Betsy James DiSalvo, University of Pittsburgh; and Abigail Franzen-Sheehan, The Andy Warhol Museum, USA

http://edu.warhol.org/index2.html

Abstract

The Andy Warhol Museum (TAWM) is one of the largest single artist museums in the world. TAWM's mission is to use the art, life and practice of Andy Warhol as a catalyst for public dialogue and learning. Using a single artist approach can present a challenge that many institutions with seemingly finite scopes, like TAWM, must address: educators do not readily see the broader applications and opportunities for learning available within these museum contexts. To help teachers make connections between Warhol's life, work, commentary on popular culture and diverse academic subjects, TAWM Education Department has developed a new on-line resource for teachers: The Warhol: Resources and Lessons. This new on-line effort emphasizes teaching across the humanities, crossing disciplines, and encourages teachers to collaborate and create learning experiences that help students understand the intertwining relationships between history, pop culture, literature, music, visual arts, and the media.

This paper will review stages of its development, user testing, evaluation findings, and the implementation of these findings. We review teachers' feedback on content needs for curriculum as well as the context-setting needed to house educational resources in an on-line environment. The importance of user testing and working with the intended audience throughout all stages of development is emphasized. Within these findings we present suggested heuristics for inter-disciplinary and visual arts curriculum Web site development that can be used at other museums.

Keywords: curriculum, evaluation, cross-disciplinary, visual arts, education, humanities, artist, Warhol

Introduction

The Andy Warhol Museum (TAWM) is one of the largest single artist museums in the world and has been exploring popular culture through the lens of Warhol's work, life and practice for more than a decade. Andy Warhol embraced infinite creative processes, and his influence has made him one of the most important artists of our time. Throughout the public programs, exhibitions, and educational offerings, the museum's unique philosophy of using a single artist's practice as a framework for learning has been very successful, but it can also present a challenge. Like other institutions of concentrated scope, the single artist focus of the Warhol can be perceived by the public as finite. Educators do not readily see the broader applications and opportunities for learning available within these museum contexts. A common expectation is that the educational content of the Warhol is appropriate for only high school or college visual arts teachers with a specific mandate to teach Pop Art. But in fact, Warhol's rich life and work, as well as his strong commentary on popular culture, make him an excellent topic for use in a wide variety of academic subjects. To help teachers make these connections, TAWM Education Department has developed a content rich Web site, The Warhol: Resources and Lessons, teaching across the humanities, that encourages teachers to explore, experiment, and collaborate across disciplines, creating learning experiences that help students understand the relationships between history, literature, pop culture, music, visual arts and the media.

The Warhol site content draws from ten years of development work in educationally driven exhibitions; artist residencies; school outreaches; teacher workshops; public programs; interpretive labeling; and such printed teacher resources as Education News. The Web site was born out of demand by audiences for more resources. The museum wrote numerous grants applications to establish funding for an on-line resource, receiving seed money, as well as a larger grant from Alcoa Foundation.

During the first stages of development, the Warhol had to refocus the site to settle the push and pull between the aesthetic needs of the site to represent a contemporary art museum and the utilitarian and text-based needs of teacher users. They engaged University of Pittsburgh Center for Learning in Out of School Environments (UPCLOSE) to evaluate the site while it was in development. In a three-phase evaluation process, UPCLOSE presented feedback from the target audience and education stakeholders to shape the development of the site.

This paper will review the three stages of user testing and implementation of the findings into the final Warhol: Resources and Lessons Web site. We draw from the experiences of working with teachers as authors and collaborators to suggest heuristics for inter-disciplinary and visual arts curriculum Web site development that can be used at other museums.

Background

TAWM worked from 2002 onward to expand the educational offerings, and the museum's growth including on-line educational resources. The initial stages were funded by smaller "seed" grants from W.L. Spencer Foundation and Verizon. In 2005, in conjunction with a traveling exhibition to Russia, Andy Warhol: Artist of Modern Life, TAWM secured funding from the Alcoa Foundation to produce the interdisciplinary on-line curriculum in English and Russian. The Alcoa Corporation had recently acquired aluminum fabricating facilities in Russia, and the cultural and educational benefits of this curriculum corresponded with their desire to bring technology and interdisciplinary education to communities in Russian as well as in English speaking countries. The Web site's educational goals were to expand the educational services and role of TAWM locally, nationally, and internationally by developing unique interdisciplinary on-line curriculum that models teaching and learning in and through the arts using a single artist's work and practice. Ongoing objectives of the Web site include:

- Motivating students through the use of art in diverse disciplines

- Fostering critical and creative thinking

- Engaging users with curriculum content, the museum and contemporary artists

- Showcasing unique projects with local schools and artists on an international platform

- Disseminating high-quality curriculum materials that strengthen art and interdisciplinary teaching and learning in schools

Rationale and Research

From an art education perspective, it is not enough to teach technique alone. Engaging students in life's essential questions, and finding ways to explore big ideas that interweave a development of content and form, are the responsibility of educators (Gogan, 2006). TAWM created a curriculum model based on artistic practice to help teachers meet these goals. Responsive to the new Pennsylvania curriculum standards, the site helps teachers connect and apply the site content to existing class curricula beyond the art room. The connection between the artistic practice and inter-disciplinary nature of Warhol's work, as well as that of other artists featured on the site, offers context and experience with topics across the Humanities disciplines. Andy Warhol is usually thought of as a painter, but his careers also included photographer, writer, music promoter, filmmaker, collector and even fashion model. This diversity offers rich examples of an artist who embraced interdisciplinary thinking. His extensive art practices provide a template for interdisciplinary education, exploring historical and cultural contexts, cultural awareness, civic engagement, literacy, the creative process, critical thinking, and skills and career development.

Research supports using artistic practice as an interdisciplinary and cross-curricular learning model. In the series Art Education in Practice, Sydney R. Walker explores methodologies for teaching meaning in art making. He outlines characteristics of artists' practices, citing the following as crucial: purposeful play, risk-taking, experimentation, postponement of final meaning, searching, and questioning (Walker, 2001). It is this sense of engaging students in what art "does," focusing on "the work" rather than "a work" of art that is core to effective art education (Dewey, 1934). Also, using artistic practice as a framework necessitates interaction between personal, socio-cultural, and physical contexts. This reflects the model of effective learning as described by learning researchers John Falk and Lynn Dierking (2000).

The interdisciplinary offerings of the site also support ongoing efforts to develop new audiences for the museum. In a critical evaluation of art museums, Eisner and Dobbs (1986) asserted, "museum educators seem to lack a well-defined vision of their responsibilities and the methodologies necessary to develop new audiences for the Museum." A follow up study indicated that the majority of museum professionals viewed the development of new audiences as the responsibility of the education department (Williams, 1996). If new audience development is expected, then what training, tools, and resources do education departments need to implement?

These studies furthermore assert that lack of training in evaluation and research methodologies makes it difficult for museums to assess the needs of their audiences, both new and existing, as well as the effectiveness of their programs. In the Warhol's site development, the use of design research methodologies became a tool for conducting formative research on the needs, abilities and effectiveness of on-line curriculum for the art teachers and humanities teachers.

Teachers were appreciably interested in other teachers' contributions and feedback about educational resources. This supports research that indicates teachers' visits to museums are strongly influenced by other teachers (Mackety, 2004; Institute of Museum and Library Services, 1998). Throughout the research process, we found teachers' contributions on the site to be a rich source of new content and a method of grassroots promotion.

Content

The curriculum is designed for middle and high school students and aligned with the Pennsylvania Academic Standards for Arts and Humanities. Creative learning assessments are integrated within instructional units and each lesson and activity has been tested both in the museum and by working teachers to ensure its relevancy and effectiveness. The site includes student work examples and teacher adaptations of curriculum. Taking advantage of new technology, the curriculum features student podcasts, audio and video clips, printable versions and downloadable PowerPoint presentations.

The site features the following areas:

- The One-Day Art & Activities section provides one-day activities using a specific work of art as a springboard into a subject, series, or method.

Fig 1: The One Day Art and Activities page of The Warhol Resources and Lessons Web site http://edu.warhol.org/aract.html

- In-Depth Unit Lesson Plans provide longer units of study addressing Creative Thinking and Making, Critical Thinking and Historical and Cultural Context.

Fig 2: The Menu page for Unit Lesson Plans of The Warhol Resources and Lessons Web site http://edu.warhol.org/ulp.html

- Interactive features such as "Time Capsule 21" an on-line replica of one of Andy Warhol's Time Capsules.

Fig 3: The Home page of Time Capsule 21 http://www.warhol.org/tc21/

Phase I

In an effort to create a beautiful aesthetic, the first iteration of the site was given a clean and sparse design to feature the contemporary art of Andy Warhol. The front page was intended to invite user navigation through artworks that represented themes for exploration. This premise had been used successfully in another on-line project, http://www.warhol.org/tc21/ that had won several awards. However, in this iteration, users did not understand what the site offered or for whom it was intended.

Fig 4: The first iteration home page was live in the Russian language version before the English version.

Fig 5: The first iteration home page in the English version had some design modifications.

In October 2005, UPCLOSE reviewed the first iteration of the site. For this preliminary formative evaluation, five practicing teachers were recruited from a non-profit organization promoting art education in the region. These participants had an average of 12 years of teaching in middle and high schools. The survey group consisted of four Visual Art teachers and one English teacher, and all taught in Southwestern Pennsylvania. Data was collected using a semi-structured telephone interview method. Each participant was contacted individually via telephone, and the interviews were audio taped. Researchers took notes on participants' exploration of the Web site and responses to questions posed.

The surveys began with a set of general questions about the participants" professional and computer experience. Then, using a think-aloud protocol, participants were directed to explore the Web site for a short time with occasional prompts from the researcher if needed. This survey focused on a completed section, "One-Day Art & Activities" .

The Warhol initially assumed users could be drawn into the content through artworks and visuals with minimal guides. However, the first on-line versions did not provide adequate navigation to reach the rich content. The clean white space and small text in low-contrast color made it very difficult for users to read. The pages were not legible as a projection in a classroom environment, nor for multiple users at one monitor. The visual design proved unpopular because it was not considered representative of Andy Warhol and might not catch the attention of the students. Usability issues were found with the navigation: users feeling lost, unsure of where they were or where they could go. In addition, some teachers could not access the site because it required a plug-in Flash application not available at their school's workstations.

Despite these difficulties, teachers were impressed and enthusiastic about the rich content resources and curricula available on the site. The content was developed over a decade through prototypes and workshops, where both art and humanities teachers worked closely with museum educators. Teacher input and feedback dramatically shaped these lessons, making them viable for classroom use as well as attractive in their clear explanations of complex ideas. TAWM's practice of curricula development incorporates design research methods and is a critical part of creating value in the site. Each museum has its own useful methods of developing programming, but incorporating the Warhol's example of working extensively with the intended audience, in this case teachers from various disciplines, will serve museums well in developing on-line content that can help museums break out of their traditional audience.

The initial user evaluations provided a general understanding of the technology resources and abilities of teachers in the region. The evaluations examined what visual and textual indicators were needed for teachers to determine in the first moments of visiting if the site would be of value to them, and can be conducted with sample home pages that fit different concepts for site direction.

While teachers understood that the site was "Arty," it was difficult for them to navigate, and they did not think that their students would find it appealing. After reviewing this feedback, the Warhol and the design firm tried to negotiate a best solution, followed by a decision to part ways. This was a challenging result for the museum due to the tight deadline of the Web project expected to concur with traveling exhibition dates. TAWM's previous use of designers for on-line activities served general audiences and not educators specifically. Because of this, the design firm did not anticipate a higher priority on usability over aesthetics. In future development, the museums and designers should explore user research with all of the team members having direct contact with end users.

Phase II

The Warhol was responsive to the user feedback and redesigned the site with bold bright visuals in grid patterns. This second iteration was successful for setting the context of an educational site featuring Warhol's work and Pop art in general. In usability testing, however, there were still teachers who did not understand all of the intended goals of the site as outlined by TAWM.

Fig 6: The Warhol: Resources and Lessons home page during the second phase of user testing. The cross-disciplinary nature of the content was still not readily clear.

Phase II consisted of interviews with fifteen teachers recruited from a non-profit organization promoting art education in the region. These K-12 teachers had an average of 16.5 years experience. The survey group consisted of nine Studio Art and Art History teachers; five Music teachers; one Theatre Arts teacher, and one English teacher, twelve participants were from Southwestern Pennsylvania, and two were from other states. Data was collected using a semi-structured individual telephone interview method and audio taped while the researchers took notes on participants' exploration and responses. Participants were randomly placed into three groups. Each group focused on a specific section of the Web site. The surveys began with a set of general questions about the participants" professional and computer experience. Then, using a think-aloud protocol, participants were directed to explore the Web site for a short time with occasional prompts from the researcher if needed.

All participants enjoyed the look and feel of the Web site and felt the visual style was appropriate for an art education resource. Several commented that the visual style reflected their expectations for a Web site about Warhol or TAWM. Participants understood the context to be a site for educators, primarily applicable for art and design related coursework. Still, the site's stated intent to support teaching across humanities was less clearly understood. Some participants did not initially realize that the content would extend beyond Warhol's work or the museum itself. This confusion limited the anticipated usefulness of the site, especially for those teaching outside the visual arts. It was imperative in the next iteration to be mindful of the initial goal to disseminate high-quality curriculum materials that strengthen art and interdisciplinary teaching during development. While higher-level goals such as this may be refined based on user input, without a guiding framework, positive responses to a site can sidetrack the project team into missing opportunities in future iterations.

At times the intended audience was unclear; for example, one teacher initially thought the site would be for introductory coursework but realized during her exploration that it was intended for advanced students. Additionally, confusion surrounded the relationship between other artists featured on the site and Andy Warhol. It was not until participants delved deeper into the content that the intent of the site and opportunities for interdisciplinary projects became clear. The content was not the obstacle in attracting the correct audience: the problem again lay in the context or housing of these rich resources.

Most user-study participants felt the site would be valuable for gathering curriculum ideas and incorporating new activities into existing lesson plans. However, the navigation confused some teachers. They were frustrated by not immediately finding overviews of each section and concise descriptions of the lesson plans. The findings show that busy teachers with limited computer time need to be able to quickly identify the utility of the site resources. Seemingly small issues, such the availability of PowerPoint presentations, large enough text for projection, and pages formatted for print, were the items that teachers indicated would bring them back to the site repeatedly. Teachers said they might print from their browser or by cutting and pasting because they did not notice the PDF printable content in the menu. And while teachers had access to projectors, their skill in processing images for projection varied. The lack of PowerPoint-ready images or PDFs might deter their inclusion of the information in a class, as would downloading large size files. The ability to find and use tools for the classroom will encourage teachers to use the site regularly instead of as a one-time inspiration.

User testing highlighted another area for internal review: the use of content dealing with violence and death. Two teachers expressed concern regarding the elementary age-appropriateness of these specific art works and activities. TAWM values art in its ability to be a catalyst for discussion, in this case about media literacy and the second amendment. The museum chose to re-title these lessons instead of censoring them. When considering the inclusion of provocative content, museums must weigh the audiences' possible negative perceptions with their institutional goals. A secondary home page could be created when educators have concerns over the appropriateness of content in the larger site, thus limiting the opportunity for younger students to encounter some of the more provocative images that the Warhol site and other museums have. In this way, younger audiences will have access to some content without limiting content for others.

As indicated in research, teachers are influenced by their peers' endorsement of museum resources (Mackaty, 2003; IMLS 1998). Information showing other teachers' use of the site and sample student work was considered extremely valuable by some teachers in this phase. They felt more teacher reviews and examples would validate the site and keep the content fresh, thus encouraging teachers to revisit the site regularly.

Phase III

In the third iteration of the site, simple visual and textual clues were included on the home page to provide better context. The organization of the lesson plans was standardized for navigational ease and a list of links to lesson plans based on discipline areas was added. Even if teachers did not explore these areas immediately, they understood that lessons for disciplines besides visual arts were available, therefore helping set the context for cross-disciplinary teaching.

Fig 7: User feedback shaped the signpost and language that set the context for the third iteration of the site.

The testing in Phase III shifted to an on-line survey methodology. E-mail recruitment yielded 112 invited respondents over two months during the summer of 2006. Content was continually added, and minor modifications were made to the usability of the site during the run of the on-line survey. Teachers were recruited using existing Warhol Educator databases, professional list serves, message boards, and a request on the main Web site of TAWM. Participants were asked to explore The Warhol: Resources & Lessons Web site for 15 minutes and then answer questions using an on-line survey. The survey consisted of three sections, User Information, Content Usefulness, and Usability Assessment.

The participants represent a range of experience teaching between 1-15+ years.

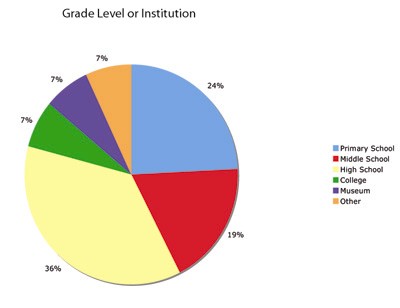

Fig 8: Most participants (86%) were teachers in schools and 14% were museum educations or other types of educators including administrators.

Fig 9: Subject areas and disciplines

Visual Arts teachers were the largest group of participants and most other participants were Humanities teachers. The largest audience was teachers in the Pittsburgh region, represented in the number of respondents from Pennsylvania (41%); however educators from over 27 states and 4 countries (France, Switzerland, England and the Ukraine) also participated. Participants represented urban areas (48%), suburban areas (40%), and rural areas (12%).

General Findings

The findings show that teachers are using museums' on-line resources for full lesson plans, for lesson ideas, for general research and for image resources far more frequently than we anticipated. We provided a list of museums with good curriculum and respondents indicated that they had used the museums listed with frequency:

- National Gallery of Art (52.1%)

- The Smithsonian Institution (52.1%)

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) (46.6%)

- Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) (43.8%)

- Getty Museum (31.5%)

- The Art Institute of Chicago (28.8%)

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) (15.1%)

- Walker Art Center (6.8%)

To further understand teachers' interest in on-line lessons from TAWM, we asked participants, "How often do you visit TAWM with your class?" Of the survey respondents, 17% responded that they visit once a year or more, 58% responded "never", and 25% responded "N/A." And when we asked, "How often do you use the on-line resources available at the Warhol's Web site?" 47% of educators responded that they use the Warhol on-line resources once a year or more. This indicates that because of the large number of respondents from Pennsylvania, the museum is a significant resource for teachers in the region.

To understand more general use of the Internet and on-line resources, we asked, "How often do you use the Internet to research and develop curriculum for your class?"; 61% responded "weekly" and 23% responded "monthly." When asked, "How often do you present visual media in your classroom?," 69% responded "weekly" and 14% responded "monthly." These figures indicate the Warhol has promising opportunities to gain new audiences and provide quality resources on artistic practices on-line.

When asked, "How would you describe the value of this site to another teacher?", 95% of the responses were very positive. Positive responses included general appeal and usability such as the following comment:

Outstanding! The Museum has done an amazing job of connecting art to the standards and interdisciplinary subjects. Students from K-12 to higher education can learn so much!

Many found the depth of the content available to be of value:

I didn't know about the depth of the education portion of the site until now. It's a great site for making connections with contemporary and modern art in the classroom.

And many saw opportunities for interdisciplinary applications, including some very specific prospects:

I would highly recommend it. I teach Sociology and Psychology. Within the first minute I found 4-6 lessons that I could incorporate into my curriculum. This is very valuable because I want to make those classes more visual. It is very difficult to find lessons that are that practical for my class. One I plan to use as soon as school starts back in Sociology is the lesson on Hammer and Sickle: Interpreting meaning in symbols. For Psychology - History and memory - Collective memory. Each lesson has enough info to work on tailoring it to your needs without being overwhelming.

When asked about their anticipated use of the Warhol site, the responses were positive with over 80% responding that they strongly agreed or agreed they would be able to use the content and images from the site in their classroom. For planning activities in the classroom, 86% strongly agreed or agreed that the site would be useful, and 78% strongly agreed or agreed the site would help them when developing curriculum to meet required standards. Almost all (95%) indicated that they would recommend the site to a colleague, and 82% of the respondents indicated that they would bookmark the site.

Interdisciplinary Opportunities

The large number of educators working in collaboration was surprising. To assess current collaboration, the survey asked, "How often do you collaborate with other teachers?"; 65% of the respondents indicated that they collaborate monthly (26%) or weekly (39%). The use of collaborative methods promoted by the site offers visual arts teachers a chance to continue to expose students to the visual arts (while federal funding is being cut to visual arts) and for Humanities teachers to use artistic practice and experiences as a way to create more meaningful lessons. TAWM had concerns that the focus on specific artists would not be applicable to K-12 teachers because they taught art practices and did not readily use the work of current and historic figures in their teaching. But when asked, "How often do you focus on a specific artist and his/her practice in your classroom?", over half (56%) of the educators responded that they do monthly or weekly.

With few sites focusing on teaching across the humanities, museums have an opportunity to increase their impact inside on schools by offering curriculum and resources for teachers on-line. Moreover, museums, particularly art museums, have an opportunity to move beyond their practice area by offering teachers in other disciplines new tools and perspectives on teaching across the Humanities. For example, TAWM is seen by many as a resource for art education, but the work of the museum has far broader application and with the right tools can provide dynamic ways of using the arts to advance other core curriculum goals. Museums can use this opportunity to meet the needs of schools striving to present cross-curricular lessons as a strategy to deal with crowded curricula.

When we asked a series of questions about The Warhol: Resources & Lessons Web site and its success for teaching across the humanities, most teachers agreed that is was a valuable resource for interdisciplinary work.

Fig 10: Teaching Across the Humanities Stats

Answering Usability Issues

Teachers found the current iteration of the site to have good usability and navigation. While the site's navigation is much improved from previous evaluations of the site, suggested future improvements include a more systematic approach to navigation and a standardized frame for the lessons.

The final segment of the survey asked general usability questions. The responses were positive, with 80% or more educators responding that they strongly agree or agree to all of following statements about usability:

- It was easy to use the site.

- The information was clearly presented.

- The navigation was easy to use.

- I liked the overall look and feel of the site.

- I could find what I was looking for.

In order to learn more specifically about the usability of the site, the survey asked, "How could we improve this site for you?" Of the 45 responses, most were extremely positive with no direct suggestions: "I will let you know after I implement a few of the lessons next year! Thanks tons for developing this site!"

The most common suggestions were for additional content to assist with cross-disciplinary curriculum to meet their particular interest area, more video, sound clips and interactive experiences, and more content specific to elementary students. Teachers also asked for space to include their comments and ways to update the site, and suggested continual addition of content so that it remains new and interesting: "Provide opportunities for user-generated content that shows how teachers use the site to generate new lessons and student work."

To gain specific feedback on what was positive and negative about the site, we asked teachers two open-ended questions. Sixty-three teachers provided specific feedback when asked, "What are the most positive aspects of the site?" Many wrote about the general usefulness or specific content: "The PowerPoint presentations, the unique lesson ideas. The fact that other artists can be explored in addition to Warhol."

The quality of content elicited the most responses: "There is still a depth of content while still being attractive and nice to use. There's honestly more content than I would ever likely read all through, but that's a good thing. It means I will keep coming back."

Finally, a major theme in the comments was the interdisciplinary nature of the resources:

There are images, related stories and links, student examples, information about the work of a museum, collecting, etc. that a lot of people and students don't know about but may be interested in - puts things in a different perspective. The biggest thing - you don't have to teach art to use the site in class or feel like a loser because you don't (teach art).

When asked, "What are the most negative aspects of the site?", 39 offered specific feedback but little consistency in that feedback. Seven had issues with the usability or navigation, and five had problems with computer compatibility or low bandwidth. Most responses requested additional content, and three comments suggested the amount of content could be overwhelming.

In future development, a systematic approach to building the site architecture will assist in developing new content and limit the number of errors. Errors on a site not only cause teachers to look for more technologically reliable resources, but also suggest that the intellectual content is not reliable. Links to report technical errors would be helpful in any new development, as would employing a teacher (or intended end user) with limited computer experience to conduct a systematic usability test of the site.

Discussion

The Warhol's experience in developing Warhol: Resources and Lessons can show us some general themes for future development of such on-line cross-disciplinary curricula. Many of these themes focus on working with teachers as audience, authors and ambassadors. The inclusion of teachers' feedback in the curriculum content, the on-line navigation, and the design and communication of the cross-disciplinary intent created a successful marriage of content and form.

The value of formative research in developing the content and the on-line delivery is immeasurable. Ongoing rigorous development through school workshops, outreach programs and collaborations with teachers is an important reason the content is regarded as "rich" and "thoughtful". Museum education departments have many different and effective methods of developing curriculum, and the inclusion of a collaborative process with teachers will not only improve the quality of the content; it will also increase teachers' ownership, and endorsement will bring peer recognition.

TAWM's first and less successful iteration, an on-line gallery, also points to the need to include the target audience in the contextual stages even after much of the text has been created. Museum educators may not be able to engage outside evaluation in every case of delivering curriculum on-line, but they can conduct some basic user research. There are options that can give insights on users with out extensive training; such as "low-fi" prototyping (Retting, 1994) and observations of teachers (Hackos & Redish, 1998). Team members can also adapt personas of "typical users" and act out experiences using the site to meet projected goals. These basic heuristic evaluations provide quick and inexpensive methods to uncover usability issues before final production (Nielson, 1994). During site development, Cognitive Walkthroughs (leading users through an experience) allow for a general assessment of general functionality and can help the museum understand teachers' goals in using on-line resources (Lewis and Wharton, 1997).

An outside expert is able to provide fresh perspectives, but considering museum budgets and timelines, an informed outsider viewpoint can also be gleaned from a docent group or student teacher intern. The site designers should be invited and encouraged to talk with teachers, observe, and participate in iterative testing to gain teacher buy-in so that the evaluative process is legitimate and provides more objective insights.

The context of the site, in the first iteration, was a roadblock to teachers trying to reach the rich content. In the second iteration of the site, the museum took some basic feedback from the Phase I evaluation and developed a site that had most of the components necessary to deliver their valuable content. The third iteration of the site was refined to meet their higher goals. This iterative process with continual reflection on the initial objectives was imperative to create the proper context or housing for the site so that the rich interdisciplinary content would be valued and used, and the higher-level goals could be met.

Raising awareness in the target audience about the availability of lessons and resources on the Warhol site will be an ongoing challenge. While the response to the site was overwhelmingly positive, the need to market this valuable resource is strong. Many of the teachers indicated that they will be recommending the site to others, and this sort of grass-roots marketing will be essential in building a user base for the site. Within their interviews there were some specific comments about how to raise awareness of the site and what functionalities they would need in the site to encourage peers to visit.

Some of the recommendations were simple marketing tools, such as providing an icon link for their school's Web site or e-mail links to suggest the site to others. Other recommendations were more viral in nature; as teachers developed the curricula with the Warhol, their personal investment grew, and they contributed their comments and school projects to the site. By utilizing the teachers' enthusiasm to become authors of the site, the museum can raise awareness from the teacher/authors' self-promotion with their peers. By sending links to their own projects and content, teachers imply endorsement of the whole site and the idea of cross-disciplinary links to the museum. This collegial network, this sharing of resources, is a strong influence on teachers' use of museums and content sources.

In the final evaluation, teachers indicated they enjoyed and respected how the content was organized and communicated. They wanted more topics and tools provided in the same way. Some wanted underrepresented groups to be more heavily featured; others wanted new media and tools, or more content for additional disciplines. Offering opportunities for teachers to provide ongoing feedback will not only raise awareness but also could help the museum prioritize the development of new content. This should be balanced with content, directed at new audiences, developed around curriculum standards that have yet to be addressed.

Acknowledgements

The Warhol: Resources & Lessons is developed and produced by the Education Department at TAWM and a collaborative team of Museum staff, teachers, artists, researchers and youth. See site credits for complete list: http://edu.warhol.org/smapcred.html

References

Csikszentmihalyi, M. & K. Hermanson(1995)."Intrinsic motivation in museums: What makes visitors want to learn?"Museum News. May/June. 35.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. New York: Perigee Books, 162.

Eisner, E., & S. Dobbs (1986). The uncertain profession: Observations on the state of museum education in twenty American art museums. Santa Monica, CA: The J. Paul Getty Trust

Falk, J. H., & L.D. Dierking (2000). Learning from museums: Visitors experiences and the making of meaning. Lanham, MD: AltaMira.

Gogan, J. (2006). Artistic practice as a framework for learning. The Andy Warhol Museum [unpublished paper.]

Hackos, J.T. & J.C. Redish (1998). User and task analysis for interface design. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Institute of Museum and Library Services (1998). True needs, true partners: 1998 survey highlight. Museums serving schools. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Museum and Library Services.

James, W. (1890). The Principles of Psychology. New York: Holt.

Lewis, C. & C. Wharton (1997). "Cognitive walkthroughs". In M. Helander, TK Landaur, P. Prabhu (eds.) Handbook of human-computer interaction. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V. 717-732.

Mackety, D.M. (2003). Museums and schools: "Identifying teachers' museum needs:. In American Association of Museums:Current Trends in Audience Research and Evaluation 16. 33-40.

Nielsen, J. (1994). Heuristic evaluation.In J. Nielsen & R. L. Mack (eds.) Usability inspection methods. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 25-62.

Rettig, M. (1994). Prototyping for tiny fingers.Communications of the ACM, Vol. 37, No. 4. 21-27.

Walker, S. (2001). "Teaching Meaning in Artmaking". Art Education in Practice Series. Worcester: Davis Publications, 115-154.

Williams, B.L. (1996). "An examination of art museum education practices since 1984". Studies in Art Education, Vol. 38, No 1. 33-49.

Cite as:

DiSalvo, B.J. and A. Franzen-Sheehan, Expanding Art Museums into Humanities Classrooms: Research on On-line Curricula for Cross-Disciplinary Study, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2007 Consulted http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/diSalvo/diSalvo.html

Editorial Note