Introduction

The Smithsonian American Art Museum hosted the Alternate Reality Game (ARG) “Ghosts of a Chance” between July 18 and October 25, 2008. The project also included a module version of the game, which is run on a recurring and ongoing basis in the museum. Alternate Reality Games are interactive stories that take place in the real world and in real-time, using primarily the Internet but also often including phone, e-mail, and in-person interaction. They encourage community involvement as players work together to solve puzzles and codes, investigate narratives, interact with in-game characters, and coordinate real-life and on-line activities (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alternate_reality_game).

We decided to base the ARG in the museum’s Luce Foundation Center for American Art, an innovative visible storage and study facility that displays around 3,300 objects from the collection (http://www.LuceFoundationCenter.si.edu). Multimedia computer kiosks offer information on every artwork and artist represented in the Center, allowing visitors to engage in as much or as little interpretation as they choose. A dedicated staff and budget allow us to present a variety of low cost, informal public programs that strive to show the visitors something new, or encourage them to look at the works in a different way. The overarching goal of the Center is discovery. Whether it’s a detail of an artwork that you never noticed before, the story of the artist who made the work, or new connections made by displaying the artwork with other similar pieces, we want you to leave the Center feeling as if you got something out of it. With this in mind, when the game designers CityMystery approached us about using the Luce Foundation Center as the real world platform for an ARG, we agreed that it would be a wonderful use of the facility and the narratives that already exist around the collections.

There were some initial concerns, of course, particularly as ARGs were a very new and different concept for the museum staff to grasp. How, exactly, would we benefit from this venture? Would the museum be at risk from thousands of unexpected visitors? Would we compromise the museum’s credibility by supporting the fiction of the game? And would the traditionally bureaucratic processes of the Smithsonian allow us to keep up with the fast-paced, player-led nature of ARGs?

We concluded that the game would benefit the museum by taking our name and our collection to new audiences, particularly those who didn’t normally visit art museums but did participate in on-line games. We were hopeful that the on-line aspect of the game would become viral, but acknowledged that we had no way of controlling or predicting this. We decided not to be too concerned about an overload of physical visitors because the Luce Foundation Center space is able to accommodate varying sizes of groups, and all of the art works are behind glass. Additionally, for us, too many visitors would actually be a great problem to have to deal with! We did determine a plan to carefully monitor the on-line activity leading up to the live event, so that if it looked like thousands of people were going to show up we could put appropriate measures in place to secure the collection. The concerns over compromising the museum’s credibility were overcome by agreeing to brand everything game-related with the game logo. This did not spoil the fiction for the players, but allowed us to let everyone know after the game exactly what museum-created content was “fake.”

Fig 1: Ghosts of a Chance Logo.

Finally, early support from managers at the Smithsonian, both within the American Art Museum and across the entire Institution, allowed us to take chances that would not have otherwise been possible.

Game Overview

The narrative of the game told the story of two student curators, Daisy Fortunis and Daniel Libbe (played by actors), who came to work for the American Art Museum. Through late nights spent together in the museum, they discovered that they had something in common: they were both haunted by restless spirits. Daisy was haunted by a ghost named Blanche, and Daniel by McD. Two other spirits, named The Reverend and WhatFor, were also causing trouble in the museum. Players initially discovered this through the characters’ profile pages on Facebook and mySpace. In addition, Daisy and Daniel obsessively filmed themselves in and around the museum talking about (and to) the spirits, and posted the clips to a variety of sites, including YouTube. Interested media outlets agreed to hide clues in articles about the game. For example, ABC.com concealed a spooky audio clue in an on-line article, and the Smithsonian Magazine included a full-page color photo complete with embedded clue in their nationally-distributed print magazine. The challenge for players was to uncover the story of the spirits and determine what they could do to help.

Evaluation

The game-play was not linear and grew to be quite complex. For these reasons I am going to break it down into three main sections for the purposes of the evaluation: The Pre-Game, which ran from July 18 to September 8; the Main Game, which ran from September 8 until October 25; and the Ongoing Game, which we continue to run. For each, I will give an overview of key game events, and then evaluate success based on player feedback, statistics, and the outcome compared to our expectations. For the purposes of the evaluation, “hardcore players” are defined as those who participated in the on-line ARG discussion forum Unfiction (http://forums.unfiction.com/forums/). The term “casual players” includes everyone else, whether they actively participated in game tasks, or just watched the story unfold.

Pre-Game (July 18 – September 8, 2008)

Fig 2: Bodybuilder Craig Torres Poses at ARGFest-o-con. Photo courtesy Konamouse

The annual event for hardcore ARG players “ARGFest-o-con” was scheduled for July 18, 2008. While our game was not scheduled to launch until September, we thought it was the perfect opportunity to plant a teaser and hopefully start people talking. CityMystery hired the national-level bodybuilder Craig Torres, covered his chest and back with elaborate henna tattoos, and had him gatecrash the event while flexing his muscles to music. Within a couple of hours, a discussion thread had started on Unfiction and photos were up on Flickr.

Hidden in the tattoos was an image of an artwork from the Luce Foundation Center and the words “Luce’s Lover’s Eye.” When players looked this up on Google, they found the Luce object page, in which we embedded a hidden link to the Ghosts of a Chance (GOAC) Web site.

Fig 3: Screen Shot of Pre-Game Web Site (http://ghostsofachance.com/goac_eyes/)

The Web site invited them to e-mail an image of their eye or their lover’s eye and call a phone number. The message on the phone included a quote from Shakespeare’s Macbeth, mention of September 8th (the game’s launch) and asked players to record the “Double double toil and trouble” incantation. Over the next few weeks we added a couple of clues to the game site and secreted another in an ABC.com article (http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/Story?id=5490189&page=1).

Overall, we were pleased with the results from the pre-game. The speed at which players responded to the teaser was overwhelming, and we definitely maintained their interest over the next few weeks. Comments on the forum included:

So uh, this stripper totally bogarted the end of Steve Peters' presentation by dancing into the main conference room and flexing his henna'd muscles for a while. He had some words written up near his left shoulder, so I did a bit of Googling and found something strange at this Smithsonian webpage. (Unfiction User: krystyn)

You know, in thinking about it, this doesn't make any sense... Why would the Smithsonian send a stripper to a place like ARGFest to get this going? I mean, think about it, a borderline government agency sending a stripper to a convention in a hotel? That would be front page news on The Drudge Report! (Unfiction User: Nighthawk)

I'm sending my eye in tonight. It's only taken me this long because my head was still reeling from the body builder interrupting our little geek-fest. (Unfiction User: faeryqueen21)

We received over 150 images of eyes and 256 calls in response to the initial tasks. Players enjoyed pondering the cryptic nature of the information revealed and came up with several very interesting possible scenarios. The ongoing on-line buzz after July 18 far exceeded the museum’s expectations, as we did not predict so much conversation around the event. Our concerns at this point centered on how to maintain this positive attention up to and throughout the Main Game.

Main Game

Six weeks of Mystery (September 8 – October 25, 2008)

At 12:01am on September 8, the game Web site changed from the eye-collecting site to the official game site.

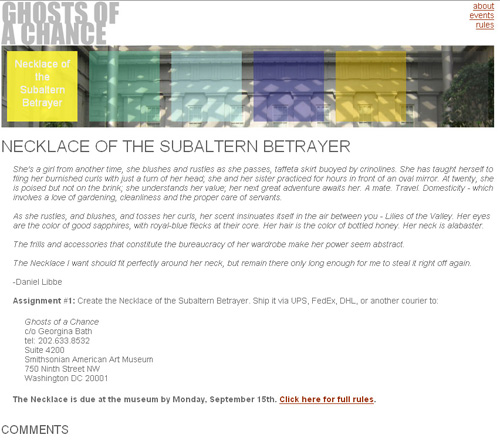

Fig 4: Screen Shot of Home Page on September 8 (http://ghostsofachance.com/main_site/)

The site included an overview of the story so far, links to Daisy’s and Daniel’s social media profiles, and details of the first assignment. Players learned that in order to unlock the story of Daisy and Daniel and their resident spirits, they had to create a series of artifacts and mail them into the museum. The museum would catalog these and ultimately display them in an exhibition curated by Daisy and Daniel. Each artifact had quite mysterious requirements that were directly connected to the narrative.

Fig 5: Screen Shot of Assignment #1.

The fact that we were asking players to create artifacts and mail them into the museum was probably the biggest challenge that we faced during development of the game. These objects would not be accessioned into the collection; we just had to create the illusion that they were for the purposes of the story. However, this obviously caused several concerns.

- Where would we receive the artifacts? We did not want to have them delivered to the museum itself, because the receipt and movement of artworks involves far more people and paperwork than should be necessary for this project. We worried about confusion when security and facilities staff were faced with what might appear to be a collection object. We decided to have them mailed to our office building, a block-and-a-half from the museum proper. An additional problem was the complexity of the Smithsonian mail system, which includes a time-consuming central sorting system. To avoid this, we had to request that players use couriers to send the artifacts. But couriers can be expensive, so we hoped this would not prohibit people from participating.

- Would the inclusion of these artifacts in our on-line collection and in-gallery kiosks confuse visitors who were not playing the game? We added a watermark of the game logo to each photograph, and text on the interpretive labels associated the artifacts with the game and included a link to the game Web site. In addition to addressing the potential confusion, we hoped that this solution would draw more people to the game.

- Were we creating unrealistic expectations? We worried that participants who submitted artifacts might think that their work was becoming part of the Smithsonian. To solve this, we included the following disclaimer in the game rules: “Please note that these artifacts will form part of the Ghosts of a Chance initiative, but will not become part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum's permanent collection.” We also made sure that similar text was included in all official materials about the game.

- What would we do about storage if we received a large number of artifacts, or individual artifacts that were huge in scale? As with all museums, we never, ever have enough storage space to fulfill our needs. We decided to create limits on the size of the submitted artifacts (they had to fit within a shoebox) and concluded that to avoid putting pressure on any other department, my office would become the storeroom. The game designers also agreed to have an alternative plan for storage in place, should we receive more objects than could realistically fit in my space.

With these discussions complete and concerns addressed, we waited to see what would arrive in the mail. The deadlines for the artifacts were extremely tight; players had just a few days to come up with an idea, make it, and get it to the museum. By monitoring on-line conversations and talking to players through e-mail and phone, we knew that the association of the Smithsonian brand was putting additional pressure on them, as they wanted to make sure their work was of high quality.

Over the six weeks and six assignments, we received thirty-three artifacts from fourteen players. While these numbers may initially seem small, the quality of the submissions was extremely high, especially considering the tight deadlines and somewhat obscure requirements. The need to use a courier didn’t seem to put people off (except one player who lived in Hawaii) but it did result in a few submissions arriving late, since some players were unwilling to pay the fees for 1- or 2-day delivery. Of the people who created artifacts, seven were crafters who participated because of the opportunity to make something, five were hardcore players, and two were unknowns. (Some hardcore players may also be crafters).

Fig 6: “Someone To Watch Over Me” by Jenny Klostermeyer

Fig 7: “Sealed Vessel for an Unknown Woman” by Joanna Barnum

The feedback from the players about the hands-on aspect of the game was very positive:

So it's a combination between a puzzle and an art project. This is extremely cool. (Unfiction User: The Mirror)

An internet collaborative art display in a national museum? Is it me, or is this very frigging cool! (Unfiction User: Tenshi Akui)

I'm so glad the art world is getting involved--I've been working on some local ARGart of my own. Totally jumping in on this one! (Unfiction User: ETCetera)

We were also pleased with the attention from casual players that this element of the game had attracted, and not just from those who had contributed artifacts. Visitation to the game Web site and interaction on Facebook increased, and we started to hear more from people who were not necessarily familiar with ARGs.

Fig 8: Screen shot of player-created artifacts in museum’s on-line collection

Alongside the progression of the artifacts and the narrative, interaction between in-game characters and players was taking place in social media spaces. Daisy and Daniel posted regular videos to YouTube, Facebook, and mySpace that showed their gradual descent into madness caused by the spirits.

Fig 9: Screen shot of video clip on YouTube

They also interacted with players and real museum staff on Facebook. One player (not a staff member!) created a “Ghosts of a Chance” group on Flickr, in which players collected artifact images and museum staff posted images from the live events.

At this point, we noticed a small reduction in interest from the hardcore players, based on our observations of the Unfiction forum. Daisy’s and Daniel’s story was detailed and creative, and the videos were wonderfully believable, but there didn’t seem to be much player discussion around the content. We knew that people were reading the story and watching the videos, and some players even interacted with Daisy and Daniel on Facebook, but they didn’t seem interested in figuring out the mysteries that we presented. We did maintain a solid core of hardcore players that actively followed the game to its conclusion, but I was disappointed that we lost a fair amount of the original interest. Conversely, the main game succeeded in drawing in a wide audience of players who did not have any prior experience of ARGs.

I initially drew two possible explanations for the decrease in hardcore interest. One was because we went “official.” The pre-game Web site was somewhat haphazard in appearance and wasn’t really designed further than a simple header. The eye images were posted in a single column down the page, and reshuffled with each refresh. After September 8, the main game Web site was elegantly presented and claimed affiliation with the Smithsonian on the front page. I speculated that the players who preferred the underground, mysterious nature of the pre-game content may have lost interest once it was opened up to casual players and became more mainstream. Secondly, the narrative of Daisy, Daniel, and the spirits was unlocked by the creation and delivery of artifacts, but further than that it did not give the players anything to do. There were subtle connections to be made between elements in the story and happenings in the real world, but for the most part it was just a case of following along with the story as it progressed. It is possible that the lack of tangible tasks led hardcore players to move on to other things.

Detailed feedback from hardcore player Scott Myers proved one of these theories wrong, supported the other, and presented a couple of other valuable insights:

- The Smithsonian name did not

scare people away. In fact, it did the opposite as people were intrigued

and surprised by the association. However, Myers speculated that the brand

was a contributing factor in why we did not receive hundreds of artifacts:

“When you are scribbling doodles to write to some abstract character in a funny little game no-one will ever see, it’s easy to come up with something. But when the SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION (spoken in big impressive voice) asks you to submit a portrait or something, it’s a little more intimidating.” - Myers agreed that there was

less for the players to do once the game began, but he emphasized that

this was not necessarily a bad thing. “A good story is better than a

hundred bad puzzles.” He also clarified exactly what was taking place in

Unfiction, which was primarily “Meta conversation,” or conversation about the game itself (who was

running it, how it would unfold, etc.) rather than what was going on in the game. He noted:

“Meta discussions can be useful to gauge interest and awareness, but they are by no means an indicator of actual positive enthusiasm, levels of interaction, or even the quality of the game.” - Myers felt that the game did

not fully succeed in carrying the momentum from the high energy teaser

through to the game launch. He suggested that an e-mail (or some other

type of “loud and clear message”) introducing the players to Daisy,

Daniel, and the ghosts would have been helpful during this time. He also

noted that the connections between the artifacts and the narrative were a

little challenging, though he enjoyed the story and thought that the

artifacts were a “terrific way” to get people involved.

“What Ghosts of a Chance did well was invite participants to take part in the exhibit – essentially becoming part of the exhibit themselves. [...] Sometimes a painting is just a painting. But more often, there is a story that is waiting to come out and be told. [...] People should be encouraged to discover these relationships, and see exhibits in a new light.”

One decision that we did make early on was that it was okay to acknowledge this project from the outset as an ARG. Many ARGs follow the “This is Not a Game” approach, in which “one of the main goals […] is to deny or disguise the fact that it is even a game at all” (Szulborski, 2005). It was clear that the story of Daisy and Daniel was not “real”; however, we hoped that we would succeed in blurring the line between the reality and the fiction. We did not reveal until the game was complete that the two young characters were entirely invented. Daisy and Daniel did not work for the museum and they did not actually exist; their real names were Alex Cohen-Smith and Scout Seide. I took on an alternate personality for whenever I interacted with Daisy and Daniel, and became quite a scary supervisor with little patience (something that I hope I’m not!). The museum created fictional blog posts, tweets, Facebook content, letters, and a press release (http://ghostsofachance.com/main_site/ GOAC_press_release.pdf), and supported the temporary inclusion of player-created artifacts into the on-line collection. We definitely succeeded in maintaining this fiction through to the final event on October 25, as several players on the day commented to staff members that they hadn’t realized Daisy and Daniel were hired actors. The overarching response from participants, both on-site and on-line, was one of surprise that an established institution like the Smithsonian had been willing to relinquish a little control over its content in order to fabricate the story.

In addition to all of the on-line activity, we organized two live mini-events for the players during the six weeks of official play. We thought it would be interesting to take the game play outside our walls and integrate other Washington D.C. sites, providing variety for the players as well as taking advantage of some of the other cultural experiences that the city has to offer. The first took place on September 20 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Players were treated to a behind-the-scenes experience of the anthropology department with Dr. David Hunt. At the end of the tour, they were led into a room with seven skeletons.

Fig 10: Dr. David Hunt in the Forensics Lab

Five were identified, and two were not. Dr. Hunt walked the group through the process of identifying race, gender, age, and cause of death with the five identified remains, and then challenged everyone to investigate the two others. He even provided (fake) police forensic reports for each body. The story of the two skeletons showed that they belonged to the mysterious characters Blanche and McD, the very same entities that were causing Daisy and Daniel so much trouble!

The second mini-event took place on October 4 at the Congressional Cemetery. Patrick Crowley, Chair of the Board of Directors, took players on a fascinating tour around the tombstones that included the history of the cemetery as well as a wealth of trivia about the famous people who had been buried there. By exploring tombs and crypts, players found a skull, a Morse code key, black-out paper, and a flashlight. They soon noticed two strange figures in the distance, flashing a light at the group. A small group of dedicated players (with a bit of prompting from the game designer) concluded that they could use the tools to communicate with the figures. The primary participants in this included an artifact-creator, and a couple of casual players who had been following the story and were drawn to the cemetery event because it was “nearly Halloween.” Through the conversation with the spirits, participants learned that they were the characters The Reverend and WhatFor, and that they wanted “rest.”

Fig 11: Players at the Congressional Cemetery

The intent of these mini-events was to attract a small number of players who would post photos and information to the various sites associated with the game. The events met with mixed success. The Museum of Natural History requested that we limit the number of people on the tour to twenty. To ensure this, we decided to invite players through an Evite, which was also publicly accessible. Ten people signed up. The evening before the event, however, someone mysteriously hacked into the Evite and sent out a series of reminders with the incorrect date and time. We don’t know who sabotaged the invitation or why, but we were only able to fix it and send out a new reminder a couple of hours before the event was due to begin. This meant that just a handful of people came to the tour, and none of them were hardcore players so the content did not get posted on-line. Museum staff posted the photos and police reports to Facebook and Flickr, but it didn’t really get as much attention as we had hoped.

The Congressional Cemetery tour was more successful, with a couple of players posting photos and sharing the story of the ghostly encounter. However, fewer people than we had expected commented on the links between the mini-events and the narrative.

Over 6,100 people participated on-line during the course of the game (pre- and main).

Final Event (October 25)

The concluding event on October 25 met our primary goal by encouraging discovery and interactivity around the collections. Daisy and Daniel established this date as the opening for their exhibition of player-created artifacts. Alongside the exhibition, players participated in a massive, multimedia, museum-wide scavenger hunt that involved six quests of varying difficulty. Each of the quests started with an artwork and was based around one of the six characters from the narrative: Daisy, Daniel, Blanche, McD, The Reverend, and WhatFor. Solving the quests put the spirits to rest and Daisy and Daniel were saved. Players had to send SMS messages, interact with actors, make sculptures out of foil, solve codes, find hidden objects, and even eat cake.

Fig 12: Using a sculpture to solve encrypted text

Fig 13: Cake inspired by an artwork

The quests were lengthy and complex, even the ones at the easy level, so I was very nervous that people would grow frustrated and tired and eventually give up. However on this point, I definitely underestimated the stamina, talent, and creative thinking of our participants! Altogether, 244 people played the game, with over 70 people completing all six quests to win a T-shirt.

Fig 14: A winning team

The fastest team took almost three hours to complete the quests, and the majority of players spent between three and five hours in the museum. Even those who did not finish everything usually completed three or four of the quests. We received extremely positive feedback from the players:

Our favorite part was actually early on in the experience when asked to form the piece of aluminum foil into a ghost. That sort of interactive project is always enjoyable, and hard to find in many large scale museums. […] Looking for the piece that fit the puzzle in a specific room (like "the tin man's daughter") was a fantastic way to examine the collections and pay specific attention to the various works of art on display. Overall this was a wonderful way to spend an afternoon, and we look forward to another such adventure. (Player: Paul Gerarden)

My favorite part of GOAC was the atmosphere of excitement that the game created. It was very much inspired by DaVinci Code, or something -- I loved the clandestine cell phone calls, the sign out the window, the codex -- all of those little touches added mystery and suspense. […] The game was SO much more than I expected. I thought that we'd come in for an hour or so and then get bored. Instead, we completed all six scavenger hunts. (Player: Miguel de Baca)

[I]t was a thoroughly enjoyable afternoon, and turned an already interesting museum into an exciting place of wonder, where every question led to another new discovery. (Player: Ben Buring)

Even though we were ‘exposed’ to the whole museum, I also liked that there were a couple of pieces of art that we actually had to sit and ponder. […] I never would have spent the time staring into [a] painting and trying to understand it if it weren't part of a task. (Player: Peter Everett)

I have spent quite some time in art museums and this is probably the first time that it felt like the museum was meant to be fun and interactive rather than more somber and pensive. It was really refreshing and definitely gave me a sense of community with the people who were coordinating the event and the other people participating in it. (Player: Jacquelyn Elder)

We realized that many of the on-line players would not be able to attend the final event. Once all the quests were completed and the spirits put to rest (and the cake eaten), we posted an epilogue to the Web site so that everyone could share the end of the story, whether on site or not. In addition, we wanted to involve the hardcore players in the event even if they couldn’t be there in person. We e-mailed a handful of players a request to create a code for the game, inspired by one of our nineteenth-century quilts.

Fig 15: Unidentified Artist, Flying Geese, about 1840, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Patricia Smith Melton

They rose to the challenge! Players created a new thread on Unfiction (http://forums.unfiction.com/forums/viewtopic.php?t=26918) and worked together to produce a code that used the triangles of the quilt as letters of the alphabet.

Fig 16: Flying Geese Code

On the other hand, many of the players on October 25 had not been following the game on-line. We anticipated this and designed the quests so that they would make sense to the uninitiated, while still creating a fulfilling experience for those who were familiar with the story.

Conclusion

Overall, the main game had two dimensions. One can be characterized by those parts of the game that actually asked people to do something physically: make the artifacts and participate in the live events. The other focused on following the mysteries within the narrative of the game, from the direct story posted on the game Web site to the content produced by in-game characters and museum staff. This two-layer approach was not something that we had planned, but it actually proved to be successful in that it attracted a wider variety of participants. Players could choose the aspects of the game that appealed to them, and still have a satisfying experience.

Ongoing Game (Recurring Module)

Immediately after the Main Game was complete, we started working on a module version. We took the most successful and popular aspects of the October 25 event and created a shorter version that could be played by groups in the museum in approximately ninety minutes. We wanted to offer this game on a regular basis, so we removed a lot of the elements that required staffing and replaced them with tasks that revolved around text messages and physical props. This version is no longer an ARG as it does not have the same sense of narrative or real-time happenings. However, it captures the spirit of the Ghosts of the Chance game and the concept of ARGs in general as it creates a layer of interactivity over a real world space, and challenges players to solve clues and puzzles in order to progress through the game.

The target audience is teenagers and young adults, though grown-ups have confessed to enjoying it also! As of January 2009, almost 200 players have participated in this version of the game. What is particularly gratifying for museum staff is that it has not yet needed any promotion. Word of mouth around the main game has led to all of our bookings so far.

Fig 17: Players participating in the Module Game

The ongoing game is not directly educational in that it is not tied to any specific curricula. Its purpose is to get people looking and thinking about art and art museums in a new way. We want to create a memorable experience that will make participants realize that art museums don’t have to be quiet, passive experiences; they can be interactive, social and FUN. The twenty-first-century audience has an increasingly short attention span, extremely high expectations when it comes to finding and engaging with information, the ability to communicate with friends and strangers quickly and on multiple platforms, and a very open approach to learning. The Ghosts of a Chance ongoing game meets the needs of this new visitor group, and opens up an important collection to people who might otherwise have left the building with a less than satisfying experience.

The feedback that we have received so far shows that the activity does offer value:

Our 10th graders were completely engaged in the program, and as you know we had to tear them away when our time was up. What was most exciting was their conversations afterwards, which were not only about the game, but about the art itself. Honestly, if someone had told me about a program which would leave 15-year olds discussing art with the same animation they show for sports and movie stars, I would not have believed them! (Rabbi Donald A. Weber)

“This museum was exhilarating and I never felt like sitting or sleeping. I wish someone had been filming us the whole time. Great experience!!”

“The scavenger hunt was amazing. It got everyone interested in the museum, even people who don’t like art.”

The scavenger hunt challenged the way I see museums. It synthesized fun, learning, and technology. The way they used phones was extremely innovative and different compared to other scavenger hunts. (10th Grade Players)

Guidelines and Recommendations

No two ARGs are alike, so it is difficult to establish set guidelines. However, I hope the following recommendations will be useful to those hoping to implement an ARG (or any type of interactive activity) in their institution.

- Don’t attempt to do a similar game to “Ghosts of a Chance”, or to follow the same model. The key to the success of our game was that it was new and unexpected. A second version along the same lines would not attract anywhere near as much attention from the players or the press.

- Definitely ensure upfront that you have full support from the decision-makers in your institution. Ghosts of a Chance would not have been possible without the support of our Director and Registrar, among others. Willingness to take risks is essential.

- Make sure that you understand what departments in your museum will be involved and that you have their support. I worked with staff in New Media, IT support, Public Affairs, Public Programs, Exhibits, and Registration in order to implement all the game-related content and events that were needed to support the story. I was careful to ensure that no-one was surprised by any requests that came their way, or by any public content issued by the museum.

- Be sure to dedicate significant time and resources to the management of the project. We wanted to allow the game designers to be as inventive as possible with the narrative, but there were certain museum standards and protocols that still had to be followed. Monitoring game development and coordinating with various museum departments definitely involved more time and attention than we had initially planned.

- Keep people informed! From the beginning, I established a contact list of anyone and everyone who was interested in the progression of the game and sent out regular updates. This included people within the museum as well as museum professionals across the country. By saving these updates, I also had the framework for my final report.

- Select an unusual name for your game. By googling “Ghosts of a Chance” I was able to immediately find on-line activity around it. Be aware, however, that the players may name your game for you! After the bodybuilder teaser in Boston, the hardcore players named our game “Luce’s Lover’s Eye,” although they did start to use Ghosts of a Chance after a few weeks.

- Don’t be tied to one physical location. A live event at your museum can be successful, but we did experience some mumblings from the players about the fact that all our live events were in D.C. Think of tasks that the players can engage in wherever they are in the world, and ask them to document and share their activities.

- Create a game with many possible levels of involvement. Players have different interests and available time, and don’t want to feel that they have to commit to everything by signing on.

- Don’t attempt to control or seed player activity on-line (definitely don’t try to initiate your game in Unfiction – they will find you out!), but do be open to interacting with players.

- Give the players something to do. Even if you know the story that you want to tell, be sure to include distinct tasks and/or activities to keep the audience engaged.

- Tour your institution with game designers. Even if you don’t create a large-scale event like Ghosts of a Chance, just seeing the artworks through a game designer’s eyes can be extremely revealing.

- Be a part of the game! The most interesting (and sometimes confusing) angle for me was the fact that I was a character in the game as well as the project manager. Involving museum staff in this way helps build support for your initiative and legitimizes the narrative.

And Finally…

Would the American Art Museum do another ARG? Definitely! It was incredibly fun – an interesting, challenging, and bizarre project to work on, and I enjoyed every minute. The museum received great press around the event, both during and after it, our collections reached a wider audience, and our staff and visitors saw the museum in a new light. The biggest challenge now will be taking it a step further. How can we design an experience that builds on the successes of Ghosts of a Chance, but still provides something fresh, innovative, and challenging for our audiences?

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge Michael Edson of the Smithsonian Institution, John Maccabee of CityMystery, the staff of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Anti-Boredom Playtime Society, the volunteers who assisted on October 25, and all of the players. I would also like to recognize the Luce Foundation endowment, which gives us the opportunity to implement such exciting and innovative projects.

References

McGonigal, J. (2008). Gaming the Future of Museums. http://www.slideshare.net/avantgame/gaming-the-future-of-museums-a-lecture-by-jane-mcgonigal-presentation. Consulted January 14, 2009.

Rose, B. (2007). Generation Y Plays Games on the Job. http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/businesstechnology/2003714122_geny20.html. Updated May 20, 2007. Consulted January 21, 2009.

Schroer, W. (2004). Generations X,Y, Z and the Others. http://www.socialmarketing.org/newsletter/features/generation1.htm. Updated April 16, 2004. Consulted January 21, 2009.

Simon, N. (2008). An ARG at the Smithsonian: Games, Collections, and Ghosts. http://museumtwo.blogspot.com/2008/09/arg-at-smithsonian-games-collections.html. Consulted January 14, 2009.

Szulborski, D. (2005) This is Not a Game. New Fiction Publishing.

Unfiction Discussion Forum. Last updated Jan 12, 2009. http://forums.unfiction.com/forums/ Consulted January 14, 2009.

Wikipedia article. Last updated Jan 12, 2009. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alternate_reality_game Consulted January 14, 2009.

Williams, D., N.Yee, S.Caplan (2008). Who plays, how much, and why? Debunking the stereotypical gamer profile. http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p254822_index.html. Consulted January 21, 2009.