![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

When is the next

Museums and the Web?

![]()

Archives &

Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto, Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

info@ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search

A&MI |

Join

our Mailing List.

Privacy.

Copyright

Archives & Museum Informatics

2000

Cooperative Visits

for Museum WWW Sites a Year Later:

Evaluating the Effect

Abstract

Webtalk-I is a powerful tool that allows creating Virtual Reality three-dimensional worlds, in which people can meet, by means of an Internet connection. Each one of the virtual visitors can remotely explore the Virtual world. In addition a virtual visitor can examine and interact with components of the world. Like in a real world situation, a visitor can see where the other visitors are currently located, where they are going, and what they are doing. Visitors exchange opinions or information with other visitors, using the keyboard. Visitors can interact with 3D objects, sharing the experience of the interaction with other visitors. An experimental application of Webtalk-I was presented last year during the closing plenary of MW99. It consisted of a reconstruction of a virtual museum, based on the Milan Science Museum, in which visitors could operate Leonardo's machines.

After extensive testing, the environment, called "Virtual Leonardo" was officially opened to the public on June 7, 1999, in an extended and debugged version. We tried also some experimental virtual guided tours (one during ICHIM 99), with interesting results in educational terms. In this paper we evaluate the results of the first 6 months: how many visitors we had, what they did, the problems they had, the suggestions they gave us. Based on this experience is the design of the new WebTalk-II platform, currently under development.

Cooperating in Virtual Spaces

The great part of museum web sites offer navigation paths called "virtual tours". In the simplest cases, these tours are in reality a collection of web pages, organized in a logical sequence, which offer a sort of guide to the museum. To exploit more fully the possibilities of multimedia technologies via the internet, another common approach is to provide 3D environments which the cyber-visitor can navigate freely. These environments are very often QuickTime VR shoots which can be viewed with a standard plug-in. While this approach can convey a minimal feeling of 'being there', several questions arise on this approach. First of all, the task of guiding the visitor is left to the content of the web page itself. Moreover, the visitor has no notion of other visitors which may be more experienced and with which he could exchange ideas or comments, quite a common scenario during a visit to a real museum. Secondly, not always mimicking the reality of the museum is the winning choice in presenting the museum contents. One can exploit the freedom from the chains of physical reality, and represent in electronically recreated worlds what would be nice to see in the real museum, but the constraints of physics prevent to do.

Supporting cooperation between users during web browsing is not such a new idea anymore. Several players in the Internet arena have by now realized that surfing web sites is one of the few activities that is still experienced alone. The net offers a number of chat-boxes and virtual communities which are more or less unrelated to an underlying web site (Active Worlds, http://www.activeworlds.com; Blaxxun Colony City, http://www.colonycity.com/index.html; Ultima Online, http://www.owo.com ). This approach often lacks a real referencing system to already existing web contents with a complex structure. We have thus a good 3D cooperation system, but a weak link to any existing web site.

Recently it is possible to see efforts to support cooperation between users visiting the same web site, or even the same web page. These approaches usually get to the user via NetMeeting (allowing audio and video links with a pre-arranged rendezvous on a given server), or use special plug-ins to integrate into the web site the typical chat functionalities and cooperation patterns of cyber communities. There is still a lot of 'bidimensional thinking' in these solutions, and as a consequence, cooperation is clumsy and indirect. It is only the learned familiarity of the users with the list-of-users and colors-of-different-meanings metaphors that make the system work (Hypernix Gooey, http://www.gooey.com ). Here we have a fairly tight link to web contents, but a poor cooperation system (or at least less imaginative than it should be), cast in a 2D frame.

We are convinced that an interesting solution will combine 3D Virtual Communities techniques with 2D web site structures. Collaboration is supported within the museum environment by any 3D representation, augmented with a 3D access structure to the museum's web site contents. This is the underlying philosophy of the WebTalk-I and WebTalk-II projects at Politecnico di Milano.

With WebTalk-I, you can draw the museum environment in 3D, and decide the position of the exhibits inside it. You can specify for every object the actions that may be performed on it (click it, drag it, rotate it, light it, hit it). You can also decide if the effects of these actions are to be seen only by the actor, or you can make them shared, that is the effects are seen by all the people which are navigating the museum space in that same moment. You then define the links that allow to jump from the 3D space to the related 2D web page. For example, clicking on an info billboard next to a huge 3D mechanical clock, pops up the web site page related to the clock. While you walk in the 3D museum, you see all the others in the form of avatars, little human figures. This way it is very easy to see at a glance how many people are viewing the same information (space) you are, and what each user is doing in every single moment. This is because 3D is the metaphor we use everyday to cooperate in real life.

3D spaces allow to use a whole different set of rules for cooperation. An immediate advantage is the possibility to create 'special users' which can function as guides or clerk assistants, and guide other users (in groups or one by one) to the visit of the site. These guides can be driven by humans, can be automated agents with artificial intelligence, or can be robots which follow pre-recorded tours.

Technically speaking, WebTalk-I uses the VRML97 language to represent the 3D shapes, and the Java language for the communication engine with other users. These are two internet standards, so users should not have problems installing the necessary software to experience the virtual collaborative museum.

Our first goal was to apply these ideas to a real museum, creating a suitable 3D environment. We approached a museum with an existing website, to cooperate and with sufficient exposure. This is how Virtual Leonardo started its days on the web.

Virtual Leonardo: evaluating effects and reactions

You can enter Virtual Leonardo from the main page of the National Science Museum in Milan (http://www.museoscienza.org). The environment represents rather faithfully the inside of the cloister of the monastery which houses the museum. From the cloister you can enter different rooms, and each room contains a 3D version of a machine inspired by Leonardo's drawings. These machines almost never worked in reality. In Virtual Leonardo, they appear in full scale and fully functional. While the real museum offers some wooden working models that can be operated by the museum staff, the virtual museum shows you what is not possibile to recreate in reality, and allows you to touch whatever you want.

Among the available machines there is the famous Aerial Screw, the Pulleys, the Lagoon Dredge, the Parachute, the Pile Driver. Beside each machine you can click on the info billboard to jump to the related web page of the museum.

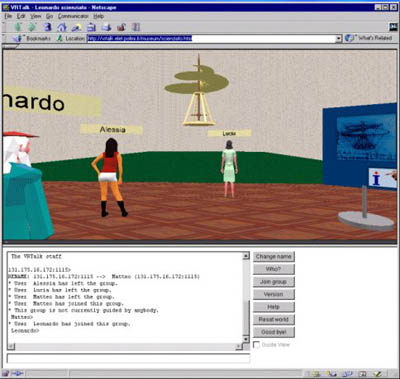

Figure 1: Four users (three in sight, and one viewing the scene) are looking at the Aerial Screw flying. They have been reading the explanations provided by Leonardo's avatar, and they are ready to click on the billboard to read the related page.

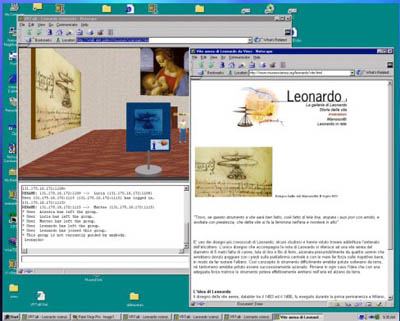

Figure 2: Linking 3D space with the related 2D web page, it is possible to be guided by somebody else to discover information you might have overlooked following 2D links or using a keyword search all by yourself.

The server went live on June, 7th 1999, and it is still running at present. There is generally free admittance to Virtual Leonardo, and everybody is allowed to connect and visit at any time. However, from time to time an expert from the museum staff might organize a virtual guided tour, using an avatar shaped in the form of Leonardo himself. This way, he can lead the cyber-visitors to a 3D tour with an explanation of the machines. Nobody really needs to be at the museum to do this, not the visitors nor the guide. A virtual tour was successfully demonstrated at MW99 and at ICHIM'99, where the virtual guide led the audience around to the discovery of Virtual Leonardo.

In six months (between Jun, 7th and Dec, 31st 1999), the system itself was hit 1547 times. This figure includes all trials to get connected, even by people who didn't have the proper software installed. Successful connections by people who managed to start the virtual system numbered 501. This was more or less expected, as loading a page with VRML graphics and a Java program has more requisites than a simple web page, and the user has to be prepared in advance. Even if there is an installation page in which is clearly stated what is needed to run Virtual Leonardo, most people give it a try all the same, even without the proper software installed.

The total contiguous time spent by all users in Virtual Leonardo was 6,975 minutes, which is approximately 116 hours. The visitors have spent an average of 14 minutes per visit, and the maximum connection time with a user reached 304 minutes, that is around five hours.

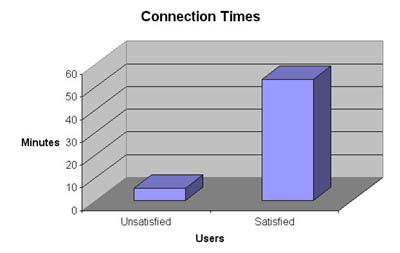

We classify connections under 2 minutes as failed (since in average it takes a couple of minutes to load the system), and connections between 2 and 10 minutes as unsatisfying, because such a short period probably indicates that no cooperation or very little cooperation has occurred between the user and the other participants in the museum. This usually means that the user did not find anybody to interact with, just strolled around a bit and then disconnected. This leads us to a primary rule: cooperation mechanisms work as long as there is somebody else to cooperate with. Trivial as this might sound, great effort has to be spent to keep the cooperative environments populated. The majority of cyber-communities play on the sense of personal ownership. They let you build or rent some virtual space, so you connect often to look at your building or piece of virtual space.

A virtual museum should offer guided tours led by an expert at predefined times, attracting visitors willing to learn something in an innovative and entertaining way. It is this technique, together with continuous updating of contents and simplicity of use, that brings satisfying connections (above 10 minutes) into the system.

Virtual Leonardo got 148 (30%) failed connections, 251 (50%) unsatisfying connections, and 102 (20%) satisfying connections. Unsatisfied users kept the connection open for an average of 5.5 minutes, while satisfied users have been online with the system for an average of 53.5 minutes. Such a difference in connection times stresses again the primary rule of cooperation: when there is somebody else, the system works and keeps you on for almost one hour.

Figure 3: The bar diagram shows average connection times between unsatisfied and satisfied users. The satisfied users stay connected way longer!

Even if this is a bad thing to do (for privacy reasons), we logged all conversation, and we observed that conversation in the museum is always sparse, like "hello, anybody in here", or "where are you?", or "how do I make this thing work?". This changes completely when there is a guide leading a tour and moderating conversations. In this case the topics were often focused on Leonardo, on flying principles, and on the 'Last Supper'.

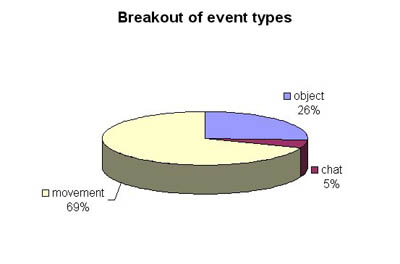

Another interesting observation stems from the data gathered on the different type of actions. In broad lines, a user can move his avatar, use an object, or type a line of chat. During the observation period, the users generated 105,049 events, of which 5% were caused by chatting, 26% by playing and touching the exhibits, and 69% by moving around the virtual space.

Figure 4: The diagram breaks out the types of events in Virtual Leonardo. There has been a lot more walking than talking!

This has both technical and natural reasons. Technically speaking, the system does not make a good optimization of movement events, overloading both the network and the logged data. On the other hand, it is true, also from personal experience and from direct observation of other people using the system, that in general one is more concerned with moving and exploring than typing messages. Secondly, moving and typing proved awkward, and in the end most of the users just chose to move around and spare the talking. This has only in part to do with the difficulty of coordinating mouse movements and keyboard typing. It has been observed in other Cooperative Spaces with vocal communication systems, that movement in virtual space and using the movement commands reduces intercommunication (Ellis). Moreover, a problem which has still to be solved in a satisfying manner is coordinating vocal communications within a large group without creating confusion. Probably the one-liner chat metaphor is still the best solution at the moment.

Lessons Learned and Future Work

Observing the users reacting to the system, and collecting their praise and their complaints, has been of great importance to define the growth path of our project.

The general idea worked and attracted visitors. The museum staff was thrilled to have the possibility to discuss Leonardo with working models in full scale, and to the broadest audience possible ñ the world.

The problems, however, are still many:

- Technical issues proved to be an insurmountable barrier for less experienced users.

- It is difficult to add contents to the 3D museum, because it requires a person proficient in VRML programming and not just a modeler. This leads, in the end, to two parts of the web site to mantain, the 2D part and the 3D part, with the 3D part lagging behind.

- In general, one needs more people at the site at the same time. As this is not always possible, it is important to supply automated guides or pre-recorded paths to follow, in order to allow cooperation at least with the robots if not with other people.

- The user interface could be greatly enhanced, and could support a richer set of cooperation possibilities.

It is absolutely necessary to remove technical difficulties. While it is true that the users' interest in cultural content might help them endure several glitches of the system, by eliminating the technical problems the audience can become broader and the cooperation more effective. This is why the new system will drop VRML and go for an all-Java solution which will work outside the browser. The users will install a dedicated program, and the environment will be automatically installed, just at the price of double-clicking the 'Setup' icon. Using Java, we will also be able to read in 3D shapes written in any technique the museum designer might choose, be it VRML, 3D Max, X3D, Lightwave, etc. Whatever new standard will appear in future, it will be just a matter of adding a new part of the program to load it in.

The link to the existing museum web site could be made tighter or looser. There are two possible strategies to follow here. You could re-create a completely different version of the web site in 3D, duplicating the authoring efforts and mantaining in fact two websites instead of one. This could be the way to follow if the 3D portion of the site has different contents which can be shown effectively only in three dimensions. In this case a tight link to existing 2D content is not needed, even if it could be implemented and used, and the final result is not much different from other Virtual Communities on the web, except maybe that the content is cultural and not focused on idle chatting. You could provide a 3D shell on a web site which already exists and has a carefully designed structure (possibly described with HDM). The 2D web site could also be generated dynamically from an hyperbase of web contents using another technology developed by the HOC Laboratory, the JWEB system. The WebTalk system could then let you choose for the site a different implementation of the same access structure, which uses 3D environments and metaphors. The use of 3D gives the same web site the ability to be navigated cooperatively: you could log in the entrance room, to find a guide in the form of an avatar (linked to a human operator or an automated agent). The guide can lead groups to web pages they might have never discovered without the advise of an expert on the subject. During this navigation, it is very important to provide the user with the most intuitive interface possible. A 2D map might represent the navigation in space to help the user locate other visitors or the guide. Special 3D spots or conveyor-belts might be followed in the space to go to important sections of the museum. Hyperspace jumps and hyperspace bookmarking facilities might be provided. Once you reach a specific area, you could jump to the related portion of the conventional web site. Again, the key here is that the 3D representation could map the existing web site by providing an access structure which is logically the same, but augmented with cooperation possibilities (I follow somebody, somebody follows meÖ) difficult to represent in 2D.

Cooperation possibilities might take many different forms. We are defining cooperation elements: small rules that decide what an user can do with other users and with the system. We are then going to combine the elements in sets, called cooperation metaphors. The designer of the 3D web site can decide which cooperation metaphors are to be linked to groups or single users. For example, he might decide that the museum can be visited only by guided groups (rule: groups are preformed and need a guide), and that talking to the guide is allowed but not talking between the group participants (rule: intergroup communication forbidden). These rules, set in this fashion, might be grouped in a metaphor called Restricted Guided Tour and assigned to all users incoming from 1 PM to 6 PM, when a human operator is available for guided tours. Many cooperation rules can be envisioned and we are formalizing them in a chart.

All these ideas will be part of the new platform, WebTalk-II (http://webtalk.elet.polimi.it), of which a running prototype is expected towards the end of the year.

References

Conference Proceedings

Barbieri T., Paolini P, et al.- Cooperative Visits to 3D Virtual Museums, in Proceedings International Conference for Cultural Heritage & MEDICI day, http://www.medicif.org, , September 1999

Barbieri T., Paolini P. ñ WebTalk: a cooperative environment to access the web in proceedings EUROGRAPHICSí99, Milano 1999

Billinghurst Mark, Baldis Sisinio, Miller Edward, Weghorst Suzanne - Shared Space: Collaborative Information Spaces - in Proceedings of HCI International 1997, pp. 7-10 http://www.hitl.washington.edu/publications/p-96-5//p-96-5.rtf

Garzotto F., Mainetti L., Paolini P., Navigation in Hypermedia Applications: Modeling and Semantics, Journal of Organizational Computing, Vol. 6, N. 3, 1996

M. A. Bochicchio, R. Paiano, P. Paolini - JWeb: an HDM Environment for fast development of web Applications - Proceedings of Multimedia Computing and Systems 1999 (IEEE ICMCS '99), Vol.2 pp.809-813

Paolini P., Barbieri T., et al. Visiting a museum together, in proceedings Museum&Web99, New Orleans, 1999

Articles

Dorota Gut, Internet Gazeta Wyborcza, LATAJVCE MACHINY LEONARDA, (The Fantastic Machines of Leonardo), Appeared October 1999 http://www.gazeta.pl/Iso/Wyborcza/Komputer/300kom.html

Matthew Mirapaul, New York Times on the Web: At This Virtual Museum, You can Bring a Date, Appeared June 1999 http://www.nytimes.com

Matthew Mirapaul, Java Industry Connection on Sun's Java Web Site: At This Virtual Museum, You can Bring a Date, Appeared July 1999 http://java.sun.com

Valeria Camagni, PC Professionale June 1999, Con la tecnologia WebTalk navigare nel Web diventa un'attività sociale (With the WebTalk technology, surfing the web becomes a social activity), pg, 246

Ellis, S.R., Representation in Pictorial and Virtual Environments, Taylor and Francis, London, 1991

Kalawsky, R.S., The Science of Virtual Reality and Virtual Environments, Addison-Wesley, Wokingham, 1993

Roehl B. et al. Late Night VRML 2.0 with Java Ziff-Davis Press, Emeryville, 1997

Zyda M., Singhal S., Networked Virtual Environments, ACM Press, New York, 1999

Web Sites

Active Worlds Web Site, http://www.activeworlds.com

Blaxxun ColonyCity Web Site: http://www.colonycity.com/index.html

Hypernix Gooey Web Site, http://www.gooey.com

National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo da VinciVirtual Web Site: http://www.museoscienza.org/leonardovirtuale

NetMeeting Product Home Page, http://www.microsoft.com/windows/netmeeting

OZ-Virtual Web Site http://www.oz.com/ov/main.bot.html

Ultima Online: http://www.owo.com

WebTalk Web Site, http://webtalk.elet.polimi.it