Norman Lownds and Carrie Heeter, Michigan State University, USA

Abstract

Field trips to museums, science centers, children’s gardens and other sites can be powerful learning experiences for students of all ages. They are, however, limited by the short time that students spend at the science site. Educators at the 4-H Children’s Gardens wanted to change this limitation and design ways to maintain contact with students for much longer periods of time before and after their field trips. To accomplish this, the on-line Wonder Wall was created. Wonder Walls connect learners, teachers, off-site experts and students in real time and asynchronously to persistent, playful, moderated, spatial communication environments designed for collaborative learning. Participants compose or upload and position text or graphical “post-its” on the Wonder Wall. Wonder Walls are specialized environments which facilitate affect (a sense of mystery, fun, excitement, and importance) and cognition (reflection and formulating questions). Each Wonder Wall has a moderator who can attach answers to posts and stream real time audio. Wonder Walls are currently used by elementary school classes to connect the class with plant scientist “Dr. Norm” as a follow up for science field trips to the 4-H Children’s Garden. Fourth graders consistently log into the Wonder Wall before and after school and throughout the weekend. Some students have maintained contact with Dr. Norm for more than 8 months after their field trip. When fourth graders posted questions to the Wonder Wall, nearly two-thirds of their questions were wonderment questions. Many of their questions were deep questions showing that the students had thought carefully about the topic and were attempting to put together pieces of different and sometimes conflicting information. Wonder Walls accommodate both task-driven and performance-driven learners. Task-driven students think hard about the specific content and what to wonder about. Performance-driven students are more motivated by knowing the class and teacher will see their posts. Based on our initial studies it appears that the Wonder Wall can be an effective tool to maintain contact with students and teachers. Through the Wonder Wall we are cultivating interested visitors for tomorrow.

Keywords: Field trips, wonder, curiosity, questions

Introduction

Classroom field trips to museums, children’s gardens, science and nature centers and other sites can have many positive effects on students, including positive cognitive and affective learning outcomes (Riley and Kahle, 1995). Over the past twenty years there has been a considerable increase in the number of informal learning centers, including museums, children’s gardens, interactive science and field study centers (Dierking and Falk, 2000). In fact, there are reports that over twenty million elementary and junior high students take field trips to informal learning environments each year (Kubota and Olstad, 1991).

Field trips are regarded as effective teaching tools (Prather, 1989). Teachers have observed that field trips foster positive attitudes toward science in their students (Tuckey, 1992). Prather (1989) noted that field trips enhance students’ attitudes toward science as well as their information gain. Classes that performed better in the field achieved significantly higher scores on a knowledge test and gained more positive attitudes (Orion and Hofstein, 1994). Field trips tend to “catalyze, enrich or culminate” instructional units (Delaney, 1967), providing opportunities to illustrate and reinforce concepts, facts, and skills being taught (Keown, 1984). There are immediate outcomes to the field trip experience, including retention of knowledge (Knapp, 2000). Experiences that children have while participating in a field trip produce memories that stay with them long after the completion of the program (Knapp, 2000).

Post field trip classroom activities are essential for reinforcing experiences, facts, skills, and concepts learned during the field trip (Bitgood, 1991). However, there typically is little or no follow-up (Kubota and Olstad, 1991). Teachers seldom implement post-visit activities designed to provoke students to recall and extend their learning experience (Bitgood, 1989). Most teachers indicated that they would in fact do some type of follow-up, yet the results showed that there was very little done, less than the teachers had planned on (Griffin and Symington, 1997). While the benefits of post-visit activities could be substantial, very little research has been conducted on the influence of post-visit activities on student learning (Anderson, et al., 2000).

Thousands of students participate in field trips to the Michigan 4-H Children’s Gardens each year. To date, field trip follow up materials have been available, but their use has been limited. Educators at the 4-H Children’s Gardens wanted to see this change.

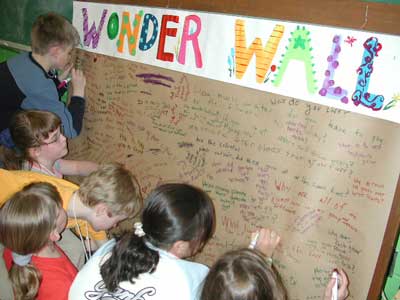

Field trips to the 4-H Children’s Gardens, similar to field trips to many museums, can range from as short as 1 hour to all day and even multiple days. Recently, we have placed increasing emphasis on day-long and multiple day field trips called Seeds of Science (Driscoll, 2004). Seeds of Science field trips are full day and typically consist of three separate visits, with each visit separated by a week or more. During these field trips students are encouraged to ask questions and to be curious and wonder about everything. To promote this sense of wonder and discovery, students use a Wonder Wall to ask questions and make observations.

Fig 1: Children at the Wonder Wall

Wondering does not stop when students leave the garden, but is encouraged as an important activity between field trips. Therefore, teachers work with their students between field trips to develop additional questions as they reflect on the field trip activities and as they prepare for the next visit. In this model, ways to recognize students’ questions and answer them are essential to promoting even greater curiosity and wonder, interest and engagement. Ongoing field trip follow up connections may be as important as the field trip itself.

The on-line Wonder Wall was developed in response to the need for effective ways to establish and maintain connections and ongoing interactions with students following field trips to the 4-H Children’s Gardens. This was designed to be an extension of the original Wonder Wall, but enhanced and expanded so that students could use it whenever they had additional questions or thoughts related to their field trip.

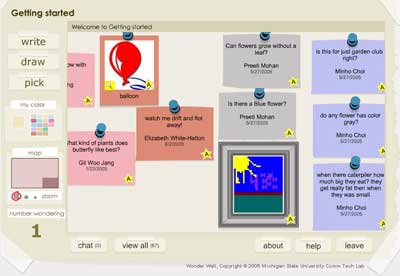

Wonder Wall

Wonder Walls connect learners, teachers, off-site experts and students in real time and asynchronously to persistent, playful, moderated, spatial communication environments designed for collaborative learning. Participants can post questions and information to the Wonder Wall in several formats (Figure 2):

Write: Space to post written questions and comments. Students simply type their questions and then post them to the Wonder Wall. Questions and comments can include URL’s that will be active links to those Web sites.

Draw: Students can draw pictures or create them using the stamp tool. Pictures can be colored and customized.

Pick: Students can choose pictures from the image gallery or upload their

own pictures.

Fig 2: Getting started

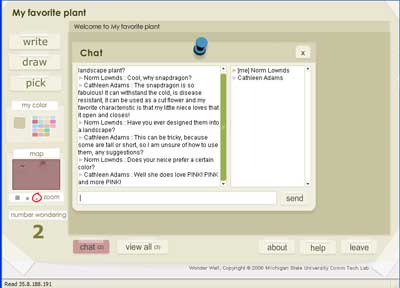

In addition, when more than one person is connected simultaneously, students can Chat in real time.

Fig 3: Samples of chat

To ensure that the questions students post are answered, each Wonder Wall has a moderator who can compose answers to posts and stream real time audio.

As part of their Seeds of Science field trips, students and teachers were introduced to the Wonder Wall and shown how to use it. They were encouraged to use it both in school and out of school when they had questions and comments about the things we had done at the 4-H Children’s Garden.

Results

Fourth grade students used the Wonder Wall extensively following a field trip to the 4-H Children’s Gardens. Approximately 80 students were exposed to the Wonder Wall and used it between and after field trip visits. During a three-week period at the end of the school year, Wonder Wall use was as follows:

- Initial daily access was between 7:00 and 7:30 am every weekday

- Last daily access was between 9:00 and 9:30 pm

- there was an average of 40 daily posts outside of school time

- Maximum posts outside of school hours on a single day was 95

- Minimum posts outside of school hours on a single day was 15

- Approximately the same number of posts were made on Saturday and Sunday as weekdays

- When students were allowed to make posts during school hours the daily number of posts was over 100

- Students prearranged with classmates to “meet” on the Wonder Wall in the evening or on the weekend to chat

- Students stayed on task and asked questions or chatted about plants

- Students read posts by other students and often answered each others’ questions

Interviews with students indicated that almost all students liked to use the Wonder Wall, especially when their teacher gave them time to use it during school. In addition, students really liked to have their questions answered and would always go back to the Wonder Wall and check to see what answers had been posted.

Students posted hundreds of questions on the Wonder Wall. The importance of encouraging questions and providing space to ask them cannot be overemphasized. Children commonly express their curiosity and wonder by asking questions (McWilliams, 1999; Doris, 1991; Chukovsky, 1963). Chin et al (2002) believes that questioning lies at the heart of scientific inquiry and plays a significant role in meaningful learning and motivation. Questioning is a thinking processing skill that is structurally embedded in the thinking operations of critical thinking, creative thinking and problem solving (Ennis, 1985; Hayes, 1981). It also is comprised of smaller microthinking skills of recall, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation. Questions are the language of wonder and show what students want to know and what they are curious about (Commeyras, 1995). Questions reveal the level of students’ thinking and conceptual understanding (White and Gunstone, 1992; Woodward, 1992; Watts et al, 1997; Gardener, 1991). Questions indicate that students have been thinking about ideas presented and have been trying to extend and link them with other things they know (Chin et al, 2002). While students question they are thinking, seeking meaning and connecting new ideas to familiar concepts (King, 1994). Questions enable students to realize a paradox or puzzle, or gap in their knowledge (Biddulph and Osborne, 1982; Chukovsky, 1963).

Because students’ questions are so important, the types of questions that students asked were examined. Questions were classified as either basic information or wonderment questions. Basic information questions are generally minimum difficulty; low level questions that request further factual or procedural information about the garden or the activities. Wonderment questions reflect curiosity, puzzlement, skepticism, or a knowledge-based speculation (Scardamalia and Bereiter, 1992). Wonderment questions are associated with a deep approach to learning science, whereas basic information questions are related to a more surface approach (Chin, et al., 2002).

Students consistently ask over 65% wonderment questions on the Wonder Walls. This is a very high percentage compared to previous studies that reported students averaged 14% wonderment questions during the course of five different hands-on activities (Chin, et al., 2002). A previous study at the 4-H Children’s Garden found that 2nd and 3rd grade students averaged equal amounts of wonderment and basic information questions on the Wonder Wall (Driscoll, 2004).

Wonderment questions were further divided into the following categories according to Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956):

- Comprehension questions: Seek explanations of things not understood (Chin, et al, 2002)

- Application questions: Use previously learned information in new and concrete situations to solve problems that have single or best answers

- Analysis questions: Break down and organize information into its component parts and develop conclusions by recognizing patterns and finding generalizations

- Synthesis questions: Creatively apply existing knowledge and skills to produce an original whole

- Evaluation questions: Judge the value of material based on personal opinions and values

Typically 50 to 65% of the wonderment questions were comprehension, 10 to 20% application, 5 to 25% analysis and about 1 to 3% synthesis. In general, the complexity of questions increased as students used the Wonder Wall more times.

Samples of the questions students asked are presented in Table 1.

| Type of questions | Specific questions |

|---|---|

| Comprehension | Do some plants have a poison smell? What is the seed coat made of? Does a flower have to grow its sepals? What do insects do for flowers? What do insects do for flowers? Are there more plants that are small or big? Is there such a thing as bubble gum plants? What plant has big leaves? Are plants healthy for you? What makes a plant smell good? Do a lot of people kill plants? What do insects do for flowers? |

| Analysis | Is chlorophyll in every plant? How can a maple tree make red pigment? Why do people like flowers? Do plants think? How does the anther produce pollen? How does the flower change and produce a fruit? What is the most important part of a root? What if there is a flower that has the pistil and stamen separated? How does the plant just get CO2? They don’t have lungs do they? |

| Synthesis | If the plant fell off and the roots are still alive will the plant still grow? If an animal were to make a hole through a tree (but only through the middle and not the sides) would the tree die? If plants make glucose why do they need nutrients from the ground? |

Table 1: Sample student questions

Often, when moderators answer student questions they pose new questions and direct students to think more about their question or questions related to it. When the moderator posed additional questions in his/her answer, students were very diligent in answering them and enjoyed these exchanges with the experts.

| Student Question or Statement | Expert Response |

|---|---|

| With my lettuce project, my lettuce is growing very well, but I can’t see the orange dye in it yet. | Are you testing orange dye in one and just water in the other? Did you mix water in with the dye? If you did, you could try adding less water and more dye this next time to see if that makes a difference? |

I’m wondering why me lettuce (freckles) is growing sideways? Is that a good thing? I got your answer about my lettuce (freckles) growing sideways. Yes it is by a window. I think it might be good because when we were growing lettuce at the MSU gardens freckles was growing sideways just the same as it is doing now. |

Hmmmm.... Is your cup of lettuce by a window? If so, do the leaves seem to be heading in that direction (toward the window)? If that is the case, perhaps you could hypothesize why freckles is growing sideways. What do you think? So, why do you think that the leaves might be growing toward the window? Think about what the leaves for the plant and why that window is so important. I'm excited to hear your thoughts! This is fun! |

Why do pansies have blue pollen?

I got your answer on my blue pollen question. I’m not sure why either, but I think it might be because the flower is such a strong color (blue/purple). P.S. Please write back with your guess. |

You know that's a great question. I have asked that myself before and I am just not sure. I could come up with a hypothesis, but I'd like to hear your guesses first. Why do you think they have blue pollen? Ok, you know how chlorophyll is a pigment that is found in leaves. Well, we know that chlorophyll gives leaves their great green color. There are all kinds of different pigments with crazy names. There are a group of pigments called anthocyanins that could be responsible for making that pollen blue. Why in those pansies (or were they petunias) that you were observing... I'm still not sure. What advantage might the petunia have if its pollen is blue and not yellow? Any thoughts? |

| Try putting lemonade and pop in two different cups with seeds. If you find out which grows better, tell me. | I don't have lemonade. Why don't you give it a shot and report back to me. Be sure to make a hypothesis first! |

Table 2. Student generated questions and ongoing conversation with an expert on the on-line Wonder Wall.

Finally, some students continued to use the Wonder Wall to ask questions even months after their field trip and even though they were studying very different subjects. Sometimes their later use was just to say “Hi”, while at other times they were asking science related questions.

Summary and Implications

The Wonder Wall has proven to be a very effective tool for enhancing and expanding field trip experiences at the 4-H Children’s Gardens. Students enjoy using the Wonder Wall, and use it before, during and after school on a daily basis. The questions they ask are nearly two-thirds wonderment questions, many that are very thoughtful and show analysis and synthesis. Students value the answers from scientists and look forward to having their questions answered. When prompted to think more about their questions or to think in different ways, students will ‘converse’ with the expert, often exploring a topic in much greater detail. Preliminary data suggests that these interactions result in greater content knowledge and greater comfort with asking questions. In short, the Wonder Wall is making it possible to stay in contact with classes long after their field trip and to create connections that we believe will last for years. The Wonder Wall is enabling us to go far beyond the field trip and the classroom to be with students as they process ideas and wonder.

We are certain that the Wonder Wall can be an effective tool for any museum, science center, children’s garden or other field trip destination to remain in contact with visitors long after the field trip has taken place. Discover how the Wonder Wall works and explore how you might use it in your institution to go beyond your current field trips.

References

Anderson, D., B. Lucas, I. Ginns and L. Dierkling 2000. Development of knowledge about electricity and magnetism during a visit to a science museum and related post-visit activities. Science Education 84:658-679.

Biddulph, F. and R. Osborne 1982. Some issues relating to children’s questions and explanations. LISP(P). Working Paper No. 106, University of Waikato, New Zealand.

Bitgood, S. 1991. What do we know about school field trips? What research says… ASTC Newsletter Jan/Feb:5-6,8.

Bitgood, S. 1989. School field trips: An overview. Visitor Behavior 4:3-6.

Bloom, B., M. Engelhart, E. Furst, W. Hill, and D. Krathwohl 1956. Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. New York, Longmans Green.

Chin, C., D. Brown and B. Bertram 2002. Student-generated questions: a meaningful aspect of learning in science. International Journal of Science Education 24(5):521-549.

Chukovsky, K. 1963. From two to five. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

Commeyras, M. 1995. What can we learn form students’ questions? Theory Into Practice 34(2):101-106.

Delaney, A. 1967. An experimental investigation of the effectiveness of teacher’s introduction on implementing a science field trip Science Education 51(5):474-481.

Dierking, L. and J. Falk 2000. One teacher’s agenda for a class visit to an interactive science center. Science Education 84:524-544.

Doris, E. 1991. Doing what scientists do: Children learn to investigate their world. Portsmouth, Heinemann.

Driscoll, E. 2004. Fostering wonder and curiosity: Immersion field trips in the Michigan 4-H Children’s Garden. East Lansing, Michigan State University.

Ennis, R. H., 1985. Goals for the critical thinking curriculum. In A.L. Costa (ed.) Developing minds: A resource book for teaching thinking. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum development.

Gardener, H. 1991. The unschooled mind. New York, BasicBooks.

Griffin, J. and D. Symington 1997. Moving from task-oriented to learning-oriented strategies on school excursions to museums. Science Education 81:763-779.

Hayes, J.R. 1981. The complete problem solver. Philadelphia: Franklin Institute Press.

Keown, D. 1984. Let’s justify the field trip. The American Biology Teacher 46(1):43-48.

King, A. 1994. Guiding knowledge construction in the classroom: Effects of teaching children how to question and how to explain. American Educational Research Journal 31:338-368.

Knapp, D. 2000. Memorable experiences of a science field trip. School Science and Mathematics 100(2):65-72.

Kubota, C. and R. Olstad 1991. Effects of novelty-reducing preparation on exploratory behavior and cognitive learning in a science museum setting. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 28(3):225-234.

McWilliams, S. 1999. Fostering wonder in young children: Baseline study of two first grade classrooms. National Association of Research in Science Teaching, Boston, MA.

Orion, N. and A. Hofstein. 1994. Factors that influence learning during a science field trip in a natural environment. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 31(10):1097-1119.

Prather, J. 1989. Review of the value of field trips in science instruction. Journal of Elementary Science Education 1(1):10-17.

Riley, D. and J. Kahle. 1995. Exploring students’ constructed perceptions of science through visiting particular exhibits as a science museum. Presented at National Association for Research in Science Teaching.

Tuckey, C. 1992. School children’s reactions to an interactive science center. Curator 35(1):28-38.

Watts, M., G. Gould and S. Alsop. 1997. Questions of understanding: categorizing pupils’ questions in science. School Science Review 79(286): 57-63.

White, R. and R. Gunstone 1992. Probing understanding. London: Falmer Press.

Woodward, C. 1992. Raising and answering questions in primary science: some considerations. Evaluation and Research in Education 6(2/3): 15-21.

Cite as:

Papers: Lownds N. and Heeter C., Connecting Beyond the Field Trip: The On-line Wonder Wall, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2006 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/lownds/lownds.html