|

158 Lee Avenue ph: +1 416-691-2516 info @ archimuse.com Join

our Mailing

List.

published: March 2004 |

If We Build It, Will They Come? A Year of Testing Distance Learning Using the Web

Christine Sonnabend Vitto, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, USA

Abstract

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum technology staff built a Web interface for distance learning programs using Macromedia Flash. Using this technology, staff in the Museum could connect with groups such as teachers and students in a classroom and bring programs outside the Museum's walls. This technology is capable of synchronous (live) and asynchronous video and audio; for the asynchronous element, there is a component built in that allows PowerPoint presentations, film clips, Web sites, and photos to be shown to the group which the Museum staff member is addressing.

As a member of the Education division staff at the Museum, I was asked to manage and coordinate the testing of this technology with teachers and students, and other groups as appropriate. This paper describes our process of testing and some of the programs that we held - those that worked and those that did not. It also discusses some of the challenges we faced, such as getting staff to buy-in on the technology and the quality of the programs, and what changes we would like to make for the coming year. We are still testing this technology and will be doing more programming over the coming year. We hope to add to our menu of technology options this year, and to improve the Web interface that we designed.

Keywords: distance learning, e-learning, distance education, education, museum education, synchronous learning, asynchronous learning

Introduction

My job in the Education division has been to manage technology projects, including Web sites, and to be the liaison between the Education division and the Technology division. Our decision to venture into distance education was prompted by the requests and questions that we were getting from our audience, although I think that we would have tried it anyway at some point.

For several years Museum staff had been receiving emails that would say something like, "Are you offering videoconferencing tours of the Museum? I can't find any information about it. We would like to sign up." Up until a year and a half ago, our standard response was, "No, we are not doing anything like this at this time." And that would be the end of the contact with that particular person. I like to think of our technology staff as pretty much cutting edge, and that is when both they and I started to realize that in this particular area, we were not ahead of the rest; we would have to run to catch up. Since many other Museums, organizations, and schools were using the electronic medium for education; we decided to try it too.

About a year and a half ago, the Museum started to experiment with distance education technology and programs. Several of us had been very interested in this field and started to do some research on the subject. The technology staff decided to try something different. They built a distance education interface using the Internet and Macromedia Flash to connect to people outside of the Museum's walls. The Director of the technology group approached me and asked if the Education division would be interested in testing this technology with programs aimed at school groups, teachers, and AHO's (Association of Holocaust Organizations). I said yes - and that began our program of distance education.

Figure 1: The Distance Education

connection from "A Teacher's Guide to Distance Learning"

Florida Center for Instruction Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida,

Dr. Ann E. Barron, Executive Director

http://fcit.coedu.usf.edu/DISTANCE/

Goals and Research

Before I could even make some basic decisions about distance education, I needed to see how it worked. The Museum's first program using the new technology was a lecture by Dr. Christopher Browning, author of the book Ordinary Men, to a university class at George Mason University. Dr. Browning was seated in one of our offices, behind the desk, and we used a camera and a laptop computer. The technology worked beautifully, and the students, thrilled to be talking to a famous author in the field of Holocaust research, asked many questions.

The first thing I needed to do for this project, as for any project I manage, was to define the project itself and what needed to be done.

Here is a definition of distance education that I particularly like:

Distance Education is instructional delivery that does not constrain the student to be physically present in the same location as the instructor. Historically, Distance Education meant correspondence study. Today, audio, video, and computer technologies are more common delivery modes. The term Distance Learning is often interchanged with Distance Education. However, this is inaccurate since institutions/instructors control educational delivery while the student is responsible for learning. In other words, Distance Learning is the result of Distance Education. (Steiner, 1995)

Now that I had figured out what it was that I going to do, I needed to set some goals, and define some procedures.

I started out with very simple goals:

- to figure out what distance education was

- to decide if the current proposed technology worked

- to research other forms of delivery for distance education

- to convince others in the Museum that it made sense for our Museum to use distance education as an educational tool.

I spent a lot of time doing research about distance education: what it was, and what other organizations were doing. I made an interesting discovery. There are a huge number of resources out there for higher education and distance education. There are Web sites, organizations, listservs, and conferences galore. There is nothing comparable for museums. Or if there is, I cannot find it, even after a year and a half of research. Therefore, much of my research and information comes from the higher education folks, who are doing a great job of it. The downside of using this material is that museums and higher education are not the same. Therefore, whatever I find out through this research has to be adapted for what we are trying to do.

I began to talk to other Museums and organizations to see what they were doing. Additionally, this research was prompted by possible partnership opportunities with two organizations: the Education Enterprise Zone, discussed below, and Ball State University. I spoke to Lee Livney, Manager of Federal Grants and Distance Education at the Bronx Zoo of the Wildlife Conservation Society; Gene Carlucci, Museum Educator at the Intrepid Sea*Air*Space Museum; April Kim Tonin, Coordinator of Distance Learning and the Teacher Information Center at the Museum of Modern Art; Susan Swarthout, Education Manager at the Museum of Television and Radio, LA; Jeff Arnett at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and Dottie Klugel at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center.

I share my questions for the Education Enterprise Zone partners here, as some of these may help those of you doing similar research. After I started asking these questions and having conversations with these people, I noticed that some of my questions overlapped, or ended up not being relevant to the conversation.

Program Questions

- How many programs do you offer (weekly, monthly, yearly)?

- Who is your audience?

- How did you determine what programs to offer?

- Who created the programs?

- How do you judge the success of your programs?

- How does distance learning or distance education fit into your organization's structure and mission?

- How do you staff these programs?

- How do you see distance learning and this partnership with the EEZ developing over the next 5 years? Ten years?

EEZ Questions

- How did your partnership with the EEZ begin— who contacted whom?

- How would you rate the success of your partnership?

- Would you recommend this partnership to other organizations?

- What do you see as the benefits for your institution?

- What do you see as the benefits for the EEZ?

- What are the drawbacks, if any, of this partnership for your institution?

Technology

- What kind(s) of technology are you using for your programs?

- Are you and your clients, those that receive your programs, satisfied with the technology being used?

- 1What are your recommendations for new technology or improving your current system?

- What is your current success rate (technology-related problems stopping programming)?

- How has the EEZ helped you with this technology?

- How did you determine what programs to offer?

- Who created the programs? How much did Ball State help— either with money or people?

- How do you judge the success of your programs?

- How does distance learning or distance education fit into your organization's structure and mission?

- How do you staff these programs?

- Would you recommend this partnership to other organizations?

- What are the drawbacks, if any, of this partnership for your institution?

- Are you and your clients, those that receive your programs, satisfied with the technology being used?

Not only did doing this research help answer questions about these partnerships, but also they gave me more information about the distance education process, and allowed me to make some valuable contacts in the field. I also began to learn more about the field of education, and some basic principles that I wanted to incorporate into my programs.

The figure below shows a model of learner-centered principles and practices that, I believe, apply to museums as well as higher education.

Figure 2: The National Learning

Infrastructure Initiative (2003) from EDUCAUSE:

Mapping the Learning Space: Learner Centered Principles for Higher Education

http://www.educause.edu/nlii/keythemes/lcp/learningmap.asp

Now that I had begun my research and made some contacts, I began to satisfy my first goal: what is distance education? I began to work on the next two goals: does our technology work, and what other delivery methods for distance learning exist? In order to answer these questions, I needed to actually start doing programs.

Distance Education Programs

The first step was to recruit teachers interested in trying our programs and technology. I started by asking that any e-mails about videoconferencing or electronic programs be sent to me. I then started answering those e-mails with the information that we had Internet-based technology for distance education programs, and that we were willing to try to provide programs for people who would help with our testing process.

The response was overwhelming. I had more people interested than I could provide programs for. As I sorted through the responses, there was a natural drop-off of those for whom we could actually attempt programming. Some could not do Internet-based distance education, like the whole state of New Jersey, for example. Sometimes I would make contact with a teacher and we would start the technology testing, but no matter what we tried, still not be able to make a connection.

This figure shows the types of Internet connections that are possible. We always provide the users, a group of either teachers, or secondary school students, a video connection and audio. The schools always have audio capability, but many do not have any sort of Web camera. So, while they can see us, we cannot see them.

Figure 3: Different types of Internet distance education connections from "A Teacher's Guide to Distance Learning" Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida, Dr. Ann E. Barron, Executive Director http://fcit.coedu.usf.edu/DISTANCE/

The first program we did was in December 2002. To say that the work involved making this happen was arduous is an understatement. We were learning every thing and every detail as we did them. We were making up procedures and processes as we needed them. (true of any new project, though.)

The Education division's historian prepared a general Holocaust session for a group of high school students from Ohio. The teacher had told me that they did not have extensive Holocaust knowledge and they wanted to ask a lot of questions. Our historian prepared a simple PowerPoint lecture, and we loaded it into the interface. The technology testing went very well, and we were ready for the program. It ended up being about 45 minutes long, and it worked very well. The students were able to ask lots of questions, and our historian turned out to be very dynamic over the Web - he is an excellent speaker in person, but you cannot assume that this will carry over to the electronic environment. A week after the program, the teacher contacted me and said that he was bringing his class to the Museum; could they meet Dr. Meinecke in person? He agreed, and they met in the Museum and took many photos.

Method

This is how we make the distance education programs work. I work with one person in the technology group, Greg Jacobson, the designer of the Flash interface, for each program. We agreed early on that we must have a successful technical test before the actual event. This has helped enormously, although sometimes we do spend a large amount of time making the connections work. Once we have a teacher willing to try a program, Greg and I go through the technology hoops to make sure that the class can connect. This means sending a document explaining how to access our ports for the pre-test, and once that works, setting up a time to connect face-to-face (or computer-to-computer) to check the connection.

If the technical test is successful, then we set a date for the actual event. Meanwhile, I work with the teacher on the content of the program. I need to know the grade level and the number of students, plus what the focus of the lesson is to be and what the teacher desires as outcomes. For example, a teacher may want a very general Holocaust lecture from an historian, and may want the students to come away from the experience knowing more about Holocaust history in general, including dispelling many myths.

Once I have the information from the teacher, I look among the staff at the Museum and contact them, trying to find the perfect match. The speaker has to be willing to not only speak to the group, but also commit the time to develop interesting Web content for a program. Once I have the speaker lined up and content set, we are ready to hold the program.

But just because the technical test worked once, does not mean that it will work again - so we have to be prepared to work on the technology again for the actual program itself. What kinds of problems did we have over the year? The audio tended to be the most problematic, and this can be due to many different factors, like: 1) user error on either or both ends; 2) bandwidth issues; 3) time of day and Internet traffic; or 4) faulty equipment.

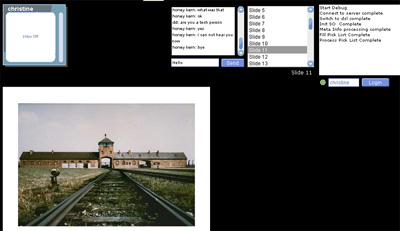

The Interface

Here is a look at what our Distance Education interface looks like:

Figure 4: U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum FlashComm Server Distance Education interface

We ask that the class connect using one computer and use a projection screen so that the rest of the class can see. This is to reduce the load placed on the bandwidth. The class can have a camera, so that we can have two-way visuals, or just use the audio. We first try to get the class to use a microphone through the computer, but a connection through the telephone is a back-up plan, and in fact we have conducted one two-day program for which we used the telephone for the audio.

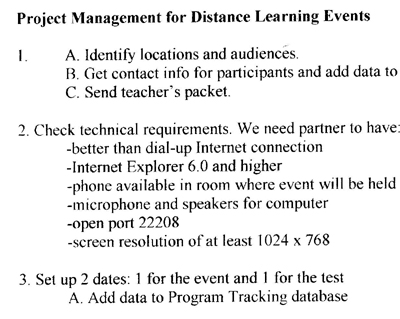

From the trial and error and experience over the last year, I began to develop some documents that have helped me plan and execute distance education programs. First, I developed a list of steps and procedures to follow for each distance education program.

Figure 5: Distance Education Procedures

I ended up developing a distance education checklist - one sheet of paper with a lot of checkboxes that led me through the process - from the original procedures document. I have found that this document is invaluable because of all of the details that need to be taken care of for each program. It also helps with the data entry for reporting purposes.

Figure 6: Distance Education Checklist

Evaluation

I then developed an evaluation that I ask each teacher to fill out after each program. This has proved very useful in helping us make productive changes in our programs and technology.

Figure 7a: Distance Education Evaluation

Figure 7b: Distance Education Evaluation

Even though we were not presenting programs designed for the electronic format, the responses to what we were doing were and are extremely positive. Here is a model of how assessment and evaluation can be done. I believe that evaluation should be a part of every program and that we should always be looking for ways to improve.

Figure 8: Model of On-going Evaluation from "A

Teacher's Guide to Distance Learning" Florida Center for

Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South

Florida, Tampa, Florida, Dr. Ann E. Barron, Executive Director

http://fcit.coedu.usf.edu/DISTANCE/

Right now we are in the process of placing our evaluation questions on a Web site, which will then download the responses into a database. Currently, we use an internal database called the Events Calendar to track the details of the programs and the technical tests.

What Didn't Work

One of our programs that did not work was with a middle school class in the Ft. Worth area of Texas. We held two separate technical tests, and neither one was as good as we hoped. The problem was in the audio - either there was some sort of interference, or the delay and echo was interfering with the delivery of the program. We decided to attempt to hold the program, although we told the teacher that it could be stopped if the problems were too big. Unfortunately for us, we had the Head of the Museum's Council and the Museum's Director interested because the Council Head was from Texas. They planned to be sitting in the Director's Office watching on her computer. The day of the program came, and we tried to get it going. Everyone was watching, but after about 20 minutes, we knew that we could not deliver a quality program, so we stopped. At the time, we believed that the school's connection - 389k - was not good enough. Now, we think the problem might have been somewhere in our system, with the ports. We have since fixed this problem.

Does the Technology Work?

At this point I can answer the next question in the goals: does this technology work? Yes, it works. Does it work all of the time? No, it does not. But when it fails, we research why and try to make improvements. One significant improvement for this year is the fact that the FlashComm interface was moved to a brand new server. This means that we are not competing with other resources on the server. Plus, the server is newer and better. Also, our Technical Services division has started to get involved in the technology for the programs. They are interested in how the programs happen and what their staff can do to make them more successful, from a technology viewpoint.

Other Forms of Delivery for Distance Education

The next question in my goals is: what other forms of delivery exist for distance education programs? To begin to answer this, I began working with the Education Enterprise Zone.

Education Enterprise Zone (EEZ)

About the same time we began testing the technology, I received a phone call from Dr. Stan Silverman from the Education Enterprise Zone (EEZ) based out of the New York Institute of Technology. Their member institutions use videoconferencing technology to do their distance education programs.

Dr. Silverman had called the Museum several years ago to ask about doing some distance learning with us, but we were not ready. This time, I thought we were ready. He and I talked quite a bit about his program, and the possibility of the Museum becoming a member of their organization. That began a long process of research and meetings with staff from the Museum to make this happen.

First I prepared a set of question for Dr. Silverman, and then interviewed him for about an hour. If we were to join his partnership, he promised to provide the Museum with some videoconferencing technology for us to use in addition to our Internet-based Flash product. First, I brought the findings back to the Director of Education and the Director of Technology. Then I presented this information to the technology committee of the Museum. They asked for more information, so I went to Dr. Silverman again and asked him for the names of some of their current partners. I interviewed five of them and wrote up the results with the recommendation that we join. Within days the committee agreed and I called New York with the good news.

Our next step is to have EEZ staff meet in February with Museum staff, and to receive the new videoconferencing equipment. Once we have that in place, we can start training the tech staff on how to use the new equipment, and we can then start testing programs with the new technology.

Other Types of Distance Education Technology

Here are some of the other types of distance education technology I uncovered in my research.

- POTS: Plain Old Telephone System. Can be used by itself, or in combination with a Web-based program or other program. We used the telephone for audio for a program in Florida, using the Flash technology for the video connection. It worked very well. It can get expensive though, depending on phone rates.

- Blogging/Message boards: Blogging (Web blog) is a tool used for asynchronous communication. Users can log into their Web site and create journals, or read anyone else's. Teachers can use them to post information for classes. The newest thing is audio blogging— which is really fantastic. Content can be recorded and downloaded. Message boards can be like a live chat if members are posting at the same time, or can be a space to read and receive information.

- Web-based Technology: this is using an Internet connection to transmit programming: one-way or two-way.

- Instant Messenger - A way to speak instantly over the Internet without phone charges. You type your text messages into a screen. I have actually used Yahoo Instant Messenger, coupled with my Web camera at home, to speak to a friend in Sydney, Australia, and it didn't cost us anything extra.

- Macromedia Flash: Right now we are piloting the Flash technology for the Web. Depends on bandwidth— low to good quality. Equipment needed: Computer, Internet connection faster than dial-up, speakers, microphone, video camera. Software needed: Flash 6.0 and Internet 6.0

- Internet 2 - a non-profit consortium of universities, government and corporations, dedicated to improving technology and access to it. It won't replace the Internet, but rather bring more development of new applications and technologies to users of the Internet http://www.internet2.edu/about/aboutinternet2.html

- Videoconferencing technology: can be ISDN, Web-based (IP), or software. The ISDN and some IP versions use equipment to transmit data.

- ISDN— stands for Integrated Services Digital Network, is a system of digital phone connections that has been available for over a decade. This system allows data to be transmitted simultaneously across the world using end-to-end digital connectivity. Equipment needed: microphone, camera, codec (Coder/Decoder— the device encodes, for transmission, and decodes, upon receipt, digital video and analog audio signals so those signals occupy less bandwidth during transmission), monitor, speaker

- Satellite Technology: not reliant on computers: both sides need sending and receiving equipment: need an uplink to send the images and a downlink to receive them. More mobile - good to high quality Equipment needed: access to satellite dish and uplink and downlink Television: - uses a studio, less mobile, but expensive and high quality Equipment needed: television studio equipment

Challenges

The last of my first year goals is to convince others in the Museum that distance education makes sense. In many ways, this is the hardest thing to do. Fulfilling this goal relates directly to the challenges we have faced over the past year and a half.

The most obvious challenge to a program like this is lack of resources. Unfortunately, we have always had this problem with any project we take on. Believe it or not, the demand for our information, staff time and resources is incredible, even though we have been around for ten years now. The distance education programs are competing with all of the other programs, such as teacher workshops and conferences, presentations by staff, and educational programs held at the Museum. Also, the technology staff and I have taken on this program without giving up any of our regular duties.

While we started pursuing distance education programs, the Museum began its tenth anniversary year. This began a whole series of programs, activities, and events added on top of our regularly scheduled tasks. Therefore, distance education programs are put last on the list of priorities.

Getting staff to buy-in to the concept of distance education is a very tricky problem to solve. Some wholly embrace the idea: I do not have to do more than ask, and they participate. Others are very wary of the idea and are not even sure what it means. I have had to hold meetings, write papers, and otherwise try to educate the Education staff in what distance education is and how it can benefit our Museum. Time is on my side, because as more people learn about distance education, and/or see it in action, they either become excited about the idea, or it becomes more of an accepted part of doing our work.

I do know that the senior management of the Museum is very excited about these new programs, and the new technology. They are beginning to put more support and resources our way as we develop new programs. It is my job now to present information in committees and work with others in the Museum who are doing similar work.

I do not see that this last goal is going to be met, but rather turn into an on-going process.

What Have We Learned?

We have learned a lot over the last year. In fact, I have four new programs so far, as of writing this paper, which will take place this spring.

Working with the teachers and scheduling the programs has become easier in some ways. For example, I do not have to figure out what the next step is in the process. That has already been figured out. What is now harder is to try not to keep creating new things over and over, and to figure out if we can build some programs that can be model programs for new classes.

The technology has become more familiar to me, and technical testing that used to take an hour now takes only ten minutes on average. Also, we understand that we need to maintain flexibility in the programming and technology options, and remain prepared for any situations that can occur.

As well, I know that we need to work harder to create programs specifically for the electronic environment. We are ready to move to the next step with these programs, and I believe that in this next year we will get there.

I believe that our success has shown us that the need for electronic programs is great, and that this Museum can play a leadership and educational role. I have also learned that it is important to consider the Museum's strategic plan and mission, and to make sure that distance education and the methods of delivery fit into these.

New Goals for the New Year

After working on the process and procedures over the past years, I decided that this year, I needed to refine what we were doing. Here are my goals for this year:

- Create educational goals for the division's distance education program, soliciting input from staff in Education and other relevant areas. Incorporate research on states coverage.

- Manage the design process for core programs for middle and high school classrooms, based on sound pedagogical and distance education principles.

- Test programs and evaluate them; make improvements based on feedback.

- Track data related to the distance education program pilot and other distance education programs.

- Incorporate staff and programs from other divisions in designing and assessing programs.

- Conduct research on distance education and possible partnerships for the Museum to pursue. Share results with supervisor and other staff.

The fourth program will be based on a collection of slides taken by a Nazi accountant in the Lodz ghetto. This is a unique collection of about 400 slides, in color. I will be working with staff in the Photo Archives, Collections division, as well as the Education division's museum educators and historian.

Conclusion

We began using the Internet as a way to connect to our audience because we are familiar with that format. During our research we realized that there are many different ways to connect to people, and that sometimes the Internet will not work. We need to be flexible and open to using combinations of technologies and learn about new technology so that we can continue to further our mission to educate the public about the Holocaust.

Upon reflection, I do think that our FlashComm Server technology is successful, and will remain one of the tools that we use for distance education. Our first year of testing was extremely helpful in identifying what we need to do, even when a program did not succeed. I am anticipating having a menu of technology options for programming, as well as a menu of core programs that we will use to educate the public about the Holocaust.

As we continue testing and developing our programs, I am confident that we will develop better and better educational programming, and learn more about the field of distance education so that we can become a leader in that field.

References

Barron, Dr. Ann (1999). A Teacher's Guide to Distance Learning, last updated February 1999, consulted January 16, 2004 http://fcit.coedu.usf.edu/DISTANCE/

Distance Learning Resource Network (2000), Challenges and Solutions for Online Instructors, consulted January 2, 2004. http://www.dlrn.org/library/dl/challenges.html

EDUCAUSE, National Learning Infrastructure Initiative (2003), Mapping the Learning Space: Learner Centered Principles for Higher Education, last updated 11-21-2003 9:15:27 a.m. consulted January 2, 2004. http://www.educause.edu/nlii/keythemes/lcp/

Prensky, M. (2003). "e-Nough!". On the Horizon, Volume 11, Number 1, March 2003.

Steiner, Virginia (1995), What is Distance Education?. In Distance Learning Resource Network Library, 1995.