Alan Lishness, Gulf of Maine Research Institute and Dana Hutchins, XhibitNet, USA

Abstract

This paper describes the collaborative, user-centered design process used to develop the Gulf of Maine Research Institute's (GMRI) new on-site and on-line marine science education center. At GMRI, 5th and 6th grade students conduct their own in-depth, simulated marine research investigations, including handling and observing both live and dead specimens. Investigations are facilitated through networked, interactive computer research stations with digital video dissecting microscopes, video notebook report cameras and aquarium schooling tank cameras. Teams of students make virtual trips into the Gulf of Maine to record scientific data using actual echogram images, and to conduct commercial fishing expeditions based upon a realistic economic simulation. Students record their observations with their digital tools and present their findings in summary ‘peer review’ sessions. All of the students' hypotheses, evidence and findings are saved to individual personal science notebook Web sites which they and their teachers and parents can access at school or home. On their personal sites, students can annotate, update and export all of their digital movies and images to create additional extended research reports.

Keywords: interaction design, user interface, personalization, content management system

Introduction

"Consuming culture is never as rewarding as producing it."

Mihalyi Czikszentmihalyi, Creativity (1996)

Until 2005, the Gulf of Maine Research Institute (GMRI) was more a virtual organization than a bricks and mortar facility. A major element of the institution was its Internet presence; GMRI began utilizing the Web for educational outreach in mid-1994. Thanks to the popularity and number of inbound links to our content sites, we have consistently been in the top five results on Google for the words ‘satellites’ and ‘lobsters’ since Google began in 1998. In 1997, GMRI began the Vital Signs program putting Apple eMates and then PDAs to work by students as data collection and analysis tools. In 2001 the Vital Signs PDA tools were linked-in to a Web database and GIS user interface. More than sixteen thousand students around Maine have been involved in that program, and an equal number are now using the same tools and a localized GIS interface in a cross-border project in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

For more than thirty years a primary development goal of the organization has been to build a major cold-water aquarium in Portland, Maine. In 2000 the organization refocused its efforts on building a marine research laboratory based upon a unique model.

Since colonial times, a large portion of Maine’s economy has been based upon its abundant fisheries. Unfortunately, in recent years once-abundant fish stocks have declined, and efforts to understand and manage those stocks have become contentious and politically charged. GMRI leadership identified a need for an entity to serve, not as an environmental and conservation advocate, but as a neutral convener of commercial fishing interests, researchers and policy-makers, as well as an educational resource. In 1998, the organization pioneered the practice of collaborative fisheries research, bringing fishermen and scientists together to conduct research using commercial fishing vessels and their crews as hired research platforms in the Gulf of Maine. Over the past eight years the project has proved highly successful. GMRI’s collaborative research approach has expanded and then been adopted in fisheries along the west coast of the US from southern California to Alaska and to fisheries in the North Sea off the coast of Ireland with similar success.

In 2001, the success of these education, research and community-building efforts became the foundation for the design and development of a new public outreach effort; an educational facility to translate and communicate Gulf of Maine fisheries research and ecosystem science to the people of Maine. An early step was to form an advisory working group of marine educators, classroom teachers, scientists, Web strategists, aquarium exhibit and user-experience designers and technologists.

A major premise of the project was that the Internet, and interactive technology in general, would play a significant role in the learning experience. At the same time, GMRI staff had learned well that technology alone, or for its own sake, would not connect visitors directly to the living organisms and the ecosystem science of the Gulf of Maine. Making that direct, personal connection would require living, moving organisms (as well as some formerly living samples) that could be seen up close, handled, inspected and even smelled. This guiding principle became embodied in a catchphrase often heard during the project; “It’s the fish, stupid.”

By early 2002 the working group had formulated a vision, audience definition, project values, themes and strategies, as well as a mission for the group itself.

Project Vision: To create a compelling and enriching sensory experience that illuminates cutting-edge research while immersing visitors in the unique character of the Gulf of Maine.

Working Group Mission: To define the infrastructure required to develop and maintain the content which portrays the science occurring at the lab and elsewhere. End product must be a complex adaptive system to ensure sustainability and evolution.

Audience Definition: Middle School students who will visit the public interface during school hours. Professional educators on the advisory group recommend that 5th grade students may prove a more attentive and engageable audience than 6th grade students.

Values, Strategies, Themes, And Presentation Opportunities As Guides And Background To Exhibit Systems Development.

1) Overriding Premise

The overriding premise is that each visitor is recognized as an individual, and that, to the greatest extent possible, the visitor experience is customized. Examples include the presenter memorizing the name of each student, and equipping each student with a Palm-like device that gathers custom visitor input and provides post-visit resources. Building/exhibit technologies will also recognize the presence of visitors.

2) Social aspects

Social aspects are essential to the GML public space experience (e.g. opportunities to share saved products of interaction and observation with other students, parents, teachers, etc., both temporarily and long term for access on the Web)

3) Takeaways

Both tangible and virtual artifacts of the experience (takeaway visitor ‘badges’, on-line mementos such as custom, personalized Web pages/’objects’, collections, notes, etc.) extend, amplify the impact of the experience

Iteratively developing and testing exhibit and Web site prototypes with target groups will be essential to creating effective visitor experiences

4) Themes

Scalar disruption, i.e., making big things small and small things big (technique: user-controlled hi-resolution motion-tracking cameras)

5) Delivery mechanisms

- Animation that speaks real-time to audience, i.e., motion capture device. Screen shows swimming fish, but one fish has unique quality to address audience. It is a performer (not unlike our own Mr. Fish) who is equipped with a wearable computer that allows him to manipulate on-screen fish and address individual students as protagonists/antagonists in a gentle and fun way. Provides rarely-seen interaction with students in a high-tech manner. Additional video screens will also provide substantive visual resources(satellite imagery, underwater imagery, offshore buoy data) to augment/reinforce live presenter.

- A preferred alternative is for scientists to present directly to kids. Many barriers exist to the implementation of this approach, including time available to scientists, their skills as presenters, and the need to do more or less the same thing over and over again. If this approach cannot be made to work, alternative means must deliver the aspirations portion of the message, i.e., If this is really exciting to you, you can become a scientist, or contribute in some way to this endeavour.

- There is an opportunity to create an interconnected experience using a personalized badge/card with an ID code that would allow prior visitors access to ‘special’ areas of GMRI Web site where they could share their observations, creations, IM chat communications, etc.

- Stories and vignettes will be an important means of concept delivery

- Integrating and interweaving opportunities for imaginative fantasy (i.e. addressing patrons’ desires as well as interests, wants, needs) with knowledge sources and problem solving experiences enriches, amplifies, reinforces and extends both the on-site experience and the follow up behaviour (Cagan & Vogel, 2001).

Not all of these initial ideas made it beyond this early stage; real-time animated fish speaking to the audience and using handheld devices versus fixed interfaces were both left behind after extensive secondary research. The notions of recognizing each individual, personalizing the experience and having scientists present directly to students, ideas which emerged both from secondary research and from brainstorming sessions, evolved into overall guidelines for the design of both the on-site experience and the follow-up Web site interaction (Falk & Dierking, 1992, 2000, 2002).

Target Audience and Design Process

A critical strategic decision at this point was to focus on a specific audience in Phase 1: middle school students, primarily 5th graders. This has been one of the most important decisions of the entire project and one that is difficult to reach on many projects. Clearly and specifically defining, focusing on, and then involving end-users in a collaborative, iterative design/development process is critical to the success of complex, technology-enhanced educational projects. These are points that are often made and sometimes acted on: the involvement of users is a mantra that is heard frequently. The experience of the development team on this project has proven that defining the target audience as specifically, even narrowly, as possible, is of similar importance. Several interesting results have come from this decision that are discussed in the Conclusions of this paper.

Building upon these strategic guidelines, GMRI engaged the services of the Web and interactive experience design firm Image Works/XhibitNet to lead the concept design and requirements gathering process, along with the aquarium and exhibit design firm Lyons/Zaremba Inc. and long-time GMRI designer/illustrator Michael Lewis to help visualize the facility.

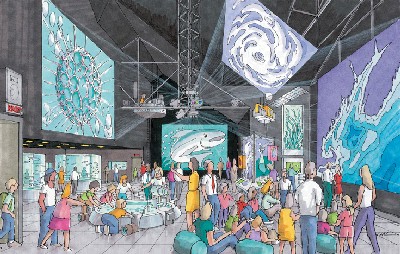

Fig 1: Early concept sketch of facility

Image Works/XhibitNet brought ten years of experience in user-interface and

technology development to the project, along with a background in science education

and communication. As

an early proponent of user-centered collaborative design beginning in the early

1990s, the firm’s staff proposed a thorough but cost-effective design process.

Fig 2: Immersive presentation technology was an early facility design concept

GMRI Interactive Experience Design Process

Discover

- Conduct best practices research

Define

- Specify, prioritize, and document visitor profiles

- Develop draft content outline

- Brainstorm draft content-based visitor experience scenarios and designs Participants: project lead, architect, educator, student, interaction designer, exhibit design consultant

- Prioritize visitor experience scenarios

Design

- Storyboard visitor experience flow

- Determine research protocols

- Determine forms of prototypes (paper, on-screen, architectural models, manipulation models, etc.)

Prototype

- Produce and validate (for feasibility) interaction prototypes

- Pilot test prototypes and protocols

- Refine test approach

Test

- Conduct user experience prototype tests

- Dyad research (observe/facilitate pairs of users interacting with prototypes)

- Student team research (observe/facilitate 3 or more users with prototypes)

- Report results of research

- Finalize design prototypes

To begin the best practices research, Image Works and GMRI education staff conducted research on dozens of related informal science education projects around the world; both secondary research and site visits to museums, aquariums and science and technology centers in Boston, New York, Chicago, the San Francisco Bay area and other locations. More than four months of concentrated best practices research was conducted as a basis for conceptual planning on the facility, exhibit design and the use of the Web to support the visitor experience. A milestone in this process was attending Museums and the Web 2002 where many of the ideas already under consideration were discussed, critiqued, debated with colleagues and compared to related efforts elsewhere around the world. A workshop conducted by Slavko Milekic and later his consulting on the project were influential at this early stage, as were pilot handheld projects at the Exploratorium (Semper & Spasojevic, 2002) and elsewhere. In developing technology for informal learning, the value of connecting, sharing insights, successes and failures with peers, is immense.

Concurrent with the last two months of this best practices research was a series of more than a dozen exhibit experience concept sessions led by the authors. Out of these sessions emerged an overall topic, an initial set of proposed exhibits and an experience flow storyboard of the student activities. The topic selected was the keystone species of the Gulf of Maine, the Atlantic herring. Although not a particularly charismatic species or topic, the team felt that it would best represent the science actually being conducted at GMRI and that if developed properly, it could make a fully engaging introduction to marine research for the middle school audience.

After determining the prototype test protocols and forms to be used, our next step was to create a series of progressively more refined prototype interactive exhibit experiences. We began by creating a simple pilot test using five prototype exhibits. Eleven students and their teacher were brought into a television studio which served as our testing facility throughout the project. Detailed observations were recorded by the project team, along with video and audio documentation. The outcomes of this pilot drove the design of a more elaborate set of five prototypes which were tested two months later with forty seven students and their teachers.

Fig 3: Students with fish, rubber gloves and paper prototypes

Prototypes were revised between sessions to rapidly give the design team a sense of how major variations influenced usability, learning outcomes and students’ feelings of understanding and accomplishment. At the end of each session, students and teachers were interviewed about their experiences and insights, followed by an extensive debriefing and discussion with all observers.

Fig 4: Second stage prototype using digital microscope

The result of this process was a detailed requirements document specifying design principles, usability and learning issues, a step-by-step exhibit experience and Web site flow, and a proposed technical architecture for all major systems. Out of this document and the prototype tests which led to it, the next generation of high-fidelity prototypes was created. Designated LabVenture Stations by the design team, these dual-screen, computer-based interactive kiosks embodied almost two years of design research and revisions.

Fig 5: Students testing LabVenture Station prototype

Platform Flexibility

In thinking through the LabVenture Station approach, the design team was mindful of the need to implement a platform that would allow for maximum flexibility in delivering a wide range of content, as science content to be translated on the platform will change once each year. While the bulk of our time, energy and financial resources was directed at the Atlantic herring topic, now officially named the Mystery of the X-Fish in order to capture the spirit of investigation and inquiry of the activity design, a modest commitment to testing a second, completely unrelated content stream was also made.

Based on research GMRI is involved with, we also explored the question of delivering content about Biological Nanotechnology on the LVS platform. The self-organizing of calcium and silica into scales and shells at the scale of a billionth a meter is about as different from a 9” baitfish as any two topics could be. In prototyping LVS screens and thinking about likely activities, we were encouraged to conclude that the LVS platform could accommodate a breadth of marine science content. In the schematic design phase, we theorized that the platform would allow for one topic to be taught in the morning, while an entirely different topic could be featured on the LVS platform in the afternoon.

Fig 6: Biological Nanotechnology LabVenture Station prototype

Evaluation

GMRI retained the Program and Evaluation Research Group (PERG) at Lesley University to conduct front-end and formative evaluations in early 2004. Summative evaluation services will be contracted for completion during the 2006 school year.

Front-end and Formative Evaluations

The front-end and formative evaluations began in January 2004, comprising 15 days of data collection to establish:

- students’ knowledge about and interest in aquatic sciences and Gulf of Maine ecosystems;

- students’ knowledge, understanding, and perceptions of science and the process of scientific inquiry;

- teachers’ knowledge of science and confidence in teaching science

- science teaching needs and available resources

- teachers’ perceptions about the appropriateness of the PI exhibit content and technology for students.

PERG researchers contacted teachers who would be bringing classes to the February, 2004 prototyping sessions, describing their evaluation role in the development process, and proposing student groupings to best analyze the results of the prototype testing. During the prototyping sessions, two PERG researchers observed and documented each student interaction with the LabVenture Station activity called What Do X-Fish Eat, and then interviewed each student group. They followed up the two test days with lengthy conversations with each participating classroom teacher and prepared a draft report.

PERG Summary of Evaluations

Overall, we commend you on developing an activity station that is so rich that it fully engaged the range of students we observed, provided the tools they needed to weigh the available evidence, and encouraged their use of quite sophisticated reasoning skills to form their conclusion. We believe that the session you are planning that will involve all participating students once they have completed their exploration of the activity stations will provide students the opportunity to compare their findings and discuss the evidence sources they used. (Baldassari, 2004).

PERG Comments on Student Engagement

This activity, as currently designed, is engaging and provides opportunities for students to collaborate as they examine the evidence and select samples to preserve. In fact, in most teams, most if not all students were actively involved during this stage of the investigation…

Students’ continued interest in knowing what x-fish eat is clear evidence that the station activity was an engaging, appropriately designed investigation for this age group. Their thinking did not stop when the activity ended.

These students came away from their experience very curious. When they finished the station activities, they had many new questions. Some were asking more sophisticated questions about what x-fish eat. . . . Students were eager to return and do additional marine research.

PERG Comments on Program Strengths: An Excerpt

Throughout the report, we have noted a number of the strengths of the design and development of the station prototype. Here we want to briefly outline the ways in which we think it is well designed and presents a very valuable learning experience for students.

- What Do X-Fish Eat? is developmentally appropriate for 5th and 6th-grade students.

- The activity station fully engaged students in the scientific process.

- The mystery presented and the design of the investigations supported collaboration.

- The activity station did contribute to students’ learning and appeared to promote their interest in marine research

- Although still a prototype, the station was technologically reliable during both testing days.

Teacher Quotes

“Overall, I think the concepts and how the prototype was set up - it’s a winner for a strong educational visit. This concept is so unique and beneficial to kids that visit. The thinking part, the processing kids have to go through is unique to this facility. I was enthralled.”

“Socially, I felt it was a very good social interaction and shows how scientists have to work together and dovetail off of each other’s thoughts. More than answers - but the process of what scientists go through and how they work together to help each other.”

“There was good communication between the kids for the most part. They were asking significant questions….They worked very well together. Some kids went beyond what they have done in class. …”

“The x-fish activity, to watch students engage in something that was new and foreign to them, in terms of equipment and technology, reinforced the process I’ve been using in the classroom.”

“They said ‘we can’t wait for oceanography’…

“I had several parents thanking me for including kids in the activity.”

Teacher Quotes

“As a team, it was fun to figure it out. We all got to experiment with things on the screen and talk it through as a group.”

“I thought it was challenging - so I liked it. I like challenges. It’s good to have a challenge once in a while.”

“I had fun doing research. The x-fish station was really hard to work as a team; it was tricky. We used our minds.”

“I think you learn that if you are with a team you need to use teamwork. I learned that if you worked together you could find more things that you didn't really know.”

“It makes you more independent. There was no adult to help you. It's fun to do stuff on your own. Sometimes teachers give you all the information. I liked that you experimented yourself.”

Fig 7: GMRI staff at the completed Cohen Center for Interactive Learning

The Completed Experience Design

Four years later and after thousands of hours of design, testing, learning evaluation, technical specification, programming, content implementation, hardware and software installation, testing and debugging, this flexible learning platform has been fully realized. The result is a long-term learning experience targeted to all 5th and 6th grade students and teachers in Maine. The experience begins with a 2-hour field trip visit to the GMRI Cohen Center for Interactive Learning. Here students conduct their own in-depth, simulated marine research investigations and experiments, including handling and observing both live and dead specimens. These investigations are facilitated through the use of networked, high-definition interactive computer research stations with digital video dissecting microscopes, video notebook report cameras and aquarium schooling tank cameras. Teams of students make virtual trips into the Gulf of Maine to record scientific data using actual echogram images, and to conduct commercial fishing expeditions based upon a realistic economic simulation. Students record their observations with their digital tools and present their findings in summary peer review sessions. All of the students' hypotheses, evidence and findings are saved to individual personal science notebook Web sites which they and their teachers and parents can access at school or home.

The personalized, database-driven Web content management system created by Image Works for the project encourages students to participate with GMRI scientists and staff and to contribute to ongoing exploration of Gulf of Maine topics. On their personal Web sites students can annotate, update and export all of their digital movies and images to PowerPoint, iMovie or other multimedia presentation tools to create additional extended research reports integrated with other class projects and materials. The Web site also provides additional topical information, suggested reading, updated news, links to other interesting marine science topics, and a variety of interdisciplinary classroom-tested activities and in-depth projects that teachers can adapt for their own curricula. These activities tie locally relevant science content to other subjects, including math, art, social studies and history projects.

Summative Evaluation

A summative evaluation, launching in Q2, 2006, will examine the impact of the program and the extent to which The Mystery of the X-Fish meets its goals for teachers and students. Evaluators will collect data and report about whether and how the equipment and presentations, investigations, and follow-up experiences:

- communicate program content;

- promote the desired attitudes;

- generate interest in follow-up activities; and

- contribute to use of Web-based science resources.

Evaluators will visit the Cohen Center program to:

- observe groups of students for their use of the scientific process and level of interest and engagement at the exhibit stations, the ways in which they apply what they learned at the four stations to the overall mystery/mission; conduct informal interviews with students and teachers on-site;

- review student products on-line;

- interview a sample of teachers about student learning, their perceptions and use of program components, age appropriateness of materials, the extent to which pre/post-visit activities, Web-based resources, and digital portfolios match their own and students’ needs and interests, and their suggestions for revisions;

- disseminate pre-program and follow-up surveys to a sample of students to explore attitudes about aquatic education, their interest in science as a possible career choice, and what they believe they learned through the program;

- measure students’ interest in and knowledge about aquatic resources and Gulf of Maine ecosystems, understanding and use of the scientific process to conduct inquiries, and recognition of science as a viable career possibility;

- gather teachers’ perceptions of the relevance of Maine aquatic education for their students, and their perceptions about what students have learned;

- check the extent to which teachers use program materials including interdisciplinary activities and students’ digital portfolios in classroom teaching;

- make changes in the exhibit to better meet the needs of the audiences.

In addition to continuing the summative data collection activities, evaluators will:

- visit the Cohen Center program to observe students and teachers and conduct focus groups with students to collect data about the effectiveness of exhibit stations, the match between program components and their interests, and what they have learned;

- review GMRI visitor statistics/demographics and data concerning student use of the Web site (GMRI);

- interview GMRI staff about their perceptions about the program, student and teacher reactions, the teacher training program(s), and changes in program design;

- evaluate the extensibility of the model through talking with Cohen Center staff (including developers of the technology) as well as external experts identified by program staff.

Early Outcomes

GMRI began welcoming students to the Cohen Center in October, 2005. As of the writing of this paper, more than 1,500 5th and 6th-grade students have engaged with The Mystery of the X-Fish. An additional 2,500 students have been booked for programs between February and June, 2006. Based on current booking patterns, GMRI anticipates welcoming approximately 7,200 students over the calendar year, representing 50% of the 5th or 6th-grade student cohort in Maine. In 2007, GMRI expects to increase to 75% of the student body, and, in 2008, to reach our program goal of 90% of 5th or 6th-grade students in Maine.

GMRI employs a process of continuous feedback loops to monitor program progress and make improvements toward meeting our program goals. Current feedback loops include the formal external evaluation process described above, an ongoing on-task study, teacher evaluations solicited by GMRI following each visit, student thank-you letters, media reports and daily anecdotal observations recorded by program staff.

Sample Comments By Teachers Include

“Thanks for the wonderful experience at GMRI with the X-Fish. There hasn't been any field trip quite like it. The technology and the activities were very sophisticated, engaging, and perfect for our age group. It fit into our studies perfectly. We all loved it and our parent chaperones were quite impressed. The students had a wonderful experience and they continued to talk about it today. Over the course of the day today, many visited the Web site I had shown them ahead of time to re-experience the activities.”

“What a wonderful facility you have! The interactive nature of the presentation plus the strong tactile kinesthetic factor really "hooked" the kids, engaging both their minds and hands. I was very impressed with the design of the program that really did get the students thinking and acting like scientists. Back at school the kids spoke enthusiastically about their experience. As our neighbor down the hill I hope that this is just the beginning in what could be a long running relationship between our school and GMRI. Thanks you for hosting our school.”

Wow! The best field trip EVER!!! The students were totally engaged and the presenters were awesome. Thank you so much for a wonderful experience. Science has never been such fun and so meaningful.

Stendent Comments Include

“Thank you very much for giving our class the experience of being a marine scientist. I found it thrilling to hear that some glitter is made from fish scales! My favorite station was the one where you choose where to take a boat to drop a net.”

“I liked the recording part, because it was neat seeing it on the big screen! The dead fish was freaky, but it was cool being able to touch a real fish! I also liked the fishing station. It was so fun! P.S. Do you think 6th grade could go, because my best friend who is in 6th grade wants to be a marine biologist!!”

GMRI’s Advisory Group for Interactive Learning (AGILe), comprised of professionals in the fields of learning and technology, meets monthly to monitor feedback, discuss program enhancements and explore future directions.

Conclusions

One key to the success of this project has been very carefully, and even narrowly, defining the target audience, then sticking to building the experience for and with that audience. Several interesting results have come about from this very specific audience definition. First is that we were able to hone the experience so finely for this audience that it has proven to be successful even with a much wider range of ages. Preliminary testing of the learning experience during the soft launch with summer campers in 2005 indicated that both the cognitive and the affective learning experiences are effective with visitors in grades 2 through 8 and beyond. Campers became engaged, and remained engaged through a two-hour sequence of tasks. At the end of this sequence even the youngest campers were able to use language and verbalize and speculate on ideas related to their tasks. Additionally, by focusing limited resources on a specific strategic audience, GMRI has been able to create an experience with an impact, resonance and word of mouth value in the community that has generated a demand for broadening the audience, and the funding support, for the program.

Finally, we would like to reemphasize the value we found in connecting: sharing insights, successes and failures with our peers in the exhibit and educational Web design field. Our mantra coming out of this project has become learn from as many other successes and failures as possible, involve as many end-users and stakeholders as much as possible, and don’t make early designs and prototypes too precious.

References

Baldassari, C. and R. Sayko (2004). Gulf of Maine Research Institute’s Public Interface Prototype Activity Station Trials: What does the X-Fish Eat?. http://www.xhibit.net/PERG consulted January 30, 2006.

Dierking, L. D. and J. Falk (1992). The Museum Experience. Washington: Whalesback Books.

Dierking, L. D. and J. Falk. (2000). Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning. California: AltaMira Press.

Dierking, L. D. and J. Falk (2002). Lessons without Limit: How Free-Choice Learning is Transforming Education. California: AltaMira Press.

Semper, R. and M. Spasojevic. The Electronic Guidebook: Using Portable Devices and a Wireless Web-based Network to Extend the Museum Experience. In D. Bearman and J. Trant (Eds.) Museums and the Web 2002, Selected papers from an International Conference. Pittsburgh: Archives & Museum Informatics. 11-19. Available http://www.archimuse.com/mw2002/papers/semper/semper.html

Cite as:

Lishness A. and Hutchins D., Immersing Students in Research at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2006 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/lishness/lishness.html