|

158 Lee Avenue ph: +1 416-691-2516 info @ archimuse.com Join

our Mailing

List.

published: March 2004 |

Web site as Tour-Guide: Getting Visitors to ask the 'Good Questions'

Edya Kalev, Web Content Manager and Colonial Role Player, Plimoth, Plantation, USA

Abstract

Web sites can serve their institutions as calendar, advertisement, or textbook. However, they can also be used as an important tool for visitor orientation, encouraging positive and satisfying interactions between visitors, exhibits and staff. Using the newly redesigned Plimoth Plantation Web site as a case study in content development, this essay will provide practical ideas for turning your Web site into an electronic tour-guide, beginning the orientation process long before visitors reach your front door.

Keywords: electronic tour guide, orientation

For the ninth time that busy morning, a visitor asks Goodwife Billington why she isn't preparing for Thanksgiving. She looks up from her stitching with a skillfully composed expression of bafflement and remarks, 'Why Master, what a curious question. Our town is not holding a day of Thanksgiving today, although we had one some several years ago in 1623. In the dirt path nearby, a young mother with a stroller, tour map in hand, stops Governor Bradford and inquires about Mayflower II, 'Can we walk to the boat from here?' The Governor feigns confusion, 'Mistress you would have to walk back to Olde England to find that ship!' A short distance away in a recreated Wampanoag home, a second grader is quite taken with the handmade deerskin clothing and bead necklaces of the interpreters. Wide-eyed, he asks a Native staff member, “Are you a real Indian?”

These three scenarios are repeated over and over again at Plimoth Plantation, an outdoor living history museum in southeastern Massachusetts. The museum includes a recreated 1627 Pilgrim Village, a full-scale reproduction of the ship Mayflower, a recreated 17th-Century Wampanoag Homesite, rare-breed animals, and an indoor exhibition area. In the first scenario, a visitor to the Pilgrim Village (staffed by role-players who cannot break 17th-Century character) is asking a question based on the popular myth that the English colonists celebrated Thanksgiving each year in November, a practice initiated by President Lincoln over 200 years later. In the second scenario, a seemingly simple request leads to a confusing and unsatisfactory answer by a role-player, who cannot give modern-day directions. It gets worse in the third scenario, with the unsuspecting visitor asking an offensive question to a staff member who is not role-playing as a person of the past, but is a modern-day member of the Wampanoag Nation.

Are these people 'bad visitors'? No! But they are asking 'bad questions' - questions that can frustrate and confuse both visitors and role-players; questions that can hinder deeper learning about 17th-Century history; questions that are asked with such mind-numbing frequency that they strain the front-line staff. And questions that can create an embarrassing situation although they are often asked with the best of intentions.

Institutions far and wide, from eclectic living-history museums like Plimoth Plantation to conventional art museums, from science centers to children's museums, from zoos and aquaria to small historic house museums…every institution has its own set of 'bad' questions to contend with. But the good news is that there are ways to limit or even eliminate the bad questions, improving both the quality of the visitors' experience and the workload of your staff…and it starts with thorough orientation.

The words museum orientation usually conjure up visions of indecipherable floor plans, fuzzy explanatory videos, gruff security guards pointing the way to the bathroom, and museum tour guides whose eloquent words get lost in the crowd. We all know from personal experience that this kind of on-site orientation is often marred by time and space constraints, noisy surroundings, impatient children, or 'museum fatigue'. Off-site orientation, on the other hand, does not have such limitations. At home, in their own time, people can learn all about the museum before they even set foot on the grounds. They can pinpoint the location of the different facilities, read about common myths and misconceptions, and feel confident, comfortable and prepared to ask good questions once they arrive. What is this dynamic and effective home orientation tool? Your museum's Web site, of course.

Museum Web sites traditionally function partially as an advertisement or corporate branding device, partially as a calendar of events, and partially as an on-line information desk for their institutions. They contain information about program listings, special events, as well as admission fees, hours, directions, and parking information, and have lovely images to entice visitors. For some museums, Web sites also act as a kind of on-line textbook, with searchable databases and scholarly articles on a particular topic. These are certainly fundamental services for your Web site to provide. However, it can be more than an advertisement or textbook. Your Web site can serve as your very own electronic tour guide, welcoming and informing visitors long before they reach your front door

Using Plimoth Plantation's newly redesigned Web site as a case study, this paper will provide practical ideas and tips for turning any museum Web site into an electronic tour-guide. It will take you through our planning and content development process to share what we have learned about the following:

- How to begin: Looking at what you have

- Identifying the sources of visitor confusion

- Using the What you will see / Who you will meet format

- Encouraging good questioning skills and cultural sensitivity in visitors

- Using maps, rollovers and other eye-catching devices

- Web site navigation and design

- Aligning Web site content with other museum orientation materials and initiatives

- Brief review of Plimoth Plantation's Web site statistics and visitor feedback

How To Begin: Looking At What You Have

Plimoth Plantation started the process in the only place we could: we looked at what we already had on our Web site. The site was huge, over 2,500 pages, and not clearly organized or easily navigable. Some of the material was outdated, unnecessary or outside the mission of the museum. The overall look, feel, and color scheme did not promote our corporate 'brand' or identity as a world-renowned living history museum of the 17th Century. It did not give a strong sense of what the museum was about or what visitors could expect to see. However, the Web site was rich in historical background and provided interesting bits of information about various aspects of early colonial life.

TIP #1: Evaluate your current strengths and weaknesses

Your Web site may have some of these problems too…or not. But these kinds of issues must be addressed before embarking on any new Web site project, much less one that involves improving the visitor experience. So, begin by making a list of the strengths and weaknesses of your current Web site. Then brainstorm ways to preserve or promote the strengths and remedy the shortcomings. You can divide the list into short and long term goals to help in the next stage of the process.

If possible, invite someone not on staff but familiar with your museum to participate in this exercise. At Plimoth Plantation, we were fortunate that a long-time Executive Board member was able to give us a broader view of our needs. Outside Web designers or consultants can also help evaluate your Web site with fresh eyes.

TIP #2: Plan your approach to the project

After your evaluation and brainstorming session, you will have to make various decisions about how to approach the project from a scope/time/money standpoint. Like Plimoth Plantation, you might decide to build a brand new Web site rather than try to adapt the old one. Alternately, you might want to try a temporary fix and worry about a complete overhaul later. You may do the work yourself in-house, create a new position, or hire an outside design firm while maintaining control of the content, as we did. After an extensive search and interview process, Plimoth Plantation hired Brown & Company out of Portsmouth, NH, to do our redesign (http://www.browndesign.com). Brown had extensive experience working with other museums and non-profits and was able to guide us through unfamiliar territory with a patient hand.

TIP #3: Plan your staff involvement

In this final preparatory stage, ask yourself which staff members should be involved with the project, including writing, reviewing, or approving the content and providing the pictures. At Plimoth Plantation, it was important to us that we incorporate the multiple perspectives of our diverse staff. We included our Native staff in the process from start to finish so their viewpoint would be accurately and appropriately represented along with the Anglo-Protestant story of colonization. To accomplish this, we found it best to work in groups of three around a computer to edit material and then send it off for approval by a set date. Whatever your content gathering method, make sure it is a collaboration among a manageable number of people and that the steps in the approval chain are clearly defined to include all the key decision-makers. If you have hired an outside company, make sure all the content that reaches them is pre-approved and ready for programming.

Identifying the sources of visitor confusion

It is all too easy for managers, particularly those who sit in front of a computer all day, to lose touch with what really happens in their own museum's galleries and exhibits. To make your Web site a guide for visitors, you have to understand what areas they need guidance in and where they frequently experience confusion.

At Plimoth Plantation, we are fortunate that many of our administrators were once on the front lines interacting with visitors. Indeed, the core content development staff, (Kathleen Curtin, Guest Services Manager; Lisa Whalen, Village Program Manager; Nancy Eldredege, Wampanoag Education Manager; and myself) all continue to divide time between behind-the-scenes efforts and working at our various outdoor museum sites with the public. So it was quite easy (and often entertaining) for us to come up with a list of 'bad questions' that visitors always seem to ask. However, it might not be so easy for you if you haven't rubbed shoulders with your visitors for a while.

TIP #4: Gather frequently asked questions (FAQs)

Get out from behind your desk! Tour the museum, shadowing different groups of people. Observe tour groups, families, couples, and children of varying ages interacting with the museum environment. Take notes if possible.

Talk to your visitor services staff at the admissions desk, information desk, and membership booth. Chat with museum shop and housekeeping personnel; chances are they can rattle off at least five sources of visitor confusion from the top of their heads. Follow guided tours and notice which questions are asked over and over. Not only will you come up with a comprehensive list of frequently asked questions, but you will also make new friends!

If you have hired an outside design company, insist they spend some time visiting your museum. Members of the Web Department from Brown & Company toured our museum several times before sitting down with our staff to plan the Web site. As new visitors to the museum themselves, they had many important insights to contribute to the process.

TIP #5: Organize the FAQs into clear categories

At the end of our FAQs survey at Plimoth Plantation, we had compiled a list of more than 70 questions. Obviously, that was too many…or was it? Like many museums, we feature different exhibits on a variety of topics employing different interpretive techniques. Some of our exhibits are indoors, many are outdoors; some use live people, others use images, text and video; some use first-person interpreters (role-players), some use third-person guides, and some use both.

Looking at the list, we found that the questions could be categorized into logical sections according to the exhibit, topic and mode of presentation. Interestingly enough, visitors also seemed fascinated by how we do what we do - what training our staff receives, and what kind of people work at our museum - all of which would be difficult, inappropriate, or downright impossible to answer in our recreated Pilgrim Village. In addition, many questions were related to the practical aspects of visiting, such as where to find the bathrooms (important when visiting a recreated 17th Century village full of chamber pots!), what to wear, or how long a visit might take.

As you can see from Figure 1.1, we came up with the following categories of FAQs, ranging from the particularities of each part of the museum to more general information about visiting:

- What to Expect, How to Prepare

- Frequently Asked Historical Questions

- Behind-the-Scenes Questions

- Practical Questions About Visiting

To maintain consistency, we prepared these categories for each of our main exhibits. At your museum, you may have fewer exhibits, or different kinds of questions, but you will most likely find a pattern to the FAQs you compile.

Figure 1.1: The four categories of Frequently Asked Questions.

TIP #6: Answer the question asked

It seems an easy task to answer the questions…after all, you've probably heard most of them dozens of times. Yet this was something that Plimoth Plantation staff struggled with for some time. The difficulty is striking a balance between telling visitors too much and leaving them wanting more. You don't want to confuse them, or worse, bore them with too much background information, yet you don't want to talk down to them either. You might find yourselves over-analyzing, quoting period sources excessively, or using 'museum speak' unfamiliar to most non-museum people. Take a step back. Remind yourselves first and foremost to answer the question asked. If it is a yes or no question, answer with a yes or a no and then elaborate. If the available research provides no definitive answer to a particular historical question, cite the sources briefly and try to venture an educated guess. If it is a culturally sensitive question, say so, explain why, and provide some examples of more appropriate questions to ask. However, some explanations may be misunderstood or even challenged, so you may want to provide an e-mail address for visitors to send follow-up questions.

TIP #7: Make it conversational

Just like a live tour guide, you want your questions and answers to be friendly and clear. The questions should be phrased the way the visitors most often ask them, even if they are inherently problematic (like the 'Are you a real Indian' question noted above.) The answers should be written in a conversational style, and a little humor is always appreciated. Keep in mind your professional museum voice; that is, the tone and content in which you answer these questions should reflect the broader museum's approach, as well as your potential audience of Web site readers. However, in some cases, especially when the content involves culturally sensitive issues, it is best to let the culture speak for itself. For instance, a Native staff member wrote the reply to the question about being a 'real' Indian.

Of course, shorter is always better for FAQs, but that doesn't mean you can't provide links to other areas of your site or elsewhere on the World Wide Web for further information, especially in the area of cultural sensitivity.

Using the 'What you will see / Who you will meet' format

In the course of our visitor studies at Plimoth Plantation, we found that many FAQs stemmed from confusion on the most basic level. The visitors were confused about what they could expect to see at the museum and what type of people they would be meeting as they explored the various exhibits. Thus was born the What you will see / Who you will meet format. For each exhibit covered on our Web site, the first two FAQs under the category of What to Expect, How to Prepare were consistently, What will I see at Exhibit X? and Who will I meet at Exhibit X? If the visitors read just those two questions and no others, then they would be better prepared to enjoy their visit and ask good questions.

However, the written word can only go so far. Various marketing studies have indicated that the average Web visitor skims text and stays on a Web site only about 5 minutes before jumping somewhere else. (Amy Africa, Creative Results, Wollaston, VT) That's very little time to get even the most basic information across, so images are essential.

TIP #8: A picture speaks a thousand words

On Plimoth Plantation's Web site, pictures literally speak. We decided to highlight the people who work on our diverse sites by having them talk to visitors as if they were really here. For example, on our 1627 Pilgrim Village welcome page (see Figure 2), we show a close-up of a colonial role-player accompanied by a quote in 17th-Century dialect that begins, Welcome to the town. How do you fare.

On our Hobbamock's Homesite welcome page (Figure 2.2), a Wampanoag staff member introduces himself and his culture, speaking in standard English to emphasize that visitors will not be encountering role-players in this part of the museum.

For the Mayflower II welcome page, we feature both a role-player and a modern-day tour guide, to point out that both types of interpretation happen aboard the ship. Finally, on our Nye Barn welcome page, we feature Violet the cow, who welcomes visitors with Mooooo. I am Violet, a milking Devon cow and I live…

Figure 2.1: A friendly face welcomes visitors to the 1627 Pilgrim Village.

Figure 2.2: : A Wampanoag staff member introduces visitors to Hobbamock's Homesite.

The headshots and quotes are an important means of orienting the visitors. They identify the various types of people and the various modes of interpretation visitors will encounter when they visit the museum. These powerful images also help make the Web site more personal, rendering the copious text more manageable and relevant because visitors associate the faces to the facts. Underneath the pictures and quotes, we wrote a one or two paragraph summary of the exhibit and then listed the various categories of FAQs with jump links to the answers.

Working with your Web designers and/or graphic arts staff, you can use a similar headshot–quote–summary–FAQs layout just as effectively in your museum. For an art or science museum, you might consider featuring a curator or educator; for a zoo or aquarium, use the handlers or the animals themselves. These are the faces of your museum, so make sure that they represent your museum accurately. Make sure they smile!

Encouraging good questioning skills and cultural sensitivity in visitors

There is nothing quite so discouraging as asking a crowd full of visitors, 'Does anyone have any questions?' and getting blank stares in return. Sometimes visitors need to be led by the hand to overcome the fear of 'looking stupid' so they can start asking the good questions.

TIP #9: Gear different pages to different audiences

Plimoth Plantation encourages good questioning skills by giving visitors, particularly parents, chaperones, teachers, and the children in their care, various printable Web Guides geared to their needs. We have a Parent's Guide (Fig 3.1) that opens with the statement,

Asking questions is the best way to have a great time! But it can be a bit tricky for children and first-time visitors. Here are hints for asking questions at the different sites…

We begin our Chaperone Guide with 'Chaperones, boy are we glad to see YOU!' and then list fun topics for on-site investigation as well as rules of conduct. The Field Trip Guide explores all these issues in greater depth, with emphasis on cultural sensitivity and the inter-connected history of the Wampanoag People and the English in the 17th Century. At your museum, examine your visitation patterns and see what printable Web guides might be most appropriate for you to write.

Figure 3.1:The Parent's Guide provides parents and first-time visitors with helpful information in a condensed and easily printable form.

TIP #10: Don't be afraid to repeat important topics or culturally sensitive issues

Because cultural sensitivity is so important in shaping the interaction between Native staff and non-Native visitors, we cover this topic over and over again on our Web site. We provide information about appropriate behavior and proper terms to use when talking to our staff, as well as the many common myths about Native People perpetuated by popular culture. This culturally sensitive material is found in the following sections:

- What to Expect, How to Prepare

- Frequently Asked Historical Questions

- Behind-the-Scenes Questions

- Parent's Guide

- Chaperone Guide

- Field Trip Guide

- Plan Your Visit-Cultural Sensitivity

- Kid's Section-Homework Help

- Teacher's Section-Teaching with Respect

Historical Background

While some of the content within these sections is similar, the length, depth and manner in which it is presented reflect who will be reading it and how it will be used. All of the information is clear, concise and firm, but with a gentle touch to assure visitors that we are here to teach them, not judge them. If you have a sensitive topic to cover in your museum, make it easy to find (or rather, unavoidable), easy to print, and easy to understand so that visitors feel comfortable and confident during their museum visit.

TIP #11: Don't be afraid to speak in different voices

Remember that not all those who work at your museum look or think or feel the same way. If you want to encourage visitors to open their minds to new possibilities and challenge their assumptions, then you have to show them the diversity of your staff. Use the general 'museum voice' in addition to other voices, and feature pictures and quotes that reflect the range of perspectives or cultures at your museum. Just take care on every Web page that it is clear who is doing the speaking.

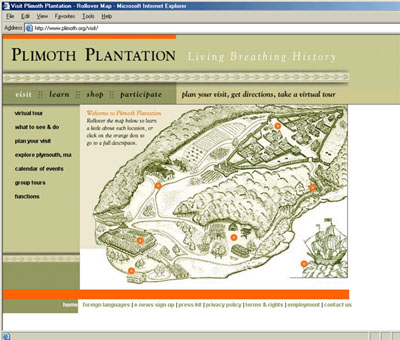

Using Maps, Rollovers And Other Eye-Catching Devices

Museums have long been places where people both learn and play. Web sites should be too. Many visitors will spend more time on your site if you catch their attention and direct their focus towards a map, game or other goal-oriented task. In fact, Plimoth Plantation's new interactive Flash site, You are the Historian (www.plimoth.org/olc) was so successful during our peak season in 2003 that it overloaded our server! In addition to that Flash site, we also have an interactive museum map (Figure 4.1) with rollovers describing each part of the museum, virtual reality pictures of each of our main exhibits (Figure 4.2), and various activities for children, including a 17th-Century dialect lesson, riddles and recipes. These fun features work together to give visitors a sense of the physical space of the museum, enliven the static text and pictures found elsewhere on the site, and reinforce key themes and concepts. Just make sure the devices you employ on your Web site are not simply empty fun, but also further the orientation process.

:Figure 4.1: Plimoth Plantation is a large outdoor and indoor museum with several locations, so this interactive site map gives visitors a sense of the grounds.

Figure 4.2: These IPIX virtual reality images give visitors a 360 degree view of what they will see at the different parts of the museum.

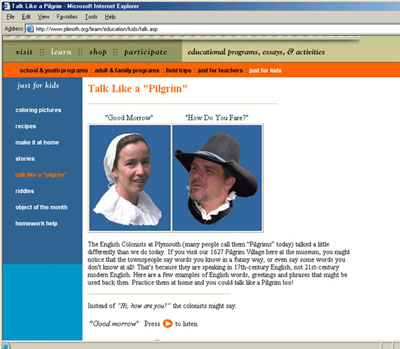

TIP #12: Look to your Education staff for fun ideas

Educators always seem to be chock full of ideas for on-line activities. Maybe it is because they spend their days actively participating and demonstrating a variety of programs with children and the public. Your Education staff knows through trial and error what works in the real world. Sometimes these real-world successes can be translated into the virtual world, although there may be considerable time and expense involved. But many simple games or exercises can remain simple (and cheap) on your Web site as well. For example, Plimoth Plantation's dialect exercise, 'Talk Like a Pilgrim' (Figure 4.3) utilizes sound files of interpreters saying common greetings like 'Good morrow' and 'Fare thee well.' This not only teaches children about the 17th Century, but also helps prepare them to talk to role-players in the 1627 Pilgrim Village.

Web Site Navigation and Design

Plimoth Plantation worked very closely with Brown & Company to assure that all the Web site content would be well organized into an intuitive navigation system. Brown also came up with a beautiful design template that reflected the two cultures we were trying to represent. The combination of clear navigation and the more accurate representation of the museum 'brand' ensures that visitors know what to expect, both on the Web site and on our physical museum site. This parallel is an important one.

TIP #13: To help organize your Web site, make it mirror the real world

At Plimoth Plantation, we decided to organize our Web site around our four main exhibits.

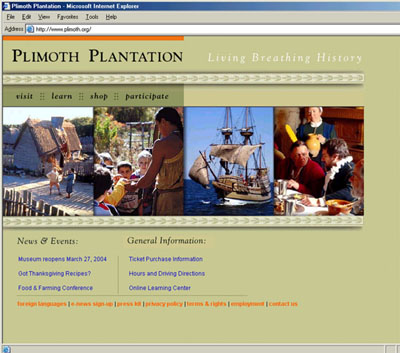

We posted four big, colorful images on our homepage (Figure 5.1) highlighting each exhibit, which then linked to further information. This established entry points or click paths around the Web site that mirrored pathways around our physical site.

We also chose to form four main sections or 'buckets' of information:

- VISIT: Directions, admissions, maps and practical information

- LEARN: Education program listings and historical background essays

- PARTICIPATE: Membership and donation information

- SHOP: Museum shops mail order

Figure 5.1: Plimoth Plantation's homepage highlights four main exhibits: the 1627 Pilgrim Village, Hobbamock's Homesite, Mayflower II, and the indoor exhibit, Thanksgiving: Memory, Myth and Meaning.

These section titles evoke actions and experiences in the real world. Making the virtual world of your Web site mirror real-world processes is just one way to make your Web site more intuitive for visitors. As they move around your Web site, they will come to understand your physical site better too. This is especially important in orienting visitors if you have a large Web site with lots of information to organize and/or a large physical museum with diverse offerings, exhibits or modes of interpretation.

Another museum Web site that uses this virtual=real approach effectively is Mystic Seaport in Mystic, Connecticut, at www.mysticseaport.org/home.htm.

Aligning Web Site Content With Other Museum Orientation Materials and Initiatives

The year 2003 was big for visitor orientation at Plimoth Plantation. Not only did our new Web site launch in October, but a new visitor site map was printed as well, and preparations for a new orientation program began. All these initiatives have different departments and staff members involved, are funded by different sources, and run on different schedules. However, they all share the same goal of orienting visitors better. These various media - Web, print, and video - need to complement each other to get the job done.

TIP #14: Make Web content do double duty

Why write something that has already been written? Or why not share something that is well-written instead of just using it once? As we went through the process of gathering content for the Web site at Plimoth Plantation, we found ourselves having deja vu. Some staff member was always saying, 'Didn't we write that a few years ago?' So we would go digging in the files to find the document in question. Often it would save us some time because it gave the writers a place to begin, even if the final product was completely different from the old document. After all that revising was finished, we often found other uses for the content. For example, the new visitor site map handed out at the ticket desk may strike visitors as very familiar - the same picture and descriptions are used for the Web site's interactive map.

Brief Review of Web Site Statistics and Visitor Feedback

Since Plimoth Plantation's new Web site was launched on October 1, 2003, we have been tracking feedback very carefully to gauge our success. The preliminary results are encouraging. Our Web statistics (Figure 6.1) indicate that more people are visiting our Web site (or visiting more often), and viewing more pages per visit…up 35% over the same time last year! Even though the new Web site was only on-line for 3 months in 2003, it made a significant impact on the overall traffic, up more than 12% over 2002, with over 1.5 million visits recorded. It has also been featured on several tourist Web sites as 'site of the week,' and has been nominated for and won several awards.

Figure 6.1: Preliminary statistics show a marked increase in Web traffic.

For many museum staff members, the abundance of FAQs and orientation materials has made their workday a little easier. Our retail and visitor services employees refer to printouts from the Web site for the most up-to-date information when they are approached by visitors. It also looks as if visitors asked fewer 'bad questions' after the new Web site launched. When I worked as a role-player last year in the Pilgrim Village, not even one person out of the almost 4,000 who visited on Thanksgiving Day asked me if I was preparing for the holiday! One Native interpreter also noted her surprise at not being asked about Thanksgiving at all. Although further research needs to be done to confirm this anecdotal evidence, a lot of breath has already been saved.

In a survey of museum visitors conducted the week of Thanksgiving 2003, all of those who went to the Web site before they visited the museum (70%) found it a useful tool. Over 60% also said that it helped prepare them for their visit, and several commented that the Web site 'made them want to come.' Although some people were confused by the unusual spelling of Plimoth (a perpetual problem), the overall response was overwhelmingly positive. Plimoth Plantation plans to conduct more detailed surveys with a larger sample of visitors this coming year. We hope to build upon our early success and continue to improve the Web site's orientation capabilities.

Conclusion

In addition to advertising programs and providing background information, museum Web sites have great potential to act as electronic tour guides. By identifying the sources of visitor confusion, organizing visitors' frequently asked questions into logical categories, welcoming them with the friendly faces and words of your staff, using maps and rollovers to give them a sense of the physical space, and planning your Web site navigation to reflect the real world, your museum can orient visitors effectively from their own homes. If you coordinate the Web site with other orientation materials to put forward a consistent message, your visitors will become even more comfortable with the information presented to them when they arrive at your door. Comfortable and confident, they will wander your museum exhibits, and I hope, ask the good questions.