1. Introduction and Social Context

Schools, especially primary schools in Italy (K1 to K5), and Cultural Institutions (e.g., museums) more and more need to cooperate. As far as schools are concerned, there are at least two different motivations for this increasing interest toward cultural institutions:

- Schools are paying increased attention to promoting local culture in a more effective way.

- Schools are stepping up support for learning styles different from simply reading books; therefore, visiting museums, searching out materials, organizing activities around the exhibits, etc. are welcome, and more prominent activities.

As far as Cultural Institutions are concerned, the following are a couple of motivations:

- For many of them, schools are, or are becoming, an important segment of their “market”. In many archeological museums in Italy, for example, the majority of visitors (especially in the morning) come in student groups.

- Strengthening ties with children, and generating in them interest in the institution, may trigger stronger ties with their families, and therefore promote a better sense of community (Werger 1999) .

Still, in this scenario there are also some problems. A visit to a museum does not per senecessarily create a deep impact on students. Teachers must organize activities before and after the visit: before, to prepare the children properly, and after, to consolidate the interest and knowledge generated during the visit. Cultural field trips, however, are often considered boring by the students and a distraction from the curriculum by their parents. In addition, the educational apparatus that is organized by a cultural institution around its collections or exhibitions may be at odds with or not easily integrated into the learning process organized at school.

In this paper, we propose that technologies (e.g., Multimedia, Web, Search Engines, Podcasting.) can help in a number of ways:

- They can be a basis for cultural heritage-oriented educational activities that seem interesting and “modern” to children who are surrounded by technology in their every day life and who easily find conventional museum exhibits or printed material on cultural heritage subjects too traditional and “old fashioned” (Ardito 2007).

- They can effectively support the integration of educational activities organized by cultural institutions and those carried on at school, providing stronger motivation for follow-up classroom activities that are crucial for consolidating the information and the stimuli derived from the on-site visit to a cultural institution.

- They can be used to generate “visible results” that are rewarding to children and well appreciated by their families.

In the rest of this paper, we discuss the lessons learned in a project carried on with twenty-four students aged 10-11 at a primary school in Milan. The children first experienced cultural heritage in a physical setting during a traditional visit to the Milan archeological museum and to the few Roman remains in our town. Then the children brought their experience into the classroom, extending and amplifying it by means of technology. They built a multichannel hyperstory around their physical experience of cultural heritage, exploiting Web resources, and, above all, created an on-line hyperstory using the authoring tool 1001stories, which was developed at our lab and presented at MW2007. Our tool is briefly introduced in this paper, and the reader is referred to Bolchini 2007 for details. Here, we focus on the activities carried on by the children during the project and discuss the outcomes from the perspectives of all involved stakeholders – children, teachers, families, and cultural heritage institutions.

2. A Hyperstory Authoring Tool: 1001stories

In general terms, “hyperstory” means “hypermedia story”; i.e., anything that has a non linear structure and encompasses an emotionally and symbolically charged discursive narrative to generate and sustain meaning (Antle 2003), (Benford 2000). A multi-channel hyperstory is a hyperstory which is delivered on different channels - in our case, Web, CD-ROM, and iPod.

1001stories (Bolchini 2007) can be defined as a web-enabled application framework (Garzotto 2005), (Samis 2004), (Schwabe 1999), for multichannel hypermedia storytelling. As such, it provides an application “skeleton” that captures the essential features of multichannel hyperstories and can be customized to produce a specific hyperstory.

1001stories does not intervene in the creative job of designing good narrative structures and building story contents. We rather address the process of

- translating conceptual narrative structures into a suitable interactive format;

- filling these structures with multimedia contents, and

- delivering the resulting hyperstory on different channels.

Our main purpose is to make this overall process as simple, cheap, and fast as possible. 1001 stories is fast to learn, quick to help authors complete a story, and easy to use, hiding the complexity of the underlying implementation. Everything - from building the narrative structures, to inserting or updating multimedia contents in the narrative units, to page publishing, to CD-ROM compilation, to podcasting - is intuitive and doable with few clicks. In addition, 1001stories is delivered together with a set of Guidelines that include a suggested workflow (i.e., a structured collection of activities for building a hyperstory in an efficient way), and a set of content production suggestions for the development team.

The information architecture of our hyperstories is a simple tree-like structure composed of a predefined set of node types (see figure 1). The node types are Cover, which acts as “Home” and introduces the story; Ancillary Information, which may contain arbitrary information about the story ( e.g., about author(s), the development team, institution or company or organization, sponsors, credits, acknowledgments, etc.); Story Topic (Topic for short), which represents a “piece of a story” of any semantic nature, depending on the application domain (e.g., describing facts, persons, characters, events, anecdotes, places, objects …); and Story subtopic (Subtopic for short), which denotes a sub-subject of the related topic. The content format of each node type is pre-defined for each delivery channel. On the stationary channel, for example, a Topic or a Sub-Topic is composed (see figure 2) of a title, a subtitle, a descriptive text, an audio narrative, and a dynamic visual media object – a sequence of images, a (2D or 3D) video, or an animation – synchronized with the audio narrative. The audio and the dynamic media start playing automatically when a user enters the corresponding Topic or Subtopic.

For the last generation of iPod, a Topic or Subtopic is a “movie”; i.e., a video + audio unit, while for previous iPod versions or for other MP3 players, we support the creation of audio-only hyperstories.

Fig 1: Information and Navigation Architecture of a 1001story hyperstory (on Web or CD-ROM)

Fig 2: A Topic (‘Roman Terms in Milan’) of a 1001story hyperstory (on Web or CD-ROM)

Navigation links exploit three navigation patterns (Garzotto 1999):

- Index (from a node to each node in a group of nodes, and back)

- GuidedTour (sequential bidirectional navigation)

- Automatic Guided Tour (forward sequential navigation in which the activation of the “next” link is triggered automatically by the system). In our design, next-link automatic traversing is triggered by the end of the sound comment.

On the Web and CD-ROM versions of the story, all the above navigation patterns are combined to support different navigation ‘styles’: manual navigation, automatic-short navigation, automatic-long navigation. In manual navigation, the user is in control of the navigation, and can traverse all index links or guided tour links available in a node. Automatic-short and automatic-long navigation exploit the automatic guided tour patterns respectively among Topics, and among Topics and Subtopics. In automatic-short navigation, the system takes the user from Topic to Topic, triggering the next Topic when the audio narrative of the current node is over. The user can remain passive, listen to the audio narrative, watch the animation, read the textual narration, and enjoy the story flow from topic to topic (still with the possibility of suspending and re-activating it at any time). In automatic-long navigation, the paradigm is the same, but the narrative flow now traverses the linearization of the Topic-Subtopic tree structure: the system takes the user from a Topic to the first Subtopic, from here to the next Subtopic, from the last Subtopic to the next Topic, and so on. To make the experience more engaging and customized to the actual user’s needs, the navigation style is adaptable: users can select the most appropriate navigation style according to their preferences (and modify that choice at any time) - see figure 3.

Fig 3: Cover Page of a Hyperstory – navigation style control buttons

Hyperstories on the iPod (figure 4) device are views of their counterparts on stationary environments that customize both content and navigation structures according to the display and interaction capability of the delivery platform.

Fig 4: Enjoying a hyperstory on the iPod during a cultural visit

Navigation is based on index and automatic navigation patterns only, and a hyperstory is shaped as a set of video play-lists; i.e., sequences of (video +) audio items that are (dis)played automatically one after the other as the play-list is activated by the user (see figure 5).

Fig 5: A hyperstory Topic on the iPod

Fig 6: Hyperstory structure on the iPod

A very friendly interface - see figure 7 - supports the access to and the use of the following functional components: Data Entry, Previewer, and Multi-delivery Generator.

The Data Entry is a simple control panel enabling the user to edit the editorial plan of the story (i.e., to decide the Topics and Subtopics of the story), to enter content for each element (i.e. title, text, images with captions and audio file), and to perform all needed changes (see figure 7). The physical creation of multimedia content pieces (e.g., images, videos, sounds, descriptions) takes place outside the 1001Stories framework, using appropriate multimedia authoring tools.

At any moment during the development process, the Preview allows developers to visualize what has been produced so far, as it will appear to the end user. In this way, the developer can immediately check the quality of the work (e.g. the impact of the content, or the graphics) and make any desired improvements. In situations of collaborative authoring, the Previewer facilitates the creation of a shared understanding within a development team of what is achievable, and of the impact of different authoring choices.

The Generator produces and publishes the final applications (for the different delivery channels), once every element of the story has been set and specified.

Fig 7: 1001story Interface (Editorial Plan)

3. The Learning Process

Roman civilization is a key topic in the program of the last year of Italian primary school. To anchor children’s understanding of this broad subject to something more “tangible” and closer to their experience, the theme for our project’s hyperstory was focused on Milan during the Roman Age. Indeed, Milan was one of the capitals of the Roman Empire (Second and Third centuries A.D.), and a few remains are still visible in town (a tower from the circus is embedded within the Archeological Museum) and/or are exhibited at the Archeological Museum. The hyperstory was therefore titled “Milano Romana Tecnologica” (i.e., “Milan at the time of the Roman Empire presented through Technology) - hereafter called “Roman Milan”

The activities of the class were organized in four major phases:

- In-the field cultural heritage experience of Roman Milan

- Traditional classroom work.

- Technological Training

- Development of the Hyper-story.

In-The-Field Experience And Classroom Work

The teachers organized a one-day school trip during which children were exposed to cultural heritage in a "traditional way". They visited a cultural institution (the Civic Archeological Museum), underground or outdoor (few) remains of Roman Milan in different quarters of the town, and areas where no ruin is visible today, but that hosted important places of cult or public life during the Roman period (e.g., the huge thermal baths were in an area where a subterranean garage is located today). They also walked around the downtown streets where the structure of the Roman streets (“cardo” and “decumanano” maximo) still emerges from the modern urban texture. In this way, learning about Ancient Romans in general, and Roman Milan in particular, was “situated” i.e., anchored in a context that was meaningful to the children. During the trip, they took many pictures (figure 8) and collected printed material; e.g., postcards and booklets at the museum.

Fig 8: Taking pictures of the statue representing Emperor Costantino

To consolidate the children’s understanding of what they had seen, teachers proposed conventional classroom activities back at school; such as group discussions, study using school books and the printed material collected at the museum, and creation of short individual narratives about the trip.

Technological Training

Afterwards, a team from HOC-LAB helped children (and teachers) to understand the characteristics of the product they were expected to create with technology, and to build the (limited) technological skills needed to use 1001stories to create multimedia contents.

Working in small groups in the school computer lab, the children practised with image scanning and manipulation, digital sound recording, file system organization, image import from digital camera, and on-line search engines. In order to better understand the content organization and the navigation-interaction paradigms of our hyperstories, the children explored examples of existing hyperstories. Finally, children and teachers learned how to use the 1001stories authoring tool.

We were confident of the easy-to-learn quality of the tool, but still were surprised by the fact that, after a brief explanation of the main operations, the average learning time was 17 minutes, with a 12-minute record and a 26-minute worst case.

Development of the Hyperstory

For the hyperstory development process, the children were organized into groups of three, where the different technological skills were blended.

Before breaking to start work, the whole class discussed the choices of Topics, and they came up with the following list: “Milano Becomes the Capital of the Roman Empire”, “The Archeological Museum”, “The Forum”, “The Theatre”, “The Streets”, “The Thermal Baths”, “The Circus”, “The Amphitheater”, and “Saint Lawrence Basilica”.

After the assignment of one Topic per group, the children started the hyperstory production work (Figures 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15). They integrated the material collected during the on-site trip with textual and visual contents retrieved from the Web (using a search engine) and from school library books, and with their own drawings (the latter, as discussed later, was their own innovative idea). They scanned the printed material and imported pictures from their cameras. They wrote the narrative texts and recorded their readings of the different narratives. Tasks like the identification of what to do and the execution of the different tasks were interspersed with discussion and brainstorming - within the group, among groups, and with the teachers. They made a number of revisions during the production process, and did final quality checks before delivering the final version (available on: http://www.policultura.it/kids.htm).

Fig 9: Discussing contents on paper within a group (left) and with the teacher (right)

Fig 10: Collecting Digital Contents: Searching on Google (left) and scanning books’ images (right)

The children gave a very creative contribution to the “design of the experience”, proposing original ways of carrying on the workflow as we originally conceived it in our “Guidelines” for 1001stories, and introducing new activities with and without technology that our design team had not experimented with in our previous projects.

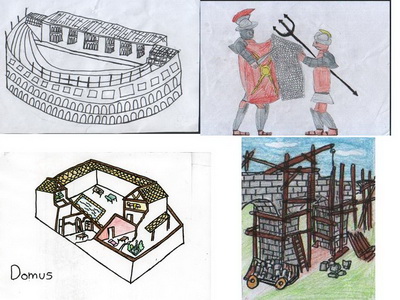

During the content production phase, for example, it was the children’s idea to create drawings to complement the existing material, and they spent a significant amount of time in this work (Figures 11 and 12).

Fig 11: Building contents: drawings

Another of the children’s ideas concerns the use of “tangible” tools to brainstorm on and to specify the editorial “plan”; i.e., the structure of Topics and Subtopics. Differently from what we observed in adults or older students, who typically build the editorial plan directly on the computer, these children decided to use a paper poster and a set of post-its of different sizes and colors - big light blue post-its to represented a Topic (e.g., “The Terms”) and smaller yellow post-its to represent a Subtopic (e.g., “What Romans used to do at the Terms”), as shown in figure 13. They collaboratively created different versions of the poster, including the proposals from the different groups. During this dynamic “brainstorming” work, children, teachers, and our design team engaged in discussions/critiques/reflections on the various solutions, adding, moving, and removing post-its to define the topics and subtopics and the proper order among them, truly collaborating and elaborating on one another’s ideas.

Fig 13: Creating the editorial plan

Furthermore, the children found a way to engage their families in the project: they asked parents to visit Milan Roman with them together during the weekend, since they wanted to refresh their memories of the various places (they wanted to be sure of what they were writing in their narratives!) and to take further pictures of places and monuments related to the Roman period.

Finally, the children contributed to identifying patterns of teamwork. Even when each group was responsible for a specific topic and each member of a group for a specific subtopic, the overall process was strongly collaborative, both within and among groups. The allocation of tasks within a group was based on different criteria. In some cases, children distributed the work according to the nature of the contents: some children focused more on visual material, others on textual contents. In other cases, the criterion was task-oriented: some children were devoted to content search (on the Internet or in books); others to drawing; and still others to content digitalization. An original example of within-group collaboration concerns the creation of audio. In our previous 1001story experiences, involving only adults or high school students, hyperstory developers typically allocated a single speaker the task of reading an entire topic or subtopic. In contrast, these children decided to split each single narrative into pieces, and to assign the reading and audio recording of each piece to a different group member. This solution was particularly time-consuming. Children read and read again each topic or subtopic before being satisfied with the voice and tone of all actors, and spent quite a lot of effort merging the pieces into a single audio track (see figure 14). Still, the final effect was very nice, and much more engaging than having just one speaker.

Fig 14: Collaborative audio-recording

Inter-group collaboration occurred during the whole development cycle, much more intensively than we expected. We initially configured the tool in “individual-view” mode, so that each user could see and update only his group’s portion of the story (i.e., his group’s topic and subtopics). We planned to offer the shared view mode – which allows all users to see and update all topics and subtopics - only at the end, to avoid having any child intentionally or unintentionally destroy another’s work. It turned out that the children wanted to see what the others were doing right from the very beginning, to compare their group’s progress with the other groups, and to share visual material among groups. Thus, after a couple of sessions, we provided the shared-view mode for all groups, to support inter-group collaboration.

Fig 15: Collaborative Quality Check

When the last subtopic was finally composed and revised, and a preview of the entire hyperstory was generated, the design team expected to be finished, but we were wrong. The children were so engaged in the project, so excited about their story, and so conscious of the value of their experience, that they decided to do some extra work: to tell “their” story of the whole process, and to add it as a new Topic in their hyperstory. To describe this new Topic, they adopted an original metaphor, presenting the project work as a cookbook recipe – the “Milan Roman” digital meal (see figure 16). The content resources needed for the hyperstory were introduced as “ingredients” for the recipe, and the needed activities as to-do steps to prepare and cook “Milan Roman”. They decided that the Sub-Topics of the new Topic should describe each group’s “views” of the project. These narratives highlight the children’s emotional perception of the experience. Some groups narrated, for example, how surprised they were to discover the hidden past of their town, and how much they liked to show their story on the Internet to their family. Other children invented rhymes or funny songs to describe their feelings. All groups also took new pictures and created new drawings for describing themselves, their group, and their work for the purpose of this new section (figures 16 and 17).

Satisfaction and Educational Benefits for Children, Families, and Teachers

All the children enormously enjoyed the overall experience. They were enthusiastic about the work, and in some cases “forced” the teachers to bring them to the computer lab outside the scheduled sessions. They always asked about "doing more". To assess satisfaction, as well as qualitative observations we used (very carefully) a small questionnaire: 90% of the kids gave the maximum score (“Very much”) to the question: “How much did you like the project?” and only 10% scored it “It was ok”. In addition, a good number of the free comments were quite enthusiastic (“I would like to do it again!!!” “I wish I had it [the tool] at home thus I could continue my work there!”).

From an educational perspective, we achieved a number of benefits. Obviously, children learned about technology. They became naturally and very playfully familiar with a number of basic Web and multimedia technologies. Since the teachers were not very familiar with computers, in most cases children had to "teach their teachers" and to explain the different operations to them.

But the children also improved their knowledge, attitudes, and skills to different levels (Bloom 1964). Having a special purpose while visiting the museum, they paid much more attention than usual, and learned more from their on-site exposure to cultural heritage. The need to organize a narrative within a strict format forced the children to work cooperatively, in order to define the conceptual structure, to prioritize items and to synthesize material. This was beneficial both for better understanding the subject matter and for acquiring and/or developing a number of skills (e.g. group work, narrative organization....).

Teachers estimated that the experience induced much higher achievement of the above learning benefits, when compared with conventional activities carried on at school to address similar learning goals. Teachers were skeptical at the beginning, but became progressively more and more enthusiastic. They advertised the project within the school in such an positive way that this year, four different classes from the same institute wanted to participate in the project; and our team is currently working with over ninety students aged 9-11 on different themes related to Milan’s cultural heritage.

Finally, parents were also quite enthusiastic, surprised, and very proud of their children when they realized that their kids were so involved, and when they received the final production as a CD-ROM.

4. Conclusions

At first sight, the experience of the Roman Milan project may look similar to other experiences of producing digital content. However, there are some specific aspects to be considered:

- The strictly technological activities were not the ones requiring the most effort. Understanding the historical and cultural issues, developing a body of knowledge and relating it to a physical experience, organizing content, synthesizing concepts, finding or creating information resources – these were the main concerns.

- The (very synthetic) format of 1001stories’ hyperstories forces children to express themselves with a few words, and therefore to focus on what they have really understood.

- When children visited the Museum and then went around the city listening to the tour guide and shooting pictures, they had a special purpose and therefore were very excited and motivated.

- The cultural value (in a strict sense) of the production is negligible, as is always true for productions from school. It has, however, a flavor of “freshness,” and is a pleasant souvenir of something that involved a museum and a class of children (using their faces and their voices).

From a Cultural Heritage point of view, we see a number of positive effects of the approach pursued by our project:

- The visit to the museum was considered by the children a special event, something that they still remember (after one year) – not the standard reaction to conventional exposure to cultural heritage; i.e., visits to cultural institutions.

- The subject matter was well internalized by the children. An informal test we used with a group of project participants highlights that after one year, they still remember most of the content used to create Roman Milan.

- Families became engaged in what was happening, and as a consequence, became interested in the subject; i.e. Milan at the time of the Roman Empire. Some families were “forced” by their kids to visit the Archeological Museum and different Roman places in town. As this museum is quite small, it was unfamiliar to most parents, who visited it for the first time when they were brought by their children.

- The museum received special attention from the teachers, and teachers rated it highly among other teaching experiences.

Will the families be better visitors of the museum? Will the children become frequent visitors of the museum once adults? Will their interest in antiquity remain when they grow? Will the school maintain stronger ties with the museum in the future?

We can’t honestly answer all these questions; also, we are fully aware that we cannot easily generalize from just one experience. Since, however, we have a strong feeling (and some evidence) that something interesting happened, we have started a number of initiatives following this first attempt. First of all, we opened our competition “POLICULTURA” (from the Greek πολύ = "many", and the Italian “cultura” = “culture”), to primary schools (in the previous edition, it was reserved for high schools). The POLICULTURA competition asks schools at all levels - from primary to high schools - to use the 1001stories tool to create hyperstories similar to Roman Milan. By the end of January 2008, we had more than 200 classes registered, from all Italian regions - almost 4000 students involved – and 50% of the schools are primary. This is an interesting result on its own.

As we mentioned earlier, we are repeating an experience similar to Roman Milan with four more classes in the same school whose students volunteered to participate. The themes will include ‘Renaissance Art in Milan’,and ‘The Navigli Old District’. This time the monitoring of the impact from a Cultural Heritage point of view will be more systematic and more quantitative. We will try to better understand the cultural impact on children, teachers and family, and we will also organize a monitoring “one year later” study to verify what learning survives over time. We hope that in a reasonable amount of time (let’s say for the next school year) we will be able to come up with a complete “package”, including 1001stories, a model of project organization, tips about what to do and not to do, in order to offer to Cultural Institutions and schools technological and methodological tools for more effective cooperation.

5. Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Archeological Museum in Milan, and to the teachers and children of Primary School “Nolli Arquati” in Milan - class 5D (year 2006-07) - who enthusiastically participated in the project. A special thank to Aldo Torrebruno and to the whole HOC team.

6.References

Ardito, C.(2007), M.F. Costabile, R. Lanzilotti, T. Pederson. “Making dead history come alive through mobile game-play”. In CHI '07 Extended Abstracts, April 2007. ACM.

Antle, A.(2003). “Case Study: The Design of CB4Kids’ Story Builder”. In the Proceedings of 2003 Conference on Interaction Design and Children (Preston, England).

Bloom, B.S. (1964), B.B. Mesia , and D.R. Krathwohl. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York: David McKay, 1964.

Benford, S. (2000) et al. “Designing Storytelling Technologies to Encourage Collaboration Between Young Children”. In Proceedings of CHI 2000. The Hague, Amsterdam: ACM Press.

Bolchini, D. (2007), N. Di Blas, and P. Paolini. “Instant Multimedia”: A New Challenge For Cultural Heritage. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Museums and the Web 2007: Selected papers. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Available: http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/diBlas/diBlas.html

Crocker, J.(2005). “Active Learning Systems”. In ACM Computers in Entertainment, Vol.3 N.1, Jan.2005.

Garzotto, F. (1999), P. Paolini, D. Bolchini, and S. Valenti. "Modeling by patterns" of Web Applications. In Proc. International workshop on the World-Wide Web and Conceptual Modeling. WWWCM'99, Paris, 293-306 Nov 1999.

Garzotto, F. (2005) and L. Megale. “Towards Enterprise Frameworks for Networked Hypermedia: a Case-Study in Cultural Tourism”. Proc. ACM Hypertext’05, Salzburg (A), Aug. 2005, ACM Press.

Samis, P. (2004). “Making Sense of Modern Art at Five”. Museums and the Web 2004. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics.

Schwabe, D. (1999), G. Rossi, L. Emeraldo, F. Lyardet. “Web Design Frameworks: An approach to inprove reuse in Web Applications”. Proc. WWW99 Web Engineering Workshop, Springer Verlag, 1999.

Werger, E. (1999). Communities of Practice, Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge Press.