Introduction and Background

“Researching Social Tagging and Folksonomy in Art Museums,” a National Leadership Grant for Research funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, was the collaborative effort of a consortium of U.S. art museums (and professionals that support them) known as Steve: The Art Museum Social Tagging Project. The research project sought to discover whether social tagging could enhance access to, and create engagement with, museum collections. One aspect of the research included the administration of a survey designed to elicit information about the tagging experience and to discover what may have motivated individuals to participate in contributing tags or descriptive terms for works of art. The data gathered from the survey has been useful in allowing the steve team to substantiate project hypotheses about the probable behavior and attitudes of the tag contributors, and to better understand the quantitative data about tags and taggers that has been gathered during the two-year research project.

Survey Development and Administration

A survey of people who tagged artworks during the research project was planned to complement the project’s overall experimental methodology, which is described in detail in “Tagging, Folksonomy and Art Museums; A report of the steve.museum research” (Trant, 2009). A survey – consisting of eleven multiple response and three open-end text questions – was developed to solicit information about contributors’ previous experience with tagging, their reasons for visiting the steve tagger, and their impressions of the tagging experience. The survey was delivered using Survey Monkey, a tool for creating Web-based survey instruments and capturing survey responses.

The survey was sent in February-March and August, 2008, to all tag contributors who had completed tagging activities, filled out the tagger registration form, and agreed to be contacted by the research team. Two distinct groups of participants were asked to respond: contributors who had participated in tagging in The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s community-specific installation (the “MMA” or “single-institution” tagger), and those who had contributed by tagging in the public site at http://tagger.steve.museum (the “public” or “multi-institution” tagger). The two separate tagging deployments were established in order to measure variations in tagging behavior and contribution between users with a relationship to a specific institution and those with a more general interest in tagging. Users from the two deployments were also segmented into groups based on the volume of their tagging activity. Each group was surveyed using separate data collectors in Survey Monkey, resulting in eleven separate data sets.

A total of 739 contributors were solicited; 238 surveys were completed. In the multi-institution installation, 361 users had agreed to be contacted. Of those, 32% had not submitted any tags and were extracted from the sample since they would not be able to provide adequate feedback about the experience of tagging. The survey link was sent by e-mail to the remaining 247. The group segmentation was derived using an equal distribution of tags in order to attain comparable amounts of data among groups. Users were sorted into groups based on the number of tags they had submitted. The single-institution survey had a larger pool of recipients (492) who also contributed more tags. User groups from this deployment had slightly different grouping thresholds based on the higher volume of tags submitted. The overall response rates for the multi-institution and single-institution surveys were 33% and 28% respectively. Users directly affiliated with the steve.museum project were excluded from the sample.

Survey Analysis

The survey instrument collected responses that allowed for investigation along a number of avenues. For purposes of this report, we have limited our analysis to questions directly related to key hypotheses of interest to the project partners. The analysis focuses on questions about motivation (reasons for tagging, and the effect of institutional affiliation); about the tagger’s perception of the tagging experience; and about the effect of work type or characteristics on tagging. Although identifying information provided by respondents might have allowed for the cross-tabulation of survey responses with contributors’ actual tagging behavior, we have not performed those cross-tabulations. Future work along these lines might prove valuable in relating the qualitative responses from the survey with quantitative data collected in the tagger. In addition, this survey analysis aggregates responses from contributors who tagged in any of the different research interfaces (Trant, 2009, section 8). Although we recognize that the particular interface presented to a contributor may have influenced his or her responses to some of the questions in the survey, the cross-tabulation required to determine which users tagged in which environments is beyond the scope of this particular study.

Some sample responses to questions were suggested in multiple choice options. Open-end text responses to these same questions were allowed in most cases. Many questions in the survey allowed the user to “check all that apply,” and the resulting tabulation of responses to these questions will therefore frequently total more than 100%.

Reasons to tag

The team hypothesized that users who feel a personal affiliation with a museum and its collection may be more motivated to tag than members of the public at large. Analysis of the quantitative data collected from the steve tagger deployments bears out this hypothesis. Users invited to tag by the MMA contributed four times more tags than those who were recruited in more generic, less personal, ways (Trant, 2009). The survey questions about motivation sought to validate the assumption about contributors’ interest in tagging on behalf of an institution with which they felt affiliated, but also looked for additional factors that might compel participation.

The expected experience

One survey question aimed to understand the expectations

of the visitor to the steve tagger: we were curious

about what the initial impetus for a visit to a museum tagging site might be.

Fig 1: Expectations for tagging: public and MMA contributors compared (check all that apply)

The vast majority of respondents were motivated by curiosity about tagging art (see Figure 1) with a slight difference in public participants’ (96%) level of curiosity compared with that of MMA participants (87%). Tag contributors in the public installation were also more interested in seeing tags that others assigned to works that they had also tagged: 48% of public tagger contributors cited “seeing others’ tags” as a motivating factor, compared to 29% of contributors in the MMA installation. Approximately one-third of MMA respondents (32%) wanted to be exposed to works other than those they had seen before, making this the second highest ranked motivation among MMA participants. There was very little interest (less than 10%) in searching for works similar to ones that had already been seen, and in seeing one’s previously applied tags. These responses indicate that tag contributors sought new experiences, exposure to new works of art, and were somewhat interested in seeing descriptions assigned by others to artworks.

Motivation for tagging

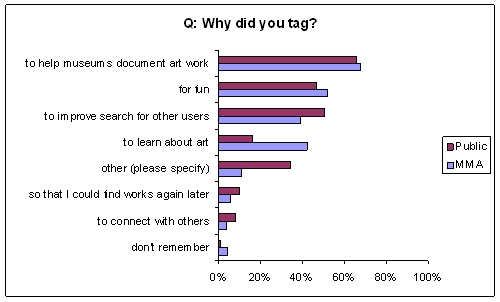

The survey also sought to understand some of the reasons that people might engage in tagging activities, especially in tagging works of art. The team hypothesized that many contributors are motivated by altruism, the desire to serve other individuals or institutions with which they are affiliated. A survey question, “Why did you tag?” included responses that supported the idea of helping others, as well as choices that included reasons for tagging usually seen in non-art environments such as del.icio.us or Flickr.

Helping museums to document works of art was the highest ranked response for both groups of contributors, at 66% amongst visitors to the public tagger and 68% for MMA contributors (see Figure 2). The second most prevalent reason for tagging in the MMA installation was “for fun,” at 52% (compared to 46% of public tagger respondents); the second highest ranked response in the public installation was “to improve search for other users,” at 51% (compared to 39% of MMA respondents). Tagging to learn more about art was a much stronger motivation for MMA respondents (42%) than for respondents to the public survey (16%). Amongst those surveyed, altruism does seem to be a critical motivating role, with the majority of respondents indicating that they tagged either to help museums with documentation or to enable search for other users.

Fig 2: Motivation for tagging: public and MMA contributors compared (check all that apply)

It is interesting to note that more than one-third of public tag contributors surveyed specified reasons for tagging other than those provided. Of these respondents, the majority indicated that they tagged for personal or professional research purposes. Some were conducting research on Web 2.0 applications in museums, trends in technology use, or folksonomies. A few of these participants were teachers who were interested in using the interface as a tool in their classes, and several others were students who tagged as part of a class exercise. A few respondents said that they tagged as a challenge to themselves, as a mind exercise. Recruiting strategies for the research project may have been partially responsible for producing these results, since significant recruitment took place within the community of museum and information science colleagues interested in the research project itself. In addition, solicitations to tag, as well as the tagging interface itself, all described the project as an investigation into the possibility of “enhancing access to museum collections,” and may have predisposed respondents to select the “improve search” option when queried about motivation.

Number of visits

The team hypothesized that tagging was an engaging activity that users would enjoy enough to do more than once. In the survey, respondents were asked to describe the frequency of their visits; we have cross-tabulated these responses against responses about contributors’ motivation for tagging, seeking evidence of links between satisfaction and engagement (more visits) and motivation. Survey respondents reported their visit frequency as follows: for the public installation: frequently 3, occasionally 65, and once 31, for a total of 99 respondents (see Figure 3); for the MMA installation: frequently 5, occasionally 60, once 73, and no response 1, for a total of 139 respondents (see Figure 4). The occasional user was in the majority in the public instance (66%), and the one-time visitor was in the majority in the MMA instance (53%). (Numerical definitions for “occasionally” and “frequently” were not provided in the survey and may cloud any detailed analysis comparing these two categories.) Some of the open-ended text comments received from MMA participants indicated that they might have been willing to do more tagging if they were asked via additional e-mail prompts. In addition, several MMA respondents indicated that they believed tagging was a one-time exercise, perhaps explaining the high number of those visiting only once. Fewer than 5% of users (public 3% and MMA 4%) said that they were frequent visitors; this indicates that users did not return to the tagging tool often, as was initially hoped.

Fig 3: Number of survey respondents from public tagger survey, by frequency of visits

Fig 4: Number of survey respondents from MMA tagger survey, by frequency of visits

The analysis shows that for both public and MMA installations, frequent tag contributors visited primarily for fun and were not interested in finding works again later or in connecting with others (see Figures 5, 6). Occasional and one-time participants visited for all reasons provided, but primarily to help museums document works of art. It must be noted that the research project’s experimental design deliberately limited the number and nature of interface variables: in particular, the kinds of variables thought by experts in social media to create “fun” environments – i.e. those that are most likely to create “stickiness” and return visits – were not offered to taggers in this phase of the steve project research. Far more research is required to understand the relationship between the number of visits by taggers and their perception of “fun.”

Fig 5: Motivation to tag / frequency of visits, public tagger (check all that apply)

Fig 6: Motivation to tag / frequency of visits, MMA tagger (check all that apply)

Institutional affiliation

One of the project team’s most important hypotheses surrounded the concept of institutional affiliation. The team’s conviction that a sense of association with a particular art museum (rather than with museums in general, or with the tagging activity) would induce participants to visit more, tag more, and possibly to provide more useful tags. The research experiment itself yielded strong affirming evidence for this hypothesis (Trant, 2009); one survey question sought explicit confirmation that a request from a local museum to help by tagging would influence a user to tag more.

Figure 7 charts the response to the question about whether respondents would be likely to tag more if asked by their local museum. Both sets of surveys indicated a strong positive response, with a slightly higher percentage of MMA respondents (75%) than public tagger contributors (69%) indicating that an institutional invitation would motivate them to tag more.

Fig 7: Willingness to tag if invited by local art museum

Perception of tagging experience

One survey question that was offered as a counterpoint to the “expectations” question charted in Figure 1 looked at what users felt about their tagging experience after the fact. In Figures 8 and 9, we have cross-tabulated responses about the user perception of the steve tagger experience against the user’s (self-defined) frequency of visits. Those respondents who found tagging interesting comprised the largest population of tag contributors in both installations (public 83% and MMA 70%). The public participants found tagging more fun (58%) than challenging (44%), while more MMA participants described their experiences as challenging (55%) than fun (47%). Frequent, occasional, and one-time participants visited for all reasons provided, except frequent visitors did not typically identify their experience as useless. It is not surprising to find that the vast majority of survey respondents responded positively to tagging and that those who had a negative reaction, finding tagging boring or useless, made up approximately 10% of those surveyed; this number would presumably be higher in a survey of all visitors to the steve tagger, not just those who completed the survey. Of those respondents who specified a response as “other,” a few from the public tagger wanted more control over their experience, and others indicated that the subjective nature of the experience made tagging difficult. Those who specified a response of “other” in the MMA survey pool said that the exercise was time-consuming and confusing. A few also questioned its usefulness. One respondent indicated that, as structured, the tagging activity might pass a threshold for continued engagement: “It was fun and interesting for a while, but it became boring.”

Fig 8: Perception of tagging / frequency of visits, public tagger (check all that apply)

Fig 9: Perception of tagging /frequency of visits, MMA tagger (check all that apply)

The effect of object characteristics

Object type

The team was interested in knowing whether the characteristics of an object (its type, origin, or dates) affect tagging behavior. Several survey questions were posed to assess the tag contributor experience related to the characteristics of the works tagged and to provide a comparison with the quantitative analysis. We hypothesized that two-dimensional works (i.e. paintings, photographs, and prints and drawings), which tend to contain more representational content and might require less technical knowledge to describe, would be easier for the non-specialist user to tag. We asked the questions: “Were certain types of art easier to tag?” and “If so, which?” Responses suggest that two-dimensional works were considered easiest to tag (see Figure 10), although approximately one-quarter of respondents in both installations (public 26% and MMA 22%) said that they did not remember if some works were easier to tag than others. This could be due to the fact that some time had passed since the respondents actually tagged or that there was not a noticeable difference to some contributors; others may simply have skipped works that they were not compelled or able to tag. In fact, several users noted that they had tagged only paintings. Three-dimensional works were obviously thought by the majority to be more difficult to tag, while textiles (rugs, clothing, etc.) ranked as least easy to describe (public 4% and MMA 9%). Respondents were also given the option to specify their response as “other” (public 14% and MMA 7%). Respondents stated that, “representational works had more obvious content hooks” and that “paintings, photographs, prints and drawings are always easier to tag as most would base their tagging on the subject/image. The three dimensional is different: most of the "tags" are already included in the description/label provided by the museum.”

Fig 10: “Easy to tag” by Object Type (check all that apply)

Object culture

The team also hypothesized users would find it easier to tag works from their own culture; that is, they might struggle with non-Western or ancient works, preferring works created by Western artists and in the modern era. When asked if works from a specific period or geographic location were easier to tag, respondents felt most strongly that European and American art was easier to tag (public 36% and MMA 45%: see Figure 11), although almost one-third of respondents stated that they did not remember if some works were easier to tag than others. As with a similar question asked about two-dimensional and three-dimensional works, this might be because contributors had simply skipped works that were difficult to tag, or because the object culture types suggested in the survey were unfamiliar. In some, but not all, interfaces, taggers were provided with museum-created caption information that would have identified the work by culture, although we cannot be certain that at all times users knew what they were looking at. MMA tag contributors found Medieval and Renaissance works easier to tag (27%), compared to public contributors at 19%; contributors from the public survey were slightly more comfortable tagging modern and contemporary works (25% versus 21% for MMA). Both sets of respondents were least comfortable tagging Asian, African, or other non-Western works (public 11% and MMA 8%), providing support for the core hypothesis about the influence of culture on ease of tagging.

Fig 11: “Easy to tag” by Culture or Period (check all that apply)

A few factors to note: we were unable to make any firm determinations about whether objects were from the survey respondent’s culture, since we did not collect demographic information for survey respondents. It is, however, assumed that the large majority of respondents and taggers were North American, as recruiting activities focused on communities in the U.S. and Canada. Certain users might have had a richer understanding of the collection that they were tagging. A few of the open-ended text responses also support the team’s assumptions: “ease of tagging just depended on whether the piece (or some aspect of it) was in some way familiar to me.”

Conclusions

The survey of tag contributors affirms some of the key findings of the data analysis, and provides preliminary insights into the motivations and experience of those who tag art. Users in this study expressed altruistic motives for their tagging activities, indicating that they tagged in order to assist museums in documenting works of art and, to a lesser extent, to aid individuals who may be searching for artworks. People wanted to be involved with the work of museums and to respond to their requests for input. This may provide museums with a justification for making appeals both to individuals who are already affiliated with their institutions as well as to those from the general public. Some valuable information about the experience of users in tagging objects with different characteristics was also collected, and should be verified in further studies of object characteristics and the relationship to tags and contributor behavior.

Survey respondents’ motivations for tagging must be seen through the limited prism of their tagging experience in the steve project’s experimental interface(s). Although survey respondents indicated that they tagged for fun, and to learn about art, the project’s overall experimental construction constrained the conclusions that could be drawn from the data and the surveys. The project team made a deliberate choice to conduct the testing using a set of simple interfaces with minor variations on the presentation of objects or object-related information. Data collected in these simple tagging environments provides important baseline information about the behavior of those who tag art and allows useful conclusions to be drawn about the effect of object choice and metadata presentation on tag generation. These interfaces, however, contained few elements designed to engage, reward, and inspire, and an examination of how best to create long-term engagement with taggers - how to make tagging applications “sticky” – awaits testing in environments that are designed to provide “fun” experiences or learning environments. Such environments might contain social media elements (user profiles and user-created communities); elements of competition and reward; or the possibility to customize or personalize the tagging experience.

Review of open-ended text responses supplies some of the most compelling and lively information about users and their experiences, providing perspective on what drew individuals to tagging artworks. The vast majority of respondents had a positive reaction to the project, and comments collected in the surveys included the following statements:

I love, love, love this. I feel like I am in school again learning and contributing to this. It has become a hobby, I try to do some whenever I have a quiet moment. I look forward to doing it. I am so excited to be a part of it.

Very interesting project, I found it when researching about taxonomy, folksonomy, Web semantics and museum. We are working to implement the Steve software at our project.

Loved the experience. Immediately told all my museum goer & "art" friends – they seemed to like it too.

1. It's fun, interesting, educational, a "trip". 2. Makes me feel I have a stake in the collections. 3. Delightfully self-aggrandizing.

Should happen at more museums. Very interactive.

This was a fantastic project! I would have LOVED to have been on the editorial team that had to go through and edit the tags. Thanks for doing this – I think it will make the artwork so much easier to search for for users, particularly students and non-experts.

Ultimately, research into the potential of tagging as a tool for museum practice cannot be considered complete until a thorough study is undertaken of the various methods that might be employed to create long-term engagement between tag contributors and museum collections. In the meantime, these visitor voices encourage the project’s members to think about ways to continue to offer tagging experiences that motivate and teach.

References

Trant, J. (2009). Tagging, Folksonomy and Art Museums: Results of steve.museum’s research. Available: http://conference.archimuse.com/files/trantSteveResearchReport2008.pdf