|

158 Lee Avenue ph: +1 416-691-2516 info @ archimuse.com Join

our Mailing

List.

published: March 2004 |

Virtual Vs. Physical: Creating On-Line Educational Experiences Through Design

Anne Kaye and Paola Poletto, Design Exchange, Canada

Abstract

This paper examines two Design Exchange programs to explore how we create and present content in the virtual form. The Design Traveller project details the journey from virtual display to physical display while the Electronic Cities project develops a virtual exhibit strategy to compliment an annual festival of digital media design and creativity. Equally important to this study is the developmental journey from virtual to physical exhibition and vice-versa. With the recent completion of two on-line educational products, we explore the nature of the production team and how content and design both contribute to and enhance the learning experiences of the visitor.

Keywords: on-line exhibits, physical exhibits, virtual exhibits, interactive design, on-line education, design history

Introduction

For centuries museums and exhibitions were synonymous with physical spaces in which artifacts were displayed at a safe distance. This paper explores the idea of the new museum: virtual exhibitions, and how we create and present content in this relatively new form. Equally important to this study is the developmental journey from virtual to physical exhibition and vice-versa. With the recent completion of two educational products we explore the nature of the production team and how content and design both contribute to and enhance the learning experiences of the visitor.

Since its inception in 1994, the Design Exchange (DX) has been Canada's design museum and center for design research and education. It is an internationally recognized non-profit organization committed to promoting greater awareness of design, and as well plays an indispensable role in fostering cultural vitality and economic growth. DX is located in the historic former Toronto Stock Exchange building at the heart of the city's financial district. As a medium-sized museum, the building houses 4500 square feet of exhibit space, hosting curated and touring exhibitions based on six design disciplines: industrial, fashion, graphic/new media, interior design, architecture and landscape architecture. The Resource Centre is an additional space for the display of the DX permanent collection of Canadian design, doubling as a study and research library. DX employs a program staff of five people dedicated to the development and implementation of research, exhibition and education activities.

DX has recently created two distinct on-line educational products: Design Traveller (http://www.dx.org/designtraveller) and Electronic Cities (http://www.electroniccities.com). The products share many common elements. Using different approaches, both demonstrate experiences with educational content about design, delivered in a virtual and physical environment.

The two projects illustrate the challenges of developing virtual and physical exhibitions that aim to provide creative educational experiences in design. Experience with these two projects has revealed that the educational expression of design engages students more successfully when the development team is able to bridge the gap between technology and content. In the creation of these two projects, our strategy was to employ the active participation of artists with an interest in popular culture in order to create relevant experiences for the target audience.

Design Exchange and Education

Design theory directly applies to and greatly enriches many facets of the school curriculum, including science, technology, history, social sciences and visual arts. Over the past few years, the DX education department has identified the need for innovative educational materials about design for teachers at the primary, secondary and college/university levels. DX has responded to this need in many ways:

- Students of all ages visit DX to tour exhibitions, take part in workshops and learn first-hand from professionals and educators about applied creativity.

- For many years, DX coordinated a project entitled 'ReDesign', a Web journal about design topics created by high school students for other students. During the four years of the program's life span, we became familiar with youth audiences and discovered their interests and capabilities.

- Designers in the Classroom is a current DX program that matches professional designers with elementary and secondary school classrooms throughout Toronto. The teams work on design projects that implement current curriculum requirements while producing original content for exhibitions at DX.

- The Canadian High School Design Competition, recently transferred to DX from Ottawa's Carleton University, is an opportunity for students to explore their interests in design and create portfolio work for admission to college/university design programs. Students respond to one of five design briefs that require them to explore the design process on their way to solving a specific problem.

Over the years, DX has had a terrific response to these programs and has continued to search for effective ways of bringing these activities to a national and international audience.

Project 1: Design Traveller

The first large-scale educational product created by the Design Exchange was Design Traveller. This project was proposed to Canadian Heritage's Virtual Museum of Canada Investment Program as a way to disseminate Canadian design stories and images to a national audience. The project was approved in June 2002 and an interactive Web site was produced by September 2003. At the time of the on-line launch, DX created a physical exhibition that would transform the Design Traveller environment into a tangible display.

Design Traveller is a bilingual educational Web site highlighting remarkable Canadian-designed objects through a series of historical journeys, interactive activities, and educational resources for students ages 10 – 16 and their teachers. The Web site is a 'fun environment', encouraging students to learn about Canada's history - navigating through text, and artifacts - while engaging in activities and resources that go beyond the Web and into the classroom.

The project's aim is to provide the on-line visitor with engaging, unique and informative activities that position homegrown design as a major influence and presence in the lives of all Canadians. The geographically accessible nature of on-line projects allows the Web site to be used as a current resource and reference guide for libraries, schools and homes across the country.

Figure 1: home page of Design Traveller

Design Traveller is divided into three parts: Game, Gallery and Resources.

For the game and gallery, thirty-five objects from the DX permanent collection were chosen to represent Canadian design from the second half of the twentieth century. The DX collection is the only collection of modern industrial Canadian design in the country, and includes pieces ranging from lamps and chairs to radios and Bar-B-Qs.

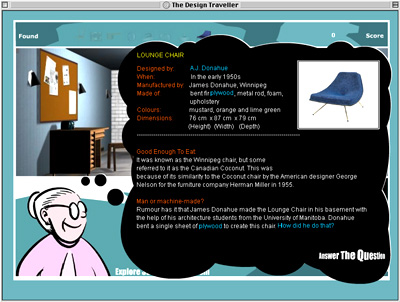

The game component of the site explores the artifacts by decade, from the 1950s to the year 2000. The player is motivated by the challenge of solving a murder mystery that includes a reading-comprehension trivia game (fig.2).

Figure 2: trivia game

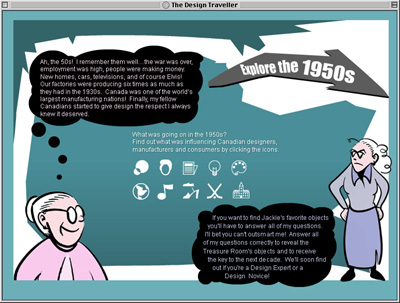

An introduction to each section identifies the mood, styles and historical facts of the decade (fig.3).

Figure 3: The decades

Once the visitor has become familiar with the time period, he/she enters a room designed according to one of the five featured decades (fig.4).

Figure 4: A mystery room

By situating the objects of the DX collection in the decade in which they were designed, visitors are provided with an enhanced perspective on the sociological, political and cultural influences of the time.

Visitors to the site are also offered a variety of unique educational resources that allow them to explore design and the design process on-line and in class. Resources include downloadable lesson plans and word games for in-class use in elementary and secondary schools.

The exhibition that followed the completion of the Website took the virtual environments into the physical realm by transplanting the colour-coded organization of information into staged rooms (fig.5).

Figure 5: a staged room

These 'stages' featured the actual artifacts from the DX collection and inspired a life-like vision of virtual space. The artist/designer that produced the interface of the Web site was invited to work with the exhibit production team to create an easy flow from the look and feel of the on-line experience to the museum's 3D space.

Bringing the historic artifacts into an on-line experience was our first challenge. The second hurdle was transforming the virtual representations of space, style, imagery and navigation into the physical realm. This was achieved by including the presence of the Web site in the exhibit. Computer stations were set up at each stage, and visitors could interact with the virtual rooms while making connections to the actual artifacts in front of them. The bulk of the didactic information was provided on these monitors, while the objects were on display in re-creations of the virtual environment.

Project 2: Electronic Cities

Electronic Cities is an educational Web site based on the content produced for Digifest 2003. Digifest is the Design Exchange's international festival dedicated to interactive art and design. The theme for 2003's four-day festival was Electronic Cities, an exploration of developments in digital media design in reference to the past, present and future of our built environments. The festival featured an international agenda of programmers, designers, architects and artists, who brought their innovative concepts and products to the DX stage.

Before the festival's launch, the Digifest program team put together a strategy to digitize the event's unique content so that it could reach a wider audience. With the support of the Telus New Media E-Learning Fund and Canadian Heritage, DX created an educational Web site targeting high school, college/university students, and life learners.

Both the festival and Web site served as opportunities to reflect on the era of the wired megalopolis in which global communities form and disperse in both real and virtual urban spaces. The content of the festival presentations focused on many 'hot' topics such as augmented realities, emotive architecture, prosthetic aesthetics and warchalking. Audiences discovered how game developers approach virtual urban design and why innovative international architects are designing buildings that think and react.

Figure 6: The Electronic Cities home page

The Electronic Cities Web site (fig. 6) offers an enriched and expanded experience of the geographically specific festival showcase. It benefits our own organizational goals, the exposure and understanding of the work of our featured content producers, and the appetite of untapped design enthusiasts across the country and abroad.

Electronic Cities on-line was launched ten months following the festival. One section of the Web site includes a series of lesson plans that guide teachers and students in the development of new media content on the theme of Electronic Cities. The lesson plans are publicly accessible, offering content by many of the festival presenters in the form of case studies. The other section of the Web site is comprised of a restricted area intended for classroom use. In this environment, classroom assignments are provided for each topic or theme. Assignments range from writing research or reflective papers to creating graphic and animated visualizations. Teachers control their on-line classroom and are able to grade the assignments that their students upload to the site. Once the work is complete, the work can be posted to an on-line community gallery.

The Electronic Cities Web site provides current and unique resources, including video presentations, texts, and documented visual art works. These kinds of materials are rare and difficult to deliver in a form that is accessible to educators and students. For this reason, every attempt was made to take sophisticated ideas and interpret them in a format that is easy to read and understand.

The combination of the Electronic Cities festival and Web site was conceived as a programming model for the delivery and translation of high quality content to every Canadian classroom. Above all, it strives to encourage and inspire our young designers of the future.

Physical vs. Virtual

DX projects are often bound by the physical and spatial qualities of design itself, whether expressed as place through architecture, landscape architecture or interior design; or as products produced by industrial, fashion or graphic designers. The use of new media tools in these design disciplines has altered not only production and delivery methods in all fields, but also the face of design entirely. The impact of new digital tools on design, for instance, becomes apparent in the new generation of designers who premiered their work at Digifest. Their methodologies and their content are as innovative as the tools they use. The new design landscape has become one that blurs the lines between physical and virtual representation.

The possibilities and realities presented at Digifest represent variations of augmented reality, where physical spaces are literally augmented by real-time virtual realities. The DX has responded to this exciting new landscape by focusing on the relationships and strengths of designing physical and virtual programs as a complete programming package.

Both Design Traveller and Electronic Cities employed a design vision that would attract and sustain a very targeted audience. Design played a key role in the development of these projects and an even bigger part in the development of their transformations from physical to virtual and vice-versa.

The Electronic Cities Web site served several purposes. The main goal was to document the proceedings of the festival for a wider audience and create a product that was organized in a format resembling an on-line exhibition and educational resource. The process of documentation led to the development of a product that would offer some interaction with the transcribed material. Going beyond the simple question-answer period at the end of festival presentations, the visitor explores the material, digests it, and is then challenged (by working on the assignments) to become a critic of information or a digital media creator. Both the Web site and the festival offer a basis for different visitor experiences. Each medium has its own identity while being built around the same core content. The resulting package makes for a richer and more integrated experience that satisfies a range of visitor interests.

The transition from festival to Web site was facilitated by having two of the Digifest presenters involved with the design: Marc Ngui, cartoon artist/architect, and Duro3, graffiti artist/Web/graphic designer. Ngui and Duro3 are both close to the pulse of popular street culture and were immediately identified as partners on the Web site's development. Having had first hand experience of the voice and feel of the festival, these artists/designers were able to help tackle the transformation of the physical experience into a virtual one. It was essential that Electronic Cities' on-line incarnation be attractive to its target audience of 16 to 25 year olds. By creating a mix of hip design and playful iconography, the site caters to the aesthetic sensibilities of the target audience.

The Design Traveller Web site and exhibition was a similar journey of physical/virtual transformation, albeit traveling in the opposite direction. The transformation can even be described in two stages: from physical to virtual and virtual to physical. The content from DX archives and the artifacts from the permanent collection were modeled in digital 3D for the Web site, marking the first journey from physical to virtual. Once the virtual environment was complete, the content and design were interpreted for the physical exhibition.

Close to the beginning of the Design Traveller project, it was necessary to identify a designer who could create a virtual space that targeted the adolescent visitor without presenting a juvenile image. The design was headed by Duro3 just as he was beginning his relationship with Digifest. As a celebrated graffiti artist, Duro3 was able to infuse the Web interface with an energy not usually associated with the didactic nature of museum exhibitions. Unexpected shapes and lively colours cater to an audience that is familiar with playing video games.

The exhibition was aimed at a similar audience, but an effort was made to avoid alienating the other visitor groups. A multi-media approach was developed to utilize the strengths of both the virtual and physical media. Elements of the virtual were brought into the exhibit to promote the Web site and notify the visitor of a value added experience online. Duro3 was brought in to recreate his shards of colour on the floors and walls of the exhibit space. The 3D models of the virtual rooms were made into slides that were projected on the walls. These projections set the stage for the actual collection objects that were placed in front of their modeled counterparts in the projections. The result was a dramatic use of light and shadow that bridged the gap between physical and virtual representation.

Figure 7: the virtual and the physical

Computer stations (fig.7) next to each stage contributed to the sense of a virtual exhibit within the physical one. For the most part, the exhibition appealed to student visitors. Reviews from adults proved more complex as some welcomed the interactive computer stations and slide projections, while others were uncomfortable with artifacts sharing space with computer stations.

The experience of working on the Design Traveller and Electronic Cities projects was a turning point for the DX programming team. The opportunity to create on-line educational experiences increased the value of DX museum and education programs. For a medium sized museum with limited physical space, the virtual world provided the 'square footage' needed to deliver this type of complete-package programming.

Aura vs. Information

Many of the speakers at Digifest were exploring the idea of the physical and the virtual within their own work. Sabine Himmelsbach of the ZKM Museum in Germany delivered the festival's keynote address. In an essay prepared for the festival program entitled Virtualization of the Metropolis, she describes a world that is divided into information 'haves' and 'have-nots'. Himmelsbach, along with forty featured presenters, ranging from game designers, architects, hackers, graphic designers and design managers, illustrated in a range of ways how the economic and social capital of on-line information is still integrally - albeit interchangeably -connected to the design, delivery, adoption and consumption of physical spaces. The networks between the physical and the virtual seem more common and natural today. This is especially the case for the target audiences of our on-line projects.

Information 'haves' and 'have-nots' offer an intriguing relationship to the ideas that were put forward by Reesa Greenberg in her recent paper, Editing the Image: Museums and the Web, presented at the University of Toronto's Editing (Out?) The Image Conference (Fall 2003). Referring to an exhibition of the works of Frida Kahlo, produced by The Jewish Museum in New York, Greenberg illustrated how the on-line exhibition served the primary purpose of delivering information about the artworks, while the physical exhibition focused on the creation and the support of an aura about the artist and her work. Greenberg suggests a correlation between virtual exhibition and physical exhibition, and information and aura. Within a physical exhibition, a painting's aura is established by providing ample, unhindered space around the artwork, while in an on-line display, a painting's significance is established using abundant textual information.

In the Design Traveller project, we begin to see a breakdown in the assumption that aura is solely connected to physical representation. While it is true that the basis for establishing a collection of Canadian industrial design objects is to support and celebrate the essence of national design, each object in the collection is thus circumscribed with its own distinct aura by virtue of being collected and housed at DX. However, in the Design Traveller physical exhibition, a virtual tableau is created not only to support, but to potentially undermine the object's value. The actual objects of the collection appear within a veiled shadow of colour - an image projection of the virtual room veils every object so that it becomes an integral part of the virtual tableau (the 3D environment is projected to human scale). (See figure 2). The aura of the object is underwritten by the tableau itself, which is standing in as a virtual representation of the on-line virtual representation. This effect is further augmented by the contributions of Duro3, a graffiti artist and graphic illustrator for both the Design Traveller and Electronic Cities Web sites. Duro3 recreates the Design Traveller's graphic elements for the physical exhibition. What the viewers experience is a simulation of the on-line virtual environment. The response is mixed. Viewers expect aura from a physical exhibition. They do not expect to see objects stripped of their aura to be delivered as pure information, risking redundancy. They do not want shadowed silhouettes, even if they are created by colourful projection screens.

From a different perspective, student visitors, an audience typically less interested in static exhibitions, were fascinated with an exhibit that played with perception and involved complex visual information for the shortest of attention spans. Students were eager to jump from computer to computer either before or after exploring the artifacts on 'stage'. The effect of using interactive elements within the exhibit space served this particular audience by catering to more contemporary ways of learning.

Surprisingly, in the Design Traveller Web site, the 3D game environment creates an aura - not around any one object - but rather around a series of lost decades. It is tied to nostalgia. The information about the objects is supported by trivia about our past. It responds to a fascination with retro-culture. Here, the strategic use of secondary information and 3D technology within an immersive game environment creates a support for the objects and an attempt to reestablish aura within a virtual set.

Within the context of our Electronic Cities project, keynote speaker Sabine Himmelsbach's picture of the telepolis and Greenberg's understanding of the complex nature of the real and the virtual exhibition space are poignant and potentially interchangeable ideas. For example, Himmelsbach's insights about the city as a metaphor for our virtual spaces resonate with the museum experience or exhibition described by Greenberg. Himmelsbach states:

Today, cities are partially defined by their virtual urban spaces, which radically alter the image of the city itself. The telepolis as metropolis of the future can never replace the real, experiential world, but it can offer its inhabitants enriched and expanded potentials.

When we think of targeting museums to larger audiences, we have grown accustomed to migrating the physical exhibition experience to an on-line experience. We have still larger leaps to make when we begin to bring our virtual urban spaces into our museums. We could apply Himmelsbach's statement about virtual and physical cities to museums:

Today, exhibitions are partially defined by their virtual urban spaces, which radically alter the image of the exhibition itself. The virtual exhibition as physical exhibition of the future can never replace the real, experiential world, but it can offer its inhabitants enriched and expanded potentials.

The Electronic Cities and Design Traveller Web sites offer something more by providing tools that are unique to the medium, thus escaping direct comparisons to physical exhibitions. Both provide interactive involvement with content that targets the evolving nature of audiences.

Art Direction and Design - Team Perspectives

Art direction and design played a large role in the development of the Design Traveller and Electronic Cities projects, in terms of both content and layout/exhibit design. Here we ask the content developer of Electronic Cities and the designer on both projects to reflect on their experiences throughout production.

John Sobol

As co-director of Digifest, and co-producer of the Electronic Cities Web site, John Sobol developed and wrote twenty case studies for Electronic Cities. John responds to three questions regarding the artistic vision and creative experiences throughout production. Questions are in italics.

What was your experience working with both a graffiti artist and a comic artist in the development of the Electronic Cities Web site? How would this differ from working with a graphic designer? Do you think this choice impacts user response?

The experience was different than working with most designers because the two artists tackled the design problem with a more pronounced expectation of finding a solution that was based on a personal and idiosyncratic style. Their work affects user response because there is more to grab onto - more of a raw personality and less slick faddish design.

Can you describe your experience of putting content presented by designers and artists at the festival into an on-line educational context that is aimed at an audience demographically younger (secondary and post-secondary school level) than the festival-goers (25 years +).

This was a very satisfying experience for me as I very much enjoy creating educational content. I find it very satisfying and empowering to present challenging and provocative ideas and work to young minds in a constructive context.

Can you briefly describe the aim of Electronic Cities and the challenges of producing and distributing an e-learning Web site.

The aim of the Web site is to create a catalytic and inspiring context in which students can produce experiential learning projects. They can use case studies that document technological innovations as jumping off points for developing meaningful local narratives about life in the electronic city.

The main challenge in distribution is that the dominant educational infrastructure does not reflect the cultural landscape and educational imperatives of teenage life today. Consequently, a useful and well-designed learning resource is incompatible with the teaching methodologies used in most classrooms and by most teachers. Moreover, the e-learning industry in Canada suffers from a disastrous disengagement on the part of both the public sector (i.e. School boards) and private sector (especially ISPs, cablecos and telcos).

Sobol's main challenge was to transform content for a younger and less experienced audience. It was essential to ensure that wording, sentence structure and presentation were accessible to the visitor. It was also important to investigate curriculum guidelines in order to create a product that could be easily used and marketed to a school audience. Much of the content included complex ideas and new terminology that had to be translated into more simplified language.

Sobol discusses the struggles that are faced by educational Web site producers when their product is ready for school use. Marketing opportunities are slowed down due to the relative unfamiliarity with the medium (Internet) as a source for educational resources that go beyond simple reference. Teachers do not yet seem to have confidence in the value of on-line material as they would with textbooks. By providing these materials from a recognized institution, both Design Traveller and Electronic Cities have a better chance at reassuring teachers of the reliability and value of the information being presented. As more educational virtual projects are produced (many are supported by Canadian Heritage's Virtual Museum of Canada Investment Program, http://www.virtualmuseum.ca), teachers may become more comfortable utilizing these rich sources of Canadian and international educational content.

Duro3

Duro3, a.k.a. Arturo Parada, is a Canadian graffiti muralist whose innovative 3D style has influenced aerosol artists around the world. His organic and fluid graffiti style has profoundly influenced his idiosyncratic and widely respected Web design style. Duro3 premiered his new creation Pod at Digifest 2003 and designed the visual identity of both the Design Traveller and Electronic Cities Web sites. He extended his involvement with the Design Traveller project by participating in the production design of the exhibition.

An interview with Duro3, conducted in the middle of the installation of the Design Traveller exhibition, reveals his enthusiasm for crossing over from virtual to physical and vice-versa, while using both as a forum for unbridled creativity.

How did you come about being involved with the Design Traveller project?

I met the co-curator of Digifest at a graffiti symposium and that led to my presentation and collaborative work for Digifest. The next project that came about was Design Traveller. I was brought in to do a remix of the initial design of the Web site. I didn't know that the Web site would be turned into a big installation in the museum. I was brought in to create some elements in the exhibit - on the floor and the walls - and make it look like the Web site. The style was based on a fractal design, abstract elements, different shapes and patterns that create movement around the space.

I know when you work, you're always surrounded by your entourage - what do you call them?My crew?

Can you talk about how that works? What are the dynamics of “the crew”?

Well, I was taught graffiti by my cousin and it's something that's been going on throughout the ages - that teacher-student relationship. So I started teaching some other people including my friend Water - he ended up doing great work on the project for Digifest - I think it's very important to be surrounded by other creative minds. You teach someone something and they come back and teach you something.

Would you bring your friends here?

Oh, for sure, I would tell everyone that I was working here and they would be impressed.

I think that people of my generation don't go to museums that much. I hoped that we could change that with this project.

Would they look at the work that you've done on the Web site? Is that something that is more accessible than a museum?

I think nowadays the internet has enabled so much. People don't have to go to the museum at all. It's actually good and maybe a bit bad. Maybe now they won't leave their houses anymore! They can just sit at home and visit the artifacts.

But by being here in the exhibit, I discovered that I had no idea how much Canadians have contributed to design. I've seen a lot of these things before, but I didn't realize that they were designed by Canadians. I definitely learned something by the end of this project. That was a really cool experience to take a lot of new information from the content.

Do you like working with projects that will actually be used in the classroom?

Ya, that's amazing. I feel like I'm helping out kids that are not necessarily interested in studying. I helped create an artistic environment for the historic information.

How do you identify yourself? As an artist, a designer, or a programmer?

Right now I think people would consider me a Web designer, muralist, a graphic designer, but me personally I just want to be like Leonardo Da Vinci in the end – on a constant journey of creativity.

Duro3 discusses how he has benefited from working on the projects. As a designer, he found that he was learning as he worked with the team. The collaborative nature of these projects is in tune with his own working philosophy. Duro3 works with many young designers at the beginning of their careers and is able to keep abreast of what engages youth. He is aware of their interests and acknowledges their apparent lack of interest in visiting museums. He believes that they are the ideal audience to benefit from on-line exhibitions and that these Web sites could drive attendance to the museums themselves.

Conclusion

DX has a small but dynamic staff who continuously seek to program relevant projects that will increase the museum's ability to showcase and celebrate Canadian design locally, nationally, and internationally. As a small team, we seek new ways of balancing relevancy and celebration with resourcefulness and audience impact.

Our on-line exhibition projects have permitted us to explore ways of broadening our local audiences. We have explored how a virtual exhibition space may contribute to our more traditional programming activities. We have learned that displaying greater amounts of information about artifacts through the use of digital media tools within an exhibit space can be advantageous in reaching a wider, younger audience. We have also gained valuable research information in regards to the relationship between aura and physical or virtual representation of artifacts and ideas. The presence of aura within an on-line exhibition points to the potential of reaching museum enthusiasts on-line.

The Design Traveller and Electronic Cities projects have demonstrated that our collaborations with artists and designers not only bring unique stylistic elements to our museum programs, but also often attract younger audiences who share a kindred knowledge of sophisticated digital media skills.

DX initiatives aim to apply current design and museum practices. Our physical and virtual spaces are inevitably linked and when they are explored together, they provide rich, multi-layered museum experiences. The blurring of virtual and physical offers us an exciting opportunity to critically discover new models for museum representation.

Acknowledgements

We wish the thank Samantha Sannella and Elise Hodson for their help in editing this paper. Appreciation goes to John Sobol and Arturo Parada for sharing their experiences with these projects.