Introduction

The visitors gather after dark. Strangers introduce themselves as they spread blankets on the ground. Children watch the flames of a campfire. A cheerful woman or man, wearing a uniform and a Stetson hat, tunes the guitar to get visitors’ attention. The park ranger sets the mood by teaching the group a song, which visitors sing in unison. Then the park ranger begins to reveal the park’s wonders that lie all around them, hidden in the darkness.

Campfire programs are as iconic to the United States National Park Service (USNPS, or NPS) as the park ranger hat. Local sites have their own variations. Visitors to Rock Creek Park may listen to a string quartet, while at Cape Cod National Seashore, visitors work together to draw a large map of the cape in the sand. But the basic elements remain consistent. Campfire programs attract young and old, not merely because the ranger knows so much about the park, but because visitors participate in the park’s mystery - even if they only gather as an audience. Families, couples and singles share a common experience on common ground, the kind of museum experience Falk (2008) describes as “deeply personal, intimately tied to each subject’s sense of identity.” Visitors become a part of, not apart from, the National Park. The values of park stewardship pass from ranger to visitor and from generation to generation.

This last point - inspiring a new generation of park stewards - is practically encoded in the agency’s DNA. The Organic Act of 1916, which founded the NPS, charges the agency with preserving natural and historic treasures for the enjoyment of the public “by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations” (NPS, 1916). Parks are charged with looking toward the future of the resources they protect.

Today, the Internet is the most obvious medium to engage a new generation of young adults and teens to support their parks. New technology has the added potential to attract new, younger and more diverse audiences to National Parks than we have today. Studies show African-Americans and Hispanics are less likely to visit National Parks than the general population, and more likely to feel unwelcome when they do visit (Solp, Hagan and Osterman, 2003).

But how can the Web convey the warmth of a campfire program? Can new technology transmit the excitement and intimacy of a National Park’s story to so-called “digital natives”?

In the spring and summer of 2008, the National Parks of New York Harbor Education Center (the Center) facilitated two video podcast projects. (The Center, which is managed and operated by Gateway National Recreation Area, helps National Parks in New York Harbor create education services which support state and local curriculum standards.) Each project used a different approach to attract “Millennials” (also called “digital natives” and “Gen Y,” short for “Generation Y”) to New York Harbor’s 23 NPS sites. One project placed videocameras into the hands of high school students. The other project relied on a professional documentarian to create a series of video podcasts about National Parks in New York Harbor. Each approach had its own challenges and rewards, and each points the agency to new ways it can interact with visitors.

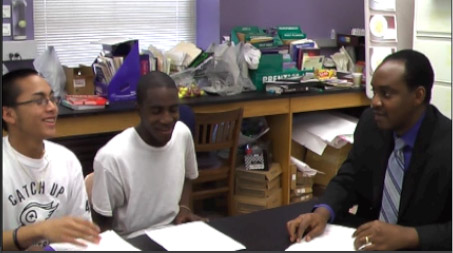

Fig 1: High school students interview science teacher Christopher Chieh, who immigrated from Liberia (http://www.nps.gov/npnh/photosmultimedia)

‘Digital Natives,’ the Web and the NPS

Both national reports and local NPS data confirm that young adults and teens use new technologies and expect such conveniences as part of their daily lives. A market research report by PhoKusWright, “The NEXTgen Traveler™” (Cudebec, 2008), studied how technology users of all ages make choices in their travel destinations. The report offers provocative data on how technology users, including ‘Gen Xers’ and ‘Millenials’, use the Web in their daily lives. (The parameters of these generations are debatable, but Gen Xers are often described as those born between 1964-1980, with Millenials born between 1980-2000.)

- 71% use the Internet to search for travel information

- 59% download or stream video, including 26% downloading video podcasts

- 56% visit MySpace (a social networking Web site) regularly

- 34% share videos via YouTube

- 26% use Photobucket, while 17% use Flickr (two photosharing Web sites)

- 45% write reviews about movies, music, etc. on-line, with 10% writing their own blogs

- Only 14% report not participating in any social networking, sharing or community-oriented sites

Young adults obviously use the Web to make travel decisions and to gather content. But they also use interactive, many-to-many tools such as social networking sites, blogs and photo sharing. The Web is not merely a tool used to retrieve content, but also a space where young people share both content and comments. This has profound implications for museums and parks.

For parks and museums, though, the figures are less hopeful. While 74% took one to three leisure trips in the past year, visiting a national or state park attracted only 11%. Cultural vacations and educational vacations scored still lower, at 9% and 7%.

Are younger people uninterested in parks and cultural institutions, or are such destinations merely off their radar? Can parks and museums increase their visibility and visitation by a more savvy presence on the Web? If so, what forms should that presence take?

The NPS has paid increasing attention to ‘Gen Y’. A focus group of students at Johnson & Wales University (Drohan, 2007) visited National Parks in their area and surfed park Web sites. They gave their recommendations at the 2007 Northeast Region’s Chiefs of Interpretation Conference held in Providence, Rhode Island. The group recommended increased electronic communication to reach young people, specifically podcasts, e-tours and cellphone tours. They also mentioned that young visitors will feel more connected with park rangers closer to their age, staff who may be able to present information in ways that appeal to their generation. A focus group of students from Siena College suggested testimonials about a park from other young adults, as well as NPS presence on social networking sites such as the popular sites MySpace and Facebook.

Dr. Mary C. Lynn, Professor of American Studies at Skidmore College, facilitated a workshop at Saratoga National Historical Park on Gen Y. She noted (Lynn, 2007) that generalizations about an entire generation should be balanced with an understanding that gender, ethnic and class differences must also be considered. Nonetheless, she observed that many in Gen Y:

- Are increasingly separated from nature, despite an increased environmental awareness and interest;

- Spend more time indoors, often while using new technologies;

- Want interactivity, quick feedback, choices, flexibility;

- May have less exposure to National Parks due to a busy, highly structured family life, which places children in organized group activities while parents work.

Young adults in New York City offer an interesting look at the perception of National Parks, thanks to the city’s ethnic diversity. Dr. William Kornblum, Professor of Sociology at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, conducted a focus group of CUNY undergraduates as part of the workshop “Digital Natives and Analog Parks: Engaging Young Adults” (Kornblum, 2008).

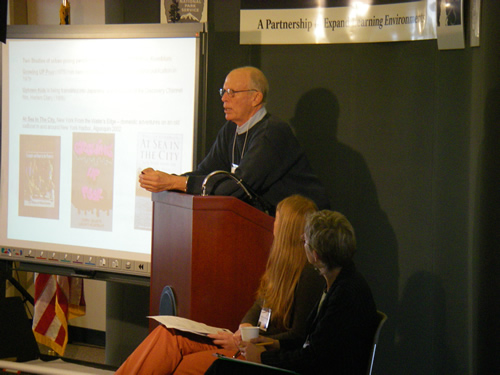

Fig 2: William Kornblum, Professor of Sociology at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, shares the findings of his survey of CUNY students

Kornblum reported that nearly 40% of young adults in New York City speak a language other than English at home. Three of every four survey participants report being introduced to a National Park, either by visiting a New York Harbor park (36%), via a television show (36%) or the Internet (12%). Students rated their interest level in visiting a National Park as medium (26%), relatively high (46%) or high (27%). They stated that they were most likely to hear about new activities from the Internet (33%), newspapers (28%), friends (23%), teachers (9%) and family (7%). Kornblum concludes that young adults “will become a vanguard of diversity in uses of the region’s NPS facilities in the future.” A more sophisticated Web presence would attract them to visit National Parks.

However, as of this writing, fewer than two dozen NPS units offer podcasts (audio or video) on iTunes. While NPS unit Web sites now have a uniform appearance (Stanton, 2001), individual park sites are responsible for updating their Web content. It may be useful to think of the NPS as a confederation of small museums within a national framework. Only around 20,000 full time employees work for the agency, spread across 391 units from the Virgin Islands to American Samoa (www.nps.gov). Understandably, parks spend their limited budgets and resources on walk-in visitor services and infrastructure.

Cobell v. Salazar, a class action lawsuit brought by Native Americans against the US Department of the Interior (DOI, which includes the NPS), may also have had an inadvertent chilling effect on Web-based innovations. Now in its twelfth year, the lawsuit alleges that DOI mismanaged money accounts for Native Americans. This includes alleged mismanagement of electronic records. In December 2001, the Federal judge in the case ordered many DOI Web sites and e-mail addresses to be shut down until they met enhanced security standards. By mid-2002 the NPS went back on-line, but some DOI offices were not reconnected until mid-2008 (http://www.doi.gov/bia/). As a result, agency employees may perceive new technologies not only as difficult to master, but also as risky and insecure. In this writer’s experience, park rangers respond to news about Web innovations by asking, “Are we allowed to do that?”

Perhaps, then, placing video cameras in the hands of high school students might seem a bit less risky after all.

Student-Created Content: The Save Our History™ Project

In March 2008, juniors at the College of Staten Island High School for International Studies (CSIHSIS) videotaped interviews with immigrants living in their community. This was the culmination of a year-long focus on immigration, titled “Immigrant Experiences: From Ellis Island to Staten Island.” The project was funded by a grant from the History Channel’s Save Our History™ program (http://www.history.com/minisites/saveourhistory).

Aligning the interests and goals of all partners in a project is, when it works well, a highly choreographed dance. The partners in this project had interlinking relationships. Statue of Liberty National Monument (which includes Ellis Island) is another NPS unit in New York Harbor. Save Ellis Island is a cooperative association helping to preserve New Jersey’s section of Ellis Island. The Center has a formal partnership with the College of Staten Island, which in turn helped create CSIHSIS as a charter school. All partners contributed time, staff and space to the project.

Fig 3: Who’s right? At the NPNH Education Center, students read official records that contradict an Ellis Island immigrant’s oral history

The inspiration for students interviewing modern-day immigrants came from an ongoing oral history project at Ellis Island with immigrants who had passed through the island during its years of operation (1892-1954). The activity was the culmination of a year-long focus on immigration in US History class. At the same time, students in Technology class (a half-year course) learned how to create and edit videos. Partner organizations brought in speakers, from park rangers to professors. They taught students how to take documentary photographs, how to conduct oral histories and how to evaluate primary sources.

Teams of students located Staten Island residents who had immigrated to the US, researched the person’s country of origin, and sat down for an interview. Originally, the Center had wanted students to engage communities actively, with flyers and visits to community centers. Instead, students interviewed relatives, teachers and in at least one case, a co-worker at a restaurant. But this did not detract from the project at all. Indeed, the project gave several students the chance to discuss family history with their mothers, fathers and grandparents for the first time and to have new conversations with their teachers. Students interviewed immigrants from China, Cuba, Ghana, Hong Kong, Ireland, Lebanon, Liberia, Pakistan, Poland and South Korea. (One team chose to interview a migrant from Puerto Rico.)

Fig 4: George Kaluski interviews his grandmother, Margaret Kubasczyk, whose Polish family narrowly escaped death from the German Army in World War II

Before any filming began, we contacted the NPS solicitor. Several forms needed to be created and signed first. Some parents, out of concern for their children’s safety, do not want their child’s face on the Internet. The NPS solicitor approved the language for photo/video release forms which parents needed to sign for their minor children prior to the filming. Since agency-created material belongs to the public domain, students and parents also had to agree to waive claim to copyright control. Some interview subjects expressed opinions about politics; therefore each video began with a disclaimer. If we did not receive all permission forms, we did not place a video on exhibit or on the Web.

Students had been encouraged to check out the school’s videocameras, tripods, MiniDVs and microphones, some of which were purchased specifically for the project. However, both audio and video technical quality varied widely. Several students grabbed the family videocamera and recorded on to Memory Sticks, creating grainy videos, or filmed next to noisy refrigerators and busy stairs. Out of fifteen student team projects, nine were chosen by the school as good enough for exhibition, based on both the quality of student questions and the technical qualities of the recording.

But the content of the videos ranged from good to astonishing. Students had clearly studied the home countries of the immigrants and asked thoughtful, intelligent questions. Immigrants clearly were at ease with the students, sharing many personal details of their old and new lives in the US. Indeed, they may have been more open with answering students’ questions than they would have been sitting with an academic oral historian. Interviews were as short as ten minutes or as long as an hour.

An example: George Kaluski interviewed his grandmother, Margaret Kubasczyk, who immigrated from Poland after her husband’s involvement with the Solidarity movement made life even more difficult in the Communist state. In her interview, she recalled an incident during her childhood, where German soldiers were burning their village. “I started kissing this German soldier’s hand,” she remembered, “saying, in Polish, ‘Please, please let us go to my grandmother.’

Immigrants often had advice for the students. Christopher Chieh, a science teacher at CSIHSIS, compared his experience fleeing Liberia with human tragedies closer here in the US:

Being a refugee is not something you plan for... Hurricane Katrina came and people were internally displaced. You must prepare for the unexpected ... always keep your head up high, be very optimistic, and continue working hard and believe in yourself, believe in your family values... and you will definitely make it. (http://www.nps.gov/npnh/photosmultimedia)

Some teams preferred one on-camera interviewer, while the team that interviewed Debbie Goon took turns asking questions, even calling out follow-up questions off-camera. Goon revealed that she “cried for two weeks straight” when she started attending school on the lower east side of Manhattan until another Chinese girl in class started to mentor her.

The nine videos chosen were further edited down to podcast size by a professional film editor. The Center designed a temporary exhibit at Ellis Island and featured the students’ work, including the nine videos; the exhibit was on display in June and July 2008. Close to half a million people visited the island during those two months alone. A formal opening took place at Ellis Island on Saturday, June 7. In addition to text and photos, visitors could select for themselves any of the nine video interviews they wanted to watch. Observers noticed that families often chose to watch videos of people from the same home countries as themselves. The panel featured the immigrant’s name as well as the name and flag of their country of origin.

Fig 5: Visitors to Ellis Island choose an immigrant to watch

For preservation after the exhibit was taken down, copies and transcripts of the edited interviews were donated to four local history institutions: the Bob Hope Immigration Archives at Ellis Island; the archives of the College of Staten Island; the Staten Island Historical Society; and the Staten Island Museum.

The good work of students and partners alike earned the Save Our History Preservation Award, given annually to the grant recipient that preserves a significant aspect of community history or heritage. In addition to its monetary component, the award allowed both teachers and four students to attend the award ceremony in Washington, DC.

Creating Videos = Creating Meaning?

John Dewey (1916) reminds us that while experience alone is “primarily an active/passive affair, it is not primarily cognitive. But…the measure of the value of an experience… includes recognition in the degree in which it is cumulative, or amounts to something, or has meaning.” Did the experience of creating videos have meaning for our students? If so, why?

In November and again in June, students filled out Personal Meaning Maps (PMMs) which were evaluated by Claudia Ocello, formerly of Save Ellis Island. Out of 58 PMMs collected initially in November, 24 (41%) made some changes/additions to their PMMs. Of the 41% that made changes or additions, 21% exhibited evidence of increased breadth of knowledge. They added phrases or words such as hardship, deportation, positive and negative effects and interviews. Examples included adding drawings of artifacts seen on field trips or of dollar signs; crossing out the word boat and replacing it with ship. A deeper content knowledge was demonstrated by 17% by using words such as no Medicare, illness and health checks. Some expressed how the interview they did “shed light on what it was like to come from another country,” in the words of one student.

Why did students learn from the year-long project? Perhaps it was because they now associated immigration with individuals they knew - teachers, workmates, family members. But the creation of the videos themselves almost certainly added meaning to the project for students. Levy (2008) observes, “When students work on curriculum standards in the context of producing a genuine product for an authentic audience, the result is enhanced achievement in content-area knowledge, literacy, craftsmanship and character.” Students knew that their videos would go on the Web.

The Save Our History™ project has terrific potential for the NPS. By “deputizing” high school students to collect, preserve and present history to the public, we invite them to host their own virtual “campfire programs.” The agency is sharing its intellectual hegemony with teenagers and with the immigrants who agreed to be interviewed. This is a bold step toward engaging the agency with schools, students and local communities. Several students also chose to create portfolio projects on immigration.

Like all bold steps, the project faltered at times. As stated earlier, the quality of the videos varied widely. The initial intent of the project was too ambitious to match the pace of curriculum. We wanted students to shoot part of their videos at Ellis Island, drawing a direct comparison between the recent immigrant and an Ellis Island immigrant from the park’s Oral History Project. The videos could have been used by visitors while touring Ellis Island itself. Although we met with each group of students and matched them all with an Ellis Island immigrant oral history, the video component of the project ended with the modern immigrant interviews. It is unclear why the project stalled there. Were there tensions within the school that all parties were unaware of, or was it simply too late in the school year to do much more? Or did competing events, such as a trip to Germany, overwhelm the students?

Fig. 6: Students practising their interview and video skills

In retrospect, the project was more daunting than perhaps any partner had realized. While the college and the Center had a prior relationship, the Center and CSIHSIS had never worked together before. Monthly conference calls took place among the partners to resolve outstanding issues, but front-line staff probably needed to talk to each other more frequently about integrating curriculum with the project’s timetable. One example: the history class was year-long, while the technology class was a half-year. The two teachers also lacked a common meeting time. How could they coordinate lesson plans? It might have been better for the school and the Center to work together on a smaller project first, so that each had a better grasp of the other’s needs and abilities. Also, the earlier a detailed plan is in place, the easier on all parties.

Finally, a project as rich and complex as this demands student buy-in. In retrospect, we made the classic teacherly mistake of frontloading content and skills first, saving the “fun stuff” until late in the school year. By then, perceptions were set about the project, one way or the other. Next time, we would give students more choice and autonomy. We would ask them to define what they wanted to learn - to write their own “essential question.” Ironically, had we ceded more control to students at the beginning, we might have come closer to our original expectations.

Hiring An Expert: The More Traditional Route

Issues of content and quality are much easier to address when the museum or park pays someone else to do the work. In the summer of 2008 the Center, in contract with Heritage Partners, Inc., hired Ducat Media to create a series of video podcasts. Vivian Ducat is the executive producer and principal of Ducat Media LLC, a documentary and multimedia production and design company creating projects for museums, universities and other cultural institutions. The series would feature different aspects of some of the National Parks in New York Harbor. The entire schedule was ten weeks, from preparation to final cut. This compressed schedule had its advantages: it kept everyone on task, while contractors knew when they were free to take on other projects.

While this project seems at first quite different from the Save Our History™ project, there are important parallels. First, each video project intended to attract young people to NPS sites through the Internet. Second, oral histories are not unlike documentaries. Both involved collaborative efforts between interviewer and subject, with an “expert” answering questions (given either on-camera or off-camera) and the shaping of content via video editing.

Ducat, a former reporter for National Public Radio, moved into documentary films because she wanted to tell stories visually. She eschewed storyboarding the videos but still framed the videos in a traditional documentary format, rather than a fast-cut, looser, post-MTV style. She asked rangers, partners and volunteers questions off-camera, with her questions cut out of the final product. Answers by the “experts” were intercut with moving and still images.

The initial interview meetings began in mid-July, weeks before any filming occurred. Ducat visited each of the six units, along with an NPS employee of the Center. NPS staff sometimes approached these meetings nervously. They were unfamiliar with new technologies and may have been wary of letting an “outsider” reshape their site’s narrative. But Ducat quickly put them at ease. She made it clear that NPS expertise would guide her editing decisions by asking question after question from site staff about the park resource. What stories did they themselves find the most compelling? Employees and volunteers realized they were in their familiar roles, as storytellers, and opened up to the project.

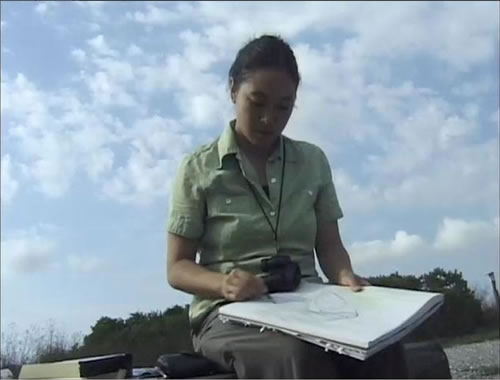

Fig 7: Park Ranger Anne Yen sketches a heron at Jamaica Bay

Each video included three to six speakers: park rangers, volunteers, professors at partner colleges and supervisors. Whenever possible, younger people were featured on camera to present content and to share their enthusiasm about the parks. Park Ranger Anne Yen sketched herons while off-duty. She observed:

Jamaica Bay is an amazing place to draw birds because there’s so much variety, there’s so many birds, coming and going... there’s, I think, over 350 species of birds, and it changes throughout the seasons, so you’ll never get bored.

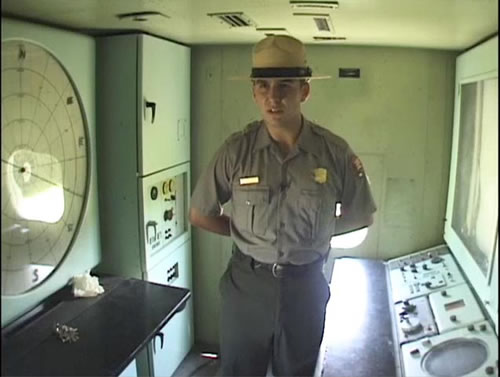

Videos allowed park sites to highlight unfamiliar resources. Sandy Hook chose not to feature its popular beaches, visited by two million people per year, instead focusing on its salt marsh and holly forest. Hook’s video on military history revealed the former presence of nuclear missiles. In a cramped room surrounded by dials, switches and buttons, Park Ranger Tom Minton explains the choice a battery commander would face if an enemy bomber violated US airspace:

[At] the moment of readiness he would throw the switch and release the warhead. [The] Missile would be on its way down range, and... when the interception clock clicked to zero you would throw this switch here, manually detonating a nuclear warhead over American home soil.

Fig 8: At Sandy Hook, Park Ranger Tom Minton shows the room where Army soldiers could have launched a nuclear attack

One video featured a team of ‘citizen scientists,’ led by Professor Russell Burke of Hofstra University, monitoring diamondback terrapins at Jamaica Bay. Shannon Ronquillo, a high school student and NPS volunteer, noted her surprise that a natural area like Jamaica Bay could exist in the boroughs of New York City. “Once you enter this place it’s like - it’s like you forget... that right over there is Manhattan, you just forget. It looks like you’re somewhere else.”

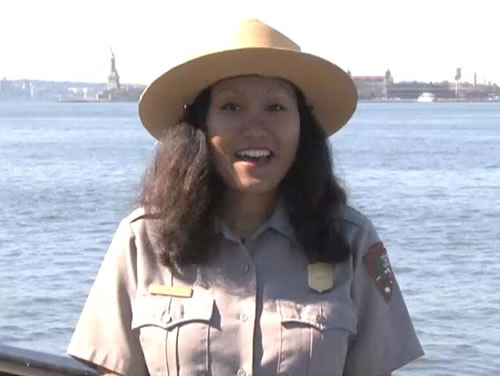

Over 40 hours of filming took place - enough material that an extra video was added to the project, bringing the total to 12. As filming progressed, some sites added employees to be interviewed. The result was a richer, denser narrative, but it also added to the overall cost of filming, transcribing and editing. This heterogeneous voice followed the documentary tradition more than the campfire talk tradition, where one speaker is generally the ‘expert’. Gloria C.A. Lee, a young park ranger, was chosen as ‘host’ of the series, welcoming visitors to New York’s National Parks. Her deft mix of friendliness and expertise set the tone perfectly.

Fig 9: Park Ranger Gloria C.A. Lee welcomes virtual visitors to the video series “National Parks in Your Pocket”

By mid-September, all twelve videos had passed from rough cut to review process to final cut. The voice of the NPS was unmistakable, delivered by uniformed park rangers and volunteers as in a traditional campfire program. But Ducat’s editing choices shaped the raw footage into coherent, unified narratives. While the final products may look like a well-made NPS production, they were in fact collaborative creations between NPS staff, partners and volunteers on the one hand and Ducat, her cameraman David Gaynes and video editor Michael Culyba on the other.

But will these videos appeal to young people? It is too soon to tell, and it will be difficult to tell. Currently, the NPS can track hits on Windows Media video files (.WMV) but not Quicktime (.MOV) or other formats. The videos included many young faces, but lacked prior input from young people. If time had permitted, a focus group of teens and young adults might have offered helpful suggestions. But anything created by the NPS must also be consistent with its established identity. Museums of modern art can splash pinks and oranges throughout their Web sites because modern art itself uses these colors. If the NPS traded its earth tones for electric blue and hot pink it would seem inauthentic, even condescending, to the audience we hope to attract.

For the NPS, video podcasts and having an engaging Web presence are necessary steps in bringing our resources and our stories to new audiences. But if the Web is indeed a cool medium, then content alone cannot make a virtual visitor warm towards a National Park. For a generation that writes blogs, uploads photos and meets new friends via social networking sites, passive content will not be enough to engage them. To approach the excitement of a campfire program, park Web sites must also engage visitors actively, in real time, with real people.

Fig 10: Liz Reif, graduate student at Hofstra University, points out swimming terrapins to high school student Shannon Ronquillo

Towards a ‘Virtual Campfire’

Nothing will replace visiting a real park in the flesh. The screen simply cannot convey the depth of the Grand Canyon, the rugged heights of the Rocky Mountains or the solemnity of the battlefield at Gettysburg. On-line experiences can engage virtual visitors in active participation. A video podcast will never feel like hiking a mountain trail or seining in the Atlantic, but it can take you to these pristine places.

The NPS can draw upon lessons learned in both video projects. The work by Ducat Media sets a high standard for the technical quality of new video podcasts. Now, NPS employees will have the much harder task of learning how to create similar results. Ducat’s documentary style can also guide NPS podcasts away from the hegemony of the lone expert toward a more inclusive approach, with multiple voices and opinions. College students or community members can make their own videos, combining the content knowledge of park rangers with input from park volunteers and users. Media projects using the documentary approach can create much more than Web content; they can build bridges between local NPS sites and their neighbors.

The Save Our History™ project holds even more potential to share our knowledge and authority, our meaning making, with others. Partnerships with schools and students take a great deal of care and attention - they are not ways to accomplish tasks quickly - but the payoff is enhanced community involvement, more provocative interpretation and, ultimately, stewardship of these resources by the next generation.

At the virtual campfire, visitors will do more than sit on benches and warm themselves. They will gather the fuel, select the songs and sing in harmony. The NPS, like museums in general, must find ways to create unique experiences on-line, foster live interaction with and among visitors, allow visitors to contribute content and to meet each other in a safe virtual gathering space. Kelly (2008) observes:

We are becoming people of the screen... On the screen, the subjective again trumps the objective. The past is a rush of data streams cut and rearranged into a new mashup, while truth is something you assemble yourself on your own screen as you jump from link to link.

As we shift “from book fluency to screen fluency, from literacy to visuality,” the viewer is no longer a passive consumer of content but an active participant in content reorganization. Creating content in a visual format is an important first step to attract a new generation. The next step requires museums to empower their audiences more than ever. Museums and parks alike

could use social media to create or improve popular knowledge-sharing networks, in which cultural participants share images, information, and experiences through communities. By promoting user-generated content, museums could enable cultural participants to be both critics and creators of digital culture. (Russo, Watkins, Kelly and Chan, 2008)

Museums are not classrooms in the traditional mode; visitors, in the flesh or on-line, are not students seated in rows. Visitors create their own interpretive “mashup” based on the content museums offer. John Falk (2006) warns us that museums should not ignore this

out of fear of being unable to control the results.... Such action (or inaction) ignores the human realities of how meaning is constructed and how museums currently are used by the public to support personal growth and development.

This will challenge both the traditions of the NPS and its circumspection as an agency. At this writing, NPS Web sites do not have blogs where the public can ask questions or make comments. Employees cannot access blogs on their work computers, nor social networking sites, not even YouTube. The NPS has a lot to learn technologically, but learning new skills in the name of constructivist pedagogy is truly daunting.

Paradoxically, the traditions of our campfire programs can help the agency as it embraces new technologies and new interpretive approaches. What made the campfire program so joyful, so memorable? Ultimately, it was not the campfire itself, nor the ranger’s ability to entertain a willing audience. Visitors attend campfire programs because they want a unique social experience and because they trust the Park Ranger’s knowledge of the resource. NPS expertise and visitor interest come together to create a social gathering space, where visitors can meet, ask questions and share their knowledge and experiences.

Bruce McHenry, a retired regional chief of interpretation whose father gave campfire talks in the 1930s at the Grand Canyon and Rock Creek Park, has thought his entire life about how parks can engage with citizens. He views new technology as an extension of NPS traditions and methods. “The computer,” he states confidently, “is the campfire of today.” It is up to NPS employees to light that fire.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to NPS volunteer Bruce McHenry and Park Ranger Dan Meharg for discussion of the campfire tradition and its possible intersections with new interpretive technologies. Thanks to NPS employees Neal Herbert and Karen Hecker of Canyonlands National Park for lengthy discussions about how they created the delightful video podcast series “Inside Canyonlands.” Thanks to Claudia Ocello and Tom Bumbera for reviewing the text in draft form.

References

Cudebec, Jennifer, Greg Dunn, Carroll Rheen & Lorraine Sileo (2008). The NEXTgen Traveler. Sherman, CT: Ypartnership and PhoCusWright, Inc. Copyright held by PhoKusWright, Inc.

Dewey, John (1916). Democracy and Education. Consulted January 15, 2009. http://www.ilt.columbia.edu/Publications/Projects/digitexts/dewey/d_e/chapter11.html

Drohan, Kathleen and others (2007). Though the eyes of youth: How the National Park Service can better engage Generation Y.

Falk, John H. (2006). “An identity-centered approach to understanding museum learning”. Curator 49, 161.

Falk, John H. (2008). “Calling all spiritual pilgrims: Identity in the museum experience”. Museum 87/1, 62-67. Consulted January 21, 2009. http://aam-us.org/pubs/mn/spiritual.cfm

Kelly, Kevin (2008). “Becoming screen literate”. New York Times Magazine 11.23.2008, published Friday, 21-Nov-2008. consulted January 15, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/23/magazine/23wwln-future-t.html

Kornblum, William (2008). Digital natives and national parks. New York: City University of New York.

Levy, Steven (2008). “The power of audience”. Educational Leadership, 66/3, 74-79.

Lynn, Mary C. (2007). Who is Gen-Y and why should I care? Findings from the “Generation Y” Workshop held at Saratoga National Historical Park, March 2007.

The National Park Service Organic Act: An Act to establish a National Park Service, and for other purposes. 1916, last updated Tuesday, 26-Feb-2008 12:20:08 EST. Consulted January 16, 2009. http://www.nps.gov/legacy/organic-act.htm

Russo, Angelina & Jerry Watkins, Lynda Kelly and Sebastian Chan (2008). “Participatory communication with social media”. Curator 51, 28.

Solop, Frederic I., Kristi K. Hagan & David Ostergren (2003). The National Park Service comprehensive study of the American public: Ethnic and racial diversity of National Park System visitors and non-visitors. Flagstaff, AZ: Northern Arizona University.

Stanton, Robert (2001). Director’s Order 70: Internet and intranet usage. Consulted January 15, 2009. http://www.nps.gov/policy/DOrders/DOrder70.html