James Ockuly, The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, USA

Abstract

Many museums have recently expanded their facilities, are in the process of expanding, or are looking ahead to an upcoming expansion. What role does on-line and on site Web-based public information play before, during, and after such monumental transitions? How is the Web helping with public awareness? With capital campaigns? Are the building plans themselves accommodating needs for in-gallery media? Wired and/or wireless networking? Space dedicated to kiosks?

This paper will explore the ways in which Web sites and in-museum media can and should be thought of as another "utility" - as crucial as electricity, water, etc. - when planning for and carrying out an expansion. The primary example will be The Minneapolis Institute of Arts (MIA), but other art museums will be surveyed and discussed as well.

Keywords: building, expansion, art, branding, fundraising, planning, installation

Introduction

Fig 1: The Minneapolis Institute of Arts Michael Graves Addition, Opening June 11, 2006

In the mid- to late-1990s, a phenomenal number of American museums were dreaming of expanding their facilities. Having survived an economic downturn and attendant loss of endowment value, as well as terrorist attacks against the U.S. and the subsequent wars they precipitated, surprisingly many have gone ahead and fulfilled those dreams - or are about to.

This paper focuses on American art museums and the intersection of building expansion projects and on-line public resources. It addresses issues from early planning to public awareness and capital campaigns to the work that goes into making the eventual physical environment media rich.

While the author's direct experience is with the project now taking place at The Minneapolis Institute of Arts (MIA), a non-scientific survey in the form of phone interviews with representatives from a handful of other art museums was conducted to generate many of the ideas and materials for this article.

Public Awareness (Web Projects and Broadcast E-mail)

For most museums, the creation of a special page or section on the main Web site is the first step in on-line communication with the general public vis-à-vis expansion projects. Typical elements include a Director's statement, project renderings, information about the architect(s), Webcam images of the construction site, timelines, donation opportunities, and so forth. This may be preceded or quickly followed by notices going out in broadcast email. The MIA was no exception on this front, and produced a handsome subsection of its site that attempted to balance messages about both its building project and its capital campaign. Emails, including those designed to promote monthly Family Days began to include building project messages. As is the case with many museums, the capital campaign was designed to fund not only the building project, but also the future acquisition of art by increasing the endowment. Satisfying the public - who are assumed to be primarily interested in the building itself - as well as the institutional needs to create a clear understanding of the campaign, presented a small but significant challenge. In the end, the Web treatment balanced the various concepts (building project, art acquisition, and capital campaign) and led with a rendering of the new building and a careful and deliberate choice of verbiage on the home page, as a link to the section.

Fig 2: The MIA's Building Expansion/Capital Campaign section Home page

The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) stood out among those interviewed in that on-line public communication about their project began somewhat earlier in the process. After having selected an architect but before any serious project design had taken place, the museum arranged a series of public forums in which the architect, museum officials, and community members exchanged ideas about what the CMA renovation and expansion could be. The public was engaged and could provide feedback on-line at the earliest stages of architectural development. While the live forums were recorded and only later made available on-line, it's entirely feasible that remote audiences could actively participate in such forums as well. In another instance of listening and responding to the public, The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. (www.phillipscollection.org) targeted a very specific group for broadcast emails regarding their expansion - neighbourhood residents who were concerned with possible disruptions and had strong feelings about the project in general. The neighbours received monthly e-mail newsletters dealing with issues they themselves had raised.

Most museums use their special expansion Web sections to increase interest as the building process progresses, providing updates with some frequency leading up to the grand re-opening. A question arises, however, about the wisdom of limiting that kind of information to a discrete subsection versus integrating it more thoroughly throughout the general site - the risk being that site visitors who don't see the freestanding expansion pages are missing a significant part of the story. Usage data shows some - but not overwhelming - interest in the MIA's expansion section. It's impossible to know if many people visit regularly enough to notice updates, whether they feel updates are too infrequent, etc. Having said that, as the MIA's opening approaches, promotion of special events and other messages will indeed show up in various places on the main site - and in fact a complete redesign of the site will be launched just prior to opening, most likely solving the information ghetto difficulty.

Fig 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7: Various art museum Web treatments for special sections about building expansions

Capital Campaigns (On-line Communication and Fundraising)

Building projects and capital campaigns are more or less synonymous. And it seems that, while a fair amount of money is being raised on-line today, museums are not yet placing high expectations on the Internet for this particular purpose. There may be several reasons for this.

When dealing with prospective donors, the opportunity to engage them - and perhaps convince them to give at a higher level - has great value. If you, for example, would like to contribute to a museum, a form on a Web site can spell things out very clearly, but it can't ask you about your situation in detail and give you specifics about benefits that are suited specifically to you. It also will probably not leave you with the feeling that you've had a personal experience with someone on the inside of the institution. Anonymous interactions rob the donor and the Development professional of the chance for a more personal kind of contact. On a side note, the MIA recently added Planned Giving materials to its site. When faced with the option of allowing visitors to freely download specific information packet PDFs, or to have them request the packets via email, the Development office chose the latter - preferring the opportunity for engagement.

Another factor may have to do with just how widely the fundraising net needs to be cast. For example, the relationship between the reach of the Web and political campaign finance laws - which limit donation amounts - led to the Howard Dean phenomenon in the 2004 primaries. Large numbers of motivated people giving small amounts really adds up. But museum campaigns often stop short of going that widely public. Of course, museums tend to concentrate on their own regions rather than national audiences, and they also approach lead donors for the largest gifts first, and then fan out as necessary asking for smaller amounts. Many museum campaigns never reach John Q Public. Museums can also find themselves at what look like cross-purposes - needing to continue to meet annual goals and sell memberships while simultaneously hitting large capital campaign targets. At least for now, the revenue function of museum Web sites appears to be mainly limited to selling basic memberships, event tickets, and retail items. While a good number of museum sites are set up for open-ended donations, results are not phenomenal.

As it stands, museum Web sites and the use of broadcast e-mail are currently tilting more toward general public awareness than to direct fundraising when it comes to capital campaigns. The ideas expressed here were confirmed by many of the museums interviewed, but are by no means the final word.

Expanding - Re-Branding

Another great synonym in all of this is that between the basic process of expansion and the phenomenon of branding - or more likely re-branding. In terms of museum functions or activities, expansion projects are often on the monumental end of the scale, and the idea of transforming an institution's identity - graphic and otherwise - often coincides.

This is the case at the MIA and among most of the museums interviewed. Ranging from logo tweaks to complete rethinking of how museums relate to their communities and audiences, the concepts and trappings of branding have definitely arrived in the world of arts institutions.

Through various partnerships The Minneapolis Institute of Arts has conducted a long and thorough process, and is now implementing its repositioning plan. This involves a new look and logo designed by Milton Glaser (with the standard and worthy goal of unifying its communication materials) as well as a new approach to its audiences. The MIA's Web site redesign will appear approximately one month before the June 11 opening.

Fig 8: The MIA's current Home page (on the left) and an early mock-up incorporating the new logo and style

Understanding that there is a core group of visitors whose commitment is solid, the repositioning effort sees more attention being paid to those people who have a moderate to high interest in art, are "social" visitors, and are looking for specific amenities. It was discovered, for example, that as people move through the museum, they lose a sense of interaction because much of the front line staff is on the ground floor where there are few galleries. Several changes are taking place to make the museum more welcoming. Just to name a few, new ways of conducting tours are being developed, front line staff training is being revitalized, more seating areas are being installed, and interactive media in the form of Directories (with a built-in Art Finder) are being added, as are more Interactive Learning Stations which focus on the permanent collection.

The commitment to collecting the highest quality works of art, mounting exceptional exhibitions, and putting together the most visitor-effective programming remains unchanged, though a wider range of considerations is informing the processes behind these activities.

In discussions with other museums, many of these same themes arose. Most if not all are doing or have done at least some degree of graphic revamping - including the redesign of Web sites. In some instances, Web site re-design was actually delayed rather than instigated by building and branding projects, whose timelines required the Web re-design process to wait.

Interestingly, the High Museum did what they call "geo-branding" by altering their logo to include their physical location - Atlanta. The Web audience brings with it a need to make explicit things that may seem obvious or unnecessary. Seeing the High Museum while in Atlanta is one thing, but seeing it on the Web is quite another. Without a geographic signifier, it might take some digging to find out where in the world this place is located. So many museums have their geography built right into their names. Those that don't are now considering adjustments like the High's.

Fig 9: The High Museum's altered logo

This example opens the door to a larger question - one that originally arose in the early 1990s-- about the role of the museum in the age of global reach. What is the nature of the museum's relationship with on-line 'visitors' who only know the institution through its Web presence? It seems that cultural institutions still by and large concentrate on visiting audiences - meaning those people who are literally entering the building. But educational and curatorial-based materials especially, whether they get used in the classroom or are designed for a more general audience, can speak volumes about the quality of a museum - to people who may never see the collections in person. Online publication could be seen as a simple extension of the idea of publishing printed catalogues, though on-line art content is usually made available free of charge. In some ways, Web development is in itself a form of museum expansion.

In this intense period of transformation, it remains clear that institutional authority, authenticity, and identity are forever in conversation - sometimes debate - with the need to stay afloat financially and to appeal to large numbers of people. Questions about identity are often the most interesting and the deeper they go, the more passionately discussed. As Web-based communications develop, one of the most interesting things to participate in will be how the basic relationship between institution and audience evolves, and where the borders between outside and inside get redrawn.

Yes, We're Open/Sorry, We're Closed - In Either Case, Visit Us On-line

One of the most fundamental questions related to museum expansions is whether the existing building(s) will remain open during construction. The answers are not always as straightforward as you'd think.

In a fairly clear-cut case, the Walker Art Center (www.walkerart.org) closed its doors for a significant period of time. But their efforts to remain in the public mind paid off big time. Through a combination of a number of alternative venues for ongoing programming and an extensive graphic identity project appearing in locations throughout the city and across media platforms - including a phased redesign of their Web site - many in the community felt that the Walker's profile was actually raised during this period.

Fig 10: Walker Without Walls identity campaign as it appeared on an ice cream truck

The Seattle Art Museum (SAM - www.seattleartmuseum.org) has a more complicated transition on its hands. SAM currently consists of two buildings in separate locations. One of the buildings is undergoing expansion, the other renovation. In addition, they are constructing a new facility in a third location. The downtown location is closed due to expansion until spring of 2007, and the new facility is not yet open. In the meantime, their original building, which became the Seattle Asian Art Museum when the downtown location was first built, is temporarily hosting non-Asian art related exhibitions and events in addition to its regular Asian art programming. The film program is currently being hosted by yet another venue. All of this creates a significant communication challenge. SAM is currently conducting a single capital campaign for all of its building and renovation projects. The Web site has been partially redesigned, with an emphasis on reworking the Home page to communicate all of the changes. They also created a separate site (http://iamsamcampaign.org) dedicated to the campaign and related projects.

No two examples are completely alike. The Cleveland Museum of Art is also facing complicated phases of openness. New York's Museum of Modern Art successfully used an alternative venue - MoMA Queens - during their downtime. Thankfully, the MIA is remaining open throughout construction, and complications have been relatively minimal.

Art museums use several methods for keeping their permanent collections visible while compromised by construction. For example, it is common for works of art to be lent temporarily to other museums, and, again, Web sites are often relied upon more heavily during these times. More than one museum interviewed said that their closure helped instigate the on-line publication of objects that may not have otherwise happened, or at least not as quickly.

What has become clearer through all of this is that museum Web sites are in fact essential parts of the museum 'environment', providing information and resources, even when - perhaps especially when - the physical environment is compromised.

Public Media in the New Building(s)

Having looked at several aspects of Internet-based communications directed at remote audiences, in this section attention is shifted to the use of networked media in the museum itself.

It is almost unheard of to build a new facility without incorporating a data network. The question is, what are the intended purposes of that network? Most museums are doing a combination of wired and wireless networking and boosting the cellular reception in their existing or new buildings. In many cases, the presence of ubiquitous networking is conceived of as a benefit first to curatorial, registration, and education staff. More available network access allows working directly with collections management systems when art objects are being installed or de-installed, studied, conserved, etc. The public is being considered as well, but in many cases, secondarily. More than one museum said they felt it was important to install wireless so that visitors could at some future time access not-yet-developed programs via handheld devices. Walker Art Center provides Internet-connected computers in a lobby space, and also allows visitors to use their own devices and take advantage of a localized WiFi signal. The Walker also offers an innovative cell-phone tour - bypassing the need for visitors to rent proprietary devices.

Perhaps the most common public use of networked information in art museums is the information kiosk or other type of Web-based installation. The MIA is expanding its network of Interactive Directories from three locations to twelve. The Directory (intended for in-museum use but available at www.artsmia.org/directories/) provides practical information to visitors, including exhibition and event descriptions as well as an Art Finder, which displays the location of any object on view and points it out on an onscreen map. Visitor research showed that the number one way users thought the Directory could be improved was simply to make it more available throughout the large and now expanding museum.

Fig 11: There will be a Directory installed on each floor of the new building's atrium - some with phones that automatically connect to a staff member or volunteer

In addition, integrated Interactive Learning Stations - already a tradition at the MIA - have been designed into the gallery plans. Several new stations will be installed - each containing new programming related to the permanent collection. In one case, a Wiki-based project will complement a unique exhibition program dedicated to Minnesota artists.

Fig 12: Interactive media spaces - or Learning Stations --- of various shapes and sizes will open with the new building

Further, several small, non-networked LCD screens augmenting specific permanent collection objects and four very large digital signage displays will be integrated into the new architecture.

Fig 13: Concept rendering of large displays that will inform visitors from behind Information desks

The new generation of art museum is bringing with it many new ideas. Retrofitting media installations in hundred-year-old buildings is possible, but designing new museums makes for possibilities that would not likely be realized otherwise. The de Young Museum's new building designed by architects Herzog and De Meuron boasts a very media-rich environment, including floor to ceiling touch-screen panels that feature works of art, and a number of other media resources. Among other projects, Walker Art Center's Dialogue Table debuted at its opening in 2005 (http://newmedia.walkerart.org/dialog/). Even smaller institutions like The Phillips Collection are making sure to create networked galleries for both immediate and longer-term plans.

State-of-the-Art Presentation Spaces (and the State of Art History Presentations)

Reception halls, education centers, and lecture rooms are staples of the new art museum architecture. Outfitting these spaces with state-of-the-art gear for presentations (including single screen interfaces for controlling lights, curtains, screens, audio, and projectors) is a given, but doing so at this moment in the transition to digital materials requires that consideration be given to legacy (or soon to be legacy) technology - primarily slide projectors. It's difficult to say when slides will truly become obsolete, but in the last year or two, things have changed rapidly. Nevertheless, this longstanding art history medium is bound to linger for some time. Hybrid systems that convert slides to data on-the-fly never really took hold, so most spaces are being designed to accommodate standard slide projectors - standing alone - one way or another. At the MIA, there were aesthetic concerns in the planned lecture room. The back wall of the space, which separated it from a closet, was finished with a millwork pattern of large squares. If the closet were to be used as a projection booth for slides, a window would need to be cut from the wood panels and would seriously interrupt the aesthetic integrity of the room (a data projector hanging visibly from the ceiling in the middle of the space was perfectly acceptable for Web, PowerPoint and video presentations). In the end, two of the millwork squares were hinged and outfitted with hardware that allow them to be easily popped open, when necessary, enabling slide projector use. When not needed, the panels close seamlessly, completely hiding the window to the booth - a window whose only purpose is to accommodate slide projectors, and that is likely to have a short lifespan relative to the room.

Fig 14: The lecture room's integrity was threatened by the need to accommodate a waning medium. Architects hoped to minimize the impact of a window in the back wall

Fig 15: This solution minimized the visual disturbance of the accommodation

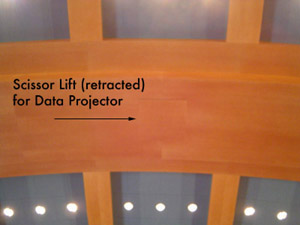

The MIA's new social space presented a similar problem. The 90-foot long reception hall with its vaulted ceiling would not easily support a data projector without compromising the architectural design. In this case, a visible data projector on the ceiling was unacceptable, so a scissor lift was installed in one of the ceiling arches, 60 feet from the screen. When not in use, the projector is retracted into the ceiling and is completely invisible.

Fig 16: The Michael Graves-designed reception hall at The Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Fig 17: The scissor lift carrying a data projector all but disappears when retracted

Another question that arose early in the MIA's plans was whether to create a high tech classroom - knowing that classes and training sessions in which each participant uses an on-line computer would be a part of its future. After much consideration, a more flexible option was chosen: a system of WiFi-enabled laptops and mobile cart with an access point that could be easily set up in any space. In addition, electronic whiteboards on rolling stands allow presenters and participants to save impromptu notes and diagrams to disc and/or to print them on the spot.

This area - the technical outfitting of presentation spaces - is where more than one museum interviewed invoked the spectre of 'value engineering.' Perhaps because plans made in flusher times now have to get through a narrower financial pipeline, visions are being adjusted. But the overall transformation taking place is remarkable nonetheless.

Afterword

Playing off of the widespread phenomenon of museum expansion, the purpose of this paper and the research that led to it is to reveal a framework of common concerns and experiences. While it has not been all-inclusive, the process of looking at issues of Web-based public information relative to major aspects of expansion projects has indeed been revealing. The interviews suggested that are probably more common issues than unique ones, but the specifics of the solutions are remarkably varied - appropriate to the various institutions' needs and abilities.

Raising these questions and making some connections may stimulate discussion among all museums that have recently completed, are in the midst of, or are looking forward to some kind of growth or expansion.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the following institutions: Cleveland Museum of Art; The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; The High Museum of Art, Atlanta; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.; The Seattle Art Museum; and Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

Cite as:

Ockuly J., Museum Expansions and the "Utility" of Web-based Public Information, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2006 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/ockuly/ockuly.html