the smoothness of page-turning. Variable lighting of the text is not available, and there are no contextual clues on how the document is stored.

Similar to the British Library's On-line Books, the interaction is very tactile and clear. Page turning is improved by limiting distortion to the horizontal dimension. Simplicity of the interaction is the key feature. User satisfaction rates high because of its simplicity and authenticity in providing the page turning experience without much distraction - just like a real book without the facilitation component.

Word searching is not available. Similarly, the ability to bookmark was not included. In fact it is the facilitation feature set that is obviously missing. The magnifying feature also works very well, authentically mimicking the functionality of a real magnifying glass on the screen. Its realism is marred only a bit by the difficulty in putting it away.

The site also requires the Shockwave plug-in, but the interaction runs equally well on major platforms. Accessibility issues are identical to those of the British Library.

Case Study: Antique Books

The Universal Library Project, based at Carnegie Mellon University, offers access to selected books from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (www.antiquebooks.net/library.html). The site also provides access to a wide variety of other ‘antique books’, but the Museum's books are most relevant to this analysis.

For example, the user can read an 1816 edition of An Introduction to the Natural History and Classification of Insects. Each page of the delicate original publication is presented individually with a next button that enables the user to proceed through the pages of the book. ‘Antique Books’ use the Thibadeau-Benoit Method (Thibadeau & Benoit, 1997) for presentation of their books. The method involves scanning (at 600 dpi), print separation, print enhancement, print storage, and non-print processing. Final presentation of the pages on-line uses a simple html interface.

The method is effective, enabling the user to interact with the original work. In another of the Museum's books, for example, the user can clearly see how the pages of the manuscript have begun to crumble. Volume 1, Issue 1 of The Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum, published in 1901, reveals the original publication of the papers associated with the discovery of Diplodocus. Readers can learn about the dinosaur's "Osteology, Taxonomy, and Probable Habits" and see the drawings of the skeletal remains.

The Thibadeau-Benoit Method is distinct because of its process of separating the text from the page. Effectively, the experience of browsing an ‘Antique Book’ is like seeing an overlay of each page's contents against a representation of the page's physical composition. This process solves the challenge of providing an appropriately sized representation of the book that is optimized for legibility; on the other hand, the on-line representation of the book is derivative rather than authentic.

Figure 3. The Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum. http://www.antiquebooks.net/library.html

Usability Analysis

‘Antique Books’ combines many key features of fidelity, interaction, and facilitation in a unique balance that is quite compelling. Applying the criteria matrix (see Table 1.) shows strength in all three areas without many technical issues.

The visual quality of pages in an Antique Book is very high. Users see a high-resolution copy of side-by-side pages that can be rotated but not animated. There are no sound or contextual cues, but virtual lighting can be controlled with a contrast button. This is a unique feature found only in this viewing system. Page turning involves simply transitioning to the next page image.

There is no sense of page turning provided. Still, the program is very easy to navigate and even allows jumping to specific page numbers. Users get a sense of having experienced the book because they see every bit of the original. Satisfaction for the average user is estimated to be high because it is immediately usable.

Image rotation and magnification are available, giving users unusual control over the images. However there are no other facilitation capabilities, such as word searching, bookmarking, or annotating.

There are a few technical issues with ‘Antique Books’. Only a Web browser is required, so it runs on all platforms; however, accessibility is a significant problem. Developers do not provide metatags.

Case Study: International Children's Digital Library

While not specifically related to Museums or archives, the International Children's Digital Library (ICDL) offers another approach to on-line representations of books (O'Leary, 2003). A project of the University of Maryland, the ICDL's mission is

to select, collect, digitize, and organize children's materials in their original languages and to create appropriate technologies for access and use by children 3-13 years old (Hutchinson, Rose, Bederson, Weeks, & Druin, 2005)

The Library's collection includes over 800 books from around the world. The user can select a book to read based upon a number of search parameters. One interesting parameter is ‘date of publication’ which ranges from the 1500s (1 book) to 2000s (354 books). The book from the 1500s – specifically, 1559 – is a Finnish primer. The front of the book is a grammar primer and the back is a religion catechism.

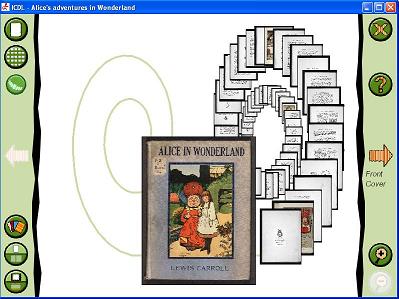

The ICDL (www.icdlbooks.org) offers four ways you can read most books: the Standard Reader, the Plus Reader, the Comic Reader, and the Spiral Reader. The Standard Reader can be used with any browser. The other readers require plug-ins. The Standard Reader presents images of the individual pages of the book and uses a simple html interface to click through the pages. The Plus Reader interface is the same as the Standard Reader, but the images are enhanced. The Comic Reader is a java-based plug-in that moves through images of the individual pages in a ’comic strip’ motion. The Spiral Reader is also a java-based plug-in. It provides a distinct interface that presents the individual pages for the user to move through in a spiral motion. If the user is unsure which Reader to use, the Help Me Choose button provides a helpful summary of each Reader's features.

ICDL books are disassembled – each book has been broken into individual pages and re-assembled on-line using one of the four interfaces described above. This technique is strategic because the ICDL invites anyone around the world to scan the pages of a children's book and send the images for inclusion in the library (Hourcade et al., 2003). The site offers detailed scanning instructions.

Fig 4: Alice in Wonderland as it appears in the International Children’s Digital Library’s Spiral Viewer. http://www.icdlbooks.org

Usability Analysis

ICDL creates a compelling way to view books designed for younger viewers. In its design may be great clues for helping children have good experiences with on-line documents. Applying the criteria matrix (see Table 1.) to ICDL (all versions), the strengths of this program are immediately clear. Visual fidelity is very high given the fact that the books are largely storybooks for children. The magnification feature allows users to see the pages magnified by a factor of 10. While there is no animation, sound, or lighting capabilities to add to the fidelity, the fidelity of these books is helped by the context provided in the "spiral" and "comic strip" versions. All pages appear on screen in order and navigation to all parts of the book is a simple click on the page.

Page turning is handled simply with forward and reverse arrows. The distortion of page contents is so smooth that users get the sense of really paging through the document. There appears to be no control over the lighting of the text or the context in which the text exists.

Commenting, word searching, and the ability to bookmark are not available. However, the ability to immediately translate the ICDL books into other languages makes it unique and very compelling for the intended audience.

Technical issues are significant with the ICDL books. The "fun" versions of the books require a plug-in for PC and Unix versions to operate correctly, but run well on all major platforms. Accessibility is a problem since there are no audio nor Web accessibility features. The simple Web-only versions also do not consistently have image metatags which would provide the visually impaired with a verbal description of the graphic.

Case Study: 3-D Book Visualizer

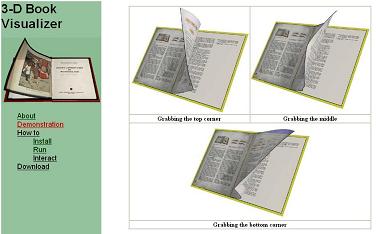

Researchers at the New Zealand Digital Library, based at the University of Walkato, have developed a three-dimensional visualization technique for books (Chu, Bainbridge, Jones, & Witten, 2004). The focus is less on the content of the book and more on the physicality of the book itself:

We do not imagine that readers will spend significant amounts of time actually reading documents in 3-D form. However they will visually handle the book, flip through the pages, sample excerpts, scan for pictures, locate interesting parts, and so on (www.nzdl.org/html/open_the_book)

The three-dimensional representations of the books are carefully detailed. The striation patterns on the page edges, the rounded edges of the spine, and the page curvatures are extremely realistic. The overall effect, however, never enables the user to experience the authenticity of interaction with the primary source. The visualization is as much like the real book as an avatar is like a real human being. The gap between the simulated and the real provides a context for the consideration of form.

Fig 5: The 3-D Book Visualizer approach differs from the other Case Studies. http://www.nzdl.org/html/open_the_book

Usability Analysis

The 3-D Book Visualizer was unique in the study. It was the only system that allowed complete 3-D manipulation of the book as an object in space. While this interaction was not to be found in other systems, it only positively affected the interaction portion of the criteria matrix. Overall fidelity was judged to be low because the book covering was drawn rather than scanned and appeared cartoon-like. Individual pages have thickness, colour, and stain variables. In other words, these elements are generated and not copied from the original. There is also no control over the lighting of the text nor the context in which the text exists.

Interaction with the 3-D Book Visualizer is quite robust and supports spinning the book in space, zooming in and out, turning one or many pages at a time, and flipping through pages. It is much better at giving the user the experience of manipulating a generic book rather than a specific text. Assuming a user's desire to interact with a specific book or manuscript, this system may not provide much satisfaction for the user. The developers openly admit that users will likely not spend much time reading documents in 3D format. However, the usefulness of the system is dependent upon the level of involvement by the user.

There is no word searching or annotation available with this system. However, it notably has bookmarks, referred to as ‘page edge markings.’ Also, comments were available in audio on most pages as well as high-resolution partial page magnification.

The 3-D Book Visualizer has several technical issues. It requires a large download and installation to operate correctly. The interaction runs on UNIX and PC platforms but not MacIntosh. Accessibility is a huge problem because the system is a stand-alone program and does not benefit from Web-based accessibility guidelines.

Summary

The criteria matrix served as a helpful tool in comparing the capabilities of various book and manuscript presentation systems. Our analysis helped to validate the tool, and we hope it will be of use to others working to provide access to documents on-line.

Each Case Study offered compelling features that would enhance the user experience, yet none matched all of the criteria collected. Cases were usually strong in one of the criteria categories indicating the underlying structure. Visual fidelity, quality of animation, and facilitation tools are distinct elements and appear in our analysis to be somewhat mutually exclusive. Pushing the quality of one higher often means reducing another. For example, higher resolution images are much harder to animate, and image data is not searchable. Perhaps the criteria matrix will inspire new projects to overcome these issues.

Accessibility

The Case Studies considered here represent a diverse group of institutions with little in common organizationally. There is no standard level of accessibility across the sites. Throughout this investigation, questions of accessibility lingered. While none of the sites considered was entirely accessible to users with disabilities, none was extraordinarily inaccessible either.

Museums struggle continually with issues of on-line accessibility. In the United States, museums that receive federal funding are bound by Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act (Access Board, 2000, Tuohy, et al, 2004). For museums that are not bound by Section 508, the Access Board guidelines still provide a useful metric. The unfortunate reality, however, is that full compliance with Section 508 requires multiple iterations of site design: this is both expensive and counterproductive to the development of inherently visual original representations of books. The Case Studies are a testimony to the nature of the compromise between accessibility and authentic representation.

What's Next? Go Ask Alice.

Users can interact with the original text of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland using the 3D Book Visualizer, or they can visit to The British Library and turn the pages of Carroll's original manuscript. The International Children's Digital Library has two copies of the book - English editions from 1905 and 1916 - on its shelf. Perhaps it is fitting that this book is so often represented. Like Alice, museums and libraries have stumbled into a wonderland where the possibilities for the presentation of their collections are limited only by imagination.

References

Access Board (2000). Guide to the Section 508 Standards. Retrieved January 2006 from http://section508.gov/

Chu, Y.C., D. Bainbridge, M. Jones, & I.H. Witten (2004). Realistic books: a bizarre homage to an obsolete medium? Paper presented at the 4th ACM/IEEE-CS joint conference on Digital libraries.

Dutton, G. (1998). Turning electronic pages. Popular Science, 253(2), 33.

Hourcade, J. P., B. Bederson, A. Druin, A. Rose, A. Farber, & Y. Takayama (2003). The International Children's Digital Library: Viewing digital books on-line. Interacting with Computers, 15, 151-167.

Hutchinson, H. B., A. Rose, B. Bederson, A.C. Weeks, & A. Druin (2005). The International Children's Digital Library: A case study in designing for a multi-lingual, multi-cultural, multi-generational audience. Information Technology and Libraries, 24(1), 4-12.

Krug, S. (2000). Don't Make Me Think: A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability. New Riders Press

National Cancer Institute. (n.d.) Research-Based Web Design Guidelines. Retrieved January 2006 from: http://usability.gov/guidelines/index.html

Nielsen, J. (1999). Designing Web Usability. New Riders Press

O'Leary, M. (2003). The many meanings of ICDL. Information Today, 20(9), 41.

Ojala, M. (2003). Turning the pages of priceless manuscripts. EContent, 26(8/9), 8-9.

Shigo, K. (2003). British Library unveils Electronic Delivery service, new 'Turning the Pages' technology. Computers in Libraries, 23(8), 8.

Thibadeau, R., & E. Benoit (1997). Antique Books. D-Lib Magazine.

Tuohy, P., H. Garton, J. Beeler, & J. Slatin (2004). For All the World to Share: Developing and Implementing Accessible Web Sites. Retrieved January 2006 from: http://www.archimuse.com/mw2004/papers/tuohy/tuohy.html

Cite as:

Elinich K., Page Turning: Revealing The Interface Issues Of On-Line Document Viewing, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2006 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/elinich/elinich.html