Introduction

Parks Canada, an agency of the Canadian federal government, is responsible for protecting, managing and interpreting Canada’s nationally significant natural and cultural places. The Parks Canada network is vast. It spreads throughout Canada, and includes all 42 of Canada’s national parks, 158 of this country’s national historic sites, and 3 national marine conservation areas. Local site staff and field unit staff manage each park and site, and are supported by regional service centres and the national office in Gatineau.

Although Parks Canada is well-regarded in the minds of many Canadians, the agency is facing a number of challenges. Overall, sites have seen a significant decline in attendance in the past 5 years, with national historic sites suffering the largest losses. This decline has been partially attributed to a changing Canadian population and diminishing relevance to this audience. Perhaps, it has been suggested, as Canadians become more urban and live further from national parks and historic sites and as the traditional audience ages and shrinks in number, Parks Canada’s sites are no longer meeting the needs of Canadians.

To deal with this challenge, Parks Canada is striving to reach new audiences through a renewal of its offerings at sites and parks and through a greater emphasis on enhancing visitor experience and learning. The New Media Strategies and Investment Unit contributes to this effort by looking at emerging technologies that could attract new audiences and appeal to existing audiences.

Why Handheld Location-Based Technologies at Parks Canada?

Handheld location-based technologies seem, on the surface, to be a good fit for Parks Canada parks and sites. By combining a portable technology with the rich stories that we have to tell at our parks and sites, these devices appear to have the potential to attract new audiences while enhancing our visitors’ learning and experience. As they rely on satellite signals for location sensing, they seem well-suited for our outdoor sites, many of which are in remote areas. They don’t require the installation of any outdoor infrastructure, saving costs and preserving the integrity of our sites.

Two research projects provided additional impetus for this project. The successful European WebPark project, which took place from 2001-2005, proved that this technology functions well in remote areas, and demonstrated that visitors who used it increased both their time spent and awareness of landscape features on the trails where it was used (Dias, 2007). In 2007, a Parks Canada-led research project in Banff National Park determined that a wide range of visitors was interested in using this technology in national parks and national historic sites. Those who tested a prototype handheld tour of the Hoodoos Trail felt that it increased their learning about the trail and made their experience more enjoyable, and the majority was interested in trying similar devices at other Parks Canada locations (Parks Canada/ART Mobile Lab, 2007).

The New Media Unit felt that the best way to learn about the technology was to develop and evaluate our own projects. In summer 2007, the New Media Unit embarked on the Explora pilot project. This pilot consisted of the development and evaluation of handheld tours at two sites to answer two main questions:

- Can location-based technologies – using a combination of global positioning system technology, handheld computers and multimedia content – enhance visitor learning and experience at Parks Canada sites?

- Can projects using this technology be developed in a way that is sustainable for Parks Canada sites?

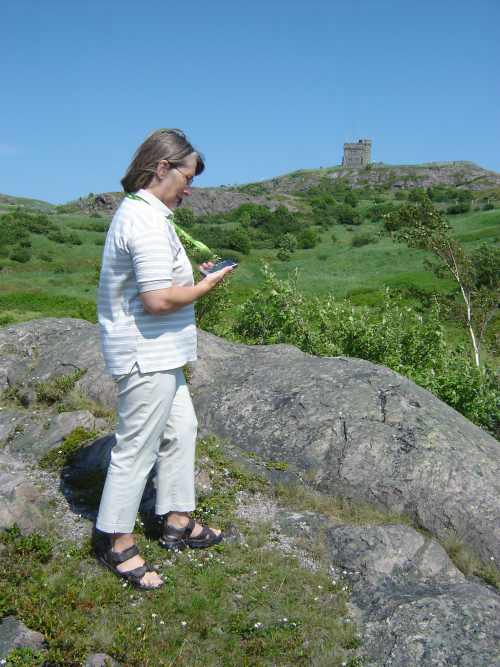

Fig 1: The Explora pilot project begins

Early Decisions Taken

If this technology were to be adopted, it would have to be sustainable at Parks Canada parks and historic sites. This led to a number of initial decisions.

- The pilot would use off-the-shelf GPS-enabled PDAs rather than proprietary hardware offered by a limited number of suppliers. If this technology were to be sustainable, it would have to run on as wide a variety of devices as possible, and would have to take advantage of the latest technology rather than being locked into a limited number of devices.

- Non-technical site staff, such as interpreters, would be responsible for creating and modifying content. Therefore, a user-friendly content management system and support for training and use of the CMS was required. Our approach would be a compromise between using free or more complex applications that could only be used by technical staff, and handing the entire production of the projects over to an outside firm.

- Multimedia content would be used, including images, text, audio and video.

- Parks Canada staff would be mentored by someone experienced with this technology

- We would document all phases and time required and gather feedback throughout the development process

- We would develop two pilot projects - one at a national park, and one at a national historic site - to determine the challenges and limitations for each type of site. This approach would build on the knowledge acquired during other similar projects, most of which had been undertaken at natural parks.

As this paper will demonstrate, all of these decisions were good ones and helped us achieve our objectives.

The Development Process

The pilot project kicked off in November 2007. Explora was completed and made available to the public in July 2008. This rapid progress was achieved thanks to the selection of appropriate sites, the involvement of highly motivated and skilled teams, including an expert mentor, and a tightly managed project development process.

1. Site selection

Of the many national parks and national historic sites that were interested in the pilot project, two sites were selected: Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site in Nova Scotia, and Signal Hill National Historic Site in Newfoundland and Labrador. These sites had the most important ingredients: physical, including short trails with a variety of points of interest, a practical location for handing out and managing the devices, and little or no signage on the trails; and human, including staff with the necessary skills, time available, and, above all, enthusiasm. They also had plenty of photographs, illustrations and other content assets readily available.

2. Pilot teams

Three teams were created: a core team at each site, as well as an extended team that oversaw and supported the core teams. Core team members included a project manager, content lead and content team, a GIS specialist, and IT support. Extended team members, all located at the National Office, included a pilot project manager from the New Media Team, a Chief Information Office representative, a Visitor Experience representative, and a Communications Lead. A final, essential, player joined the project as the technology supplier and product development mentor: Camineo, located in France, won the contract to provide this role.

3. Project phases

The project was divided into several key phases, each culminating in a milestone. All team members were kept abreast of the schedule and expectations for each phase, and the project managers and Camineo worked together to ensure deadlines were met. Key stages included:

- Project Initiation (Nov-Dec. 2007): Teams were created and met on-site in early December to be introduced to the project, the technology and the development process, and to walk the trails that were being considered. A broad group of site staff was brought into these meetings to ensure that there was acceptance and familiarity with the project. The meetings were followed up by the writing of the Project Initiation Document which articulated the project’s goal, objectives, target audience, description, preliminary budget and schedule, and project team roles and responsibilities.

Fig 2: Team members and site staff walked potential trails in December

- Project Brief (Dec. 2007-Jan. 2008): In December and January, team members finalized key messages, created cognitive, affective and behavioural objectives for their tours, finalized trails, and fleshed out the content for each route by elaborating on key points and identifying media. The Parks Canada GIS specialists worked with the team to identify geographic data requirements. The team’s ideas were gathered together in the Project Brief document for each site.

- Preliminary Interpretive Plan and Initial Tour Integration (January-March 2008): Teams finalized points of interest, marked final waypoints, wrote text, and identified and acquired or created media such as photos and illustrations. During this period, Camineo met with the teams for the first time, introduced their software and development process, and integrated the first tour’s content into the Camineo Maker content management system. GIS specialists created and tested maps, and developed a procedure to produce small, accurate maps that are visible on the small screen of the device.

- Initial Tour Testing (March-April): In April, teams tested the first tour and immediately noted the changes that had to be made. Everyone found this initial testing an eye-opening and useful experience. As a group, we decided upon the revisions and refinements we needed to make. In addition, team members learned how to use the Camineo Maker software. They received a one-day training session with Camineo, and then made regular use of ongoing support through a variety of means, including an on-line forum with Camineo.

- Final Tour Creation and Testing (April-July): For the last three months, teams completed the production and refinement of the content. They located and formatted missing images, sounds and video, edited and translated text, and frequently tested the tours on the trails. As well, they integrated all new content themselves. In early July, several team members at each site spent one intense week on the final testing of all of the content on the devices.

Fig 3: July - one-week final testing and validation period at each site

- Final delivery to visitors and pilot period (July-September): The devices were fully tested and ready for use in time for the launch date. For the next 2 months, visitors were invited to use the devices, which were available for loan at the Visitor Centre. An evaluator was present at each site to administer surveys and do observations. In addition, a logbook was kept at each site for visitor comments.

Results

The Explora project resulted in the development, in less than 8 months by staff that had no prior experience with this technology, of fully-operational, GPS-triggered tours that functioned on three hiking trails. The devices were used by over 1000 people of all ages, from the local area and beyond, both first-time and repeat visitors. Media interest was considerable, with several newspaper articles, radio and television reports about the project. Staff members were proud of their achievement and pleased to be able to offer this new product.

Description of the device and the user experience

The Explora device is a handheld PDA that features location-specific content, such as bilingual text, photos, illustrations, audio and video, that is both ‘pushed’ (automatically triggered by GPS) and ‘pulled’ (selected) by users. Content was created, sourced and formated by the project teams using the user-friendly Camineo Maker content management system. The content plays on the device using a program called Camineo Player.

Fig 4: The Explora device showing a sample of the Kejimkujik interface

Users wore the device on a lanyard around their necks. They interacted with the content through the device’s touch screen. After selecting their choice of English or French (Figure 5), users watched a tutorial, selected a trail, and started their hike along the trail. For the remainder of the hike they viewed the device each time they heard the sound trigger, and at any time could make selections from the touch screen.

Fig 5: Users selected their language from the initial language selection screen

Content included:

- Pushed ‘POIs’ - Each trail featured 20-30 automatic ‘pushed’ Points of Interest. These typically included text and an image related to the specific location, and often included links to a related audio, video or other text.

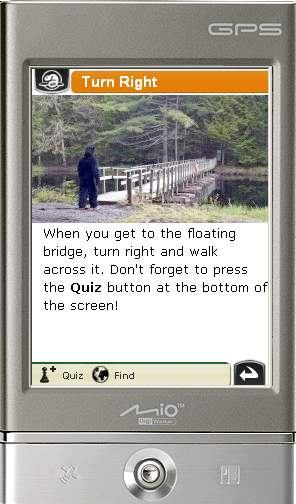

- Navigation Points - These pushed points (Figure 6) gave the users simple directions to help them navigate their way through the tour.

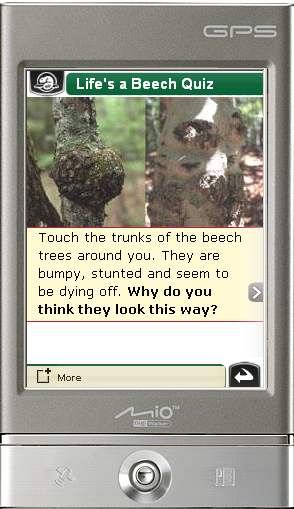

- Quizzes - There were several fun quiz questions (Figure 7) related to something that could be seen on each trail, with a point awarded for each correct answer. At the end of the route, visitors could find out their score. These were very popular and were accessed by most users.

- Maps - Users could always see their location on a map. In addition, they could move the map with their finger, and zoom in and out of the map. We included three scales: very far out, middle, and very close up to show the trail. We also included an aerial photo for each site.

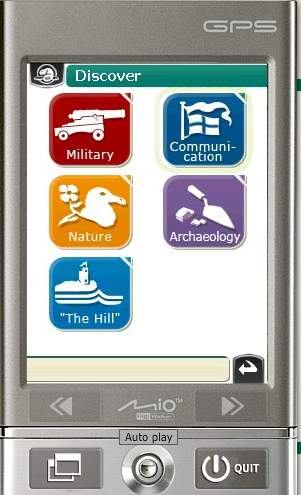

- Discover section - The Discover section (Figure 8) is like a field or reference guide, where users can choose to look at content organized by theme. Many of these content items are pushed points, and some are More, Audio or Video pages that can be selected from a pushed point. Categories included Flora, Fauna, People, The River (for Kejimkujik) and The Hill (for Signal Hill).

Fig 6: Navigation points clearly told visitors where to go

Fig 7: Quizzes were popular features

Fig 8: The Discover section functioned like a reference section

The device and how it performed

The Mio P360 was selected as the platform for this pilot as it met our requirements for commercial availability, Windows Mobile Operating System, affordability, robustness, a touch screen, sensitive GPS chip, multimedia capability, and a long-lasting rechargeable battery. We had 10 devices available for loan to visitors at each site. They proved durable and satisfactory for the pilot. One device had to be exchanged when it stopped functioning, while the others were operable throughout the pilot and suffered no more than a few small scratches and tiny dents to the casing.

Site and Project Descriptions

1. Signal Hill National Historic Site (“Signal Hill”)

Signal Hill, located in St John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, is nationally significant for its military and communications history. Well-visited by locals and tourists alike, it features historic buildings, archeological sites, dramatic hills, spectacular vistas and rocky cliffs bordered by the Atlantic Ocean. Two trails were selected for Explora tours: the Burma Road to Ladies’ Lookout Trail (2.8 km long) and The North Head Trail (3.6 km long). These trails both began and ended at the Visitor Centre, and took visitors past many historic structures and sites, up various staircases to the summit, and along cliffs that border the ocean. There were approximately 30 pushed points of interest on each trail, including an historic stone military barracks, a site where military families lived and gardened in the 19th century, the Cabot Tower, and a place where a military hospital once stood. Content included a panorama view of the barracks across the narrows, a video explaining how to read markings on British cannon, a photo of a cup that was found during an archeological dig, and an historic painting of the gates that once stood at the summit of Signal Hill.

Fig 9: A sample pushed point of interest from Signal Hill

2. Kejimkujik National Park and National Historic Site (“Kejimkujik”)

Kejimkujik is located in mainland Nova Scotia. This inland park features lakes and forests and is visited repeatedly by many local visitors as well as those from further away. The Beech Grove Trail was selected for the Explora tour. It is a 2 km circular trail that starts at the Visitor Centre, crosses the Mersey River, winds in a circuit along the river, up a drumlin, past endangered plants, back along the river and across the bridge. The theme of the route was change, and it featured 21 points of interest, including a drumlin, a tree with a hole formed by woodpeckers, and the place where an endangered orchid grows. Content includes a quiz about dragonflies, a video of brook trout jumping in the river, and an audio and slide show describing the lifestyle of the native inhabitants of the area before the park was established.

Fig 10: The Discover menu from Kejimkujik

Assessment of Sustainability

The pilot provided us with some positive and constructive answers to the question, “Can projects using this technology be developed in a way that is sustainable for our sites?” Staff successfully developed the content and learned to use the Camineo Maker software to integrate and update content. A forum and access to the software company enabled staff to pose and answer questions that allowed them to overcome challenges and continue their work. Site staff also successfully managed the devices throughout the pilot period. Several feedback sessions held with staff involved in the pilot indicated that staff were satisfied with their involvement and would welcome future projects. It was clear that staff skills were transferrable to this technology, and that developing content for this device is similar in many ways to developing content for other interpretive programs and products.

The time and costs required to develop the project were documented and appear reasonable. However, for this type of project to be truly sustainable, sites must consider the technology as a long-term investment with time and money allocated annually to maintain and update the equipment and content. A six-year life cycle maintenance plan has been drafted and will be provided to all Parks Canada sites interested in this technology.

User Evaluation

Social scientists at Parks Canada oversaw a research project to help us answer our main visitor-related questions. We wanted to know how visitors used the device, if the experience impacted visitor learning and experience positively, and how we could design the experience to maximize visitor experience and learning. We also wanted to know if and how much visitors would be willing to pay for such a device.

Methodology

We settled on a combination of qualitative and quantitative instruments in order to answer our questions. At both pilot sites, tally sheets recording basic user information for all users were filled out by visitor services staff. In addition, researchers administered a survey to a total of 272 visitors and performed observations of 65 visitors. Finally, all user actions and positions were logged by the devices in the data logs on each device.

What did we learn about visitor behavior?

The data logs (which recorded the location of all user actions as well as the location, date and time every 15 seconds for each user), together with the observation diaries, give us a good picture of how visitors actually used the devices. The main finding is that use was fairly consistent for all users, and followed the pattern we expected and hoped for. Typical use of the device included stopping at all ‘pushed’ points of interest (Figure 11), reading the text out loud to group members, looking for or pointing at the trail features mentioned in the text, and if there was a quiz, answering the quiz question. If an audio or video was offered as an option on the first page of a pushed point of interest, most visitors would select it. However, if content was only provided in the Discover menu, very few visitors selected it, and in some cases nobody selected it.

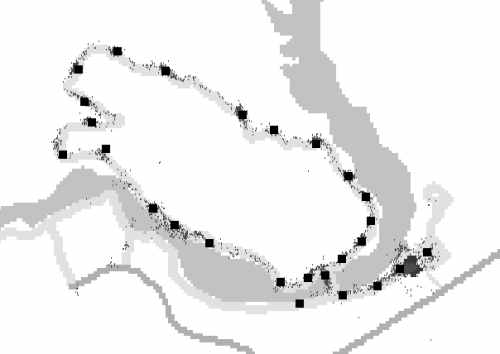

Fig 11: Kejimkujik data log map

This map from data logs at Kejimkujik’s Beech Grove Trail shows that users stopped at the pushed points of interest. The tiny dots show 16,621 user log points where the speed is 0 m/s (no speed), and the black squares represent the pushed points of interest.

What did we learn about visitor learning and satisfaction?

The surveys included a range of questions about satisfaction and learning. Overall, visitors reported that they learned something from their experience and noticed something that they would not have noticed without the device. Most could voice a specific theme or subject that they learned about, and many identified a specific trail feature that they were unaware of before. Most also reported that they found the experience enjoyable. Surprisingly for some, there was no significant difference in satisfaction between age groups or between males and females. Older users were, in general, as satisfied as younger visitors.

What did we learn about willingness to pay?

Over 75% of visitors were willing to pay. Of all those surveyed, 60% were willing to pay between $4 and $6 per half day.

Next Steps

We are satisfied with the pilot project, and feel that our main questions have now been sufficiently answered. Based on the results, we have decided to move from the pilot phase into a phase of facilitating the adoption of this technology across the Parks Canada system. Sites are being provided with information about the pilot and the technology, including the project review report and results of the data analysis. Other actions we are taking include the following:

- The technology will be used at the existing sites in summer 2009, and one or two new trails will be added at each site, incorporating lessons learned from the pilot.

- Toolkit and training development is underway to support new sites, and information is being prepared to help sites determine whether this technology is in fact a good choice for them. Explora team members are writing step-by-step development instructions, fact sheets and other guidelines for new sites. A workshop outline is also being developed. We are hoping to develop a community of practice so that experienced sites can coach new sites.

- We are investigating ways to secure a technology provider for all of Parks Canada by September 2009. We believe that the most efficient solution is to have a single technology provider that is available to all sites wishing to adopt this technology. Among other benefits, this will facilitate support for sites across the system, and will ensure sites can learn from and help each other.

- We are looking forward to testing out advances in the technology as they are available, such as being able to provide content that is downloadable to users’ own devices.

Overall Lessons Learned

- Ensure you get to know your various visitor groups and their interests, and cater to them. It is people in every age category, not just young people, who will use and enjoy this technology.

- Put your most important information right on the first page of each pushed location. The most visited content was the main pushed content. Everybody will read it. The next most visited content was quizzes, audio and video, so include fun elements and audiovisual elements. Putting a lot of information only in second or third layers of content, such as the Discover field guide, is not worth the effort for the general audience – they won’t go there.

- Provide clear maps. They are accessed frequently and need to be accurate and clearly visible on the small screen of a device. GIS expertise and data are needed to create these maps.

- Invest less in content at the end of a route by spreading points of interest out more sparsely and by keeping text short. Some content seems to be accessed less at the end of the trail.

- To develop a project, appropriate sites and enthusiastic teams are essential. You need enthusiastic and multi-skilled team members who aren’t afraid to try new things. You also need trails and facilities that meet requirements, such as receiving a strong GPS signal, having a visitor centre for device handout, and having trails without signage but with many visible points of interest.

- To ensure sustainability, site staff members need a user-friendly content management system and support in its use. Expert technical support for the content management and player software and overall project development is essential for a first project. This requirement could diminish as sites become more experienced using the software and as in-house support (such as a training program and a team of in-house experts) is developed.

- To gain buy-in and build excitement within a site’s staff, provide hands-on opportunities with the technology to a wide range of staff. We invited a wide range of site staff, including managers, office staff, operations staff and interpreters, to try out the technology early on and kept them aware of its development process by holding a number of information sessions. We also involved as many as possible in early walks on potential trails.

- Use the milestone approach to ensure all team members know what is required at each stage. Milestone documents ensured that all thinking had been done for each phase, and were useful reference documents for the team and communications documents for external use. In addition, all team members were aware of key milestones and ensured we stayed on schedule.

- Test the devices on the trail early and frequently. The more testing, the better. Read the text out loud and make sure it makes sense on location. Listen to the audio; watch the videos. Note your changes on the spot, make the changes, and try again. We found this iterative process showed us early in the process what worked and what didn’t, and ensured our content functioned properly and made sense on launch day.

- Depending on staff availability and the scale of the project, projects can be created in as little as 4 months, or up to just over 1 year. For a new pilot or a major new trail in a new area, a suggested timeline is: project initiation in spring; kickoff meeting in May; content development in summer; other milestones through fall, winter and spring; launch the following summer. For a small trail at a site with an existing project, you could initiate in October, do content development through fall and winter, and launch in July.

- Develop a small trail first to develop confidence and skills; then expand to a larger trail. This phased-in approach allowed our team members to assess their first efforts and collectively see the refinements that were required.

- Consider costs and staff time required over at least 6 years before committing to this technology. Sites need to ensure sufficient staff and resources to develop a new project, as well as to maintain and update content and devices over at least 6 years. It requires between 120 and 175 staff days to develop a first project, and requires one interpreter/content person for 4 months, a project manager throughout the process, and time from specialists such as content experts and GIS Specialists. Funds must be available annually for the software license, for replacing equipment, for development and delivery, and for content acquisition and development.

Conclusion

The Explora pilot project demonstrated that location-based technology can be a valuable addition to the interpretive offerings at Parks Canada parks and historic sites. It has broad appeal to existing visitors, and could be marketed in an effort to attract new visitors. Staff were able to use their skills and knowledge about their site to develop and modify the content, and a wide cross-section of visitors enjoyed and learned from the devices. By developing and evaluating our own projects, we have learned many lessons that will be useful for future projects. We hope that our experience will benefit others.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Parks Canada staff at Kejimkujik and Signal Hill, the Newfoundland East and Mainland Nova Scotia Field Units, the Atlantic and Quebec Service Centres and National Office for their cooperation and enthusiasm throughout this project. We would also like to extend our thanks to the Camineo team for their help every time we asked for it!

References

Dias, Eduardo Simao (2007). The Added Value of Contextual Information in Natural Areas: Measuring impacts of mobile environmental information. Amsterdam: vrije Universiteit.

Parks Canada/ART Mobile Lab (2008). Public evaluation of a handheld locative trail guide created by the ART Mobile Lab for Banff National Park. Banff: The Banff Centre.