|

158 Lee Avenue ph: +1 416-691-2516 info @ archimuse.com Join

our Mailing

List.

published: March 2004 |

Burarra Gathering: Sharing Indigenous Knowledge

Geoffrey Crane, Questacon, Canberra, Australia

http://burarra.questacon.edu.au

Abstract

Burarra Gathering Online is Questacon's first Web exhibition. The exhibition was based on the interactive, physical exhibition Burarra Gathering: Sharing Indigenous Knowledge, which was Questacon's first Indigenous-based exhibition. The two exhibitions show some of the traditional technologies of the Burarra ("bur-ah-da") people of remote central north Arnhem Land, in Australia's Northern Territory. Both Burarra exhibitions were developed in co-operation with, and the approval of, the Burarra Elders. This paper will briefly outline the development of the physical exhibition and examine in more detail the on-line version. The Burarra Gathering Online development team faced many challenges, including a limited budget, the logistics of having to seek incremental approvals from Burarra Elders in remote communities 4 000 km away, and the usual technical issues these projects involve. Evaluation of the finished products has shown them to be effective in presenting Indigenous technologies in a contemporary context; they have received praise from the Burarra people and many other organizations around the world. The development processes and resulting exhibitions have shown that a close partnership with an Indigenous community can lead to insightful exhibitions that share Indigenous knowledge with the world.

Keywords: Indigenous knowledge, traditional technology, Burarra, Arnhem Land, Aboriginal, Questacon, science museum, Australia

Introduction

This paper will outline the development of the on-line version of Burarra Gathering: Sharing Indigenous Knowledge. Burarra Gathering is Questacon's first on-line exhibition, and it followed in the footsteps of a museum floor exhibition of the same name. Both of the Burarra Gathering exhibitions were made in partnership with the Burarra community Elders.† The organization learned a lot from the development of both exhibitions: in the first place, how to gain and build the trust of a remote Indigenous community, and later, what it means to build an on-line exhibition.

Questacon has had a popular interactive museum Web site since 1995, made up of lots of individual experiences and a virtual tour. Questacon's on-line resources currently attract around 90 000 visits per month from around the world, with about 75% of all visitors coming from outside Australia.

As this paper is being written, an external research project is underway to compare the learning outcomes of the physical and on-line versions of Burarra Gathering. It is hoped that the research findings will be available at Museums and the Web 2004.

Burarra Gathering: †Physical Exhibition

Recognizing Indigenous Technologies

The physical exhibition opened in February, 2002, and marked a number of significant firsts for Questacon. Burarra Gathering was Questacon's first Indigenous exhibition, and the first that used no text to interpret the exhibits. The only text in the exhibition was at the entry, where a map showed the location of the Burarra land and a list of credits to thank the people who had assisted in its development or been involved with the project.

The main reason for having no text was that Questacon did not want to put a Western 'spin' on the practices shown in the exhibits. The intention was to let the Elders speak for themselves in the exhibits. Audience observations showed that users took a while to realize this – they looked for the instructions to find out what to do. After a short time they had a go at the activities for themselves, with the Elder telling them what to do. The exhibits are triggered by motion sensors once a visitor approaches quite closely, and other sensors are used to determine the kind of feedback to be given, be it encouraging: 'that's good,' or instructive: 'No, no! Faster, faster!'

In late 2000, Questacon's leadership team decided to fund the development of a new exhibition with the aim (Questacon, 2000) to 'recognise the significance of Indigenous technologies to 21st century Australian culture' and 'to provide a medium for Indigenous communities to disseminate cultural information to the wider community'.

The exhibition development team called on the help and expertise of Linda Cooper, who in the past had worked with many Indigenous communities and the Investigator Science Centre in Adelaide. Linda had previously worked with the Burarra people and suggested that they would be good for Questacon to work with, as they are still living on their own land and they have retained many of their traditional practices:† the region has seen fairly limited development, and their land is quite small and does not range far from the coast. Linda felt that it would be reasonably easy to identify a set of technologies based on the lifestyle in this area.

Going Outback to Burarra

After being introduced to the community by Linda, members of the development team made three trips to visit the Burarra people in Arnhem Land during the 2001 dry season. The first of these trips was really just an ice-breaker, but on subsequent visits the Elders opened up and showed the visitors the traditional knowledge and technology that would be used in the exhibition. The team gathered the video, audio and still photographs they needed to build the museum floor exhibition. Unfortunately, the team was not able to learn anything about the traditional practices of the community's women and girls, so the exhibition only features men. The logistics of these trips were tricky. The community is a seven hour, 520 km drive or one and half hour flight east of Darwin, which itself is 4 000 km north of Questacon in Canberra. Additionally, all visitors need to secure a travel permit to go to Maningrida, the nearest large settlement (population 2 600) with an airport. Permits are issued by the Northern Land Council in Darwin and have to be signed and approved by the community Elders. These permits are not issued as a matter of routine. Even though our team had been invited, they still had delays of a few days in Darwin waiting for their permits. These delays added greatly to the cost of the trips

Fig. 1. Map of Arnhem Land

What's an Exhibit?

Some other problems were cultural in nature: the Elders didn't know what a hands-on science centre was, let alone an exhibit from such a centre. The team members took sketches and model mock-ups of exhibits to try to get across a sense of what these things were. It took some time to work through these problems and to develop a sense of trust between the Elders and their visitors. The community had had bad experiences with anthropologists and others in the past, and at first they were wary of the Questacon team.

Building the Exhibition

The development team sought community approvals at several stages in the exhibition's development, including the basic concepts and topics, the exhibits' design, how the user would interact with the exhibits, and the final exhibits both while they were being constructed and after they were completed. This was done both in person on the later trips and remotely via post, telephone and e-mail.

Gaining incremental approval was seen as necessary for two reasons; to give the Elders ample opportunity to shape the representation of their knowledge, and to give Questacon a better chance of making changes at lower cost. If the exhibits were finished and then rejected, much more money would need to be spent to fix or replace them.

The approval process impacted somewhat on the exhibition timeline, but in the end the final exhibition was built and opened on time for the 3rd Science Centre World Congress that Questacon hosted in February 2002. The exhibition gallery looked as if it were a part of Arnhem Land, with huge panoramic photographs lining the walls and tree branches reaching overhead.

The Burarra Gathering exhibition consists of five exhibits:

Seasonal Calendar

This is a round house where each of the quadrants shows a scene typical of four different times of year. An Elder describes the weather and activity in the community for each season.

Fish Trap

Catch a barramundi! You have to crouch and hide so the fish will swim into the fish trap. You might also see a croc down by the billabong.

Navigation

You have to steer an outboard motor dingy back home to Yilan, at night, using the stars to navigate around a headland and up a river. You might also notice how the waves under the boat change as you round Cape Stewart and later travel up the Blyth River.

Making Fire

You have to use the rubbing stick to make a fire. Put it in the hole in the bottom stick and turn it really fast.

Tracking

What animal tracks can you find in the tidal mud flats?

Fig. 2: Burarra Gathering in Questacon's Gallery (image by Jim Spadaccini, Ideum)

The finished exhibition was given a “10 out of 10” by Burarra Elder Peter Danaja when he visited Questacon a few months later. This was very satisfying for the exhibition developers, as the approvals and feedback from the community up until then had been based on photographs, video and written materials like the scripts and exhibit storyboards.

And in 2003, students from the school in Maningrida got a thrill to see the Elders from their community in the Burarra Gathering exhibits, when they visited Questacon while in Canberra on a school excursion.

Taking Burarra Gathering Online

When Burarra Gathering was first opened to the public, I thought it would be a great opportunity to make an engaging on-line companion exhibition, as the exhibits were simple and largely featured video of the Burarra Elders. As the exhibits were largely one-on-one experiences between the Elder and the user, I felt they would translate well to the on-line environment. Unfortunately, at that time there was no funding available for any on-line development of the exhibition.

Later in the year Questacon's parent Government Department was looking to fund a study that directly compared the learning outcomes between the physical and on-line versions of a single exhibition. At that time no such exhibition pair existed in the Department's cultural institutions in Canberra, including the National Gallery of Australia, the National Museum of Australia, Questacon, and ScreenSound – the National Film and Sound Archive. Questacon's then-director Dr Annie Ghisalberti had had an interest in on-line learning outcomes, so she volunteered Questacon for the study, and committed to develop an on-line version of the new Burarra Gathering exhibition. Questacon allocated A$100 000 (US$50 000 at that time) to the on-line production.

The reasons for choosing Burarra Gathering for on-line duplication were that it was new and that it had only five exhibits. It was also thought that the Indigenous theme would be of interest to a global audience. Annie's initial thinking had centered on the development of five interactive (Shockwave or similar) on-line exhibits that closely replicated the gallery experiences. In other words, that the on-line exhibits would be simulations of the gallery simulations. The first meetings of the on-line exhibition team convinced her to broaden her thinking to allow the team the freedom to come up with an exhibition that they felt best conveyed the message.

A Better Model

As this was the institution's first on-line exhibition, the first task the team faced was to research what 'on-line exhibition' might mean. The team searched the Internet for existing projects and also drew on a Museums and the Web 2001 paper (Sumption, 2001). The team settled on the electronic field trip mode, and used the Brookfield Zoo's In Search of the Ways of Knowing Trail (Brookfield Zoo) as an example when pitching their concept of an animated adventure to management. In fact, Brookfield Zoo's Dr Keith Winston was very supportive of our project, at both the initial stages and as it was nearing completion.

The project team settled on a virtual trip or adventure style because it offered the best opportunity to simulate the learning style of the Burarra people, with an Elder demonstrating an activity and then encouraging the 'students' to have a go themselves. This is what happens in the physical Burarra Gathering exhibition, using video on portrait–mounted plasma screens. As the on-line project budget was not sufficient to return to Arnhem Land to shoot new video for the Web exhibition, the team decided to instead use animated characters to tell the story. To add a level of realism, it was then decided to place those characters on 'real' backgrounds. All of the background images that were used were photographs taken on previous trips to the region.

The physical exhibition has five exhibits that each deal with a different sort of traditional knowledge or technology: fish traps; animal tracking; making fire; navigation, and the Burarra seasonal calendar. These were the only topics that were shared with the original exhibition development team, and so were the only ones available for the on-line exhibition. In any case, the online exhibition was being driven by the research opportunity so it had to deal with similar material to the physical exhibition.

Storyboarding

The original storyline had some more 'branches' to the wet and dry season adventures than the finished exhibition has. But essentially, the original sketches for the flow of the story developed into the finished product. The intention was always to represent a busy day, where the visitor is able to try out or observe some of the indigenous technology along the way. While some of the experiences overlap between the wet and dry season visits, these two parts of the adventure were designed to be complementary, not just done in isolation from one another.

The reason for splitting the adventure into wet and dry season is that the Burarra people's seasonal calendar is itself an exhibit in the physical exhibition, and we wanted to highlight it the on-line version. Additionally, some of the technologies can only be used at particular times of the year. For example, fish traps are only used in the wet – the billabongs are empty in the dry!

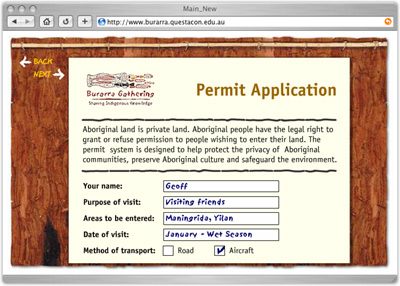

Invitations and Permits

Aboriginal land in Australia is private land, and it is against the law to visit without a permit. In many areas these permits are not routinely issued to tourists just wanting to see the area - you must be an invited guest. This is the case for the Burarra people's land.

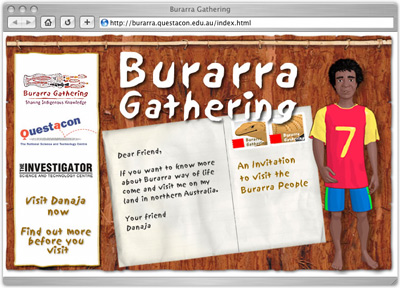

The on-line exhibition development team struggled with 'inviting' people to Burarra when in reality they could not go there. In fact, this proved to be so hard that the team decided to leave it until we had written the adventure, to see if a solution presented itself. In the end that is what happened, and at that stage we felt it seemed obvious that Danaja would have invited his friend (the user) to visit him. This is what happens in the initial stages of the on-line exhibition: when you receive a letter from Danaja, choose which season you visit in (wet or dry season), and apply for a permit to visit the Burarra people's land.

Fig.3: Burarra Gathering Visitation Permit Application

Burarra Approvals

The biggest risk to the project was not obtaining the final approval of the Burarra Elders, as by that time there would have been no money available to substantially change the exhibition. Consequently, we sought incremental approvals throughout the life of the project, involving the community in the creative process. The on-line exhibition was not put on-line until we had received the final signoff from the community.

Fig.4: Preliminary Website Sketch

We flew Peter Danaja down to Canberra for an intensive two days, working through the adventure storyboards, and then the script, word for word. While Peter was happy with the team's work, he made many suggestions to improve the script. Peter also added in all of the Burarra words that are heard in the dialogue.

Peter made other suggestions to the storyline, including adding some of the humorous interplay between the characters, and having Wala-Wala forgetting his matches in the fire lighting sequence. The exhibition team had carefully tried to avoid making him look foolish, but Peter thought he would just as likely be forgetful!

While he was in Canberra, we took the opportunity to film Peter reading the script, performing the kinds of gestures that are seen throughout the animation.

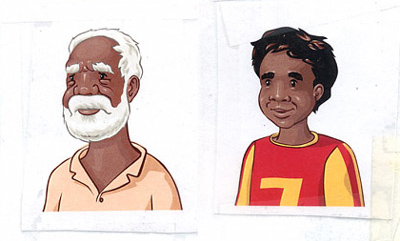

Aging Danaja

One of the more interesting approval stages was for the character renderings. The drawings were both e-mailed and posted up to Arnhem Land. While the Elders were happy with the general look of the characters, they were uneasy with how young Danaja was.

Danaja had been drawn to look about 12, the age of the targeted audience. The problem was that a 12-year-old would not have the knowledge that Danaja needed in the adventure. Once Danaja had been made bigger and given more prominent facial features so that he looked to be 15 or 16, the Elders were comfortable with him.

The Elders also thought that Wala-Wala looked far too neat – 'he's an old guy from the bush!' So we made him look a bit scruffy!

Fig. 5. Original Character Drawings

Fig. 6.† Final Approved Characters

Finding Voices

The Burarra language is considered to be endangered, and is spoken by less than 600 people. The exhibition team was keen to put some of the Burarra language onto the Web in the adventure and to make the characters as real as possible.

The development team was concerned about how to record the voices of Burarra people for the soundtrack without being able to afford to send a Director and/or Sound Operator all the way to Arnhem Land. There was no recording studio available there anyway, and we also wanted to video the voice actors so that the animators could get the lip-synching right.

We considered flying two Burarra people to Canberra to do the recording, but again there really wasn't enough money to do that. In the end we asked Peter Danaja if he thought local Canberran (Ngunnawal) Indigenous actors could do it. Peter agreed, but said he would like to train them on the pronunciation of the Burarra words. The coaching was done by telephone, and the recording was made in a studio that was generously donated by the National Museum of Australia. It was a very long day, recording each line four times over. Peter was happy with the final sound files, and that allowed us to proceed with lip-synching the animation.

Refining Burarra

Just before the exhibition was launched, invaluable user testing was done in the Usability Lab session at Museums on the Web 2003. Suggestions included changes to the placement of instructions in the interactive adventure and also to the information on the introductory page. The changes made for a much more intuitive experience, and stopped people getting 'lost' as they moved through the activity. I would also like to acknowledge the valuable suggestions made at that time by Jim Spadaccini of Ideum.

The development team also trialed the experience with some school teachers and their students in Canberra prior to launch, and again some useful suggestions were made and changes implemented.

Many of the school's suggestions related to the feedback given by Danaja and Wala-Wala in the interactive activities. The feedback itself was fine, but the users were not noticing it when it appeared on the side of the Web page. Once it was moved to centre stage (where the subtitles appear), users saw it straight away.

Jumping Onto the Web

With all the improvements made and final approval received, Burarra Gathering Online was launched on 22 May 2002.

Fig. 7. Burarra Gathering homepage http://burarra.questacon.edu.au

Usage peaked in July at 6 500 visitors and has settled back to around 3 000 per month. Around half of the visitors are from North America, and 15% are from Europe.

Feedback

The first essential feedback was from Peter Danaja and the other Burarra Elders when they approved the whole of the completed project for release and linked to it from their community Web site.

Questacon received international recognition soon after the release of Burarra Gathering: Sharing Indigenous Knowledge online. The Exploratorium awarded it a Ten Cool Sites Award for 'educational excellence'; USA Today made it a 'Hot Site' for the July 4 holiday; Yahooligans featured it; and there were articles in the on-line versions of The Sydney Morning Herald (2003) and The Guardian (2003).

The most rewarding feedback was learning that the site had been used in its first weeks in an education program that introduced the Internet to school students in remote central desert Indigenous communities centered on Alice Springs. Even though these students live about 2 000 km away from Burarra and the coastline, they still saw the Burarra experience as a reflection of their own culture. The development team saw this as a special affirmation of a job well done.

We received this special feedback by accident when I interviewed an educator in Alice Springs on a totally different topic.

The site has also been recognized as a valuable Indigenous on-line resource by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) and other government and educational bodies in Australia, including AMOL, EdNA and some of the various State school authorities.

Recently the Akva natural science centre in PiteŚ in northern Sweden approached Questacon and asked if they could display Burarra Gathering Online on their museum floor. We were happy to let them do this, and it will go ahead in 2004. Ulrika Nilsson, the Director of Akva, made contact via the user feedback e-mail address on the Burarra Gathering Web site.

Fig. 8. Celebrating Questacon's

15th birthday, November 2003.

†(L-R) Special guests, Burarra Elders Horace Wala Wala & Peter

Danaja with Questacon Deputy Director - Programs, Neil Hermes and Burarra

Gathering's Project Manager Jenny Dettrick

Evaluation

The original impetus for the development of Burarra Gathering Online was the evaluation of the learning outcomes achieved by physical and on-line versions of the same exhibition. As this article is written, that research project is underway, and it is hoped that the research findings will be available by the time of the Museums and the Web conference in March 2004.

The main aim of the research project is to 'show how online exhibitions can inspire, entertain and potentially change visitor attitudes relative to onsite exhibitions'. It is hoped that the report will be a useful tool used in deciding the allocation of money for the mix of physical and on-line exhibitions for a number of Australia's national cultural institutions.

The research will include observations of visitors in the Burarra Gathering gallery and people using the on-line version, interviews with selected visitors and users, and focus groups of both adults and children who have used both modes of the exhibition.

Conclusion

The two Burarra Gathering exhibitions have shown Questacon that indigenous knowledge can be represented in engaging exhibitions, both physical and on-line. Burarra Gathering also allowed the Centre to experiment with the development of on-line exhibitions, and Questacon is very proud of the positive recognition Burarra Gathering Online has received from around the world.

Perhaps most important, the two exhibitions required the nurturing of a close and trusting relationship with a remote aboriginal community on the other side of the country. And while the production process was delayed by gaining the various approvals from the community, we feel that the end product justified the extra time and expense involved.

It's exciting to know that Questacon will be putting this new knowledge and expertise to use in the near future, with a new project that will again allow some Indigenous communities to tell their own stories on the Web. This will most likely be done with communities in the Gulf of Carpentaria in Queensland. Hopefully we can let know about that at next year's conference!

References

Brookfield Zoo, In Search of the Ways of Knowing Trail. Consulted 17 December 2003. http://www.brookfieldzoo.org/pagegen/wok/index_f4.html

The Guardian, Web Watch, Jack Schofield 17 July 2003. Consulted 18 December 2003. http://www.guardian.co.uk/online/story/0,3605,999224,00.html

Questacon, Indigenous Science & Technology Exhibition Proposal, November 2000. Questacon Internal Document.

Sumption, K. (2001), "Beyond museum walls" -- A critical analysis of emerging approaches to museum web-based education. D. Bearman & J. Trant, Museums and the Web 2001 Papers, http://www.archimuse.com/mw2001/papers/sumption/sumption.html

The Sydney Morning Herald online http://www.smh.com.au (article no longer available)