![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

When is the next

Museums and the Web?

![]()

Archives &

Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto, Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

info@ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search

A&MI |

Join

our Mailing List.

Privacy.

Copyright

Archives & Museum Informatics

2000

The Small Museum Web Site: A case study of the web site development and strategy in a small art museum.

Abstract

This paper presents a case study of the development of a web site for the Vejen Art Museum, a small art museum in Denmark, and it aims to investigate how an art museum with very limited resources might realistically make use of the web for publishing information. It is the hope, that this research will be of use to other small art museums contemplating the development of a web site, as it will give an idea of how to calculate the costs involved (both in relation to financial investment and manpower), thereby helping the museum professional define a project and if necessary apply for appropriate funding.

Introduction

All art museums, small or large, share the same mission to communicate to the public about their collections. A web site is a publishing tool and may be used to further this mission. Small art museums in that respect share the same goals as larger institutions, but their circumstances are very different. They are most often understaffed and managing on very limited financial resources, and these circumstances must be expected to impose some limitations on the amount of time, money and effort they are able to devote to developing and maintaining a web site. The goal of this paper is to take a closer look at the problems of small museums with regards to this new medium, by presenting an example of how they may be solved. It presents a case study of the development of a web site for the Vejen Art Museum, a small art museum in Denmark, and it aims to investigate how an art museum with very limited resources might realistically make use of the web for publishing information.

The Vejen Art Museum, which is situated in the south-western part of Denmark relatively close to the German border, was built in 1924 to house the works of the local sculptor and ceramist, Niels Hansen Jacobsen (1861ñ1941). His production still forms the core of the collection, which was, however, soon extended to include works of art by a range of other artists. Today the Vejen Art Museum is specialising in Danish symbolism and art nouveau. At present, the collection holds some 1500 works of art, including both sculpture, painting, graphic art and ceramics. There are around 12,000 visitors annually, a number which the curator would very much like to increase. The museum has two full time employees, the curator and a museum assistant. Part time staff consists of two weekend attendants and a handyman. The museum is publicly funded. However, for any expenses out of the ordinary the curator must put an effort into private fundraising.

The aim of this case study is to investigate three central points:

1. How may a web site fit into the general information strategy of the museum?

2. What are the minimal requirements in relation to financial investment and work effort?

3. How is the work best organised in order to make the process as effective as possible?

The paper is practically oriented. In order to throw light on the above issues it describes the development process and the decisions made, and ultimately assesses the success of the project. In conclusion, answers to the three points of investigation are considered. It is the hoped that this research will be of use to other small art museums contemplating the development of a web site, as it will give an idea of how to calculate the costs involved, thereby helping the museum professional define a project and if necessary apply for appropriate funding.

The Development Process

Initiative

The initiative to develop the museum web site was taken by the curator. The handyman at the museum had basic HTML skills, but he did not have enough training develop a museum web site, nor did his duties leave him time for the task. The author of this paper volunteered to build the site as a project for an MSc Thesis in Information Science.

The timeframe

- Preliminary discussions started as early as January 1999.

- Project start: June 1st 1999

- Project conclusion: the web site was supposed to be finished on November 30th, but in fact the site wasnít fully completed until the end of January 2000.

The stages of the production

In order to get an overview of the tasks involved in developing a web site, it makes sense to divide the process into stages. This overview may serve as a plan which will make it easier to manage the work, but in reality the stages will often overlap. The following description of the development process is based on the account given by Patrick Lynch and Sarah Horton in their book: Web Style Guide: Basic Design Principles for Creating Web sites (Horton and Lynch 1999).

Stage 1: Site definition and planning

An informal assessment of the information strategy of the museum formed the basis for a development of a strategy for the web site. The requirements for the site were specified by the curator and the volunteer in co-operation. At this stage it was also specified who would be in charge of what chores. The large task of finding, editing and authoring the content of the site was divided between the museum staff and the volunteer.

Stage 2: Information architecture

The information architecture of the site was created using diagrams sketched out by the volunteer, and approved by the curator. Lists of content material to be created were drawn up by the volunteer, and it was specified what each person would contribute. Copyright clearance was the responsibility of the curator.

Stage 3: Site design and content creation

The visual design of the site was created by the volunteer and approved by the curator. The design of the content material was left up to the person in charge of that particular piece of text, even though the curator remained content expert, and had final say on all content. Image scanning was the responsibility of the volunteer.

Stage 4. Site Construction

The volunteer created the actual web pages, and published them on her personal web site, so that the museum could follow the process online. During this stage a usability evaluation was carried out in order to test the appropriateness of the site for the intended audience. After the evaluation the architecture was refined. Proof reading and fault finding was done by the museum assistant.

Stage 5. Site marketing

The marketing of the site using electronic means ñ registering with search engines etc. - was the responsibility of the volunteer, while the museum staff had the responsibility of marketing the site in other ways, e.g. including the address in print publications etc.

Stage 6. Tracking, evaluation and maintenance

By the end of the project the maintenance and tracking of the site was the responsibility of the museum staff. An online questionnaire should provide useful data about the audience.

Equipment

The basic equipment needed to build the site was:

- PC connected to the Internet

- Image scanner

- HTML editor

- Graphics package

- Photo editor

- Browsers

As the volunteer had all the equipment to build the site at her disposal the museum was not immediately required to invest in any hardware or software. It was necessary to have a repro company digitise transparencies. For the future updating of the site it may be necessary for the museum to invest in equipment.

Server space

The museum was offered free server space on the local government server. This came with the condition to use a common design identifying the museum as a municipal institution. This idea did not appeal to the museum curator, who had quite a different audience in mind for the museum site than the one planned for the municipal web site. Furthermore, it looked like the plans for the municipal web site would not be realised for a long time yet. After a certain amount of lobbying, the museum was allowed to temporarily publish an individual site on the server of CultureNet Denmark (www.kulturnet.dk), which is run by the Ministry of Cultural Affairs. CultureNet has agreed to host the site free of charge. When the local government web site is realised the museum site may have to be moved.

Information Strategy of the museum

An analysis of museum activities and publications was conducted in order to assess the information strategy of the museum. This assessment formed the basis of the development of a strategy for the web site.

Assessment of the museumís information strategy

It was found that the museum was very successful in promoting its activities and exhibitions in the local area. The institution was well known and well liked, and posters, press releases and ëword of mouthí functioned very well in advertising special exhibitions. What was lacking was a reliable way of promoting the museum and advertising special exhibitions in other parts of the country and abroad. Even though press releases were sent out to national newspapers regularly, they were not published frequently enough for them to be a reliable means of promotion. The museum did not have the budget to buy advertising space. Promotional brochures were distributed in tourist centres in the local area, not in the rest of the country, much less abroad.

It was an ambition of the curator to propagate knowledge of Danish symbolism in Denmark and abroad, both among the general public and among the international community of art scholars. However, she lacked funds to publish the her research results. The curator would like to improve services for school classes, mainly by providing better facilities at the museum, but also by publishing material about the works of art in the collection.

Web site strategy

It was decided, that the primary goal for the web site should be to promote the museum in Denmark and abroad. It should further the awareness of the museum and hopefully fill the gap in the information strategy by advertising the special exhibitions outside the local area and abroad. The web site was to supply practical information (address, contact numbers, etc.) and a taste of what the museum was all about. Programmes of exhibitions and events were content essentials. It was decided to post annual programmes on the site. This way updating could be done just once a year if necessary.

It has not yet been established whether museum audiences are also web users, and whether museum web sites work well in attracting visitors. However, surveys have shown that museum professionals are positive that they are good promotional tools (James 1997; Oono 1998). It was the opinion of the museum curator and this author that the WWW will increasingly be the place where people find information. It is convenient, accessible from the homes of potential visitors, and it is potentially able to reach a large international audience.

The full site had to be available in English as well as Danish in order to serve an international audience. Some information must also be made available in German and Dutch, as most of the foreign tourists who find their way to the museum are from Germany and Holland. The reason for not creating full versions in German and Dutch was simply lack of resources for translation of material. However, the curator felt that a little information would be better than none, and it was decided to publish the texts from an existing museum brochure.

The secondary goal of the site was to contribute to the educational mission of the museum. The curator would like to use the web site not just as a promotional tool, but as a resource of information about Danish symbolism. However, any material demanding regular work on the site had to be avoided. Therefore the museum could not plan to have online exhibitions on the site, and it was decided to concentrate the efforts on the permanent collection. It was decided to include a catalogue of Niels Hansen Jacobsens sculptures, a text which was already available in Danish and English, but had not yet been published for lack of funds. This catalogue would serve as a resource both for school teachers and art scholars.

Target audiences

Characteristics of the primary target audience

- Potential visitors to the museum

- Adults who are interested in art, and used to visit museums, but who may not be familiar with the Vejen Art Museum.

- Familiar enough with the www to feel comfortable using it for information seeking.

The web site had two secondary privileged user groups: school teachers planning visits to the museum and an international audience of art scholars interested in symbolism.

Design requirements

The site must appear as a finished Two issues were important to the curator:

- whole yet be easily extended, and it must demand as little updating as possible.

- The design of the site must be presentable and appealing to the target audience, and the architecture must be clear and well-structured. It must be easy and fast for the users to navigate the site, and find the wanted information.

Web Solutions

Information architecture

The homepage is a representative front page, designed to need no updating. It contains very little information: the museum logo, a photograph of the museum, the address and contact numbers, and four links to the four different language versions of the site.

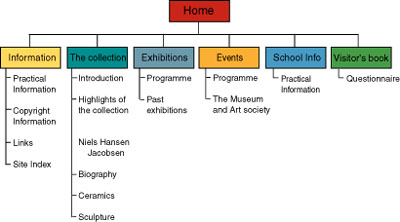

Many art museums choose to advertise the present exhibition on the home page, in order to catch the attention of potential visitors. In order to minimise updating this was not done on the Vejen Art Museum web site. The web site is available in four languages: Danish and English (full versions), and German and Dutch (single page information versions). The layout of the Danish version is illustrated in the following diagram:

Layout of pages

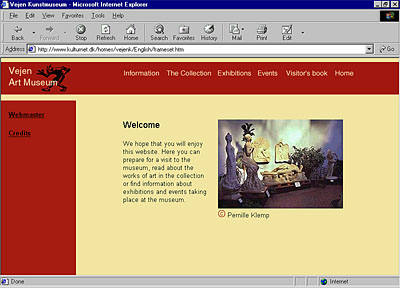

Once the user enters the site, the layout of the screen is as illustrated in the image below.

The pages consist of 4 frames:

|

|

|

|

|

Frames 1 and 2: Visual and navigational framework

The two top frames contain the Vejen Art Museum Logo, and the main menu of the site. This information is present on the screen at all times, and makes up the visual framework of the site. This area was planned as the stable part of the site, where no updating should be required. Therefore it could be laid out with graphic links, and a JavaScript which makes the links light up on mouse-over. These features require more skills than straightforward HTML to update, but they make the site look more interactive and visually pleasing.

Frame 3. Sub menu

The sub menus contain the links available in each category. The sub menu links are pure text links, which do not look as nice as the graphic links, but they are much more straightforward to update. Because frames were used, the sub menus only have to be created once. The menus might have been included in every content page, but this would make creation of new pages more laborious, and it would have meant that every existing page had to be updated if a new link was added. As the structure is now, the museum will be able to add new content documents and update the sub menus very easily.

Frame 4. Main content area

The content documents themselves are straightforward HTML-documents, and a template will ease the creation of new documents.

Updating strategy

In the future the site should be updated at least once a year, when the programmes for the exhibitions and events run out. However, there may be changes which necessitate updating before the end of the year. The museum had two choices as to who would do the updating:

- To pay a web author to do the updating once or twice a year. The museum staff would still have to prepare the material.

- To give the task to a member of staff.

As the museum handyman already had basic web authoring skills it was decided to let him do the updating of the site. This is preferable in that small changes may be carried out when needed. The museum curator will have editorial responsibilities, preparing the material to be published, and the handyman will be in charge of the HTML scripting and publication. This arrangement does place an extra work burden on the museum staff, but hopefully the site structure will make the tasks as minimal as possible. The solution also necessitates that the museum acquire the software and hardware tools to do the updating, so there is a cost involved.

Evaluation of the site

Two forms of evaluation were planned for the site. One was a usability study to be conducted during the production in order to evaluate the layout and architecture of the site. The other was an online questionnaire inquiring into the appropriateness of the content and the information needs of the users. This evaluation would take place after the publication of the site.

Usability Evaluation

The usability evaluation consisted of two steps: a usability inspection conducted by the volunteer and an empirical user test (Nielsen and Mack 1994). The inspection exposed problem areas which were then evaluated in an empirical user test carried out at the museum. Here a PC was set up, and the test subjects either volunteered for the test or were prompted to participate. They were asked their age, gender, familiarity with the Vejen Art Museum and familiarity with the World Wide Web in order to establish to what extent they represented the target audience. They were then presented with 14 test assignments, and observed by the volunteer while performing these. The volunteer took notes and the results were dealt with statistically.

Conclusion to the usability evaluation

The overall result of the evaluation was positive. Most users found the site pleasant and easy to navigate. It was concluded that the overall design and architecture of the site was appropriate for the intended user group. However, the evaluation prompted quite a few minor adjustments to the design and architecture. For example, an alphabetical index of Niels Hansen Jacobsens sculptures was added to the existing chronological one, in order to make it easier to find a specific named sculpture.

The evaluation provided very valuable, useful data, which could be used directly to make design changes, and improve the usability of the site for the target audience. Not only did the user test give answers to the questions posed after the usability inspection, it also brought to light problem areas which had not been apparent to the ëexpertí evaluator. Observing the users was very important, as it was observations of behaviour which provided the most useful material. This kind of evaluation would certainly be within the reach of a small art museum, and even with a small user group the results can be very good. Quite apart from providing useful data about the usability, the evaluation had the added effect of advertising the coming of the site.

Planned content evaluation

It is the plan to further evaluate the site after the publication. This evaluation will be in the form of an online questionnaire on the web site for users to fill in, and this time the evaluation will focus on the content of the site and the information needs of real users. At the time of writing results are not yet available.

Assessment of the project

Management issues

One lesson which was learned from this project is how important it is to have someone in charge of the project. A web development project involves a lot of different tasks, often performed by different persons, and it is essential that someone keeps track of what is going on and who is doing what. During the process of development the curator of the museum became very enthusiastic about having a new publication medium and had a tendency to focus on new ideas instead of the tasks at hand. This was probably due to the fact that the volunteer had the responsibility of the overall running of the project.

The success of the project was very much due to the fact that this volunteer had the dual expertise of web authoring skills and art historical training, and was able to take on a lot of responsibility which could not have been given to a web author with no content understanding. The fact that the volunteer took responsibility for the overall running of the project relieved the museum curator of a great work burden. This, however, may prove to be a disadvantage in the future, as one could fear that the museum staff do not have a realistic picture of the amount of work it actually took to develop the site, and will take to maintain it. It would be preferable to have a permanent member of staff in charge of the project from the beginning. The first stage in the production: Site definition and planning is extremely important. It should include an assessment of the amount of work people are able to devote to the project, and at this stage one should make sure that the involved parties are committed to the project and understand their roles and responsibilities. Ambition and work effort must correspond.

Work load

The amount of effort it took to develop the site would have been very difficult to manage for the museum staff. Without outside help, they would have had to build a much more modest site. Outside help also ensured that the site was built within a reasonable time frame. In this case it came virtually free, but if this had not been the case, the curator would have had to spend time raising money. The main task put on the museum staff was content creation. This proved the weak point of the whole project, as the lack of content was the thing which delayed the publication of the site. The curator could not find the time to write any texts until very late in the project, and this meant that the construction stage was drawn out, and the marketing and tracking stages have only just begun. It cannot be stressed enough how important it is to start small, and to use already existing content on the site. It is better to have a small site functioning well than a large site which is half finished.

It was decided to take a pragmatic approach to the copyright issues. The images mounted are of sufficient quality to be viewed on screen, but they do not print very well and will not be of serious commercial use. A text on copyright explaining the conditions under which it is permitted to copy the images and texts was published on the site. Most of the art works which are presented on the site are out of copyright, so the main issue was to gain permission from the photographers. The amount of work involved in clearing copyrights for this site was not substantial but this will vary considerably depending on the type of collection.

Luckily the museum handyman already had basic web authoring skills, and will be able to do the required updating of the site. The volunteer has made all efforts to make this as easy as possible. The architecture of the site is open-ended, and templates of key pages have been created. The work load involved in making basic changes such as a new exhibition programme is minimal. The museum curator is hoping to do a lot more and develop the site further, but whether this will happen will depend on how much time she herself will be able to devote to the role of web editor.

Costs

The main cost for the museum has been in an extra work burden. The only actual expense has been the digitisation of transparencies, which had to be done by a repro company. The museum was able to publish the site free of charge, which means that the site will be less of a financial burden. The museum already owns the hardware necessary to update the site (PC and image scanner) but may have to invest in software.

Cost of basic hardware and software: Example prices

IBM Aptiva 805 PC: US$ 800.00

HP Scanjet 5200 colour scanner: US$ 249.00

Adobe PhotoShop 5.5 (photo editor) : from US$ 649.00

Adobe Illustrator 8.0 (graphics editor): from US$ 399.00

Macromedia Dreamweaver 3.0 (HTML-editor): US$ 299.00

(These prices are quoted as of February 2000 on the official web sites of the above companies, and are subject to change.)

Cost of professional help

Scanning of images by repro company cost 65 DKr = app. 9 US$ pr. image.

It is difficult to assess how much it would have cost to have a professional company build the site, as these projects are often offered in tenders, and prices stay business secrets between buyer and seller. However, museums that are not looking for very advanced features may be able to employ one of the many semi-professional one-person companies advertising their services on the net. In Denmark I have seen prices as low as 300 DKr. pr page which is app. 42 US$. (This may not be standard at all and may not correspond to American prices.) If we calculate with this price however, the cost of hiring professional help to build the Vejen web site would have been 60,000 DKr. = app. 8,500 US$ as there are about 200 pages. (This amount equals 3 months salary for an entry level museum professional in Denmark, and this probably corresponds quite well with the amount of effective time the volunteer spent developing the web site.)

Conclusions and recommendations

It was the aim of this research to investigate three questions: How a web site might fit into the general information strategy of a small art museum, what the minimal requirements in relation to work effort and financial investment are, and how the work is best organised. Hopefully, the description of the case and the final assessment will have thrown light on these areas, but in conclusion the issues involved should be highlighted.

Information strategy

An examination of the activities and publications of the museum should form the basis of a definition of the requirements of the site. Unless there really is a need for a web site, there is no reason to spend time and effort developing one. On the other hand, a well defined project based on a thorough investigation of the museums information strategy might impress those depended on for economical support. In this case it was found that a web site might be a cost-effective way of solving the museumís advertising problems. Whether this holds true can only be concluded from future visitor studies. Any museum will have to assess their own needs and possibilities before entering on a web project.

Minimal requirements: financial investment and work effort

The amount of work and the costs involved in a web development project will vary considerably according to the existing resources of the museum, and the way they choose to organise the project. Unless a member of staff already has web authoring skills, one can expect a very steep learning curve. It is hard to do it yourself, and it may be more economical to use the efforts on fund raising, and then paying a professional to do the web authoring. Whether to do it yourself must be a decision based on an analysis of the human resources and computer equipment available to the museum. The calculation must consider the following points:

Do it yourself

- Human resources

- Hardware equipment

- Software equipment

- Large initial work load when constructing the site, and continued work in updating.

- Server space

Professional help

- Cost of professional help

- Web editor function of the museum

- Server space (may be part of deal with multimedia company)

Content creation is one of the major tasks of a web site development project, and this work will be the responsibility of the museum no matter who develops the site. The smaller the site, the smaller the work burden. It is a good idea to use existing content whenever possible. The special characteristic of a web site in comparison with a hardcopy publication is that it can be developed after the publication, so one can start out small, and make extensions when possible. A web site should be thought of as an ongoing project, and one should make sure the design is open-ended, so that extensions to the site donít demand major design changes.

Organisational issues

The planning stage of a web project is extremely important. If the ultimate planning is done properly, and everybody sticks to this plan, then everything can be done much more quickly, and with fewer wasted development efforts. It is important to be familiar with the development process before actual work on the project begins, and case studies like this one may serve to this end. It is very important to elect someone to be in charge of running of the project ñ someone who can hold all the strings together. Preferably this person should be a permanent member of staff, so that the museum doesnít loose the overview of the project, and the optimal situation is if this person has organisational power so that he or she may speed up the project if necessary.

Any museum will have to take into consideration their special needs, abilities and circumstances when they consider how to make use of the web. Web Sites are expensive to establish, but, and this point is important to include, if the museum can afford to overcome the initial hurdle, and are able to acquire the skills to publish basic HTML-documents, they are actually in possession of a very cheap publication media, much cheaper than print publications. One possible solution model would be to pay a professional company to establish an initial small site, which could be easily added to later by the museum staff themselves. It is easier to update a site than to build it from the ground. The future will show whether the prices of professional help go down or the skills among museum professionals go up.

No matter what solution model is chosen, having a web site is going to demand work ñ new routines and new responsibilities, and museums must be ready and willing for this change if they want to use the medium. The real strength and value of a case study like this is that the experiences learned may give museum professionals a sense of the tasks at hand.

References

Horton, Sarah and Lynch, Patrick: Web Style Guide: Basic Principles for Creating Web Sites, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1999, chapter 1.

James, Stephanie: Museum Web Page Survey Results, http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~sjames/museum/survey.htm, last updated March 1997.

Nielsen, Jakob and Mack, Robert L. (ed.): Usability Inspection Methods, John Wiley Sons, New York 1994.

Oono, S.: The World Wide Museum Survey on the Web, Internet Museum, Japan, http://www.museum.or.jp/IM_english/f-survey.html, last updated September 1998.