Juan Leon and Matthew Fisher, Night Kitchen Interactive, USA

Abstract

Virtual characters developed in rich-media play increasingly valuable and conspicuous roles in educational games and courseware, but they can be detrimental to the instructional value of these materials when used inappropriately. The guidelines presented here draw upon learning theory, cognitive psychology, studies in human-computer interaction, and narrative theory to provide a framework for placing virtual characters in the optimal ‘teachable moments’. Our work with the National Constitution Center in the development of the on-line interactive exhibit Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads serves as the case study in light of which we have developed these guidelines. We focus on the human-like value of a virtual mentor in courses modeled on ‘cognitive apprenticeship’, describing the three principal roles played by the mentor. We then explore the social psychology behind the high engagement these characters offer, the instructional events an educational game must provide, and the structure of a typical story line. We describe the elements – including interactivity – that must be added to stories to make them more fully educational and identify the parts of a story in which the characters can best present facts, concepts, processes, procedures, or principles. We conclude by noting ways in which today’s understanding of narrative comprehension demands careful attention to graphic illustration in stories and by presenting the reader with a straightforward process for aligning story genre, story events, and virtual character placement with the educator’s learning objectives.

Keywords: digital storytelling, interactive exhibit, educational game, virtual character, rich-media, instructional design, cognitive apprenticeship, cognitive psychology

Introduction

The educational potential of digital storytelling continues to attract the enthusiastic attention of museums, teachers, and commercial software companies even as the instructional merits of such stories come under increasing scrutiny. Today, it is not unusual to hear professional educators and trainers refer with a certain condescension to ‘edutainment,’ and we frequently read disconcerting headlines about how the multimedia bells and whistles in a piece of educational courseware have distracted learners from actually learning. Consider this example of sobering news recently appearing in Sydney, Australia:

research published in the journal Education 3 to 13 has found that pupils who use interactive programs cannot remember stories they have just read because they are distracted by cartoons and sound effects (Henry and Jones 2006).

Despite these kinds of failed interactive materials, the widely documented successes of digital storytelling projects demonstrate that storytelling involving museum objects can be remarkably powerful for both story developers and their audiences. Considering one such success, the digital storytelling project reported by Julie Springer at the National Gallery of Art, we realize that one of the keys to success seems to be the following: adopting new communications technologies while continuing to develop materials in line with well established educational principles and proven teaching methodologies. In the case of the National Gallery project, this attention to sound educational practice included having teachers write their lessons in the personas of historical characters who function as guides to events and scientific discoveries: “Details of the guide’s life and experience become the bridge for connecting to formal student learning goals” (Springer, Kajder et al. 2004). Our own work with the National Constitution Center’s Lincoln exhibit has allowed us to add to the growing wealth of understanding about how characters in digital stories can both engage learners and deliver on the learning outcomes.

Virtual Characters Offer More than Edutainment

Today’s rich-media interactive design tools allow animated characters to be created relatively quickly and inexpensively. Better Web browsers, faster processors, and expanded bandwidths allow these characters rich with audio and visual detail to play over the Internet. These characters are engaging and highly adaptable – natural components of educational presentations. They combine the instructional value of graphics – sensory stimulation and visual representation – with the appeal of human social interaction. Audiences tend to engage with these characters as if they were real people.

However, animated characters can also detract from the instructional value of the programs in which they are used. The characters may draw our attention in the wrong directions, convey irrelevant information, or target no learning objectives at all. The guidelines we have evolved for making optimal use of virtual characters (virtual characters) in educational, rich-media presentations are designed to help courseware designers avoid these pitfalls.

We’re Presenting Design Guidelines, Not Rules

We refer to our prescriptions only as ‘guidelines’ for two reasons: 1) research into the optimal use of these characters is still immature, and 2) we understand that developers of these characters are pursuing a sophisticated craft. For the foreseeable future, their work will be as much intuition-based as it may be theory-based.

Our guidelines draw upon learning theory, cognitive psychology, and studies in human-computer interaction to create a framework for designing effective characters and placing them into the most suitable story structures. Our focus is on the instructional role of these characters and their optimal placement in the narratives they frequently inhabit. The most opportune intersections of learning objectives, virtual character types, and narrative elements we will refer to as ‘teachable moments,’ the moments that are most likely those of maximum pedagogical opportunity.

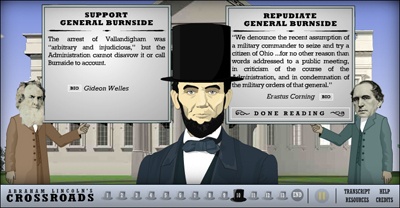

Fig 1: Teachable Moments

Let’s Begin With An Interactive Exhibit About An Historic Decision Maker

Our recent project with the National Constitution Center (NCC), Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads, serves as the primary case study for this discussion (http://www.constitutioncenter.org/lincoln). The on-line interactive exhibit was created to complement the NCC’s first travelling exhibition, Lincoln: The Constitution & the Civil War, which debuted at the NCC in June 2005. Within our framework the Lincoln story is treated as an historic epic – the epic’s many episodes serving as opportunities to dramatize decision points in Lincoln’s political career.

Fig 2: Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads introduction. Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads http://www.constitutioncenter.org/lincoln

This epic tale is presented in thirteen ‘chapters’, within which decision points are dramatized in the interaction of an animated Lincoln with representations of historic counsellors. These counsellors include well-known advisors such as William Seward and lesser known but influential figures such as Joshua Speed.

The exhibit’s instructional aims were four-fold:

- to convey new facts about Lincoln’s times and the conditions under which he made decisions

- to improve the audience’s understanding of decision-making processes

- to dramatize the significance of human choice in shaping the course of the future

- to nurture a greater personal identification between students and the mythic President.

The on-line story format, with its animated Lincoln, was designed to achieve these aims by improving retention of facts and concepts, authentically engaging learners in a decision-making process, simulating participation in deliberations that influenced the course of history, and encouraging a personal, subjective understanding of an historical icon.

Lincoln The Mentor: Providing For A Virtual ‘Cognitive Apprenticeship’

To achieve these educational objectives, we partnered with Steve Frank and others at the National Constitution Center to create a virtual Lincoln that could provide learners with a ‘cognitive apprenticeship.’ Cognitive apprenticeships resemble traditional apprenticeships. Rather than focus on trade skills and bodily-kinesthetic training, however, these apprenticeships use mentors to model cognitive processes such as problem solving. Much like traditional apprenticeships, cognitive apprenticeships allow learners to develop their skills through authentic domain activities. Medical students can better learn the reasoning strategies employed by practising clinicians, for example, when challenged to design a new instrument for a testing laboratory under the guidance of experts (Newstetter 2005). Instructional designers can learn performance systems analysis by working with mentors on corporate consulting projects (Darabi 2005).

The first step in designing such an apprenticeship is to identify specific mental processes and find ways to externalize them – make them tangible to students. With our focus in Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads on major decision points in the President’s political career, we externalized Lincoln’s decision-making processes by having him both voice his thoughts and interact with counsellors who voice differing opinions. As our learners explore the exhibit, they are exposed to all the four types of content that have come to be characteristic of cognitive apprenticeships (Kovalchick and Dawson 2004):

- Learners are presented with facts, concepts, and procedural knowledge by Lincoln and his peers.

- This content is integrated with the problem-solving strategies modeled by Lincoln, the mentor.

- Learners are exposed to metacognitive strategies such as Lincoln’s planning and evaluating.

- Learners monitor their own learning as they reply to Lincoln’s queries and hear his feedback.

Much of the existing research on cognitive apprenticeships confirms the model’s effectiveness when human mentors are involved. How successfully can students be apprenticed to virtual characters, non-humans such as our virtual Lincoln? So far, results have been impressive across a variety of disciplines. For example, recent research into an on-line course offered to German dermatology students since 1999 documents that the model of a cognitive apprenticeship adopted for the course has consistently resulted in better knowledge retention and better success in applying knowledge to diagnoses (Roesch, Gruber et al. 2003). The key characters in this on-line course are virtual patients and virtual mentoring physicians.

Evaluation

The overall outcomes of our own approach are documented in research being conducted with a group of history classes in a local Pennsylvania high school. In collaboration with Beth Twiss-Garrity, Director of the Museum Communication program at The University of the Arts, and Merritt Haines of that program, we have partnered with four 11th grade U.S. history classes (two academic level and two advanced placement) to evaluate the impact of our virtual mentor. We are testing classes for retention of facts, a more sophisticated understanding of decision-making, and an expanded appreciation of Lincoln both as a person and political leader. We also targeted specific items in the Academic Standards for History specified by the Pennsylvania Department of Education (2002):

- analyzing and explaining the fundamentals of historical interpretation with regard to multiple points of view

- associating causes with results

- understanding the context for events.

Methodology

In February 2006, “Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads” was evaluated by fifty-three 11th graders at a suburban Philadelphia middle-class high school. Half (N=28) of the students were enrolled in an AP level history course that had studied the Civil War in December 2005. The other half of the students (N=25) were in the Basic level of Social Studies and had not studied the Civil War since 8th grade. Likewise, half of the students in the whole sample used the rich media version (N=28) and half used the low broadband version (N=25). One Basic class used both, though only did the survey for the HTML version.

All students followed the same protocol. They took a pre- and post-test with Survey Monkey. In between tests, they had time to explore the on-line exhibit on their own and through directed discovery. The surveys included multiple choice questions and Likert scale statements as well as two open-ended questions on the post-test. Following the total survey period of about a half hour, a class discussion was held covering the main points.

The survey attempted to answer five main questions relating to cognitive and affective learning:

- Did students gain any new knowledge about the Civil War and Lincoln?

- Were psycho-social characteristics at play in the learning, due to the use of an animated Lincoln version?

- What was the role of narrative in learning?

- Could students see that history is not pre-ordained but results from a series of decisions made by real people in the past?

- Did the use of multiple points of view and an ability to make choices themselves help students understand the content?

Results were tabulated to determine change between the pre- and post-test answers. In addition, data was studied to see if there were differences between the AP and Basic students, and between those using the rich media versus HTML versions.

Preliminary Results

Preliminary analysis of the survey results shows that the use of an on-line exhibit can make learning more enjoyable for high school students of all academic levels, especially when students have a chance to make decisions based upon a variety of points-of-view. While it does not necessarily increase their cognitive learning of facts, it vastly improves their understanding of historical process and interpretation. Students learn that history is not pre-ordained, but that real people in the past weighed various points-of-view and facts to make a decision that had lasting consequences. Students also generally see the use of an animated character and rich media as positive. It not only makes the learning more fun, but it also enhances affective learning and has a small positive influence on cognitive learning. Due to their media-saturated short attention spans, students request even more interactivity and animation to enliven the study of history. (Twiss-Garrity and Haine 2006; further evaluation results are available at http://www.whatscookin.com/lincolnresearch/.

Mentors Play Many Roles — So Does a Virtual Lincoln

In order to fulfil the responsibilities of a mentor, our virtual Lincoln must play many variations on his role. In so doing, we found that he fell into patterns of virtual character behaviour we’ve previously identified as common across a wide range of learning environments. In early 2005 our review of educational and informational presentations in both for-profit and not-for-profit environments identified three common roles for virtual characters: they can serve as guides, models of behaviour, or interactive agents.

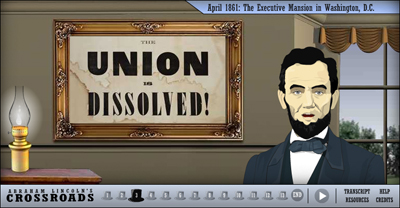

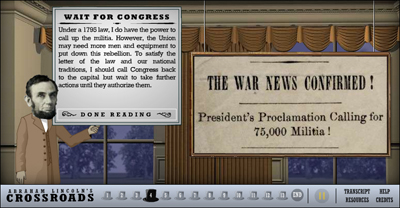

First, in the role of guides virtual characters function much like docents, masters of ceremonies, or tour conductors. Lincoln functions as a guide when he explains the nature of the interaction to learners as soon as they’ve arrived at the home page. He also functions as a guide when he sets up each of his thirteen decision-making episodes.

Fig 3: Lincoln Explains Historical Context of an Impending Decision. Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads http://www.constitutioncenter.org/lincoln

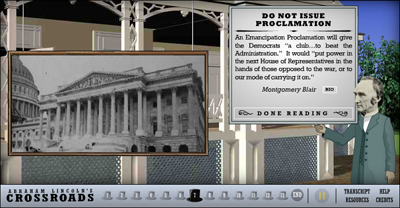

Secondly, as models of behaviour virtual characters can demonstrate physical movements, social interactions, or individual behaviours. Ours being a cognitive apprenticeship, Lincoln does not demonstrate how to wear a stovepipe or stuff it with notes and correspondence (as the historical President is said to have done). Instead, he externalizes his decision-making in the form of advice heard either from contemporaneous counsellors or from personifications of himself.

Fig 4: Lincoln Hears from Advisor. Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads http://www.constitutioncenter.org/lincoln

Fig 5: Lincoln’s Internal Debate is Externalized in Form of Presidential Alter Ego. Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads http://www.constitutioncenter.org/lincoln

Thirdly, when operating in the mode of interactive agent, characters directly address and query the audience of learners, responding in turn to the audience’s feedback. Lincoln adopts this role in each one of our decision-making episodes, turning to the audience to hear its opinion on which of the opinions aired he should most take to heart. After the learner has made a choice, Lincoln provides feedback.

Fig 6: Lincoln Invites Learner to Make Historic Decision Along with Him. Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads http://www.constitutioncenter.org/lincoln

Finally, is not uncommon for virtual characters to combine these three roles in various ways – sometimes moving among them in rapid succession. Our Lincoln functions as a guide when he introduces the on-line exhibit and its episodes; he is a model of decision-making in the middle of each; and he interacts with the learner in posing and responding to “What would you do in this situation?” challenges at the end of each.

Virtual Characters Engage and Instruct

Our experience and the emerging research suggests that in an on-line educational environment, virtual characters can stand in for their human counterparts in useful ways. How fully can they do so? The work of Reeves and Nass appears to demonstrate that rich-media virtual characters will be responded to almost exactly as if they were actual human social actors (Reeves and Nass 1996). That is to say, interactions with media-generated characters are in almost every significant way just like interactions with actual people: “There are few discounts for media, few special ways of thinking or feeling that are unique to media, and there is no switch in the brain that is activated when media are present” (Reeves and Nass 1996, 251). Audiences will engage in polite exchanges with virtual characters, believe them (or not) much as they would a real human being, and respond to their appearance and presentation much as they would to that of a person in an actual social environment. We will flatter virtual characters, have our senses aroused by them, and be predisposed to give greater credence to words placed in the mouths of virtual experts – such as Presidents. It’s due to these strong social responses, Reeves and Nass demonstrate, that the use of virtual characters will, in general, strengthen the attention, emotional impact, and memorability of material.

Of course, the use of virtual characters alone is not any guarantee of their instructional effectiveness for a given instructional purpose. As educators and course designers, we must be especially careful to define and clearly present just what it is that will be closely attended to, strongly felt, and well remembered. In the case of our Lincoln project, a virtual cognitive apprenticeship well served the purpose of teaching students about Presidential decision-making and related issues. Now, we’ll try to draw up more general guidelines for developing instructional stories that make use of virtual characters. We’ll consider story structure and take into account typical audiences – their psychology and their expectations.

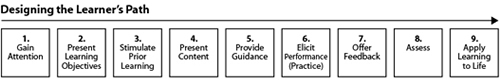

‘Events Of Instruction’ vs. The Typical Story Line

Many of the principles of effective lesson design are well known, though the details of their application in rich-media environments continue to be worked out. Well-designed instructional materials are carefully targeted and complement our natural learning processes in several ways: Carefully targeted materials address specific domains of learning – psycho-motor (such as physical skills), affective (such as attitudes), or cognitive. They then facilitate a learner’s progress through the stages of learning by providing for what Robert Gagne called the “events of instruction” – attention gaining, objective setting, invoking of prior learning, presenting new material, creating scaffolding, providing practice, offering feedback, conducting assessment, promoting retention and transferring new knowledge to real-life situations (Kruse 2006).

Fig 7: Gagne’s Nine ‘Events of Instruction’ (adapted)

Along with these guidelines for identifying the domains of learning and the essential events of instruction, we have evolved a set of best practices that pertain specifically to addressing the cognitive domain. For the purposes of instruction, the cognitive domain can be divided into five sub-categories, depending on the kind of information at issue (Clark 1999):

- Facts

- Concepts

- Processes

- Procedures

- Principles

From an educational perspective, then, our task has been to develop a framework for designing courseware or rich-media presentations that make the most appropriate use of virtual characters in light of these received guidelines. Because virtual characters typically appear in stories, and because stories have inherent appeal and instructional potential, we will consider how the structures of instructional stories can best complement the educational purposes of virtual characters.

Typically, Story Lines Don’t Include Educational Apparatus

Story structure can add appeal to educational materials, but stories and their events can also draw attention away from learning objectives or teach the wrong things. Let’s take the story line of a popular movie, for example. Through Jaws we learn much that is fairly accurate about the anatomy of the white shark and much that is entirely wrong about shark behaviour. We would not charge the producers of Jaws with negligence because the movie is an exercise in thrills and entertainment, not education. The same deficiencies the Jaws story has from an educational perspective, however, carry over into stories of all kinds. When we reflect on Gagne’s ‘events of instruction’ listed above, we notice that stories are likely to capture some of the key events but not others. Stories are likely to attract the attention of audiences, present goals or challenges, and invoke prior knowledge. They are likely to present new material and may provide some scaffolding. They won’t, however, provide practice opportunities to the audience, explicitly assess their knowledge, or offer feedback.

Fig 8: Instructional Elements Missing from Typical Story Line

Instructional Stories Can Use Virtual Characters in Special Ways

The Lincoln interactive exhibit overcomes the structural incompatibility between story and lesson in two ways. First, we align the protagonist’s goals – Lincoln’s wanting to make the best possible decisions – with those of the learner – the student learning about good decision-making. That is, the audience’s relationship to the President is one of apprentice to master. Secondly, we have Lincoln not only model behaviour but also address each learner. In the role of interactive agent, the virtual President functions as a tutor who provides opportunities for practice, supplying advice and encouragement based on each user’s responses. These two essential elements of our model are indispensable to the cognitive apprenticeships we have already discussed, of course. They can also be cast into more general guidelines:

- Let the goals of the protagonist in an instructional story mirror or parallel those of the learner.

- Let the protagonist – or another character in the story – play the indispensable role of interactive virtual tutor.

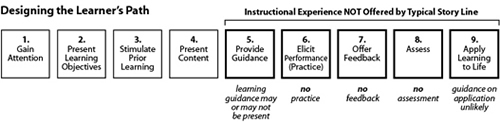

All Stories Manifest An Essential Line Of Development: Beginning, Middle, End

While we must take care in designing educational stories so that essential events of instruction don’t go missing in them, we can also benefit from traditional story structures and the expectations readers and audiences have based upon them. All stories conform to an inherent line of development, and the three major sections of this line each lend themselves to different kinds of instructional goals and presentations. All stories begin with an event that sets a protagonist in motion. The protagonist may discover a lack, or dream of obtaining a benefit. Hamlet is told by a ghostly visitor that his claim to the throne has been usurped. In Jack and the Beanstalk, Jack’s home is without food, so he sets off to sell the cow. During the middle part of a story – typically the longest part – the protagonist acts and learns from the consequences of those actions. The protagonist attempts to overcome obstacles in the effort to achieve goals. Ulysses learns something new on each of the dangerous islands he must visit as he makes his way home to Ithaca. Ripley learns more ways to dispose of aliens in the film Aliens. At the story’s end the central problem or opportunity is either won or lost. The protagonist’s efforts have resulted in either desirable or undesirable outcomes. Goldilocks learns “Don’t nap in bear houses.” James Bond learns the full extent of a villainous plan, obligingly narrated by a gloating villain, and then foils it.

Each Story Segment Offers Teachable Moments

While instructional opportunities can find their way into any part of any story – story structures are flexible, complicated, and often recursive – we are suggesting that the fundamental story structure just outlined will predispose a story to accommodate certain kinds of messages during certain stages. We call these opportune moments ‘teachable moments.’

Facts and concepts can be most naturally presented at a story’s beginning, when background information is expected. This is also an opportune place to introduce virtual characters that will function as primary guides. A guide’s expository role is most suited to this stage of story development. The ghost of Hamlet’s father makes a long recounting of foul play while we listen patiently. Jack’s impoverished household is described.

Processes and procedures are best presented in the story’s middle – how to evade a Cyclops or how to use the void of space as a powerful vacuum cleaner for hard-to-stop aliens. There, a variety of efforts and outcomes can be experienced in sequence. It is also during this middle stage that the greatest amount of time passes. Accordingly, processes and procedures can be allowed to play themselves out. virtual characters that will function as models play their most elaborated roles in this stage. The middle is also the place for interactive agents to pose practice problems, present interim assessment challenges, and offer feedback.

Principles are best driven home at the story’s conclusion – the traditional location of ‘the moral.’ With the story’s conclusion, major themes/patterns of a story’s line of development have been completed and the lessons learned. Here, interactive agents may summarize learning, present summative assessments, and guide the learner to recognition of principles. This guidance often involves work of synthesis or evaluation. In our interactive exhibit, Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads, the virtual President appears after all episodes have been explored to tell the player how often the two of them agreed on decisions. Learners are encouraged to re-evaluate – though not necessarily change – their judgments, and Web links are provided for further study and investigation of each of the episodes dramatized by the exhibit.

Fig 9: Teachable Moments Align Story Segment and Learning Objective

Many culturally familiar story types include variations built upon this fundamental pattern and should be considered when matching a story form to learning objectives of various kinds. In the interactive exhibit Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads we have turned an historic epic into an apprentice’s tale because of the nature of our resources and our affinity for the instructional approach of ‘cognitive apprenticeship.’ The fact that the Lincoln story is well known and the character already highly developed in popular consciousness allowed us to dwell ‘in the middle’ of that story, presenting decision-making processes and procedures to the audience as the contexts for those decisions changed.

Narrative Understanding is Fundamental but Incomplete

Why do stories have the strong instructional potential that they do? Stories are among the oldest tools of instruction available to humankind, and story-based understanding appears to be fundamental to human understanding of both society and the natural world (Turner 1996).

Recent research also suggests that our brains are wired to take stories seriously in everyday thinking. The work of Richard Gerrig and other cognitive psychologists seems to indicate that the cognitive processes used to comprehend fictional stories are no different from those used to comprehend the actual day-to-day world (Gerrig 1993). We use our knowledge of reality to make the inferences and imaginative constructs that bring fictional stories to life, and stories, in turn, recast the ways in which we perceive reality. Thus, a mechanical shark placed in the appropriate story line – that of the Jaws movie – can serve to keep previously unconcerned beachgoers far away from the shore for years. What is more, users will feel suspense about stories they’ve become involved with even if they know the outcomes. For most viewers, the Jaws movie is suspenseful even after repeated screenings. This is a common phenomenon that Gerrig has labelled ‘anomalous suspense.’ Fictional stories have real-world impact, and they can remain engaging even when outcomes are known. These are important confirmations of our shared sense that stories can teach and that familiar stories, such as the Lincoln historic epic, can be engaging vehicles despite their familiarity.

The ‘Minimalist Hypothesis’: Why We Need Instructional Graphics

Another telling aspect of the Jaws phenomenon was the knowledge of white shark anatomy with which moviegoers left theatres. The remarkably life-like robot impressed the distinctive white shark profile on the mind of audiences around the world, and many members of those audiences proceeded to libraries and bookstores to learn more about the real-life monsters of the deep. Would the movie have been as suspenseful without the realistic robot? Most likely, yes. Early attack scenes show little of the shark and yet are as powerful as the later scenes. Without the mechanical shark, though, audiences would have left with no new knowledge of white shark anatomy. This is an important point for visual designers, and it speaks to what Gerrig labels the ‘minimalist hypothesis’: audiences such as readers will visualize little of a story beyond the minimum need for local coherence – understanding of what is happening at the moment. What educators need learners to see, educators must be sure to show.

The ‘Principle Of Least Departure’: Why We Need Contextual Illustrations

When audiences do feel compelled to fill in the gaps of a representation, Gerrig demonstrates that audiences tend to be governed by the ‘principle of least departure’: unspecified elements of a narrative are modeled as closely as possible on the world already known to the audience member. Think of George Méliès’ early silent film Trip to the Moon – or the unnecessarily banked turns of space ships in Star Wars films. Consequently, instructional graphics must serve at least two important corrective purposes:

- Illustrate what would otherwise only be minimally visualized by an audience.

- Fill the imaginative space that could otherwise be populated by inaccurate images.

We are saying, then, that virtual characters appropriately placed in stories promise powerful educational benefits because the virtual characters prompt learner attention, sensory arousal, and retention of learning. The story environments themselves should be illustrated so as to compensate for the visual ‘minimalism’ of the story comprehension process and the cognitive conservatism reflected in the principle of least departure.

Fig 10: Le Voyage dans la Lune / A Trip to the Moon (Georges Méliès, France, 1902)

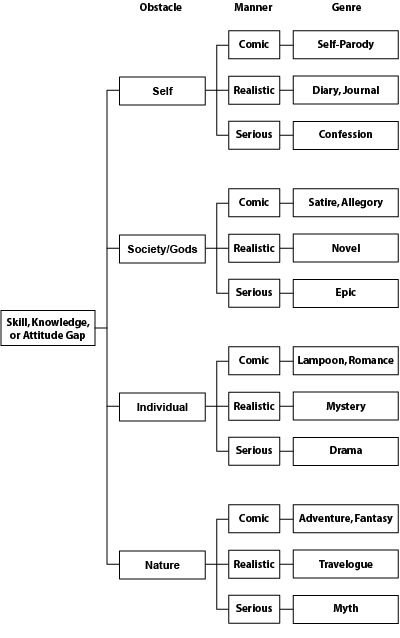

Match Learning Objective to Obstacle; Obstacle & Manner to Genre

The teachable moments we have described are rather abstract. They are characterized by story segments, sub-elements of learning domains, and the roles virtual characters can play. Actual stories involve settings (in particular times and places), characters (with personalities), and so on. We feel that, from the instructional perspective, it is most helpful to think through learning objectives and match them to story elements at this abstract level. What of the other necessary details? How do you decide whether your teachable moments will be presented in a romantic comedy, a tragedy, or an historical farce?

Designers of interactive educational games and stories have gravitated towards a set of practices. The episodic nature of quests and adventures, for example, make them popular narrative vehicles for many kinds of instruction. The framing story can be established once and then instructional objectives can be addressed through a long – potentially unlimited – middle. Adding simulations can make them well suited to teaching psycho-motor skills. Briefer mysteries can emphasize specific problem-solving skills. Education targeting the affective domain can make use of first-person, introspective genres such as autobiography, diary, or the epistolary novel. We can use the framework presented in this paper, however, to push far beyond this increasingly clichéd vehicle while continuing to add instructional value to our designs.

We’ll wrap up our discussion, then, with a recipe for a fresh beginning: First, map your learning objectives to the obstacles your virtual characters will encounter in your story, the obstacles encountered and overcome in the story’s middle as characters pursue goals. Then, consider whether these obstacles have primarily to do with the principal character(s) in conflict with:

- Self

- Society

- Nature

- Another individual

Finally, consider the mood of the story you have in mind. Will it be comic or fanciful? Will it be realistic instead? Or will it be gravely serious? Establishing the type of principal conflict and the perspective from which the protagonist’s trials will be presented will point you in the direction of distinct story type – the story genre. Deciding on whether you’ll want your character to have a positive or negative outcome will direct you toward variations on these genres, as will determining the most useful setting in time and place. Thus, a mystery could be solved or remain unsolved. It could be set in the past, present, or future of a remote or nearby location.

Fig 11: Examples of Story Genres Mapped to Obstacles via Manner

Conclusions

In exploring the use of today’s increasingly popular virtual characters, we’ve considered the three roles they typically play in presentations. We’ve noted that these characters – whether in the role of guide, model, or interactive agent – attract audiences, stimulate them, and offer a more memorable experience than the same learning content experienced without the characters. This is due in large part to our natural social response to virtual characters. We’ve also cautioned that these benefits can turn presentations into ‘edutainment’ that misses or ignores worthwhile learning objectives. Placing virtual characters into stories furthers the character’s instructional value, but does nothing in itself to guarantee learning outcomes. Still, we seek to take full advantage of the instructional power of stories.

The act of interpreting stories draws upon our conscious and unconscious knowledge of the world even as it recasts our perception of that world. To make best use of this powerful vehicle we must be especially careful to illustrate all important information – including contextual details that may otherwise be incorrectly imagined by audiences. Stories only become explicitly instructional, however, when they include guided practice, feedback, and assessment. Into such instructional stories, characters can be strategically placed so as to maximize their effectiveness. The beginning, middle, and end of a story each offer distinct ‘teachable moments’ that should be taken advantage of.

We should strive to use carefully-cast virtual characters concentrating presentation of facts and concepts at the beginning (with guides), processes and procedures in the middle (with models of behaviour and with interactive agents), and principles toward the end (with interactive agents). By carefully aligning our learning objectives with the obstacles created to challenge our characters during a story’s middle, we help ensure attainment of the desired learning outcomes. By drawing upon our vast cultural repertoire of story variations we can populate our stories with the most compelling characters – present-day or historical – and illustrate the stories with the most relevant visual details.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Steve Frank, Brian Riggs and Matthew Pinsker for their project direction and script development on the Abraham Lincoln's Crossroads interactive exhibit. We would also like to thank Beth Twiss-Garrity and Merritt Haines for their collaboration in developing the associated research component.

References

Clark, R. C. (1999). Developing Technical Training: A Structured Approach for Developing Classroom and Computer-based Instructional Materials. Silver Spring, MD, International Society for Performance Improvement.

Darabi, A. A. (2005). “Application of Cognitive Apprenticeship Model to a Graduate Course in Performance Systems Analysis: A Case Study.” Educational Technology, Research and Development 53(1): 49.

Gerrig, R. J. (1993). Experiencing narrative worlds : on the psychological activities of reading. New Haven, Yale University Press.

Henry, J. and B. Jones (2006). Interactive learning fails reading test. Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney.

Kovalchick, A. and K. Dawson, Eds. (2004). Educational Technology: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California, ABC CLIO.

Kruse, K. (2006) “Gagne's Nine Events of Instruction: An Introduction.” Available: http://www.e-learningguru.com/articles/art3_3.htm

Pennsylvania Department of Education, (2002). Academic Standards for History. 22 PA. Code, Chapter 4, Appendix C. Pennsylvania Department of Education. #006-275..

Reeves, B. and C. I. Nass (1996). The media equation : how people treat computers, television, and new media like real people and places. Stanford, Calif., CSLI Publications ; Cambridge University Press.

Roesch, A., H. Gruber, et al. (2003). “Computer assisted learning in medicine: a long-term evaluation of the 'Practical Training Programme Dermatology 2000'.” Medical Informatics & the Internet in Medicine 28(3): 13p.

Springer, J., S. Kajder, et al. (2004). Digital Storytelling at the National Gallery of Art. In D. Bearman and J. Trant (eds.). Museums and the Web 2004: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, 2004. last updated March 25, 2004. Available: http://www.archimuse.com/mw2004/papers/springer/springer.html

Turner, M. (1996). The literary mind. New York, Oxford University Press.

Twiss-Garrity, B.A. and M. Merritt Haine (2006) Abraham Lincoln’s Crossroads”: On-line Exhibit Evaluation, Preliminary report: February 20, 2006. Available from http://www.whatscookin.com/lincolnresearch/

Cite as:

Leon, J., and Fisher M., The Use of Virtual Characters to Generate Teachable Moments, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2006 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/leon/leon.html