Lois McLean and Rick Tessman, McLean Media, USA

http://www.contentclips.comAbstract

Now that digitization projects are relatively commonplace within cultural institutions, many organizations are finding the need to move beyond simply making database-driven collections available on-line towards providing tools and services that make these resources more useful for specific educational audiences and settings. With research funding from the National Science Foundation’s National Science Digital Library (NSDL), the authors are creating and evaluating a prototype Web-based learning environment called Content Clips. This study is examining the issues involved in building a Flash-based template system to let elementary teachers and curriculum developers select, build, customize, and assign learning activities to a class, group, or individual student. The project specifically addresses a current gap in research: how to increase the educational impact of digital libraries at the elementary level. While the research focus is life science content for Grades 3-5, findings will have broad application for other content areas, grade levels, and educational settings.

Keywords: digital libraries, interactive learning, K-12 education, multimedia, Flash templates

Introduction

Imagine having the ability to dynamically incorporate diverse digital media objects from one or even multiple Web-based digital collections into a single multimedia learning activity, while leaving the objects themselves intact on their host servers. Many digitization projects have made resource collections of images, documents, audio, and video available on-line, and some Web sites let users gather selected resources into personal sets or folders. However, few on-line collections offer individual users the ability to select, save, and manipulate objects through a single, Web-based dynamic interface or provide a way to place these objects directly into on-line learning activities, such as categorizing objects, playing matching games, or building virtual worlds.

Making digital versions of at least some of their holdings available on-line through a Web portal is now a common and even expected practice among large museums and other institutions. And, in recent years, the infrastructure to support these efforts has now reached the level of maturity that even small institutions can embark on collection digitization and presentation projects.

Best practices are now in place to guide the technical steps required, and content management systems and other off-the-shelf-software solutions are available for many of the common challenges encountered in such endeavors. Cataloguing methods have evolved to allow interoperability through the adoption of metadata standards. Hardware innovations have made it easier and less costly to store and deliver large quantities of digital data, and an increasingly sophisticated public is both able to access and eager to find on-line content that was once only available in a bricks-and-mortar setting.

The educational resources that museums make available on the Web vary widely but tend to fall into several distinct categories, including collections, on-line exhibitions, lesson plans, learning activities, and tour-related information such as pre- and post-visit materials for teachers. In an analysis of 100 randomly selected U.S. art museum Web sites, Varisco and Cates (2005) found that more than 50% of the museums had on-line collections or exhibits, but only a little more than 25% offered lesson plans and learning activities. While a museum’s on-line presence often represents only its own internal collection, many institutions are joining federated digital content organizations such as the California Digital Library or the National Science Digital Library to make their digitized content more widely available.

When requesting funding or other support for digitization projects, institutions often speak glowingly of the educational benefits of placing their collections on-line. Indeed, on-line collections from museums, libraries, archives, and other cultural institutions can be a treasure trove of resources for teachers and learners alike. However, to realize this potential fully, museums and other institutions are coming to recognize the need for innovative ways to enhance the educational impact of their digital collections.

The National Science Digital Library Effort

The National Science Digital Library (NSDL) (http://nsdl.org) is the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) on-line library of exemplary resources for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education and research. It was developed through an annual grant program and now offers a free, organized, public portal to collections and services from such institutions as universities, museums, publishers, and government agencies.

NSDL Project Examples

Any institution with a relevant collection may join the NSDL as a resource contributor, regardless of whether they have received NSDL funding, as long as its collection meets minimum metadata standards (Dublin Core) for Open Archives Initiative (OAI) harvesting. Aimed at a broad audience, efforts of NSDL-affiliated projects can be seen at Web sites such as the following:

- The WGBH Foundation’s Teachers' Domain (http://www.teachersdomain.org)

- Cornell's Macaulay Library Digital Library of Animal Behavior (http://www.animalbehaviorarchive.org)

- The Digital Library for Earth System Education (DLESE) (http://www.dlese.org)

- The University of Arizona’s Tree of Life Biodiversity Project (http://tolweb.org)

- The Exploratorium Digital Library (http://www.exploratorium.edu/educate/dl.html)

History of the NSDL

Since its inception in FY 2000, the NSDL program has made more than 200 awards in four categories: Collections, Targeted Research, Services, and Pathways. Among competitive NSF grant programs, the NSDL is unique. In particular, while all project proposals must pass a highly competitive peer review process, once a project is funded, its team members are then encouraged to take an active role in the growing NSDL community. Rather than pursuing their R&D efforts in isolation, whenever possible projects are expected to collaborate and share expertise with the community to create, select, distribute, and evaluate on-line resources. NSDL community members participate in several working committees that focus on key issues such as technology, standards, and evaluation, and all members are invited to gather at an annual meeting for program updates, workshops, presentations, poster sessions, and other networking opportunities.

Moving Beyond Digitization And Discovery

The course of the NSDL’s development appears to parallel the broader adoption pattern of digitization projects in general. In the early stages, projects place a necessary emphasis on collection building and on technical issues such as image resolution, interoperability, metadata standards, and intellectual property concerns. However, once these challenges are successfully addressed and related policies are established, many institutions then move towards contextualization - adding complementary tools and services that make the collection more useful for specific purposes and different audiences. And, without supporting services and tools specifically designed for K-12 audiences (including specialized metadata tagging), collections alone are rarely very useful in educational settings. Therefore, a trend appears to be developing within the NSDL and other institutions: shifting away from the almost exclusive emphasis on resource discovery and towards making resources more useful in educational contexts.

As part of this trend, the NSDL community is gathering a growing body of research concerning how teachers use Web-based resources, what they want in a digital library, and how digital libraries can be improved to address their needs. However, even though several NSDL projects are exploring ways to help K-12 educators in general take advantage of on-line collections; for example, by building computer-based tools for aligning on-line resources with educational content standards, most large-scale efforts have focused on teachers and students in middle school grades and above. Although our own research will have applications for a wide range of content areas and grade levels, we are particularly interested in how Web-based digital libraries can also be incorporated into elementary education, where they can support a broad range of activities from concept learning to independent inquiry.

Learning Object Granularity – Context Versus Reusability

One purpose for building digital libraries is to make learning resources created in one context more widely available for other users and purposes. Reusable learning objects have been the focus of much discussion among instructional designers and curriculum developers in recent years. Learning objects are sometimes defined as instructional resources that can stand on their own outside of their original context.

Learning objects can be placed along a continuum of granularity, ranging from a content asset (usually a single digital file, e.g. jpeg, .wav, etc.), to a lesson, course, or complete learning environment (Wagner, 2002). As objects become more granular, they may lose context, but they can be used in a wider variety of learning situations. As context is added, learning objects become more useful for a specific audience but less reusable in varied settings.

Within the NSDL, which is essentially a collection of collections, resources reflect a wide range in their degree of granularity, including Web sites, articles, units of study, lesson plans, animations, data, and images. In art or history museums, resource collections are typically more granular and homogeneous.

To put objects in context, museums typically develop curated exhibitions and educational activities, such as docent-led tours that focus on selected objects, to reflect a specific theme or topic area. While building a database of digitized objects may make them more accessible and reusable in varied contexts, it can also have the effect of de-contextualizing them or separating them from objects to which they are related thematically or from the physical setting in which they were originally viewed.

From Start With A Story To Start With The Stuff

For many years, we (as partners in McLean Media) have produced educational videotapes, videodiscs, and CD-ROMs for publishers, museums, and other organizations with an educational mission. Most of our production work for these projects involved what we call the Start with a Story approach, which means that we were often looking for a visual image, sound, or video clip to illustrate a specific concept in a client-approved script. For example, to provide the visuals for a series of documentary-style videos to accompany a textbook, we needed to find such diverse objects as a photo portrait of Eleanor Roosevelt, a speech by Jane Addams, and a painting that depicted an American Indian wearing a Peace Medal. For these documentary-style videotapes, the objects were drawn from diverse collections but were locked into their new context, a narrative about specific individuals.

In an assignment to create lesson plans, offline activities, and on-line interactive games for the Sacramento History Online digital library project (http://www.sacramentohistory.org), we faced almost the opposite situation. The four institutional partners in this collaborative project selected and digitized approximately 2,000 objects to fit the broad themes of the history of the Sacramento region’s transportation and agriculture, so our task required adopting an approach we call Start with the Stuff (a term used or perhaps even coined by a history museum curator). In this case, Start with the Stuff meant looking at the diverse items in the digitized collection (including photographs, documents, and ephemera) and then identifying those objects that were iconic or related to topics in the Grade 4 California history-social science standards. We then built the learning resources around these key objects. Although objects in the larger, searchable collection could be viewed, downloaded, or printed individually, and therefore used in different contexts, we did not directly call any objects from the database into the on-line learning resources.

The Content Clips Project

In our current research effort we are looking at how essentially content-free templates can dynamically incorporate individual media assets into learning activities for elementary education. Our approach is intended to identify practical and cost-effective ways for digital libraries to move beyond providing portals and searchable interfaces for the discovery of individual digital objects toward creating a framework that supports customizable, interactive learning experiences. Such experiences would offer opportunities for learners to make meaningful connections among individual items within a single collection or across distributed collections of federated content.

With funding from the NSDL, several organizations, including McLean Media, are developing services and tools to help K-12 educators take advantage of on-line collections in the classroom. As principal investigators for an NSDL Targeted Research Project entitled Creating Interactive Educational Activity Templates for Digital Libraries, NSF-DUE 0435464, we are examining the feasibility of using a Flash-based template system that draws from on-line digital collections to create Web-based educational activities. Our study specifically involves developing and evaluating the prototype for an on-line learning environment called Content Clips, which lets teachers and curriculum developers:

- select individual media assets, including images, sounds, and video clips from an on-line collection;

- build learning activities that incorporate these assets; and

- assign assembled activities to a class, group, or individual student. Students access their assigned activities through a Flash interface.

Another key element of the research project is to identify the tasks and issues involved in integrating the Content Clips templates into the broader NSDL system and incorporating content from distributed collections through collaboration with other NSDL projects and institutions with appropriate content assets. Key issues include metadata and interoperability, technology requirements, secure and easy access to distributed collections, and intellectual property rights.

Benefits Of A Template Approach For Creating On-Line Activities

While much attention has been given to search and retrieval systems for digital collections, the presentation of search results still tends to be relatively static and constrained by the limitations of HTML Web pages. Learning activity templates are dynamic environments for presenting on-line activities, acting as temporary containers to hold assets and their descriptive metadata drawn from distributed digital collections. Creating a template or learning activity interface with Flash software can add a graphical, interactive layer to digital objects. With this approach, software designers and curriculum developers could create activities with far less time and effort than in traditional software development models. By pre-selecting sets of images and creating activity templates suitable for elementary school settings, teachers can also quickly select and modify appropriate activities.

A puzzle in a game that we created for the previously mentioned Sacramento History Online Web site illustrates how objects can be dragged into a chart to categorize them (http://www.sacramentohistory.org/game_2/puzzle.html). In this on-line example, draggable graphic objects such as a chicken and a butter churn are pre-programmed or ‘hard-wired’ into the Flash movie. Such an activity could also be designed to incorporate dynamically linked digital objects from an external collection.

Benefits Of Flash As An Interface For Learning ActivitiesM

To create animations or interactive presentations for the Web, multimedia designers are turning to Macromedia (now Adobe) Flash and its free browser plug-in. We believe that this popular software can be a powerful, off-the-shelf development tool to create interactive templates that incorporate and display linked resources from digital libraries, such as images, sounds, video clips, and even other Flash animations. In a typical HTML interface, an individual object retrieved from a digital library (for example, an image of a turtle) appears on a Web page in a location pre-determined by the page designer with HTML code. Other than playing a video clip or animation, users cannot usually interact with the object or move it around on the page. Using Flash itself as an interface for presenting other digital objects opens a myriad of options for user interactions. For example, after a digitized photo of a turtle is retrieved into a template from a digital library, a student could drag and drop the turtle onto a graphic representing a marsh.

Flash includes the following capabilities that make it particularly effective as an interface for dynamically presenting objects from a digital collection within our template environment:

- incorporates built-in Flash User Interactions and calculations (check boxes, radio buttons, text input)

- parses XML generated from interactions with the Content Clips system database

- randomizes objects presented (displays a mystery object, shuffles a “deck” of Clip Cards, simulates seed dispersal)

- adds interactive layers over images and video clips (draws on or around an image, marks an image with an X or a number, masks or reveals part of an image, stacks images and clips on top of each other, and builds tools such as a magnifying glass).

- plays Flash movies within movies

The Importance Of Concept-Learning Activities

The National Science Standards emphasize that students should learn basic concepts and principles that they can build on to form broader generalizations as they pass through the grades (Erickson, 2002). To understand the concept of animal camouflage, children can practice discriminating among diverse examples and non-examples: animals that either have or lack this attribute (Lind, 1998; Miller, et al., 1996). Through digital libraries, teachers can draw on audiovisual examples of animals from all over the world. The same Flash template that presents one game for children to match video clips of mammals with drawings of their tracks can present another that lets them match photos of birds with audio clips of their calls, simply by exchanging the set of digital objects.

To support concept learning, our research team is creating templates to let children arrange, match, sort, and organize media objects from distributed digital libraries. Other templates will encourage students to explore virtual field sites and engage in activities that involve scientific observation, data gathering, and analysis.

Key Components Of The Content Clips System

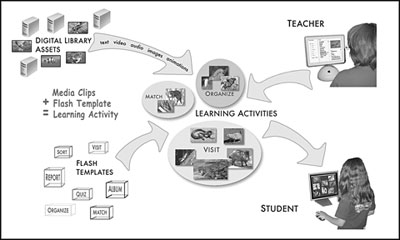

The Content Clips environment has several distinct elements, defined below. Relationships among the system components are illustrated in Figure 1.

Fig 1: Content Clips system elements and relationships

1. Clips Collection

The Clips Collection currently includes objects created by McLean Media for the targeted research. However, it can theoretically include any object on any server that allows access. Because of its agreement to adopt minimum Dublin Core metadata standards, the NSDL offers a unique opportunity to draw objects from across distributed collections. Federated content and standardized metadata tagging will allow us to incorporate objects from distributed sites.

2. Activity Builder / Chooser (ABC) (teacher administration interface)

The ABC lets teachers:

- select clips, clip sets and templates,

- assemble, customize and save activities, and

- assign activities to a class, groups, or individual students.

Clips in a MySQL database are selected through an HTML interface. Activities are presented through a Flash interface that calls to XML files. The Content Clips system will save information about individual users and user state and then determine which objects are presented and how they are displayed. For example, a teacher could choose whether the image presented in an activity displays an English or Spanish description or an alternative annotation that she has previously added.

3. Learning Activity Templates

Template types generally reflect an increase in the level of cognition required by students. Through front-end analysis with teachers, the following formats were chosen for initial study:

3.1 Album

The Album is a place for open-ended class, group, or personal collections of images, sounds, and video clips. In a group setting, such as a computer lab, an album can be a discussion tool or a way to assess children’s vocabulary and concept knowledge.

3.2 Match

With this template, children can match any two types of digital objects (e.g. image and text, image and sound, image and video) and receive positive feedback when a match is made. A graphic border or shape such as a puzzle edge may indicate how two associated objects could be connected together visually to make a match.

3.3 Sort

In a basic Sort template, images or other media objects could be sorted into columns and rows. By using relevant metadata tagging, the program will be able to check whether objects are classified correctly according to a specified criterion and then give appropriate feedback based on student responses. Objects also could be sorted into graphic “containers” rather than into columns and rows. Example: Drag all the animals that live in trees onto the forest graphic and all the water organisms onto the pond graphic. Children could match a name, photo, and clue to answer a question or riddle.

3.4 Organize

This template category includes graphic organizers for visual learning activities, such as concept maps and event sequences. In life science, activities will focus on ways to show relationships among organisms and their environments, e.g. energy pyramids, life cycle diagrams, and food webs.

3.5 Report

The Report template will provide a framework for teachers and students to create linear presentations, with the ability to place pages of text and media objects in sequential order for sharing with others.

3.6 Visit

Site visits will offer more context and opportunities for investigations. Objects might be placed within a single graphic environment and added or removed according to specific variables such as season, time of day, or the introduction of a non-native species.

4. Template-Related Tools

In addition to the template formats, we have also begun to incorporate tools into the prototype Content Clips activity environment. Tools allow users to view, manipulate, or modify clips in different ways. Some tools are template-specific, while others apply across template formats. For example, in an Album, tools might let children enlarge, rotate, or zoom into a photo. Other tools will turn metadata text visibility on or off or let teachers or students annotate a clip and save the annotation. Visit template tools may include observation, measurement, and counting devices, such as a magnifying glass or sonogram viewer. Another tool could change the season or time of day.

5. Student ClipZones (student interface)

Once activities are assembled and assigned, they will appear in student ClipZones (Flash movies), according to assignments made by a teacher or other administrator.

Preliminary Findings

Based on discussions with teachers and other educational experts on our Content Clips team, several other key conclusions have informed our design and development process. These conclusions relate to the importance of context and thematic links, an emphasis on content standards, and the value of place-based learning.

Importance Of Context And Thematic Links

Although digital collections often reflect a specific content focus, there can be a difference between content and subject matter as used in school contexts. In teaching, content is modified for different grade levels and often introduced in a pre-determined sequence, reinforced by textbooks and other instructional materials. Because teachers often need particular help in understanding how individual concepts fit into a larger picture, ideal activities provide context and promote higher levels of understanding.

Emphasis On Content Standards

It is clear that any Web-based activities aimed specifically at teachers must reflect current classroom practice. In the U.S., most science curriculum follows state and national content standards that outline a scope and sequence of instruction for each grade level. Therefore, the most obvious way to ensure a match to instructional goals is to design materials that align with these standards. In science, state and National content standards tend to be spiral in nature rather than strictly topic-based, so that concepts introduced in the lower grades are revisited at subsequent grade levels, often by adding details that scaffold new information on to prior learning.

Value Of Place-Based Learning (Regional Collections)

Many teachers rely on textbooks to provide the primary structure and content for their science instruction. Although textbook publishers pay attention to national and state science standards to ensure that their products will meet state textbook adoption requirements, many of the examples used in life science textbooks are somewhat generic or emphasize examples from states that represent the largest market share. By adopting a regional approach for selecting media clips, the Content Clips system can supplement materials already available to teachers, while still addressing content standards. For example, clip sets can be tailored by a teacher or an outside developer to feature organisms found in specific geographic locations

Results From Teacher Focus Groups

Although we have not completed prototype development and evaluation at this time, preliminary focus group discussions with 16 elementary teachers at two Northern California sites indicated that they are most likely to use on-line resources that they perceive are ‘kid-friendly,’ easy to find, appropriate for their students in terms of content and text readability, and aligned with state content standards. Our focus groups have also expressed strong interest in being able to access materials from digital libraries through an interface designed for their specific audience of learners.

Future Of The Content Clips Project

Formative evaluation in schools will continue throughout 2006. We are also looking at issues involved in collaborating with other NSDL projects to use their content within our Web environment and to allow them to use our template system on their own Web sites. Through conferences, such as Museums and the Web, we are also gathering feedback on the Content Clips prototype to guide future development for other applications. Our goal is to share our research findings and to develop the Content Clips system into a service available to NSDL projects, as well as to museums, libraries, archives, schools, and other institutions.

Acknowledgements

Support for the research project described in this paper was provided by the National Science Foundation's National Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Educational Digital Library program under grant #NSF-DUE 0435464.

References

Erickson, L. (2002). Concept-based curriculum and instruction: Teaching beyond the facts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc.,

Lind, K.K. (1998). Science in early childhood: Developing and acquiring fundamental concepts and skills, Forum on Early Childhood Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education paper, ED41877.

Miller, K., S. Steiner and C. Lawson (1996). Strategies for science learning, Science and Children, 33:6. 24-27, 61.

Varisco, Robert A. and Ward Mitchell Cates (July 2005). Survey of Web-based educational resources in selected U.S. Art Museums, First Monday, 10. http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue10_7/varisco/index.html.

Wagner, E. (2002). Steps to Creating a Content Strategy for Your Organization. eLearning Developers' Journal. eLearning Guild. http://www.elearningguild.com/pdf/2/102902MGT-H.pdf.

Cite as:

McLean, L. and R. Tessman, Increasing the Educational Impact of Digital Libraries through Learning Activity Templates, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2006 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/mclean/mclean.html