Jemima Rellie, Tate, United Kingdom

http://www.tate.org.uk/Abstract

Over the last 10 years UK museum Web sites have come a long way. The range of content and services now offered is astonishing and inspiring. Public investment has been impressive, and on-line visits to these sites continue to exceed general trends. Ambitious digitisation projects have resulted in a wealth of assets that are regularly put to innovative use, while partnerships across organisations are stimulating an enhanced, networked culture. Of course museum Web sites continue to supply visitors with opening times, tickets and transport options, but research suggests that they are increasingly augmenting, extending and on occasion even replacing physical visits.

If such a dramatic transformation has been achieved in only 10 years, then what can we expect to happen in the next 10? Can we learn from the successes of the past decade? What challenges remain to be overcome? Which dotcom era buzz-words continue to hold promise? Do any seriously new technologies still await us? Can we afford to be complacent, or is there a danger that UK museum Web sites will fail to realise their potential? Answers to these and other questions will be presented in this paper for reflection and discussion, and in the firm belief that the best is still to come.

Keywords:Museums and the Web, UK, Internet buzz, social software, 2016

Cue

It is 2006 and the Internet buzz is back. Levels of optimism last witnessed in the late 90s are evident in all the talk of "Web 2.0", while Internet related stock prices such as Google's (http://www.google.com) are booming as they did during the dotcom bubble. UK museums on-line have seen it all before. The difference now, so we are told, is that this time the bubble will not burst.

The title of this paper deliberately refers to 'museums on-line' as opposed to "virtual museums". The distinction is somewhat forced, but it is useful to consider the distinct challenges and opportunities faced by museums whose foundations rest in bricks and mortar but who also take advantage of the Internet, and most significantly the Web, to achieve their objectives. The focus is on UK museum Web sites which have thrived over the last 10 years, not only as a result of the relentless pace of technological developments, but also due to the unique socio-political context which they operate.

The body of this paper is divided into three sections. The first section rewinds and looks back at what has already been achieved by UK museums on-line. It is not a fully-comprehensive representation of the events, but rather a selection of snapshots intended to indicate areas of interest and levels of activity. The second section pauses to reflect on the status quo: to consider what audiences UK museums on-line are currently attracting, what their editorial priorities are, and what makes them distinct. The final section fast-forwards into the future to imagine UK museums on-line 10 years on, imagining the sorts of development that will be widespread by the 20th Museums and the Web (MW) conference.

Rewind

After getting off to a bad start with the recession of 1991-92 and Black Wednesday, the UK enjoyed steady economic growth throughout the 90s and witnessed the extraordinary dotcom boom from around 1995, peaking with Lastminute’s (http://www.lastminute.com) initial public offering (IPO) in March 2000. Museums, like other sectors, were encouraged by this boom and looked for ways to both invest in and profit from the Internet. The earliest adopters of the Internet within the UK museum sector were, perhaps not surprisingly, organisations with strong research and academic links.

The Natural History Museum (NHM, https://www.nhm.ac.uk) was the first museum to launch in 1994, shortly followed by the Science Museum (http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk), both benefiting from the close physical co-location with Imperial College and its high-speed academic JANET network (see Table 2: Dates when a selection of UK museums first launched their Web sites). Another museum quick off the mark was a university museum: the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, which launched in 1995. As is clear from the initial URL (http://www.gla.ac.uk/Museum/), the Hunterian site was, from the outset, a collaborative effort between the museum staff and the Department of Computing Science at the University of Glasgow, who began work in October 1994. Jim Devine, then the Education Officer and now the Head of Multimedia at the Hunterian, recently described the first version of the site as consisting primarily of “fairly straightforward content with still images and text” (E-mail conversation, January 2006). However, to its credit he did also suggest that even at this early stage staff spent a lot of time optimising the navigation and attempted to deliver a virtual tour using still images and hotspots.

| Year | Site |

|---|---|

| 1994 | Natural History Museum (http://www.nhm.ac.uk) Science Museum (http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk) |

| 1995 | Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery (http://www.hunterian.gla.ac.uk) |

| 1996 | The Victoria and Albert Museum(http://www.vam.ac.uk) National Museums and Galleries of Wales (http://www.nmgw.ac.uk) |

| 1997 | National Maritime Museum (http://www.nmm.ac.uk) Guernsey Museums and Galleries (http://www.museum.guernsey.net) British Museum (http://www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk) |

| 1998 | Tate Online (http://www.tate.org.uk) National Gallery (http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk) Imperial War Museum (http://www.iwm.org.uk) East Lothian Museums (http://www.eastlothianmuseums.org.uk) |

| 1999 | 24 Hour Museum (http://www.24hourmuseum.org.uk) National Galleries of Scotland (http://www.natgalscot.ac.uk) |

Table 1: Launch dates of key UK Museum Web sites

| Year | Site |

|---|---|

| 1994 | Yahoo (www.yahoo.com) |

| 1995 | Amazon (http://www.amazon.com) eBay (http://www.ebay.com) Craigslist (http://www.craigslist.org) Alta Vista (http://www.altavista.com) |

| 1998 | Google ( http://www.google.com) Last Minute (http://www.lastminute.com) |

| 1999 | Napster (http://www.napster.com) Blogger ( http://www.blogger.com) |

| 2001 | Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org) |

| 2002 | Technorati (http://www.technorati.com) |

| 2003 | del.icio.us (http://del.icio.us) |

| 2004 | Flickr ( http://www.flickr.com) |

Table 2: Significant sites in the development of the Web

Little budget was allocated to information technology (IT) in most pure-play UK museums in the early days of the Web, let alone to on-line development. This meant that many first museum Web sites were reliant on the enthusiasm and talent of individuals such as David Saywell, then the Information Technology (IT) Co-coordinator and now Head of Information Technology at the National Portrait Gallery. David recalls how he ''set up the Gallery's first Web site from scratch using Adobe PageMill in August 1996, about 5 months after I set up Gallery-wide access to e-mail for whoever wanted it.'' (E-mail conversation, January 2006) The whole site fitted on a floppy disk - David remembers because he had to take the contents over to the Internet service provider (ISP) personally as the file transfer protocol (FTP) was playing up.

The following year, in March 1997, the first ever MW conference was held in Los Angeles, USA (http://www.archimuse.com/mw97/). This was the year that Dolly the sheep was cloned; that Channel 5, the UK's 5th terrestrial television station started broadcasting; that Tony Blair was appointed Prime Minister; and that Princess Diana died in a car crash (Wikipedia, 1997). The Netscape initial public offering (IPO) had taken place 19 months earlier; the speculative Web land-grab was well underway; and Amazon served its one millionth customer (Bezos, 2005). Ten years ago, in 1997, the term “cyberspace” was still in fashion and, hard as it is to believe, the Internet was considered a “raucous and untamed territory” (Fink, 1997).

Several UK museums Web sites were up and running by 1997. While the impetus for the very first sites was research and academia, enthusiasm quickly spread and other motivations soon followed. Soon, UK museums started to embrace the Internet as a useful channel for information, and as a complement to their print based marketing activities. Indeed the primary goal for many early museum Web sites was to promote off-line activities by providing listings-based content on events staged at the physical galleries, along with visiting information and directions. This objective proved relatively easy to meet, and, encouraged by both technical developments and Internet hype, many soon adopted two new and far more ambitious objectives: to increase virtual access to the collection and programmes and to increase revenues through e-commerce. Once the Tate Web site launched relatively late in early 1998, it not only offered listings information but also contained a partially illustrated concise catalogue of a few thousand collection highlights, on-line feedback forums, an opportunity to 'chat' about the Turner Prize, and a selection of own-brand material products for purchase, including books, gifts, posters and postcards (http://www.tate.org.uk).

Great progress was made within the UK museum sector on-line in this first decade of the Web, but it was not entirely smooth sailing. Encouraged by the boom years, risks were taken, some of which proved subsequently to have been unwise. The feared Y2K (year 2000) bug proved to be harmless, but soon after its arrival the dotcom bubble burst and counted UK museums on-line among its victims. Tate, for instance, entered into a joint venture with MoMA in 2000, to develop a site called Muse which sensibly never actually launched. But while the burst bubble curtailed some short-term ambitions, continued development across the sector made it clear that that few doubted the long-term benefits the Internet offered.

Despite the widely shared belief in the power of the Internet to help UK museums fulfil their remits, UK museums have yet to receive core government grant-in-aid dedicated to support their on-line manifestations. Instead, government funding has been made available for on-line developments through a series of project-based funding schemes. One significant source of financial support was the National Lottery which had been set up in 1993 to support good causes in the arts, heritage, health, education, environment, community and charity sectors. Tate alone secured a total of approximately £1 million from two lottery distributors (Heritage Lottery Fund, http://www.hlf.org.uk and New Opportunities Fund, http://www.nof.org.uk), enabling us between 1998-2002 to digitise and provide on-line access to the entire collection of over 65,000 works. Another example of financial support for museums on-line has come directly from the Treasury in the form of the Invest to Save scheme (http://www.isb.gov.uk) which, for instance, enabled the Science Museum to launch its award winning £1 million site Making the Modern World in 2004 (http://www.makingthemodernworld.org.uk/). Support from The Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) came in Culture Online, a commissioning and production unit with an initial £13 million budget, established in 2002 (http://www.cultureonline.gov.uk) and responsible for initiatives such as the £1 million Victoria and Albert (V&A) museum-led site Every Object Tells a Story, launched in 2005 (http://www.everyobject.net). From the outset these funding opportunities all encouraged innovation. More recently there has also been an emphasis on collaboration among museums and partnership across sectors. It is possible to argue that insufficient government spending has been allocated to UK museums to develop their on-line presences, but it would be wrong not to acknowledge how beneficial these funding programmes have been to the museum sector.

The UK government has helped lead the way for museums on-line with its digital funding support, just as UK museums are at the cutting edge of programming, both off- and on-line. While collecting remains a core function of UK museums, many are now as interested in the visitors they welcome as the objects they collect. Increasingly UK museums are valued by UK society not only as centres of preservation, but also as social spaces for cultural exchange and platforms for debate. Developments in digital technologies have to date acted both as catalysts for these changes and as supports. As the Internet has become faster and more ubiquitous, and the time spent on-line by the UK population has increased, so UK museums have continued to evolve and take advantage of new technologies in ever more radical ways.

Play

In 2006, the pace of technological development shows no sign of slowing down. The sheer scale of activity amongst UK museums on-line today is difficult to represent, not least because of the range and diversity of museums in this country. The UK population reached 60 million in 2004 (National Statistics, August 2005); it is estimated that there are currently as many as 3000 UK museums (Museums Association, 2005). A survey across all these organisations is particularly tricky as they are funded in different ways and no central, complete listing exists. Anecdotally, however, it is possible to suggest that the vast majority of UK museums do now have some level of on-line presence, and this is certainly the case with the national museums (National Museums Directors' Conference, 2005). It remains challenging, however, even to map the activities of the national museums on-line, as there is little consistency either in the way they structure their internal resources or in the shape of their public on-line offerings.

Usually, those responsible for the development of a UK museum’s Web site in-house are based primarily within the IT division (e.g. The Science Museum), the communications division (e.g. The National Gallery), or the education division (e.g. The V&A); sometimes the core staff are spread more evenly across a combination of all three (e.g. The British Museum). Few UK museums have yet to fully embrace and promote the "museum" top level domain (TLD) and stick, more often than not, with either .org.uk or .ac.uk. Many museums have changed their URLs since launching (e.g. http://www.elothian-museums.demon.co.uk became http://www.eastlothianmuseums.org), and several continue to use more than one address for different functions or topics (e.g. the British Museum: http://www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk, http://www.britishmuseum.co.uk, http://www.ancientgreece.co.uk, http://www.mesopotamia.co.uk, etc). To complicate matters even more, a number of museums are engaged in partnership on-line projects which manifest themselves in yet more sites (e.g. http://www.everyobject.net), while many of the smaller museums pool their resources in one site (e.g. Tyne and Wear Museums: http://www.twmuseums.org.uk). Evaluating this web of activity as a whole is made more problematic by inconsistent methods of log file analysis - an issue which continues of course to confound the wider Internet community.

Despite this diverse and complex state of play, it is possible to identify some clear trends that have emerged since UK museums moved on-line. The two primary functions for UK museums on-line in 2006 can be put simplistically as

- increasing audiences and

- improving access

The importance of these roles for national UK museums on-line is in part reflected by the figures requested by the DCMS as part of their funding agreement. Each year all national museums submit two figures to the DCMS in relation to their on-line audiences: the total number of visitors on-line and the percentage of the collection digitised. More often than not it is the marketing and education teams within museums who still make best use of the Web sites, although excellent examples abound of other groups now contributing to their success. Indeed it is not now uncommon for all museum functions to be represented in their Web presence and for all museums departments to use on-line as a cost-effective method of disseminating information, communicating with visitors and remaining transparent

The audience for the general visitor-focused content is frequently broken down into three groups:

- those preparing for a visit,

- those extending a visit

- those visiting the Web site as a destination in its own right.

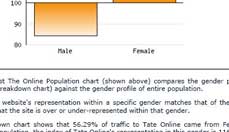

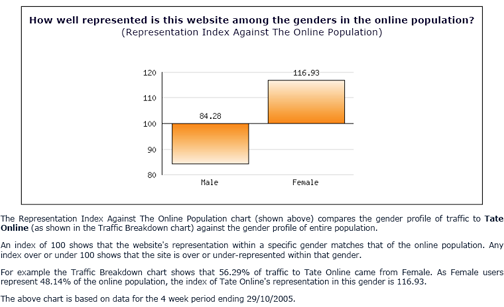

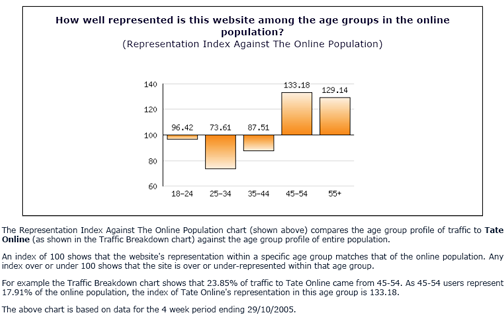

Content is increasingly created to target each of these groups differently, be it through offering downloadable podcasts, conducting on-line chats with curators, or Web-casting live events. Rigorous research into the audience share for these three categories remains lacking, but there is anecdotal consensus among London museums on-line that this audience is split evenly, with 1/3 visiting the off-line gallery pages, another 1/3 visiting the on-line collection, and the final 1/3 split across other areas such as e-learning and the shop (London Museums On-line Group discussion, October 2005). There is also evidence from Hitwise (www.hitwise.co.uk), that UK museums on-line consistently attract more women on-line than men (see Table 3a: Tate Online traffic share by gender, Hitwise, 2005) , that the audience is quite evenly spread across the age groups (suggesting an above average share of older surfers) (see Table 3b: Tate Online traffic share by age, Hitwise, 2005) and that the biggest clusters of visitors are local to the physical sites (see Table 3c: Tate Online traffic share by location, Hitwise, 2005). More research into these demographics is desperately needed to test these apparent patterns and understand better the motivations for on-line visits and what opportunities still exist to support them.

Table 3a: Tate Online traffic share by gender

Table 3b: Tate Online traffic share by age

Table 3c: Tate Online traffic share by location

For some time now, in-house log file analysis has suggested that on-line visitors to UK museums have outstripped the number of off-line visitors. Tate Online, for instance, now attracts more visitors on-line than to the four off-line galleries (Tate Modern, Britain, Liverpool and St Ives) combined, attracting 7,722,928 unique visitors in 2005 (Tate Webtrends, 2005). This figure is slightly disingenuous, of course, since the same log file analysis also suggests that on-line visits remain far shorter (averaging just over 10 minutes) than off-line visits (averaging just under 2 hours), but calculations of the cost per minute per visit do support the view that on-line museums offer good value for money. The ongoing maintenance for most UK museum Web sites comes from existing core funding, i.e. at the expense of other existing activities, while museums continue to rely heavily on project based public-sector grants for significant developments. European funding opportunities are beginning to be explored (e.g. eContentplus), resulting in new cross-EU partnerships and proposals. Surprisingly few UK museums on-line are sponsored in any significant way (BT's support for Tate Online being an exception to the rule), despite the value of off-line commercial support, although on-line will frequently piggy-back on off-line relationships; for instance, to deliver sponsored exhibition microsites.

The vast majority of content at UK museums on-line remains free to all, although most sites do offer some form of e-commerce activity, now often in the form of ticket and membership sales, as well as standard on-line shops and increasing opportunities to customise goods for purchase (e.g. The National Gallery's Create Your Own series of cards, calendar and prints: http://www.nationalgallery.co.uk/shop/CreateYourOwn). Informal research suggests that while tickets, memberships and customisable products sell well, UK museums still struggle to make any significant profit from their traditional shops, on-line. There are several reasons this is the case, including the fact that the product range offered is often less extensive than off-line, there is usually little systems integration with other areas of the site, and perhaps most significantly, the products are frequently available elsewhere on-line for less.

Above and beyond competition for e-commerce, UK museums now face competition on a variety of other fronts, including on-line audiences and content. This competition is no longer restricted to other sites within the museum sector. UK museums must increasingly compete over content and audiences with libraries, archives, broadcasters and newspaper publishers. As traditional distinctions between these organisations continue to blur in the digital age, so too does their output on-line. This is as true for say the NHM in terms of the BBC’s Science and Nature content on dinosaurs (http://www.bbc.co.uk/sn/prehistoric_life/) as it is for Tate in light of the Guardian's on-line coverage of the Turner Prize (http://www.guardian.co.uk/arts/turnerprize2005/). Ultimately all these organisations are content organisations, and as more content is born digital, the playing field will continue to be levelled. This state of play is reflected quite clearly in the recent EU Commission’s i2010 communication on digital libraries (http://europa.eu.int/information_society/activities/digital_libraries/index_en.htm).

In 2006 the dotcom mantra that "content is king" still rings true, and UK museums must continue to capitalise on their content and offer it in new ways to larger audiences. But this alone is unlikely to be enough to ensure that museums remain relevant in the future. Rather it seems likely that a more profound change is still underway and will require museums to re-define their objectives and their structures. This is necessary because, to quote Erkki Hutamo,

With images and sounds reproduced in principle in unlimited numbers, and distributed, copied, mixed and manipulated at will by the media, the idea of temples dedicated to the cult of the authentic (or “auratic”) objects seem(s) outdated to many. (Hutamo, 2002)

If UK museums are to retain their social status, then they must re-assess their role in contemporary society and change, still further, with the times.

Fast Forward

UK museums in 2016 will be different from the organisation we know today, and the impetus for transformation will remain technological developments. Those that continue to embrace change and integrate digital programmes into the heart of their organisations look likely to extend their role, influence and value in society as the Internet allows them to engage new and bigger audiences, directly and over time. This evolution is unlikely, however, to be imposed on museums, and history suggests that some will remain rooted to old models and stagnate. For although UK museums have now embraced the Web to some extent, it is possible to argue that they have failed as yet to embrace it as wholeheartedly as they should.

When compared with other sectors, UK museums were not particularly quick to get on-line, and they have not been fast subsequently to redirect resources to support their on-line developments. At first this might have proved prudent, not least as the technology on offer quite simply did not live up to the hype. But most of the buzzwords of the 90s are now increasingly a reality, including most significantly broadband, convergence and ubiquitous computing. As a result, rather than waiting for the technology to catch up, UK museums are now increasingly in danger of failing to capitalise on the opportunities that exist. If the trends we have witnessed in society in general as a result of the Web continue to pick up pace, then UK museums are in danger of being will left behind and failing to fulfil their potential. Examples of the real danger posed can be seen in other sectors that chose not to prioritise on-line integration, including most infamously the music and publishing industries. In order to avoid the same fate as these industries, it is crucial that museums be at the forefront of cultural developments on-line.

Museums must start to think digital in everything they do. This does not mean they must stop collecting objects or curating physical exhibitions and funding their bricks and mortar platforms. Indeed quite the opposite, as these are activities which make museums distinct in the digital age, giving them their purpose and edge. Rather, museums must adopt a hybrid approach to collecting and programming to ensure that all the skill and effort that goes into securing and cataloguing a new acquisition, or curating a display or event off-line, is amplified on-line. This need not be a laborious or expensive exercise. As long as the requirements are carefully thought through in advance, and suitable processes and training are offered to staff, then the financial impact will be minimal and a return on investment will be easily met.

The working assumption should be that all public content created within the organisation should be destined for on-line distribution as well as put to any other intended use. UK museums own the intellectual property (IP) of content created by their staff and should flex this right fairly to the benefit of tax payers, the organisation and the individuals involved. If a member of the photography team captures a display, then it should be documented digitally and an edited selection should be made available on-line. If a member of the education team invites artists or scientists in to discuss their work with the public, then these discussions should be recorded digitally and offered on-line. If a collection curator contributes an article to an external journal, then this article should also appear on the author’s museum Web site. If a book is published, then this content should be offered on-line simultaneously. If a broadcaster is given free access to film an exhibition, then a copy of this footage must be made available to the museum to use on-line. Museums are now in the business of collecting not just objects, but also digital content. Amazon’s experience demonstrates that if all this content is aggregated and delivered on-line it will constitute a valuable long-tail (Anderson, 2004).

Above and beyond satisfying a public demand for content, an added benefit of this approach is that the museum will be archiving its evolution in a highly accessible way. Culture is not a fixed entity. Cultural values change over time and vary across space. If we accept that culture plays an important role in defining identity, then it is also true that analysing culture over time will help us and others to understand how we got to where we are today. Museums have long played an important role in presenting and preserving the culture of the UK, and the opportunity to explore past programmes and interpretations would open up an extraordinary resource to historians. For this reason, museums should archive as much digital content on-line as possible, irrelevant of whether it is "timely". This includes listings information, for instance, because these ephemeral events programmes can tell historians a lot about what the museum and by extension society valued at any time. Once published on-line, archiving this content is not onerous. The storage costs are negligible and as long as the content is clearly dated, if not deemed relevant it can be easily ignored.

Four major hurdles do however exist and will need to be overcome to secure public access to this potentially rich archive in 2016. The first is the challenge digital content offers in terms of preservation. Many UK museums are concerned about digital preservation, but few have yet established policies for it, and currently only time will tell what impact this will have and how much more content will be lost in the next 10 years. To safeguard their futures and our histories, museums should adopt a leading role in the research into digital preservation, much as they have traditionally led research into the conservation of objects in their care. Currently, in the UK, security, archiving and back up policies are established and maintained by IT departments. To ensure they are fit for purpose it is essential that they be understood and reviewed by a wider museum community with complementary concerns and interests, and signed off at Director level.

The second difficulty that museums will have to tackle is copyright. Copyright law in the UK is not well suited to the digital age: securing and tracking multi-media licenses is complicated, costly and time-consuming. Enormous effort can go into creating an on-line resource, only to need to destroy it once the copyright on certain elements expires. This runs contrary to UK museums' objectives to conserve culture and increase access to it. As a starting point museums should review all their contracts and amend them where possible and fair to include on-line non-commercial use, in-perpetuity. Museums must also do more to engage directly in the debates around copyright, sign up to the Adelphi Charter (http://www.adelphicharter.org.uk) and explore the use of alternative models, including Creative Commons licenses (http://www.creativecommons.org.uk). This is becoming an increasingly urgent matter as the Internet becomes more commercialised and notions of the public domain are further threatened and eroded . A core function of museums, to store culture for the experience of future generations, is under threat, and UK museums' must work together and lobby for a solution. Free access to national collections is something UK museums will have to defend on-line as well as off. Free access to UK museums on-line is in no way guaranteed in 2016.

Assuming UK museums on-line do manage to preserve their collections of digital content and maintain free access in 2016, then the third hurdle the public will face will be finding what they want. Finding what you want on-line can be a challenge even now, and this problem will be exacerbated as the amount of content increases. Museums" Web sites have the potential to cater to a vast range of visitors who may or may not know what it is they are looking for. If visitors cannot find what they are looking for, the sites might as well not exist. The vast majority of on-line content is not accessible directly from a museum homepage but rather is buried deep within an ever-expanding directory hierarchy. To ensure easy future retrieval of digital content, it is essential not only that best practice is followed in terms of information architecture, fixed URLs and naming conventions, but also that efforts are made both to optimise content for search engines, and to develop new in-house tools to complement these search engines and make up for their weaknesses.

The successful museums of the future will deploy many of the tools associated with Web 2 (O'Reilly, 2005) to help visitors retrieve and share content of interest. Use of "really simple syndication" (RSS), for instance, will be widespread among museums, used to deliver, or "push" relevant content out of sites and into communities of interest. Simple to set up and maintain, RSS allows museums to disseminate any range and combination of feeds to suit visitor demands. A key benefit of RSS is that it takes the onus off the visitor to check for updates, but rather alerts them to new content as soon as it is available. The technology has been widely adopted by the newspaper community, and is increasingly being taken advantage of by UK museums too, such as the 24 Hour Museum (http://www.24hourmuseum.org.uk) to deliver listings information and podcasts. Although RSS encapsulates a reasonably simple concept, when put to good use it offers a very powerful way to keep in regular, close contact with visitors.

Some of the more revolutionary Web 2 tools waiting to be used by UK museums can be grouped under the umbrella term "social software" (Shirky, 2003). By aiding social interactions and facilitating as yet unfamiliar forms of many-to-many interaction, social software will further challenge traditional museum power structures and spheres of influence. Although software for group communication has been around for some time, it’s only now that there has been a surge of interest in many-to-many interaction. Not much effort has yet been made in this direction within the museums community as the focus to date has largely been on creating digital assets and publishing existing expert knowledge. The two social software formats of particular interest to museums are social tagging and wikis. By 2016, these formats will be thoroughly familiar and well integrated into the leading UK museums on-line.

Social tagging allows users to annotate or "tag" content, created either by themselves or by others. So far it has attracted the most high-profile interest from Yahoo, with its recent acquisitions of Flickr (http://www.flickr.com) and del.icio.us (http://www.del.icio.us, Johnson, 2005). Yahoo believes that social tagging will form the basis of the next generation of search engines. As the extent of content on-line continues to grow, Yahoo believes that we will all look to our friends and communities of interest to filter relevant information for us. Social tagging will result in museum content resonating with ever larger audiences by allowing visitors to interact with it in fragmented, non-prescriptive ways. Folksonomies will emerge to complement traditional expert taxonomies, opening up access to collections related information still further. A few museums, including the US-based "steve" consortium (http://steve.museum), are just beginning to explore social tagging applications, but we can expect a massive growth in usage over the coming years.

Wikis are sites that allow users to edit their content or make additions. The most celebrated wiki to date is Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.org): a multilingual, open-access encyclopaedia on the Internet. Museums have yet to adopt wiki formats on-line, largely due to the threat they present, similar to social tagging, by suggesting the general public might be capable of contributing, in an interesting and meaningful way, to collection related content. But the situation is changing, and user generated content (UGC) is already making its way into institutions, albeit largely in self-contained, fringe ways such as visitor authored audio-tours. This is a trend that is certain to continue, and it seems likely that in the near future museums will adopt wiki formats not only to encourage engagement through participation, but also to fill in gaps in the museum's information. Whilst there is scope to increase both the type and the depth of expert knowledge available at museums on-line, limited resources will never match the opportunities available. Wiki interfaces should be used to counter this limitation and enable visitors, including interdisciplinary professionals, to enhance content and share alternative perspectives.

In addition to soliciting help from their visitors to succeed, museums on-line will improve over time if they adopt simple policies that actively support each other’s efforts. One way, for instance, that UK museums could raise the profile of their content is simply by agreeing on a proactive reciprocal linking policy to promote each others' offerings. Museums are amongst the leading authorities on the subject areas covered by their collections, but due to finite resources and international demand, they will seldom be the sole repository for the sorts of objects they collect. Traditional collection boundaries are easily surpassed on-line, and museums must do more to take advantage of this and assert their combined authority through co-promotion. This would benefit not only the museums who participate in any such scheme but also the public. For the first time the public would have an unbiased and trustworthy view of authoritative content across the range of subjects covered by the museum sector.

Professional collaborative working should extend beyond an agreed and mutually beneficial links policy to more supportive arrangements for image usage. Quid pro quo agreements should be established which allow museums to use each others' images on-line, cutting out bureaucracy, saving time and money, and further encouraging a sense of community. Where possible and appropriate, these policies should be implemented beyond the UK to extend the benefits internationally. What such policies would demonstrate is that while museums individually might have limited influence, together they combine to be a significant force.

Conclusion

UK museums overall offer a wealth of content that spans the UK curriculum and represents identities and interests of the British population. As predicted, digital technologies have provided museums with an unprecedented opportunity to deliver further rich programming directly to visitors at a time and place that suits them. Broadcasters no longer control the networks to distribute audio-visual content: a high-end digital camera can be bought for a couple of thousand pounds. As we approach the digital switchover in 2012, UK museums must take greater advantage of these facts to provide the public with an increased choice of free content available on-demand. The benefits to museums of creating more rich-media content are manifold: expertise is harnessed, resources are shared, quality is assured, and licenses are made more manageable. This argument is gaining ground, and if UK museums consolidate it, then it is entirely possible that by 2016 they could receive further public financial support in the form of something similar to Ofcom’s proposal for a Public Service Publisher (PSP, Ofcom, 2005).

Digital technologies subsume all previous mass-media, including books, radio and television, and lower the barriers to production and distribution of these forms (van Koten, 2005). Just as radio did not kill books, nor television radio, it is safe to assume that the Internet will not kill any of them either - at least, not by 2016! Instead what we will soon see happen is digital technologies become the primary means of distributing and accessing texts, audio and film for all content creators, including museums that thrive and survive. It is also clear that digital media do far more than offer efficient and easier ways to experience older media. 'New media' also offer complex new ways to layer and relate 'old media', as well as an opportunity to develop new environments within which to enjoy them. Representational, 3d virtual worlds are one form of cultural experience that continues to hold promise for museums. These 3d environments are hugely successful when used for historical re-creations, battle training and game playing, but museum use in the UK has so far been limited to academic research, such as the work undertaken by the University of Glasgow in collaboration with Lighthouse Centre (Galani and Chalmers, 2002). Internet technologies now support cheap, real-time global communication, and by 2016 it is likely that we will experience photorealistic immersive environments. Museums will have as valid a role to play in these virtual environments as they do in the UK today.

Arguably the vision and ambition for UK museums on-line has not changed fundamentally in the last ten years, but rather technology and public appreciation are finally catching up. The hype of the late 90s is becoming a reality, and the Internet is proving to be one of the greatest technology inventions of all time. From the outset UK museums recognised the potential of the Web to support and enhance their objectives, and the papers included in this year’s MW conference confirm that the passion and enthusiasm continue to thrive. Digital technologies are still simultaneously supporting and transforming UK museums, and if all goes well, then the single most significant development in 10 years" time will boil down quite simply to an increase in visitor choice. By 2016, UK museums on-line will offer a wider choice of content, to more diverse audiences, in a format and context that suits each individual visitor best.

References

Anderson, Chris. The Long Tail. Wired. October 2004, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/12.10/tail.html.

BBC. Renewing the BBC for a Digital World. June 2004. http://www.bbc.co.uk/thefuture/pdfs/bbc_bpv.pdf, consulted January 2006.

Bezos, Jeff. Interviewed by Jeff Howe, 1997. What They Were Thinking Wired, August 2005. http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/13.08/1997.html, consulted January 2006.

Fink, Eleanor. Keynote Address: Museums and the Web 1997. http://www.archimuse.com/mw97/speak/fink.htm, consulted January 2006.

Galani, Areti and Matthew Chalmers. Can You See Me? Exploring Co-Visiting Between Physical and Virtual Visitors, 2002. Museums and the Web, http://www.archimuse.com/mw2002/papers/galani/galani.html, consulted January 2006.

Hitwise Report. Lifestyle and Demographics Report for Tate Online, October 2005.

Hutamo, Erkki. On the Origins of the Virtual Museum. Nobel Symposium: Virtual Museums and Public Understanding of Science and Culture, May 2002. http://nobelprize.org/nobel/nobel-foundation/symposia/interdisciplinary/ns120/lectures/huhtamo.pdf, consulted January 2006.

Johnson, Bobbie. Searching for a Fresher Taste. The Guardian, December 15 2005, http://technology.guardian.co.uk/weekly/story/0,16376,1667276,00.html, consulted January 2006.

Museums Association. FAQs, 2005. http://www.museumsassociation.org/faq, consulted January 2006.

National Museums Directors' Conference, Members 2005. http://www.nationalmuseums.org.uk/members.html, consulted January 2006.

National Statistics. Population Estimates, August 2005. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/CCI/nugget.asp?ID=6, consulted January 2006.

Ofcom. Review of Public Service Television Broadcasting, Phase 3: Competition for Quality, February-March 2005. http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/psb3/, consulted January 2006.

O'Reilly, Tim. What Is Web 2.0, Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software, 20 September 2005. http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20.html, consulted January 2006.

Shirky, Clay. Social Software and the Politics of Groups. First published March 9, 2003 on the "Networks, Economics, and Culture" mailing list, http://shirky.com/writings/group_politics.html, consulted January 2006.

Tate Online. Webtrends Reports, January - December 2005, generated in-house.

van Koten, Hamid. The Digital Image and the Pleasure Principle: The Consumption of Realism in the Age of Simulation. CHArt Twenty-First Annual Conference, November 2005.

Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1997, consulted January 2006.

Cite as:

Rellie J., 10 Years On: Hopes, Fears, Predictions and Gambles for UK Museums On-line, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2006 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/rellie/rellie.1.html