1. Community-Generated Content in the Museum

Motivating the creation of visitor-generated content in museums and galleries is a new tendency. In the context of museums, User-Generated content (UGC) has also been referred to as visitor authored content (Simon, 2007), visitor response (McLean & Pollock, 2007) and visitor contributed content (Fisher et al., 2008). Wakkary has highlighted the importance of including the voice of scientists working in the museum because their localized knowledge offers another view of the artifacts displayed (Wakkary, 2005). Kevin Walker has also observed the benefit of a system that links “curatorial and user-generated content” (Walker, 2008, pp 114). As design-researchers working outside the museum context, we have witnessed this transition towards UGC, specifically the role that new media and exhibition designers have in motivating collaborations within the museum community that lead to this sort of production.

We propose to use the term “community-generated content” instead, because it is the way to break open the visitors/staff dichotomy. Community-generated content is used here to refer to content produced by visitors, staff (including guards, guides, curators, educators, marketing specialists, cleaning personnel, volunteers), as well as external researchers, artists or designers.

In a previous project, we used an on-line map as an interface where comments about the works in an exhibition could be gathered, and this proved successful. Visitors could identify the artwork that they wished to comment on and place their comment on the map (Salgado & Díaz-Kommonen, 2006). In this paper, we analyze two additional case studies where the museum community was able to annotate and comment using on-line maps. The first case involved the use of the Urban Mediator (UM) software in the context of an exhibition at Kiasma, the museum of contemporary art in Helsinki. Urban Mediator offers the possibility to put comments on a city map, in this case the map of Helsinki. The second case entailed the use of the ImaNote software at the Design Museum in Helsinki. Through ImaNote, it is possible to comment on a compiled image made out of the objects planned to be in the exhibition.

Fig 1: Urban Mediator Helsinki and The Secret Life of Objects

2. Presentation of the Case Studies

The two case studies were developed at Media Lab Helsinki in cooperation with the two museums. Both bring into play the use of Open Source software. Both softwares, Urban Mediator (http://mlab.taik.fi/urbanmediator/) and ImaNote (http://taik.fi/imanote/), enable users to leave comments in text or audio-visual format related to the themes or the artifacts in the exhibition. These comments are visualized through the map components of the systems.

The work was led by two different teams, each with a different research agenda. The proposed strategies for collaboration between design-researchers from Media Lab and the museum staff were also different in each case. Whereas ImaNote was designed with the museum context in mind, UM was not, and hence its use here was more experimental. Moreover, the time and commitment to the project varied in each case. The ImaNote project at the Design Museum lasted for several months (from October 2007 to June 2008) and demanded more time and dedication than the Urban Mediator project at Kiasma (see Table 1).

Regardless of the differences in agendas and strategies, we chose to approach these two cases jointly in this paper precisely because of the important concerns they bring out with regard to designing digitally mediated participation in museums.

Urban Mediatorth(UM) at Kiasma |

ImaNote at Design Museum |

|

|---|---|---|

Name of the exhibition |

Fluid Street – Alone, Together |

The Secret Life of Objects, An Interactive Map of Finnish Design |

Exhibition description |

The exhibition featured works of art related to streets and their different roles. Along with the exhibition, a series of performances, events and interventions at the Museum and in the surrounding urban areas was planned, as was a series of themed walking tours in the city. |

A selection of objects from the Museum’s collections dating from 1874 to 2008. Along with the exhibition, a series of workshops related to it were held. |

Exhibition time |

5/9 – 9/21, 2008 |

3/18 – 6/1, 2008 |

Time on-site |

5/9– ? (exact date unknown) |

The stand was at the exhibition space during the entire exhibition period. |

Time online |

The map was on-line during the time of the exhibition and is still available at http://um.uiah.fi/hel (Kiasma topics) |

The map was on-line during the entire exhibition period |

Focus of the comments |

Traces of nature, graffiti and art in the city streets |

Objects in the exhibition |

Table 1: Comparison of ImaNote and Urban Mediator

2.1 Urban Mediator in Kiasma

Urban Mediator was developed by the Arki research group as one of the activities carried out by the EU-funded ICING research project (Innovative Cities for the Next Generation, 2006-2008). Urban Mediator is a server-based software that provides a way for communities to mediate local location-based discussions, activities, and information. Urban Mediator uses a map-portrayal service as a means to represent location-based information and complements that information with a set of tools designed to allow users to process, share and organize it. Urban Mediator functions can also be embedded in Web sites using various Urban Mediator Web widgets. Since June 2008, UM has been available as an Open Source software package. Several Urban Mediators have been set up and are available on-line for public use, including UM Helsinki (http://um.uiah.fi/hel), which was used in the Kiasma case.

In developing UM, the goal was to experiment with solutions that would permit city administrations and citizens to share location-based information. The efforts were therefore focused on possibilities for city-citizen information sharing, and many of the study cases dealt with participatory projects defined in collaboration with planners from city administrations in Helsinki (Saad-Sulonen & Suzi, 2007; Botero & Saad-Sulonen, 2008; Saad-Sulonen & Botero, 2008).

The UM was in use in Spring 2008 in various projects engaging the general public (Saad-Sulonen & Botero, 2008). The Kiasma staff learned about UM and decided to see whether it could be used as a tool for public intervention in the upcoming exhibition Fluid Street. Along with the art exhibited at the Museum, they were going to organize a series of walks in the city, inviting the public to take part in documenting various aspects of the city, such as art and artistic expression in the streets, and nature in the city. These walks were to be led by artists or experts, and the idea was for participants to document (with digital photos) or take notes and then place these on the map of Helsinki, available via UM, on a computer set up for that purpose in Kiasma. Moreover, anyone could also use UM on-line. For the UM designers, this case was interesting as it made it possible to test UM in a different context from urban planning, this time in the context of public participation in museums.

In order to introduce the Urban Mediator software as a tool for this project, a co-design session was organized for the designers and some of the museum staff. Paper and pen prototypes of the software were used for exploring the key features and the customizable elements. Since the Kiasma Web master was at that session, it was easy to decide how the Urban Mediator Web widgets would be included on the Kiasma Web site, enabling the site’s visitors to interact directly with the Urban Mediator topic created for the exhibition. Except for two short meetings and e-mail exchanges, after that initial session there was not much more collaboration between Mlab and Kiasma teams.

This project did not elicit many contributions from museum visitors, tour participants or Web site visitors. The main reason might have been the lack of active collaborations in designing ways for inviting people to contribute. The reasons for this limited success will be further discussed in the following sections.

2.2 ImaNote in the Design Museum

The System of Representation Research Group (http://sysrep.uiah.fi) has been working on the development of ImaNote, an image map notebook annotation tool (http://imanote.uiah.fi). As a type of social software, ImaNote is a Web-based multi-user tool that allows users to display a high-resolution image or a collection of images on-line and add annotations and links to those images. It is possible to make annotations related to a certain point or area in the image. Using RSS (Really Simple Syndication), users can keep track of the annotations added to the image or make links to share the image with others. ImaNote is an Open Source and Free Software released under the GNU General Public Licence (GPL). It is a Zope product, written in Python. Zope (http://www.zope.org) and ImaNote run on almost all operating systems.

ImaNote was initially created to share cultural heritage content connected to two cartographic specimens: Carta Marina, and Map of Mexico 1550. Its development was a collaborative effort involving the Systems of Representation and the Learning Environments research groups of the Media Lab at the University of Art and Design, Helsinki.

“The Secret Life of Objects” was the name of the project in which ImaNote was used in the Design Museum to gather user-generated content. In 2005, the first trial in which ImaNote was implemented according to the same logic took place in Kunsthall, Helsinki (Salgado & Díaz-Kommonen, 2006).

In the context of this project, the Design Museum in Helsinki offered two events and four workshops to the public. Additionally, through one seminar and several meetings the Museum staff and the Media Lab team framed and developed the project. Initially, the interactive map was presented and tested at a stand in the exhibition of the Museum’s permanent collection, which has been housed in the basement showroom for the past six years.

The material collected during these initial experiments served as the basis for engaging the Museum’s staff. The initiative to develop an exhibition in which an interactive map of comments played a principal role came from the staff. Indeed, the new exhibition took part of its name from our project: “The Secret Life of Objects, an Interactive Map of Finnish Design.”

A stand displaying the map was part of the exhibition that featured the Museum’s permanent collection (now out of the basement) held from March 18th to June 1st, 2008. For the opening, the map was furnished with prepared materials (videos, pictures, music, poems, historical information, etc.) collected at workshops and over the course of the weekend when a prototype was tested. Co-designing this exhibition and the prior workshops with the Museum’s education team provided a means to develop this prepared material and, thus, to influence the digital comments left by casual visitors (Salgado et al., 2008). Nobody encouraged visitors’ participation during the exhibition, and the exhibition itself was not supervised. Nonetheless, around one hundred comments were collected through the stand. Most of these comments were printed during the course of the exhibition and displayed near the objects they discussed.

Staff members, including guards and guides, left comments on the map and used it as part of the exhibition’s guided tours. As way to enrich the discussion, we also tried to include comments by external designers whose pieces were on exhibition in the Design Museum even when these designers were not part of the Museum’s staff.

ImaNote at Design Museum |

Urban mediator

at Kiasma |

||

|---|---|---|---|

User research |

Explorations |

A prototype was tested in the permanent exhibition during one weekend and two events at the Museum. 15 days of observation at the Museum during the course of the exhibition itself. |

No user research done in the context of Museum |

Workshops and seminar |

3 workshops and one seminar held in collaboration with the Museum staff at which we collected material for the map |

One co-design workshop with the Museum staff |

|

Interviews |

27 interviews with visitors and Museum staff |

No interviews |

|

Collaborations |

Team in Mlab |

1 student + 2 researchers + technical support and expert advisor |

1 researcher + 1 software developer + 1 interface designer + 1 student assistant |

Team at the Museum |

1 lecturer + 2 workshops guides |

1 head of education and 1 museum lecturer (both from the Museum’s education department) + 1 webmaster (+ 3 tour guides) |

|

Table 2: Comparison, part 2.

3. Mapping Multiple Design Options: Formats, Devices and Artistic Expressions

The content in these pieces are both the maps and the added digital comments. We use the term “digital comments” to refer to the audiovisual or textual material left on the map created in relation to the exhibition’s materials before, during or after the visit. These comments deal with different museum practices and are displayed via an array of devices; in some cases, they themselves constitute creative expressions.

In some cases visitors were invited to contribute their personal objects. Examples of other projects that have used similar techniques are People’s Show (2003) (http://www.victoriagal.org.uk/ index.cfm? UUID=2C53FAD3-9C8D-44AC-A3C13A18423CB49B) and World Beach Project (on-going) (http://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/textiles/lawty/ world_beach/map_gallery/index.php) at The Victoria and Albert Museum, England; Live your life at Helina Rautavaara Museum (2008) (http://www.helinamuseo.fi/#), the People’s Portrait Project in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada (McIntyre, et al.,2008).

Digital comments as part of an exhibition experience take the form of audio (Ferris et al., 2004; Samis, 2008), video (Bernstein, 2008), text (Von Appen et al., 2006; Fushimi, 2006; Salgado et al., 2008), voting systems (McLean & Pollock, 2007), and photographs with audio (Fisher et al., 2008; Walker, 2008). Visitors could access/leave these comments on the gallery through stands, PDAs, iPods, mobile phones or embedded technology.

In the cases we describe in this paper, visitors could leave and access the comments from a stand at the exhibition or on-line. In the project at the Design Museum, text comments left on the map by the Museum community were printed and displayed throughout the exhibition. Visitors were allowed to leave open comments related to the exhibitions in question, and there were no limitations regarding the length of comments. We propose that there is a qualitative difference between this type of comment and other text-based interventions such as tagging and voting.

Visitor-created content can have a creative quality. For example, in The Art of Storytelling exhibition at the Delaware Art Museum, visitors personally engaged the artworks through their own narratives (Fisher et al., 2008). Creative comments involving emotion, poetry, memory and bodily sensations were also collected in relation to the exhibition Take Your Time: Olafur Eliasson, at SFMOMA (Samis, 2008). In the case of our project at the Design Museum, visitors created not only comments in the form of text (poetry, opinion, short story) but also improvisational music based on the objects in the exhibition. Our strategy geared towards eventual visitors was to use comments that had been previously created at the workshops. Such comments included improvisational music and poetry, and they served to trigger new digital comments from visitors (Salgado et al., 2008).

4. Navigating Community-Generated Content

The use of on-line maps for gathering and displaying rich media information is a concrete possibility in the context of museums; these maps offer a means to display both visitor and staff comments non-linearly. This non-linear navigation allows multiple access points for browsing the content and, thus, enhances the interplay between parallel dialogues and perspectives related to the exhibition content. Both Urban Mediator and ImaNote permit this type of navigation.

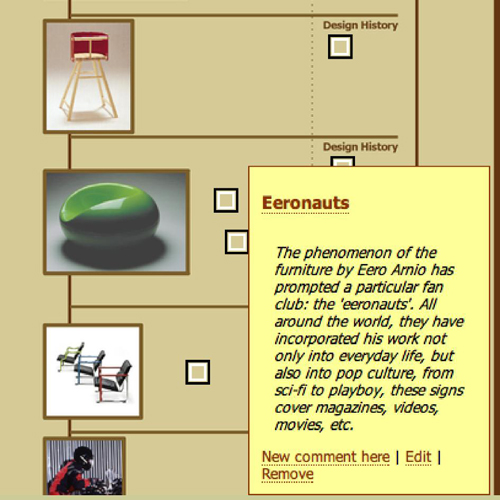

At the Design Museum the objects were points for discussion; visitors placed their comments and, with them, a rectangle or square on the map. Thus, the conversation had many threads, all based on the objects exhibited. At Kiasma, participants in the walking tours or on-line visitors needed to create the object under discussion, for example by taking a picture or commenting on a location. The participants had two themes to choose from, ‘nature traces’ and ‘art and graffiti,’ which were also the themes of the two series of walks.

The non-linearity of the discussion - as opposed, for example, to a Web log, where comments appear chronologically one after the other - allows for random exploration without clear hierarchies, and this was just what we wanted. In keeping with the multiplicity of voices and art/design works exhibited, this tool allowed us to open several discussion threads at the same time. In our opinion, the map as interface provides a democratic forum for displaying community-generated content. Museum staff and visitors’ comments were displayed in parallel. Nevertheless, in the case of the Design Museum, we formulated a distinction between comments by creating an image with several places to locate comments. This made it possible to identify, for example, comments made by the staff about the design history of the objects displayed and comments collected during workshops.

Fig 2: Screen for Eernauts comments

Comments generated over the course of the exhibit opened up the delicate question of ownership. Who preserves and has the right to use the digital comments collected during the exhibition? In these particular cases, the comments are housed at the Media Lab servers, and the museum has not made any attempt to get a copy, or to save them as digital documentation. Should this be interpreted as a lack of interest in community-generated content related to the exhibition?

At our stand at the Design Museum, we put up a sign stating that the exhibition was part of a research project and the material gathered was going to be used towards that research. Nobody contacted us to ask for further details about this, though. We asked for special permission when publishing pictures of participants in the workshops. Generally, though, it seems that people are eager to contribute their opinions and feelings and are not overly concerned with how their contribution will later be used.

Many members of the museum staff left personal comments on the interactive map, but - with the exception of one guide - they did not identify themselves. Although most of the comments were personal stories, they were not signed by their authors. This seems to suggest that, in this context, authorship is not a relevant issue. In the future, if participatory practices such as those described here are implemented in every exhibition and the number of contribution increases, the issue of authorship could become important to the community.

In the case of Kiasma, the Museum staff and designer provided the first pictures and comments as a way to populate the themed topics on Urban Mediator. Some of the Museum staff used their full names, others only their initials. However, the initial number of contributions was not large, and no one took the role of “owner” or “guardian” of the collections of information; therefore, there was no one actively encouraging others to contribute.

Furthermore, the experts who guided the walks were not deeply involved with this project either. They were quickly shown how to use the software, but they did not end up providing material to populate the UM topics related to the walks they were leading.

5. “Don’t Leave Me Alone!” Said the Software

While in this article we concentrate on the possibilities offered by these two annotations tools for displaying community-generated content, we also believe that in the museum context a key issue is not only how to design friendly software, but also how to integrate it into the exhibition design, the Website, and the museum’s practices. Only by conceiving these elements as part of a single ecology is it possible to effect design geared towards the holistic visit experience.

One of the topics we highlight is the need for dialogue between the on-site and on-line components of the exhibition. The on-site experience; that is, the experience within the physical context of the museum, can introduce museum visitors to the on-line extension of an exhibition. As well, the on-line experience can attract on-line visitors to the galleries.

5.1 Integration with exhibition design

In user studies conducted at the Design Museum, we realized that the stand was mainly understood as a point of information. Its participative and innovative characteristics went largely unnoticed because desktop configurations are widely used at information points in museums. Therefore, we printed an oversize sign clearly stating the use of the stand: “Interactive map. Find videos, music, opinions. Leave your comment.” Although this led to a certain increase in participation, it is clear that in order to better communicate the participative characteristics of the stand, the design needs to emphasize its participative qualities.

Other communication materials at the exhibition were flyers, a letter, a booklet, visitors’ comments, and a sign with the credits for the exhibition participants. Flyers gave the visitors information about the project, the URL of the Web log, and a reminder to visit the map on-line after the visit. Signed by the objects, the letter asked visitors to leave stories, memories and opinions that connected them with the objects in the exhibition. The staff wrote the booklet explaining the objects at the exhibition. Visitors’ comments were printed and placed throughout the Museum, near the exhibited objects. Nonetheless, the small number of comments left during the first month of the exhibition made it clear that the exhibition concept was not properly perceived. When we printed most of the comments collected, their presence was perceived and, in many cases, appreciated.

Integration with the exhibition design was less successful at Kiasma. The exhibition, the walk tours and the on-line interaction possibilities had not been sufficiently interwoven. The exhibition was big (it included all the Museum premise’s floors). The tours were simply an extra activity offered by the Museum for those interested in participating, and the on-line map was seen as an extension of the tours. The initial idea of the head of the Museum’s education department was that, after each tour, the participants would add their impressions or documentations to the on-line map. The museum had also placed a big paper map on a wall where people could place sticky notes with comments. There was no clear connection between the paper map and the on-line map; indeed, the map of the city shown in each was different (the on-line map was the official map from the City of Helsinki; the one on the wall a stylized version of another map). Both the big paper map and the computer stand were in the same space, but there was no visual connection between them or any written explanation indicating that they served a common purpose. It was easier for visitors and tour participants to write comments on the sticky notes and paste them on the wall map than to use the on-line map. Nonetheless, many of the messages written on the sticky notes had no relation whatsoever with the theme of the exhibition or the mapping exercise. Moreover, the setting of the computer stand was not inviting, and there were no explanatory texts or diagrams next to it except a sign saying, “Report your observations from the walk tours – http://um.uiah.fi/hel (Urban Mediator Helsinki)”.

5.2 Integration with the museum Web site

Though some members of the staff could add minor changes, the Design Museum outsources its Web site design. During the time of the exhibition, it was possible to access the interactive map through a link from their homepage.

The visibility of the link was an issue since an on-line visitor would need to scroll the page to get to it. Although we cannot prove it, we believe that most of the visitors trying to reach the map were first visitors to the exhibition. We believe that better integration with the Web site, not just in terms of the link, would have enhanced the collaboration between on-line and on-site resources.

One of the main features of Urban Mediator is the possibility to create Web widgets that can be embedded into any Web site, making it possible for users to use the tool’s functions directly from the Web site. As Kiasma has only one Web master to edit its Web site and to embed the widgets as needed, and because this person was on sick leave at that time, the Web pages were never finished. Some required widgets were left missing from the Kiasma pages, and others were not placed on the site in a clear fashion. It was therefore difficult to understand how the widgets should be used. Moreover, instructions had not been added to pages. Finally, because the pages were not ready, they could not be shown on the computer located in Kiasma. The page showing on the computer screen was, therefore, the homepage of UM Helsinki, making it more difficult for the visitors to understand what to do (this main page displays other topics concerning UM Helsinki, like a traffic safety public participation project). While the widget idea has been successfully tested in other cases (Botero & Saad-Sulonen, 2008; Saad-Sulonen & Botero, 2008), it requires the full collaboration of those responsible for a museum Web site.

5.3 Integration with museum’s practices

With the software used in these projects, it is possible to add links to external resources and to browse for images to add to a comment. We encouraged visitors to leave comments in an array of formats, not only text but also audiovisual data.

In the case of the Design Museum, we used the audiovisual material created as part of the project to encourage creative audiovisual comments. Since the Museum guides collaborated so fully with the project, they explained the possibilities for contributions on-line and on-site in their guided tours. These guides were part of our project from the very beginning; they conducted workshops at the Museum and added comments to the map, encouraging visitors to do the same. Since working at a small museum often entails performing multiple tasks, the guides also worked at the Museum’s information desk and as guards. Guides communicated the possibilities of the participative piece to teachers who came with their students, for example, or to casual visitors to the museum. This type of collaboration with different members of the staff is crucial to external researchers who often have little direct contact with everyday visitors.

In the case of Kiasma, the designers made little effort to involve the ‘ground staff’ such as guides and guards. This could have been important because they are the ones that can, during their rounds, pass by the space where the computer is located and offer assistance. Moreover, the collaboration between the designers and the experts invited to lead the walks in the city was not fully developed. There was no clear strategy decided on how participants in the walks should be guided to contribute to the UM map, even though the walks did end in the space where the computer was situated. As a result, participants in the walks were not active in providing what should have constituted the base material on UM, which in turn, might have triggered more interest from Web site visitors and prompted them to contribute.

We believe that integrating community-generated content projects with other museum practices such as publications and marketing campaigns would also benefit participation.

Conclusions

It is not enough to present a tool and place it in the museum space. Particularly in the case of Kiasma, the shortcomings of the use of UM point to the need for a holistic approach to designing participation in museums.

Our strategies/recommendations for engaging the museum community in commenting on exhibitions and using on-line maps stress the need for:

- Integration of resources and practices: pooling digital and analog methods

- Time and dedication for including museum staff members and external contributors

- Special invitations for groups of key contributors

- Prepared materials for triggering creative digital comments

On the basis of these experiences, we suggest the need to closely examine the strategies used to motivate participation on the part of visitors, staff and external collaborators. Adequate strategies are key to making these projects into real participative experiences. In this paper, we have discussed lessons learned from both unsuccessful approaches and more successful ones. Long-term collaboration could benefit the mutual understanding of all the actors involved in the museum ecology: visitors, external researchers and museum staff. Finally, we highlight the need to plan a coherent network of participatory activities, one that integrates on-line tools into the holistic museum experience.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all the people that have made these projects possible and enjoyable: Svinhufvud, L., Botero, A., Krafft, M., Kapanen, H., DeSousa, D., Eerola, E., Louhelainen, A., Vakkari, S., Vilhunen, M., Kivilinna, H., Jauhiainen T., Timonen, A., Luhtala, M., Kaitavuori, K., Suzi, R., van der Putten, M., Singh, A., Matala, P. and Hyvärinen, J.

References

Bernstein, S.(2008). Where Do We Go From Here? Continuing with Web 2.0 at the Brooklyn Museum. In D. Bearman & J. Trant and (Eds.). Museums and the Web 2008: Proceedings (CD-ROM), Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2008. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2008/papers/bernstein/bernstein.html. Consulted 10.01.09.

Botero A. and J. Saad-Sulonen (2008). “Co-designing for new city-citizen interaction possibilities: weaving prototypes and interventions in the design and development of Urban Mediator”. In Proceedings of the 10th Participatory Design Conference. University of Indiana Bloomington.USA.

Ferris, K., L. Bannon, L. Ciolfi, P. Gallagher, T. Hall, & M. Lennon (2004). “Shaping Experiences in the Hunt Museum: A Design Case Study”. In Proc. of DIS2004, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Fisher, M., B. Twiss-Garrity & A. Sastre (2008). The Art of Storytelling: enriching art museum exhibits and education through visitor narratives. In D. Bearman & J. Trant & (Eds.) Museums and the Web 2008: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Consulted on 16.06.08 from the World Wide Web: http://www.archimuse.com/mw2008/papers/fisher/fisher.html

Fushimi, K., N. Kikuchi and M. Kiyofumi (2006). An Artwork Communication System Using Mobile Phones. In D. Bearman & J. Trant (Eds.) Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Consulted on 16.06.08 from the World Wide Web: http://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/fushimi/fushimi.html

McIntyre, G., et al. (2008). Getting "In Your Face": Strategies for Encouraging Creativity, Engagement and Investment When the Museum is Offline. In D. Bearman & J. Trant & (Eds.) Museums and the Web 2008: Proceedings. (CD-ROM), Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2008. Consulted on 16.06.08 from the World Wide http://www.archimuse.com/mw2008/papers/mcintyre/mcintyre.html

McLean, K. and W. Pollock (2007). “Crafting the Call”. In K. McLean & W. Pollock (eds.) Visitor Voices in Museum Exhibitions. Washington DC: Association of Science and Technology Centers, 14-19.

Saad-Sulonen J. and A. Botero (2008). Setting up a public participation project using the Urban Mediator tool: a case of collaboration between designers and city planners. In Proceedings of NordiCHI 2008: Using Bridges, 18-22 October, Lund, Sweden.

Saad-Sulonen, J. and R. Susi (2007). Designing Urban Mediator. In Proceedings of the Cost 298 conference: participation in the broadband society. May 2007, Moscow, Russian Federation.

Salgado M. and L. Diaz-Kommonen (2006). Visitors’ Voices. In D. Bearman & J. Trant & (Eds.) Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings. (CD-ROM),Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2006 a. Consulted on 16.06.08 from the World Wide at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/salgado/salgado.html

Salgado, M., J.Savolainen, L. Svinhufvud, A. Botero, M. Krafft, H. Kapanen, D. DeSousa, E. Eerola, A. Louhelainen and S. Vakkari (2008). Co-designing Participatory Practices around a Design Museum Exhibition. In the Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of Design HIsotry and Design Studies. Another Name for Design, Words of Creation. ICDHS 2008, Osaka, Japan, 106-109.

Simon, N. (2007). “Discourse in the Blogosphere. What Museums Can Learn from Web 2.0”. In Museums and Social Issues, volume 2, Number 2, Fall 2007, Left Coast Press, USA, 257-274.

Tallon, L. and Walker K. (2008) Structuring Visitor Participation. In L. Tallon & Walker K. (Ed.) Digital Technologies and the Museum Experience. Handheld Guides and other Media. Altamira Press, Plymouth, UK,109-124

Von Appen K., Kennedy B. and Spadaccini J., Community Sites & Emerging Sociable Technologies, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2006: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2006 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/vonappen/ vonappen.html editor's note. URL corrected Jan. 21, 2007. Consulted on 25.01.09

Wakkary, R. and Evernden, D. (2005) Museums as Ecology: A Case Study Analysis of an Ambient Intelligent Museum Guide. In D. Bearman & J. Trant & (Eds.) Museums and the Web 2005: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 31st, 2005. Consulted on 16.06.08. http://archimuse.com/mw2005/papers/wakkary/wakkary.html