Dick van Dijk, Waag Society, The Netherlands

Abstract

Waag Society and the Archive of the province of Drenthe have developed Operation Sigismund. Operation Sigismund is an experiential learning environment: a magic realist representation of an archive, combining game elements, narrative elements and learning goals in a clearly defined physical space within the Archive’s building. The project brings the archive to life for children in primary schools. The children get pulled in by an exciting story and have to protect an important private collection against all kinds of dangers – like dampness, fire, and ink corrosion – and solve the mystery of Sigismund. The context, contents and rationale of the project are described.

Keywords: archive, adventure game, narrative, education, experiential learning, design, play

1. Introduction

The diary of an 18th century Dutch aristocrat by the name of Sigismund van Heiden Reinestein is the starting point for the educational adventure in the basement of the monumental building of the Archive of the province of Drenthe (in Dutch: Drents Archief).

The concept of an adventure game is used to create an experiential learning environment in which the private records of Sigismund are naturally embedded. Sigismund van Heiden Reinestein (1740 – 1806) was chamberlain and confidant of William V, stadtholder of The Netherlands, and as such in charge of managing the household of the prince. His archive consists of thousands of unique personal and political records, government documents and correspondence, all held by the Archive of the province of Drenthe.

The diary of Sigismund, presented to pupils aged 10-12 at the start of the 1.5 hour adventure, suggests that he is aware of the whereabouts of the lost seal of William V. The seal is important because it functions as symbol of the authority of the prince. The seal might have been entrusted to Sigismund in the dangerous times when William’s reign was disputed by The Patriots (a political faction in the Netherlands that struggled for the removal of the corrupt Stadtholder regime and its nepotistic way of governing, eventually leaving William V no choice but to flee the country).

In the adventure the pupils go on their own journey to reconstruct 18th century life, including the actions of Sigismund, and to locate the abandoned royal seal.

The adventure is a combination of computer-based and physical interactions connecting pupils to their local heritage in an exciting way. The solution to the mystery is to be found in Sigismund’s records that they have to preserve and organize themselves in order to be able to reconstruct Sigismund’s story. The pupils work in groups of three on conservation activities such as the examination, documentation, advice on treatment, and preventive care of these historic records.

Fig 1: Portrait of Sigismund van Heiden Reinestein (1740 – 1806). The portrait was painted in late 18th century.

Fig 2 : Building of the Archive of the province of Drenthe in Assen. This is where the adventure is built.

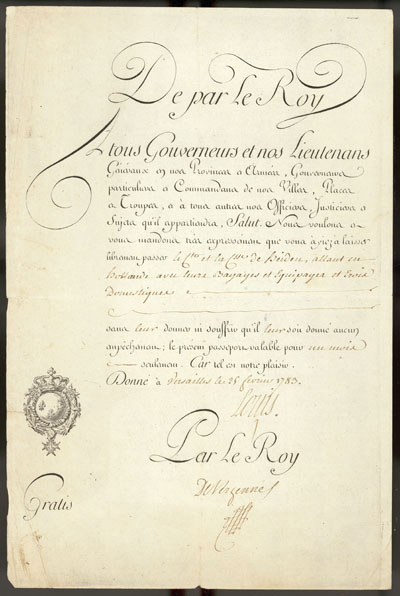

Fig 3 : Record from Sigismund’s personal archive: travel permit signed by the French king Louis XVI allowing Sigismund to travel freely through France to fulfill his diplomatic duties.

Fig 4 : Record from Sigismund’s personal archive: envelope folded from paper as was customary in the second half of the 18th century. The letter has been sent to Sigismund’s private residence; all Sigismund titles are used in the address but there’s no physical location mentioned.

Fig 5: Print of the seal of William V, prince of Orange. Image used courtesy of the Dutch Royal Archives.

2. A Playful Experience

Play is a structuring activity, the activity out of which understanding comes. Play is at one and the same time the location where we question our structures of understanding and the location where we develop them. (James S. Hans; quoted in Rules of Play)

In their projects, Waag Society researches the possibilities of gaming and playful learning for education. Our main questions in this area are:

- Is it possible to use simulations and 'serious gaming' to create authentic learning experiences?

- In what way do virtual and physical gaming experiences influence each other?

- How can we combine the cognitive, affective, kinetic, strategic and problem solving skills that are addressed in a game environment in formal education?

- What is the role of narrative in an experiential learning environment?

Though Operation Sigismund might not instantly be regarded a game by most (computer/video) game enthusiasts, as there is no adrenaline rush, no explicit game levels and no competitive element, I will refer to game (related) research to describe the users’ experience, bringing our design and development choices to the surface. Though intrinsically connected, users’ experience is described from three different viewpoints: the game experience, the narrative experience, and the learning experience. In verbalizing these viewpoints, the book Rules of Play by game experts Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman has been especially helpful.

2.1 The Game Experience

2.1.1 A Magic Circle

We have taken the basement rooms of the building of the Archive of the province of Drenthe as a clearly defined physical story space or games space in which the story develops. It is centered on the figure of Sigismund, with the adventure adding to the experience of the story.

The pupils’ game experience within Operation Sigismund consists of:

- a theatrical setting;

- a narrative steering the flow of the adventure;

- an educational design underlying the actions and assignments;

- interaction with intelligent, tangible objects;

- goal-oriented interaction;

- a clear outcome.

This game space can be characterized as a magic circle the pupils enter when descending into the basement, formally stepping into the game, “temporarily enacting a world within the ordinary world” (Klabbers, 2006). The term ‘magic circle’ is used by Johan Huizinga (1951) to describe an ‘isolated’ setting, an alternate reality, in which rituals and special rules apply to all participants, whether they are witches or judges. Although the magic circle is just one of the examples in Huizinga’s list of ‘playgrounds,’ the term is used by authors Salen and Zimmerman as “shorthand for the idea of a special place in time and space created by a game” (2004).

As all our participants are players and there is no interference from an outside reality, a special place indeed is created: literally by entering the basement, and metaphorically when encountering the diary of Sigismund and the quest it symbolizes.

The fragment of the diary directs the pupils’ attention instantly towards the quest, fostering an open or “lusory attitude” (Bernard Suits, 1999; in Rules of Play) towards playing the game. In addition, we have taken the rituals and rules of the professional life of an archivist as the rules for our game. The pupils do not consciously pretend to be archivists; they remain themselves. Their task is to assist the Archive in categorizing, preserving and studying the records, ultimately leading them to the treasure.

Fig 6 : Ground plan of the basement rooms that were used to create Operation Sigismund. The basement is divided into 5 different spaces.

Fig 7a and 7b : Views of basement rooms before the makeover into the Operation Sigismund setting.

Fig 8 : Design for the reception room in the basement of the Archive of the province Drenthe. Each of the 5 basement rooms has its own identity. Here the pupils first see the diary fragment that triggers the adventure and hear about the historic figure of Sigismund.

2.1.2 Adventure Game

In game research, the concept of adventure games is mainly referred to as a genre of video and/or computer games typified by exploration, puzzle solving, and interaction with game characters, with a focus on narrative rather than reflex-based challenges. Though some of these characteristics apply to Sigismund, here the adventure is rolled out in the physical space, with a narrative structure that gives the archive, its role and its collection a logical and appealing context, thus creating stimulating ground for learning. Our challenge here was to balance the game elements, the narrative experience and the learning goals.

The driving element of our ‘game’ is a treasure hunt or puzzle hunt. With Sigismund’s records, the pupils hunt for clues related to the mystery. They have to work as true archivists and discover the possibilities an archive offers to reconstruct exciting stories of the past.

Salen and Zimmerman cite Bernard Suits who in his book Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia defines games as inherently inefficient: often there are more efficient ways to achieve a goal. Why engage in an excruciating game of boxing when you can also shoot someone if your goal is to make that someone stay down for 10 seconds? In the case of Operation Sigismund, it would have been an option to explain to the pupils more formally how an archive works, but here the constructionist learning theories and individual learning styles come into play, assuming that learning from personal experience has more enduring learning outcomes.

2.2 The Narrative Experience

2.2.1 Game as Drama

“Within narrative we order and reorder the givens of experience. We give experience a form and a meaning.” (J.Hillis Miller; quoted in Rules of Play)

Game designer LeBlanc uses eight categories of games describing the kinds of experiential pleasure the players derive from playing games, as a means to go beyond the concept of ‘fun’ (1999). Though categories like Sensation (games as sense-pleasure), Fantasy (game as make-believe), and Narrative (game as drama) may overlap, the category Narrative strongly connects to Operation Sigismund.

The narrative experience starts when the pupils enter the basement rooms and take in all the visual cues from the rooms. The formal start of the 1.5 hour adventure for the pupils is a fragment of the diary of Sigismund, suggesting that Sigismund was aware of the whereabouts of the lost seal of William V. (Though some diaries of Sigismund are available as part of the Archive’s collection, this particular fragment was created by us to frame the narrative.)

The Archive’s educational staff explains to the children where they are and introduces the pupils to their tasks ahead. They function as external narrators – not being actors in the story, but 'standing outside' the story – at the beginning of the adventure and highlight the elements of the quest, creating an atmosphere of suspense and urgency.

The narrative experience consists of:

- a narrative goal

- a narrative object (Sigismund’s diary)

- internal and external characters

- suggested uncertainty of the outcome

- a narrative space

The adventure can be described as an embedded narrative (LeBlanc, 1999) because Sigismund’s story is pre-generated narrative content that exists prior to the players’ interaction with the game (as opposed to emergent narratives that arise from the process of playing; these are the players’ own stories). The narrative gives reason to the players’ action and provides the major story arc for the game. The adventure adds more layers to the pupils’ experience of the story.

Because of the pre-generated narrative and the fact that Operation Sigismund uses a more or less hierarchical educational design in which the pupils knowledge and skills are gradually being built, the linear structure became a given for the development of the adventure. Still, where possible we have created some flexibility, using a content management system that allows us to create different time-based sequences of the assignments (in these sequences also, issues such as time-played and time-left play a defining role as the adventure has to be finished within 1.5 hours).

Along the way the children learn about the archive, and about life in the 18th century, their own local history, and life at the Dutch court. By interacting with the workstation computers and physical objects in the basement rooms, the pupils are steered towards the final clue, hidden in one of the archival records.

Fig 9: The final clue to the adventure is hidden in the encoded message. The encoded message is historic, but the meaning of it is unclear. We have used the idea of encoded messages, which were common in the diplomatic communication in the 18th century, to give closure to the narrative.

2.2.2 Systems of Meaning

As Salen and Zimmerman say, game play takes place within a representational universe, filled with depictions of objects, interactions and ideas out of which a player makes meaning. Author/ designer/ writer Brenda Laurel’s standpoint that the key to the success of a dramatic representation is that all of the material used is drawn from the circumscribed potential of the particular dramatic world (Laurel, 1993), is equally true for physical interfaces such as ours, not only visually, but also dramaturgically.

Design-wise we borrow and sample heavily from Sigismund’s portrait and his time. But we also incorporate the physical movements and the routines within an archive into the physical space. The overall atmosphere is magic realist. The basement rooms in which the learning activities take place are a mix of high tech and 18th century salons, as shown in the design illustrations in this document.

When first browsing through the records of Sigismund’s archive, we, as adults with an active interest in history, were impressed by the nature of the records in the archive and all the historic associations they evoke, especially when we experienced the tactile quality of the old materials (without the expected white protective gloves!). To our surprise, the target group kids with whom we did our initial research shared the same fascination while studying, for a serious amount of time, what was for them an unreadable French record. They ‘felt’ the importance of the documents. Based on these initial findings we decided to stay as close to the historic feel and its narrative quality as possible, rather than focusing on computer based gaming.

The basement rooms we have created are as follows.

- The Reception room with seating for 24 pupils (the average size of one local class) is where the adventure starts. The fragment of the diary is displayed in the center of the room. A selection of (facsimile) records from Sigismund’s personal archive is presented to the pupils in leather saddle bags and travel boxes, as though they have not been touched for ages;

- Two Workstation rooms with in total eight workstations is where the groups of pupils get their cues after logging into the Digital Archivist system, and where the pupils return to collect their materials. Though the Digital Archivist is not visualized as a game character, the software engages in dialogue with the pupils, functioning as core mechanic for the advancement of the overall story;

- The Scanner room is where the pupils can access tools to help them in their archival tasks and in their larger quest.

- The Archival room is where the records need to be placed, accurately catalogued, where the Cabinets give feedback to the pupils, where the room’s temperature and humidity conditions can be adjusted, and where the historic stories from Sigismund can be heard.

The rooms suggest history, but all the interior components are also objects for storage and organizing, familiar to an archive. In line with the ability of children to make ‘something’ out of ‘nothing’ we created a seemingly disorderly array of boxes and crates (where stories and treasures may be kept) that with a little imagination becomes an 18th century salon. Within this magic circle, special meanings accrue and cluster around objects and behavior. In effect, a new reality is created, not only ‘defined by the rules of the game and inhabited by its players’ (Salen, Zimmerman), but also defined by the theatrical sphere. This new reality also allows us to introduce ‘intelligent’ objects to the space.

Fig 10 : Design for the Archival room in the basement of the Archive of the province Drenthe

Fig 11 : Design for the Workstation room in the basement of the Archive of the province Drenthe

2.3. The Learning Experience

2.3.1 Augmented Space

The phenomenon of play involves a paradox, a condition in which something is both real and not real at the same time. (Russian psychologist Levigotsky; citation from Tony Graham, 1999)

Although games have been played in real-world spaces for millennia, Lev Manovich states that people in the 1990s were more fascinated by new virtual spaces made possible by computer technologies. In his essay “The poetics of augmented space” (2002), he suggests that the decade of the 2000s might be all about physical space filled with electronic and visual information, as computers and network technology more and more enter our physical spaces. Especially his definition of tangible interfaces – treating the whole physical space around the user as part of human-computer interface (HCI) by employing physical objects as carriers of information – and smart objects – object connected to the net; objects that can sense their uses and display ‘smart’ behavior – seems applicable to Operation Sigismund. The use of nearfield technology such as RFID and iButtons in combination with network technology allows us to create or suggest intelligence in doors, cabinets and electronic devices. Though Manovich uses the definition of electronically augmented space to connect (visualized) new and existing data spaces to physical space, we use the augmented objects and interfaces to steer the pupils’ activities and further empower the learning experience, placing the user inside the experience.

The intelligent objects are:

- enhanced digital scanners that not only digitize the archival records, but also help establish authenticity of, age of, and damage to the records;

- enhanced cabinets that help organize the archival records by giving feedback on the records offered, but also broadcast the content of (some of the) records through built-in audio (audio scapes);

- two electronic displays for conservational conditions such as temperature and humidity in the archival room.

The objects and eight workstations (computers) are connected in a local network. On the workstations the specifically developed ‘Digital Archivist’ interface is installed.

Fig 12 : Design for the Scanner room in the basement of the Archive of the province Drenthe

Fig 13 : Work in progress at the Archival room in the basement of the Archive of the province Drenthe

Fig. 14 – 16 : Work in progress in the basement of the Archive of the province Drenthe

2.3.2 Educational Design

‘Whether gamespace is more real or not than some other world is not the question. That even in its unreality it may have real effects on other worlds – is.’ (McKenzie Wark, 2006)

Although Wark in this quote from Gamer Theory is referring to a different game space (simulation games such as the Sims, 2006) the point he is making is very valid for our project. Experiential education (or ‘learning by doing’) is the process of actively engaging students in an authentic experience that will have benefits and consequences. Students make discoveries and experiment with knowledge themselves instead of hearing or reading about the experiences of others. Students also reflect on their experiences, thus developing new skills, new attitudes, and new theories or ways of thinking (Kraft & Sakofs, 1988).

As children can easily relate to modern technology, the choice for a game-based educational learning experience was easily made. We incorporated the formal learning goals of the primary school into our educational design: learning goals such as letting children experience an archive as containing intriguing stories rather than ‘stuffy’ documents, and further experiencing that these documents are worth preserving, are a treasure in themselves.

The resulting educational design of Operation Sigismund consists of:

- formal learning goals

- educational content

- assignments

- narrative actions and narrative descriptors

- embedded games

- suggestions for a pre-visit (on-line) preparatory lesson and a post-visit reflective lesson.

To organize the educational content and assignments, the Archival staff proposed the Dimensions of Learning model (Marzano, 1988). The Dimensions of Learning model encompasses five critical components of learning:

- maintaining positive attitudes and perceptions

- acquiring and integrating knowledge

- extending and refining knowledge

- using knowledge meaningfully

- developing productive habits of mind

We used the model to create a more or less hierarchical working structure for the educational content and assignments. The assignments vary from open questions and multiple choice questions to the performance of physical tasks and creative assignments, in such a way that we first facilitate the acquisition of contextual information, go on to build and refine the pupils’ knowledge and skills, and then create opportunities for them to apply their knowledge and skills (be it in the digital or physical space). The relationship between the computer environment (Digital Archivist), the intelligent objects, and the physical space lets the pupils repeat certain actions in an alternate setting (applying a set of skills, first, derived from a digital assignment, secondly, in the physical space, and the other way around).

The educational design combined with the narrative structure provides the learner with enough context to play the game. And because the total experience affects the learner not just on a cognitive level, appealing to more than one learning style, it can lead to better retention (which should be further tested).

The assignments function as narrative descriptors, identifying objects and events in the larger narrative, and following the representational logic of the larger narrative. They could also be described as narrative actions (Manovich, 2001) as they trigger the events of the narrative. In the assignments, the children take on the role of deputy archivists, in both computer-based and physical actions, mimicking the rules and routines of the Archive. The pupils work in groups of three to facilitate understanding and dialogue among them, but also to give them the possibility to naturally take on different roles within their group.

Some of the digital assignments can be described as embedded games, such as a memory-game-inspired setting in which the pupils have to match damaged archival records and their probable causes. Another example is a creative assignment that lets the pupils create their own computerized design of William V’s seal, based on the information they have acquired so far on the theme of seals and what they represent.

“It’s natural for players to reconstruct a story from a game play experience, but it is not inevitable, nor is the story the game” (Costikyan, 1999; quoted in Rules of Play), but for the educational experience, the retelling and sharing of the game experience is critical. For this purpose we have created two moments, one at the end of the game (after the pupils have located the hidden seal), the other afterwards, back at school where the pupils discuss amongst themselves what they have experienced and what they have learned from it. In addition the pupils take home their own (printed) Operation Sigismund Certificate as a basic record of their experience (with personalized results of some of the creative assignments) ; the teacher can build upon these in future lessons.

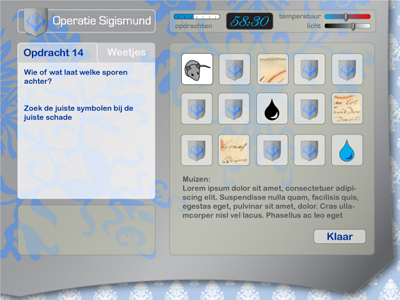

Fig 17 : Design for the interface of the Digital Archivist. The Digital Archivist is the computer-based system that steers all pupils’ actions throughout the game.

Fig 18 : Screen design for the interface of the Digital Archivist: the pupils have to match damaged archival records and their probable causes before they can advance to studying the condition of the real records.

3. User Participation

As part of our working methodology, teachers and pupils of local primary schools have participated in the project as a development panel. Based on the personal preferences, needs, wishes and feedback of these individuals, we engage in an iterative process of designing concepts, mock ups, demos and, ultimately, tested prototypes. The designers’ intuition and the users' behavior here are in a constant dialogue.

The Operation Sigismund development panel has given us feedback on mood boards, narrative scenarios, (interaction) design sketches, exemplary assignments, and hard- and software mock-ups. They even had to pretend walking through the basement rooms following chalked outlines of the interior elements. Their feedback and enthusiasm is an important factor in our development process, called ‘users-as-designers’.

Between February – April 2007, the schools will participate in three sequential pilot settings where we test the understanding, the logic and the timing of the adventure. Based on their input, we will further optimize the adventure for opening in May 2007.

Fig 19 : The pupils that are part of the development panel at work in one of the basement rooms.

Fig 20 : The development panel being introduced to the routines of the Archive.

4. Partners

Operation Sigismund is a project from the Drents Archief in Assen (http://www.drentsarchief.nl) and Waag Society in Amsterdam (http://www.waag.org). The project is supported financially by local and national funding organizations. The educational aspect of the project is tested against a development panel consisting of target group teachers and pupils.

Waag Society is an acknowledged Medialab where, apart from R & D, there is room for experiment with new technologies, art and culture. Partners come from all parts of society: universities, and also large companies take part in the design and development projects.

Waag Society and the Drents Archief believe that new media for learning purposes mix well with the daily routine of young people, as youth culture today is more and more dominated by (communications) technology and high tech applications – such as mobile phones, games and on-line chats. An experiential learning environment should incorporate youth culture and let pupils play, communicate, create, cooperate, experience and learn, in ways that suit them, inside the classroom, out on the street or in cultural institutions like archives and museums.

References

Graham, Tony (1999). The child is always a head taller when he plays. Speech at Doors of Perception 5 Conference.

Huizinga, Johan (1951). Homo Ludens. Haarlem: H.D. Tjeenk Willink & Zoon N.V.

Klabbers, Jan H.G. (2006). The magic circle: Principles of Gaming & Simulation. Rotterdam/Taipei: Sense Publishers.

Kraft, D., M. Sakofs (Eds.) (1988). The theory of experiential education. Boulder, CO: Association for Experiential Education.

Laurel, Brenda (1993). Computers as Theater. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

LeBlanc, Marc (1999). “Feedback systems and the dramatic structure of competition”. Speech at Game Developers Conference

Manovich, Lev (2001). The language of new media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Manovich, Lev (2002). The poetics of augmented space. Publication at http://www.manovich.net

Salen, Katie, Eric Zimmerman (2004). Rules of Play. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Marzano, Robert J. (1988). Dimensions of Thinking. Publication at http://www.mcrel.org/dimensions/whathow.asp

Wark, McKenzie (2006). Gamer theory. Publication at http://www.futureofthebook.org/gamertheory/

Cite as:

Van Dijk, D., Operation Sigismund: Bringing and Archive into Play , in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2007 Consulted http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/vanDijk/vanDijk.html

Editorial Note