Andrew Fox, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, USA

Abstract

When planning interactive and electronic signage installations in the new de Young museum, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco looked to existing Web-based resources to help manage these programs. Our approach was shaped by both philosophical and practical concerns, and emphasized the repurposing of existing Web content and content types, as well as a familiar back-end interface already in use by numerous FAMSF staff members for maximum usability and efficiency.

Keywords: content management, applications of the Web by museums, new tools and processes, electronic signage, educational interactives

Introduction

Over the past ten years, museums have invested in the development of a range of digital information resources, from Web sites and collections databases to educational interactives, electronic signage and digital audio guides. Even a casual review of Museums and the Web proceedings shows that new information resources have fundamentally altered the ways museums communicate with their audiences. In most cases, the creation and maintenance of new digital assets has also required a major commitment of staff time and direct financial investment.

Historically, digital information resources have often been developed by museums as stand-alone efforts. The in-gallery educational interactive, the Web site, and the signage system are often created and managed by different departments. They may be on different, even proprietary, systems. The information they present is rarely managed from a central point or shared dynamically across different platforms and applications.

With the opening of the landmark new de Young museum, designed by renowned architects Herzog & de Meuron, in October, 2005, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF) sought to take a more integrated approach to the challenge of developing and presenting the digital information resources planned for the building. The most obvious direction involved utilizing FAMSF’s largest and best-known digital asset, its Web site and landmark on-line collection database or ‘ImageBase’, http://www.thinker.org/. One of the first of its kind in the museum world, FAMSF on-line collections database was launched in 1996, and won ‘Best Research Site’ at Museums and the Web 1997. The Web site has since been improved and expanded upon over the last nine years.

Fig 1: The home page of the FAMSF Web site http://www.thinker.org

With its existing infrastructure and systems, the Web site was a logical point of departure for the digital resources planned for the new de Young. These included, and in the end were limited to, three arrays of regularly updated electronic signs, and interactive kiosks allowing visitors to explore the holdings of the de Young’s textile collections in-depth. The data-driven nature of the Web site meant that the nearly all of the museum’s collections, programs, and exhibitions were listed on-line, and much of this information would necessarily be redeployed in both electronic signage and interactive kiosks.

Furthermore, the Web site was powered by a browser-based content management system (CMS) - Mediatrope’s Sitebots - that allowed for updating of information by non-technical museum staff, and enabled a single Web master to maintain a large, diverse Web site in-house.

Fig 2: The Sitebots CMS

In concept, it seemed both redundant and impractical to have museum staff enter two identical sets of information for two different purposes, and the idea was born to harness the power of the CMS to provide data for the de Young’s installations. Lastly, there were, as with all museum projects, economic concerns. It seemed far more viable to use our existing CMS system than pay for the research and development of something new. Again, since many of the data types were the same, it seemed the natural course to take.

Fig 3: We elected to leverage Web-based data sources and our Content Management System for the signage and Textile interactives at the new de Young. Data is entered once and published to multiple platforms. The system is managed through a single CMS.

Textile Study Center Interactives

Origins and Goals

The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (the de Young and its sister museum, the Legion of Honor) boast a major textiles collection of more than 20,000 objects. However, the textile collections remain one of the undiscovered jewels of the institution because of limited exhibition space and the fragile nature of the objects. Limited gallery space means that only a tiny percentage of the collection is ever on view. While this is an issue for the entire museum, (and indeed for most museums), public access is a particular challenge with this collection: the textile galleries rotate more frequently than others because of the unique conservation requirements of the objects.

The new de Young museum features several new public spaces dedicated to the textile collections. In addition to expanded galleries, the museum includes both research library as well as a textile study center with visible storage drawers. The textile study center is also home to a new educational interactive available on two Apple iMac work stations. Expanding public access to the textile collections was the primary goal of the new interactives. The interactives were also designed to provide an introduction to textiles as art objects and artifacts through various perspectives on the Museums’ collections.

Building On Existing Web-Based Resources

In our initial planning for the Textile interactives, we used the Museums’ existing Web resources as building blocks. FAMSF’s on-line collections database represented one of the Museums’ largest public education resources and, at the time, a nine-year investment in collections data and images. The on-line collections provided a strong foundation for the interactives. In addition, there had long been a desire to find ways of making the on-line collections accessible from within the museum, and the interactives offered a clear path to achieving this goal.

However, we didn’t want to simply reproduce the on-line collections on a workstation. The on-line collections contain images and information about more than 82,000 objects - 75% of the Museums’ entire collection - offering a wide view of FAMSF’s collections. But the on-line collections, despite their scope, lacked depth and context. On-line visitors could browse dozens of Anatolian kilim rugs, zooming in to view the objects in extraordinary detail, but the on-line collections provided no information on, for example, the definition of “kilim” or the location of Anatolia.

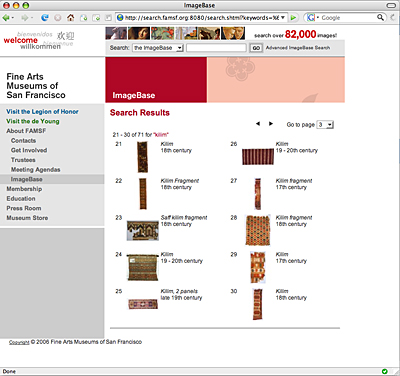

Fig 4: The FAMSF online collections http://www.famsf.org

Our approach to the interactives was also shaped by lessons learned in the creation and management of our Web site. The interactives were designed to be easy to modify and expand, and to be managed by non-technical staff. In this case, content development and ongoing maintenance would be done by textile curators, using the same CMS that other staff use to manage FAMSF’s Web site.

Design and Content

The interactives provide visitors with many ways to explore and learn about a particular object or browse more than 12,000 textile collections objects. The CMS provides the same collections objects as building blocks for textile curators to create new content and ‘chapters’ of the interactive with text, images, audio, video and Flash animations.

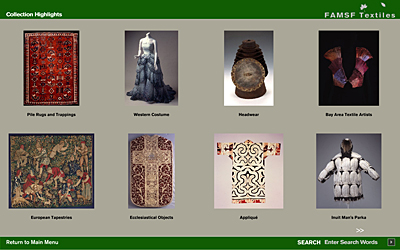

Fig 5: The Textiles interactive intro screen

The major sections of the textiles interactives are:

- Collections highlights, including European tapestries, Bay Area textile artists, fans, footwear, and Iban ceremonial skirts.

- Objects on view, such as special exhibitions and objects found in the Textile Center’s study drawers.

- Techniques such as embroidery, felt, resist dyeing, and lace techniques.

- Geography: a detailed map interface allows users to navigate by geography. The geography interface also understands the concept of regions. Textile curators can create a region (such as Central Asia) and associate countries with it.

- A visually annotated glossary of textile terms, where images, video or Flash files can be attached to any glossary item. Objects can be attached to glossary terms, providing examples drawn from the collections database.

- Links to more than 12,000 related textile objects in the FAMSF collections at the de Young and the Legion of Honor.

Fig 6: Textile Collection Highlights.

Objects can be interrelated in Sitebots. For example, a series of tapestries may be linked together, or a ceremonial headdress and cloak can be connected.

The interactives are synchronized with the same collections databases that provide content for FAMSF’s Web site. When she wishes to add new collections information to the interactives, the textiles curator uses an import tool within the CMS to import from the 4D collections database. The system synchronizes the new data by matching against accession numbers to add new records and update existing information. Once in Sitebots, the curator can use any of the more than 12,000 textile objects to modify or create new sections of the interactive.

Technology Approach

In our overall technical approach to the interactives, we also followed a Web-based model. One Web server in the museum’s basement delivers all content to the two iMac work stations in the Textile Study Center (the same Web server delivers content to the signage as well, but more on that below).

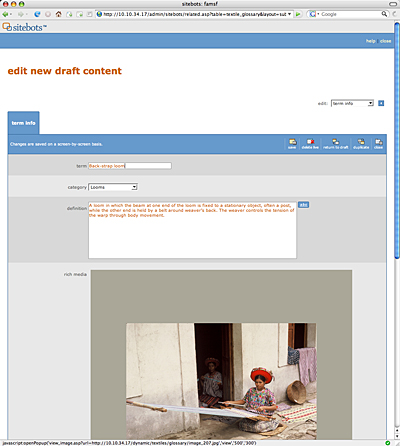

The textile interactives are data-driven Flash applications. The Flash is generated by the CMS; no Flash programming is required for content management or updating. Curators use Sitebots, a browser-based CMS to update and manage content on the interactives from their desks.

Fig 7: The Textiles Glossary entry for “back-strap loom.”

Fig 8: The corresponding page in Sitebots.

We built on our current technical infrastructure, expanding our existing CMS to accommodate the new tools and content of the interactive. This enabled us to develop the interactive at relatively low cost. Equally important, we built on existing systems and workflow. The interactives were developed with Mediatrope, an outside firm, but they can be supported by the museum Web master.

Future Directions: Returning To The Web And Experimenting With Handhelds

Since the de Young opened in October 2005, Textile curators have modified and expanded the content on the interactives significantly. In addition to considering new features, like an enhanced search function and new video tours, we’re also thinking about new ways to distribute the content on the interactive. The interactive has greatly increased the collections information available to visitors to the textile study center, but it is not lost on us that this educational content is currently limited to those who visit this small space within the museum.

We imagine that the content on the interactive will migrate back to the FAMSF Web site. Our original decision to build the interactive on a Web-based foundation will serve us well as we complete the circle: mounting a version of the interactive on the FAMSF Web site will cost relatively little. Moreover, because the interactive and Web site are powered by a single CMS, publishing the interactive’s content on the Web site will not increase the maintenance or content management burden on staff.

We’re also considering creating a second Flash skin for the interactive and publishing it to a handheld device for use as visitors tour the textile galleries. The CMS that curators use to create and manage content on the interactive will also publish to a handheld. Our collections database provides real-time information about an object’s location, and so the handheld would provide interpretive content about only those objects on view. Finally, the single Web server that delivers content to the interactives in the study center and the electronic signage could also easily serve content to a handheld system.

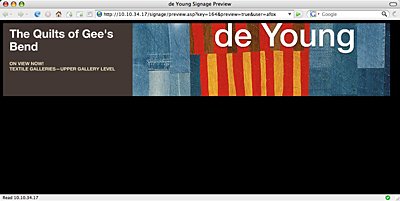

Electronic Signage

Origins

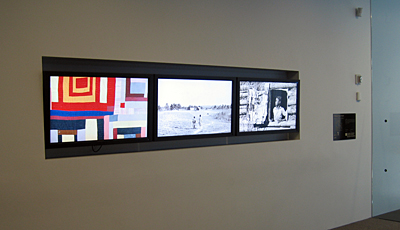

Perhaps the most prominent digital resource in the new de Young is the electronic signage program. Consisting of three separate installations of large-screen monitors, the electronic signs serve as ever-changing billboards alerting and informing museum visitors about exhibitions, programs, events, and collections.

Fig 9: The electronic signage in the lobby of the new de Young

At the time of initial planning, such displays were seen in only a handful of museums, and were generally experimental in nature. They were, however, seen in ever-increasing numbers in trade-shows, retail stores, and public facilities such as airports. In fact, from our temporary offices near San Francisco’s Union Square we could walk to see nearby examples installed in Macy’s and the Apple Store.

Initially, the primary impetus for developing the electronic signage lay in the visual impact of the illuminated, moving images displayed on the large screens. Many ideas, including that of a large “video wall” installation wherein an entire section of wall, from floor to ceiling, would be covered in video displays showing animated content, were floated but eventually rejected for reasons of technological and financial practicality and practicability. Eventually, the idea of a sort of animated billboard was chosen as the ideal model for the electronic signage - sweeping animations that would intrigue and excite visitors about the permanent installations and special exhibitions offered by the museum, and in keeping with the sophisticated and state-of-the-art environment of the new de Young.

After site visits - to museums, trade shows, and other venues - and extensive research by members of the development team (including myself, FAMSF Chief Graphic Designer Ron Rick, Curator Karin Breuer, and Mediatrope principal Ethan Wilde), we developed a set of initial goals and requirements for content, software, and hardware.

As an initial experiment to gauge public response to electronic signage, a 40-inch LCD monitor was set up in a prominent public space at the Legion of Honor, the de Young’s sister museum. A set of animations promoting exhibitions, resources such as the museum store and café, and the new de Young’s imminent opening was run in an ongoing loop. Public reaction was extremely favorable, with the most positive comments about the animated exhibition previews. Interestingly, opinions as to non-exhibition content were polarized between those who thought the information moved by too quickly and those that felt it wasn’t displayed long or frequently enough!

Ultimately, the decision was reaffirmed to head in the ‘animated billboard’ direction and reject the ‘airport signage’ model. Due to the varying locations of the electronic signage arrays in the new de Young, none of which were immediate to obvious visitor-oriented points such as admission and information desks, there was no guarantee that visitors would see, and more importantly, stop and read a great deal of information on the screens. Animated, cinematic information, on the other hand, would attract visitors to the screens where they would be exposed to information in a more efficient manner.

Software was another issue. There are numerous turn-key products readily available: among them Omnivex, Scala, and Clarity CoolSign. These proprietary applications focus mainly on presenting large quantities of data information in the ‘airport signage’ model; Omnivex, for example, is geared mainly to display information for financial institutions.. More importantly, these products are stand-alone applications unable to interact with our current CMS, thus necessitating a duplication of data and staff effort to program the signage. Price, too, was a consideration. While not overwhelmingly expensive - various out-of-the-box setups were all in the low to mid five-figure range - we found that it was more cost-effective to invest a similar amount in a custom application that met our specific needs well. Another factor was cross-platform compatibility; all of these proprietary applications are Windows-only, and our development team all use Macs.

Finally, the signage hardware itself had to be determined. Several competing technologies were considered: plasma, projection, and LCD. Projection, while offering large screen size for a relatively reasonable price, was the first option rejected due to space considerations in the new de Young. Plasma was also considered, but rejected for several reasons: picture quality was more suited for television than computer graphics, and the screen would burn in and require replacement in a relatively short time. We heard from one institution that had learned this lesson the hard way and needed to replace all of their plasma screens only two years after installation. LCD monitors were decided upon as they possessed superior graphics qualities, and, though more expensive than plasma screens, would be more cost-effective in the long run.

Equipment

The monitors eventually decided upon were NEC LCD4610 46-inch LCD units, with a maximum screen resolution of 1366 x 768 pixels. The project was originally designed around 55-inch units that were under development by NEC and due for release in May of 2005, but these units ultimately were ‘vaporware’ due to technical development problems at NEC, and the smaller units were selected with a promise by NEC’s North American representative for a partial exchange of the existing units for the 55-inch models when they became available. A 57-inch model (NEC LCD5710-BK) was finally made available in limited quantities in November, 2006.

Each array of three signs is powered by a single Hewlett Packard workstation that runs the Flash-based signage application. Each workstation is equipped with two high-end Nvidia Quadro 4000 graphics cards that work in tandem. The three displays do not operate independently and are in effect one large monitor of 4,080 x 768 pixels. An additional HP workstation serves as the central server for the electronic signage, allowing content to be repurposed in all three locations.

Fig 10: The electronic signage display outside the de Young’s Herbst Exhibition Galleries.

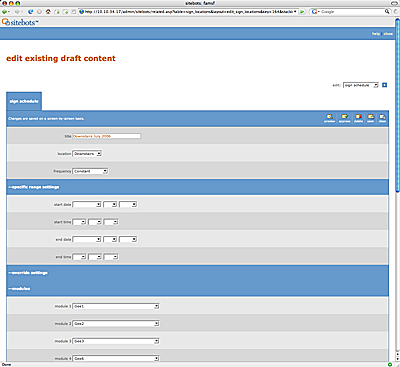

Software

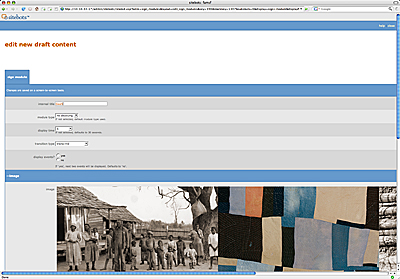

Like the above-mentioned textile interactives, the de Young’s electronic signage follows a Web-based model. Driving the signage is a Flash application that takes advantage of Flash’s ability to access and display dynamic content. Content is input into the appropriate fields in the Sitebots CMS user interface, as it would be for the Web site, and when published, the information is sent to the main electronic signage server where it is then accessed by the client workstations. Additionally, the electronic signage program interacts with the de Young Web site’s events calendar. If configured, the electronic signage will display calendar events at the appropriate date and time, drawing the information from the main FAMSF Sitebots Web server, which pushes updated content to the electronic signage server on a nightly basis. This eliminates the need to update the signage as a parallel calendar system.

Fig 11: When entering a calendar event into Sitebots, museum staff can opt to make the event details available for publication on the signage.

While the signage system, like the textile interactives, is served locally, the FAMSF Web site and CMS are hosted at a large San Francisco data center.

Each signage location functions on its own separate schedule, and draws from a menu of individual ‘modules’ which are Flash animations lasting from 10 to 120 seconds. Each module consists of images, text and an ‘animation toolbox’ of a variety of pre-set animation types, allowing images to pan horizontally or vertically, up or down, left or right. Additionally, there are a number of animated transitions - wipes, fades, and dissolves - that can be selected and deployed between modules for a seamless appearance. All modules are stored in the central signage server and are available for use at any or all of the locations in the building. Schedules for each location consist of up to 20 modules, which run in a pre-defined order as dictated by the schedule. If needed, special schedules can be created to automatically override existing schedules based on date and time. These are especially useful for corporate building rentals and special events.

Fig. 12: The content creation screen in Sitebots where museum staff create new content for the signage.

Fig 13: The CMS generates the Flash animation on the fly from text and images entered by museum staff. You can preview the Flash animation before making the new signage content live.

Fig 14: Screen shot of the “location scheduling” tools in the CMS that are used to program the signs.

Assessment

The electronic signage system launched with the opening of the new de Young in October 2005. As we’ve used the system day-in and day-out over the past 15 months, the successes and lessons of the project have become increasingly clear.

Overall, the program has been a huge success. Although the signs were initially afflicted with display problems due to various installation issues, the display quality at present is very high. The system is, as mentioned previously, extremely flexible, with nearly unlimited configurations for each location. Development costs were relatively low, and maintenance costs have been nearly non-existent. In fact the most persistent problem experienced is an occasional system crash on the workstations. It takes only a few minutes to get the displays back up and running. Maintenance to the signage program itself can be done in ‘real time’ without disrupting the currently playing program. The transition from old to new program is done in a seamless manner, with the new program taking over at the end point of the old. Maintenance of the system is possible by non-technical staff, although design skills and a familiarity with digital media terms and concepts are definitely recommended.

The biggest success by far has been the use of a familiar CMS interface to program the signage and manage signage content. Integrating information from the Web site, on the other hand, has been successful on a technical level, but not necessarily from a content perspective. At this time we’re still attempting to determine how best to show this information on the current signage deployment. The reason? The Web and the signage, although sharing much technologically, are two very different delivery platforms.

The signs are animated promotions for exhibits, collections and special events, and as such are fundamentally promotional rather than informational. In contrast, the Web site calendar is almost purely informational, providing date, time, location, cost and a brief description of museum events. In other words, the signs are movie trailers to the calendar’s movie listings. As a result we’re still working out the best way to promote specific events on the signs. That said, having event information available for easy publication on the signs is a great boon.

Most of the differences in the two platforms have to do with visitor expectations and behavior. With the Web, visitors can guide themselves through the content of a Web site in a random path determined by where they want to go. Content can be viewed for any length of time and in almost any order, limited only by a Web site’s navigation. The signage, on the other hand, relies on a static program to display its content. Visitors doesn’t know what’s coming up or what to expect, and we as programmers have no idea what information any specific visitor wants or needs. Therefore, it is better for the signage to be promotional rather than informational. Certainly the situation would be different if the sign were something purely informational; for example, something installed near the entrance to an auditorium or theater that informed visitors of the events scheduled in that space only. Our installation, on the other hand, serves to promote the entire museum.

The initially developed templates and animations allow for the creation of new Flash animation modules that are consistent with the museum’s branding guidelines. The ease of creation and flexibility of the system has led to requests from museum management to deviate from the templates and create more custom graphics for the signage modules, resulting in less and less use of the template. From one perspective, this is a clear indication of the overall success of the system. But we’re still seeking the best balance between standardization and customization as we learn to work within this new medium.

Lastly, developing animated Flash presentations for the electronic signage requires that the Web master don an additional hat and play movie director. This is a new role, and it presents both practical (how much of my job is developing signage animations?) and design (how do you design effectively for signage audiences?) challenges.

Future Directions

Perhaps the most important outcome of these projects is that we now have a strong, tested platform upon which to expand. Possible future enhancements to the system include new display templates to vary the styles seen in the current electronic signage modules; dynamically integrated exhibition information, much like that seen on the FAMSF’s Web site; scheduled publication and ‘unpublication’ for future dates; and an integrated system for image and digital asset management.

Cite as:

Fox, A., Within These Walls: Putting Web-Based Resources to Work in the New de Young Museum, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2007 Consulted http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/fox/fox.html

Editorial Note