|

158 Lee Avenue ph: +1 416-691-2516 info @ archimuse.com Join

our Mailing

List.

published: March 2004 |

Digitising African Oral Narratives In A Global Arena

Renate Meyer, Centre for Popular Memory, UCT, South Africa

Abstract

While technological advances provide new preservation and dissemination practices for African archives, they rely largely on internationally developed standards for digitisation and prioritisation of material. What that means is African concerns relating to Intellectual Property, community property and access to technology, as well as connection to global forums, are largely ignored: technology is controlled by trans-national organizations off the African continent. Issues such as ‘global homogeny’ focus the world on the West - its practices, icons and language. Multi-lingualism for Web-based media and digitisation/ transcription procedures for languages other than English remain under-developed and under-prioritised. In short, there are concerns that are specific to the African continent which are not being addressed on a global level. Through the Centre for Popular Memory’s (CPM’s) audio visual archive and the collection of narratives of urban terror and power relations in the diasporas, these concerns are explored with relation to digitisation procedures, storage mediums/customised digital repositories, and virtual archives in a global context.

Keywords: South Africa, digitization, oral history, archives, globalization

Introduction

South Africa is an interesting place: it lies on the southern tip of Africa and yet is seen to be central to Africa’s ‘renaissance’. It is one of the youngest democracies in Africa, but holds the power to lead the 53 countries on the continent forward. It has one of the most liberal constitutions in the world, set in place by a former prisoner, Nelson Mandela. It is a country of 9 provinces, 11 official languages and 44 million people affected by previous racist legislation but now acting as one nation. While colonial visions of lions running through the streets being chased by people with spears are hopefully being altered with the global environment, Africa is receiving a new fracturing in being left behind in the technological ‘revolution’ that is structuring the world with its servers, domains, (wireless) cabling and software.

In this paper I intend to concentrate on the following questions:

- What is the current African situation with regard to ICT’s?

- What are the positions of South African archives/museums-globally?

- What does the Centre for Popular Memory actually do?

- Looking in the digital crystal ball, what does the immediate future hold?

The Current Situation For Africa

In exploring my theme of Africa’s relation globally with regard to digital representation, let me start with mapping the current situation with regard to ICT. I will be using South Africa as a case in point - as it is not only the country I represent, but also one that, due to the racialised nature of its economy and the legacy of Apartheid, has a ‘dualistic economy and society that has elements of both a developed and developing country’ (Adeya, Cogburn 2002). Also, South Africa relies on its relationship with the world economy for about 50% of its GDP (Davies, 2004), and so isolating ourselves could only be implemented at huge cost. We have also learned some valuable lessons with regard to S.A’s position in the world economy. The country produces less than half a per cent of the world’s GDP, and so it is the current government’s view that SA will not be one of the “losers’ on the globalization scale. For government officials, the key to being effective in international forums is creating partnerships - such as NEPAD and wider South / South collaborations. This is coupled with a number of other factors that make it an interesting case study. Some of those factors include current government policy that involves large investment in ICT. For instance, in 1999, ICT expenditure in SA was at 7.2% , higher than the world average of 6.6% and higher than high-profile countries like Japan, Ireland, Denmark and Malaysia (Digital Planet, 2000).

South Africa has a relatively sophisticated technology network. We have ISDN (Integrated Services Digital Network), GSM, video conferencing and WAP. Also, according to Adeya and Cogburn, South Africa’s GSM Cellular network is the ‘largest in the world outside of Europe and the percentages of digital switches is higher in SA than in many industrialized countries’ (p18). Our computing infrastructure has increased dramatically since 1992 when the number of installed PCs was just over five hundred thousand. By 1999, over 3 million were in use. Of those, 65 % are networked, and SA is ranked 17th in the world regarding Internet host computers. According to netsizer.com the penetration of Internet in SA is 30 times that of Egypt, its nearest competitor in Africa. There are over 75 Internet service providers, 100 cities with local Points of Presence (POPs) and an estimated on-line population of 650,000 dial-up subscribers. Considering the statistics that suggest the on-line population for the whole of Africa is estimated at 3.4 million, SA holds a considerable part of the pie.

While these figures statistically reflect very well on South Africa, they need to be understood in context of the country and continent. The percentage of SA households with telephone lines, 31%, sounds promising when compared to 19% in China or India, but pales when compared with the USA at 92% or Denmark at 143%.

The most important feature that is missing is distribution amongst the population. So while SA has a population of 43 million, previous regimes have skewed distribution and access to training and technology within that population. Prior to the 1990’s, only 13% of South Africans, basically the white population of South Africa, had access to many information and communication technologies and skills.

But since 1996, SA has drawn up rigorous e-commerce (Green Paper on e- Commerce) and ICT policies. Since the change to democratic leadership in 1994, key government officials have tended to harness the potential of the digital economy and information age. In the words of the S.A Minister of Arts and Culture,

We (SA) believe that the ‘next wave’ technologies can ultimately create an impact in both developing and developed societies, which can promote global appreciation of technology for constructive business exchange and economic growth for all. (Ngubane, 2002)

Leaving the statistics, I will briefly explain what it actually looks like on the ground. Remember that SA is geographically large in proportion to its population. One example we like touting is that the entire United Kingdom can fit geographically into our national game reserve- the Kruger National Park. Of course, in response, the Americans say the whole of South Africa is roughly the size of Texas, so I guess it is relative!

From the ground, SA’s major cities and even smaller towns are fairly well connected virtually. You can easily access any number of Internet café’s in the cities, and both land lines and cellular communication are stable and comprehensive. If you walk along the streets in the urban centers, it seems that everyone, from the newspaper seller at the street corner to the shop owner, has a mobile phone, but the substantial use of cellular communication is not necessarily a symbol of affluence. Cellular contracts and pre-paid systems mean that for about R 60 (about 8 dollars) a month, a person can afford to own a mobile phone. It is seen to be a very worthwhile acquisition as often many family members occupy a small house, frequently having only one room. Within the townships, a mobile phone offers the opportunity of, on the one hand being available directly 24 hours a day, and on the other affording the status of upward mobility.

While up until the 1990’s, schools were racially divided, this is no longer so, and scholars (in the urban centers) now all have access to computer training and Internet facilities at their schools. Of course, there is still a huge backlog with regard to the generations preceding the current group of learners, but the government has employed a number of strategiess to try to rectify the problem.

It seems then that while the infrastructure has been ‘folded out,’ the largest challenge is actually in the form of human capabilities. SA shows a severe shortage of people with the necessary skills to harness the ICT industry. According to Statistics SA, this is exacerbated by widespread emigration of skilled South Africans: 77% of emigrants have tertiary education.

While access to personal computers is still low in the township areas (and obviously the rural areas of SA), government operators such as Telkom and the Post office are placing public Internet terminals in places where communities gather. This, coupled with telecentres, comes close to addressing SA’s universal access goals (Adeya, Cogburn:2002). According to the Department of Communications, 90% of SA households are within 30 minutes’ walk of a telephone or telecentre.

From this macro overview I want to look now at how that relates to the world of museums and archives in this country.

South African Archives And Museums’ Global Positions

In the 1970’s, provincial and government-run museums became very popular in South Africa, and almost every national, provincial and local government department or enterprise had a museum section. Of course, these structures were very oriented toward a white South African audience. Thus representation and subject matter were very skewed. This legacy has left a large representation of public and private museums and galleries throughout the country, although often these museums represent an exclusionary past as opposed to a public intervention or access space. It is not in the scope of this paper to explore them systematically, but I would like to highlight a few factors. Most, if not all, museums and archives have relatively small and complex budgets; on a government level, funding has been slashed over the last few years, with the cultural budget taking a large knock.

But at the same time, there is often understanding of the importance of international collaboration and trade. One example is the Cape Town International Convention Centre (CTICC) that is aimed at encouraging international conferencing and cultural interaction. In line with this understanding of the importance of international tourism, there is a growing representation of international brand hotels such as the Sheraton and Hyatt, and more urban hotels are providing digital communication centers and Internet ports in hotel rooms in line with the growing need to be globally connected.

More important, most government institutions, cultural and otherwise, are available on the Web and have digital connectivity amongst user groups/ education forums and listserves. But the level of Web presence is what is interesting. As the majority of museum sites are done using basic, servers tend to be slow and images cumbersome. Search facilities within these sites are also not comprehensive nor user friendly; thus the access the site provides only acts as a type of ‘on-line brochure’ rather than harnessing the World Wide Web’s capacities. This leads me into my third area: What does the centre for popular memory actually do?

The Centre for Popular Memory

Based at the University of Cape Town, the C.P.M is essentially a public service archive and resource center. It has four main areas of work: research, training, archiving and dissemination: dissemination is at the core. These streams are all inter-related. For instance, in 2002, we trained students who were selected from an associated postgraduate course: the Post Graduate Diploma in Museum and Heritage Studies. Over a nine-month period we taught the three interns skills around oral history interviewing, transcription, archiving, and exhibition design. During the internship they chose a theme for their practical interviews and recordings. They each chose to conduct 20 interviews with long-term residents of Langa, concentrating on the residents’ memories and stories of shebeens and the alcohol trade between 1930-1980.

Black people weren’t allowed to have shebeens. They were raided, arrested and paid fines. They couldn’t even enter bottlestores or stand near a bottlestore. They weren’t allowed to deal in liquor or buy liquor. It is only in the 1960’s that black people were allowed to enter bottlestores.

Ms PM (Audio 1: Ms PM WAV. File)

Until 1962, black people in South Africa were not allowed to consume or buy alcohol, or even make traditional beer (umqomboti) without a permit. Yet people drank and smuggled alcohol into the townships, and the shebeens (which were often no more than a chair at a kitchen table) became places of recreation and resistance. One of the points that was often raised in interviews was that most shebeens were run by women:

Yes, they managed to survive, I am telling you… the shebeens had to survive. One wouldn’t have liked to be a shebeen queen, but though one thing, you will find…Here is the lady, she has got about 4 children that are at school, what must she do? So, to survive you know, she had to sort of do it illegally [sell liquor] so that she can make ends meet.

Mr M. (Audio 2: Mr M WAV file)

What is significant (for this paper) is that the information that came out of the research, as often happens, is very different from any written textual accounts of the era described. So the research provided an alternate view of how the history of that time was presented. While this paper does not explore these complexities, it serves to highlight that stories provide invaluable material regarding what people remember and forget about living in that country. What were/are conditions like? What were the experiences and memories of that time? How do they relate to other people’s experiences? and so on.

We completed the process with close to 60 interviews conducted in English and Xhosa with residents of Langa. These recordings are all transcribed and translated and the images, artefacts and interviews are archived. Our concern is that the research not just sit in our archives and get indexed into our digital repository. If we are to have a social purpose, the stories that we record need to go out into the world.

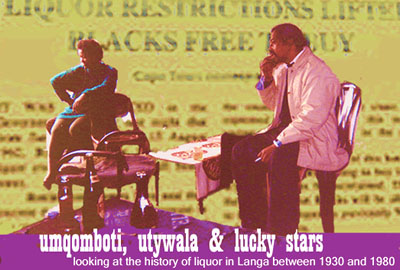

For this collection, we decided to create Umqomboti, Utywala and lucky stars – People’s Stories Of Liquor In Langa Between 1930 And 1980, an exhibition and audio CD.

Figure 1: Umqomboti exhibition

The idea behind having a movable exhibition was that it could alter with space available and conditions, but most important, the research would go beyond the archival stacks. For more information regarding the exhibition and ‘shebeen’ research, visit our Web site www.popularmemory.org.

Living Archives

Derrida in his book Archive Fever (1995) demonstrates that the archival trace implies both process (its power) and place. In postmodern terms this control of process and place is partially what archiving entails. Another issue that Freud and Iriguray draw on is the instinct to forgetfulness. In Freudian terms the notion of forgetfulness cannot be separated from processes of memorialisation. So, then, the archive has a lot to do with knowledge and power, and is about remembering and forgetting at the same time. To expand the notion, Harris notes,

The archive seems to draw us forward as we look to the past…the idea is not to concretise memory and create fact…but to acknowledge that fact is contextual and disturbed by what is left or forgotten or gathered and not gathered. (Harris: 2000).

The archive cannot be viewed as a neutral space where records (or archival traces) are stored. In Post-modern terms the archive is a construction, and archivists are responsible players in this construction. The relevance this has is that theory informs practice. The recording has a life of its own; it not only is given meaning through the process of archiving, but also can gain meaning through historical/sociological and ideological debates and contexts.

This acceptance of the subjectivity and active participation of the archivist and archive in the process of production further suggests that we need to play active roles in getting the stories we have in our archive into the communities we serve. For us at the CPM, that doesn’t mean just making the archive accessible through an effective catalogue system, digital database on the Web or simply an open door. It means finding ways to step out of our doors.

To do that, we must confront intellectual property issues, copyright issues, and legal issues. The line we take is quite simple. Our first step is establishing and not breaking trust with interviewees, so that they feel comfortable and protected. The second is ensuring that their wishes are legally ratified, through our copyright release form. Third, even if we have copyright on the material, we have an ethical responsibility to use it in a sensitive, contextual and reverent manner.

Much effort goes into the recordings and correct archival procedure, but that is not enough. Expanding audiences and negotiating difficulties also lie at the heart of a useful A/V Archive. I know that in South Africa, and I don’t believe it’s confined to there, archives are not seen as being the most inviting places: they are often frequented only by tenacious researchers and students trying to complete last-minute assignments. But we need to change the notions of both what the archive or museum does and what it holds. After all, we hold people’s stories, and surely those stories belong beyond our temperature-controlled vaults.

To do that we need legal copyright forms and understanding from interviewees as to what we are doing with their recordings. Also, due to the nature of A/V archiving, we need to follow migration/preservation strategies. In our case, many of our older recordings are on analogue cassettes; we digitise them to 96/24 data, which are stored as multiple copies across multiple media in different locations. We also enter all the recording metadata information into a digital repository and hold electronic copies of all sound clips, transcriptions and translations.

But while the bits and bites of our technical jargon are essential to us, we need to remember what we are working with. While we can get immersed in building cyber architecture and discussing which cartridge stylus provides the most accurate rotation (or is it revolution?), we also need to keep in mind that those digital 1 and 0’s and the subsequent metadata hold the voice of a person. We all understand the importance of our senses, being able to speak, be heard and be seen. In the same way the archive needs to work more cohesively by not only providing text transcripts, but also allowing users to listen to the sounds, read the quotes, connect the pictures and, through this layered process, make interpretations.

One of the uses of having a digital version of an analogue or physical trace is that it means access is increased while the original is protected. As such, digital technology suggests a desire to communicate - to create ways of using, sharing and accessing information. It provides the platform to start exploring those desires. While all that is international practice, what differs is the relation to signs and signifiers that are the Internet. There is still a vast portion of South Africans who are not computer literate, and there is a further issue that while English is one of South Africa’s 11 official languages, it is not the first language of the majority of the population.

We believe that even if a group constitutes only an almost invisible fragment of the world population, there should be at least access for them to first language narratives and transcripts on-line.

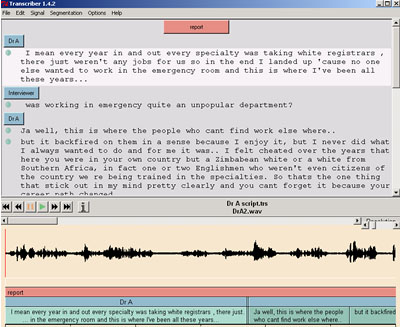

Figure 2: Screen shot- Langa sonic gallery-Xhosa narrative

Figure 3. Screen shot: Transcriber

Virtual Archives

We are developing a partnership with a project that is working in Brazil, Namibia and South Africa. A virtual archive is being developed, available through our center, navigated using gaming technology. So language is not isolating but unifying for people who are not used to Internet/ archive navigation techniques.

The Threat of Cultural Imperialism

There is a growing concern regarding the use of African content in worldwide forums. The most radical or conservative of them is ‘cultural imperialism’ (Henriot, 1998) driving new technologies and the ‘McWorld’ of MacDonalds, Macintosh and MTV. There is a view that Africa is being recolonised in the virtual environment, as international technology partners are looking to provide technical expertise for the “globalizing” of African content. African partners for the most part do not control the servers/ programmes or technology that houses their content.

There are further concerns over Intellectual Property and community property of African songs, narratives and content management. This is something that lies both within the continent and without. There are partners that have funding and others that do not. What has happened in the past is that funded (African) partners go into rural areas to record traditional narratives, but never return those rights to the community. This is not confined to visual culture, as Indigenous Knowledge Systems (IKS) are being recorded or networked and then patented outside of the community that traditionally used them. To use an example, the Khoi San people have a mixture of roots they use to suppress hunger while they are hunting (since they hunt with a poisoned arrow in the desert, they can track spoor for days before even seeing a buck). This combination is now being packaged and traded to the international slimming market, which as you know is huge! There is currently an investigation into this product, and until the rights and IKS issues have been secured, it has been withdrawn from the market. I think this is one of the largest fears within the traditional groupings around the world: that technologically advanced and moneyed groups, however altruistic their original aims, will hold the rights to another community’s content.

Just for the record, I along with many other forward- minded people see the possibility and accept the responsibility of international partnerships and digital representation. I would rather be forging paths through the I.P haze of the digital domain than closing the stories in our archive out of fear. Take a look at our partnership with Matrix at MSU in the next and final section.

The Digital Crystal Ball - The Immediate Future

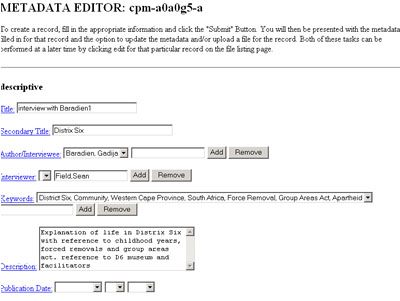

Conway (1997) suggests, “the biggest challenge may not be embracing digital technology, but rather building a common language to describe the transformations that […] take place”. One way to protect traces in the digital domain is using metadata, as that is the way our new digital trace is recognizable over time. For us it includes different sectors:

- Descriptive metadata - referring to the trace and the description thereof – title, collection, interviewee, interviewer, date of interview, location etc

- Technical metadata - referring to the digitisation process and its description - i.e. file format, bit rate depth, size, duration, compression

- Structural metadata - how to reassemble the trace-

- Source information - audio analogue cassette, photograph, and physical description

- Rights and restrictions - copyright holder, copyrights, distribution restrictions

For us, metadata is about creating a common Underground for the accessing and migrating of digital information. It is imperative that the entered data fulfil a number of functions. For one thing, it must be compliant with terms discussed through initiatives such as the Dublin Core, METS and ILAC.

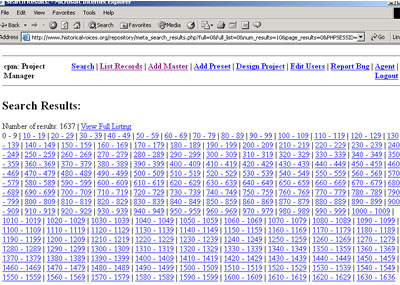

Metadata repositories can be created anywhere in the world and ported through FTP (file transfer protocol) - so you can enter information at one station and have it immediately available to anyone who has access to that repository. In our case, we are looking to have the software on a local drive. In that way we can provide localised searches, both from within our resource centre and globally through our server and the space we occupy on our partners’ servers in Michigan.

Figure 4. Screen Shot ‘Repos’

Figure 4b. ‘Repos’ defined

By September this year, ‘repos.’ (as our American partners like to call it), which is currently serving as a metadata back end, will be on-line and user friendly. The aim is that through the interface, users can access CPM holdings on-line. We are including all copyrighted material we have; they will be able to do detailed searches that will bring them to a page with all relevant information: sound clips in the original language, text transcript in pdf, translations, related images and background information. This will all be immediately downloadable and comprehensive.

Conclusion

Africa is a continent both near to and far from technological stability. Through well-constituted partnerships and intelligent and proactive methods extending from the continent, there are ways for technology to be harnessed for our purposes, not the other way around. At the Centre for Popular Memory, our primary aim is the dissemination of people’s stories under conditions that are stable and founded on integrity. For us there are global ways to do this. And there are also ways for us as archivists, technicians and cultural activists to walk outside our doors and engage with the communities we serve in multiple ways.

Acknowledgements

All interviews quoted in this paper are housed at the Centre for Popular Memory Archive. The CPM entered legal copyright agreements with interviewees regarding the use of their recordings. This presentation has been supported by grants from the Mellon Foundation and the Centre for Popular Memory.

References

Adeya, C., D. Cogburn (2002). Prospects for the Digital Economy in South Africa: technology, policy, people and strategies. Last consulted 21 January 2004. http://www.intech.unu.edu/publications/discussion-papers/2002-2.htm

Conway, P. Digital Technology made simpler. Northeast Document Conservation Center Section 5. Leaflet 4. Last updated 20 June 2002. Last consulted 19 December 2003. http://www.nedcc.org/plam3/tleaf54.htm

Davies, R. (2004). Globalisation: the challenges facing South Africa. Last modified 27 June. 2003. Last consulted 15 January 2004. http://www.anc.org.za/ancdocs/pubs/umrabulo/articles/globalisation.html

Derrida, J. (1995). Archive Fever. University of Chicago press. Chicago

Harris, V. (2000). Nascence, renaissance and the archive in South Africa, SASA Newsletter, October 2000.

Henriot, P. (1998). Globalisation: Implications for Africa. Last consulted 20 January 2004. http://www.sedos.org/english/global.html

Ngubane, B. (2002). The future is navigable: South African lessons for a digital world. Last modified 21 Jan 2004. Last consulted 21 January 2004. http://www.opendemocracy.net/debates/article-8-85-739.jsp

Statistics South Africa. Last consulted 13 January 2004. http://www.statssa.gov.za