|

|

This 'real' exhibition opened at the museum on Israel's 50th Independence Day, and traced the manifold incarnations and interpretations of the seven-branched candelabrum, from Biblical sacred object to national emblem, as represented in objects from the Museum's extensive collections of archeology, Judaica, and the fine arts, and through icons from institutions world wide. This offered an opportunity to design new and exciting online activities, incorporating the real time interactive component while drawing on works from a cross-section of the museum's permanent collections.

Designing the Project

It was clear from the beginning that we would be devising two routes for the 'Galim' website, one for the student and the other for the teacher. Students are introduced to the introductory online game with a dialog in comics; Lior and Liora, two illustrated heroes, invite the students to join them in resolving riddles and paradoxes.

| Fig. 3: Lior and Liora, cartoon designed by Yotam Bezalel. |

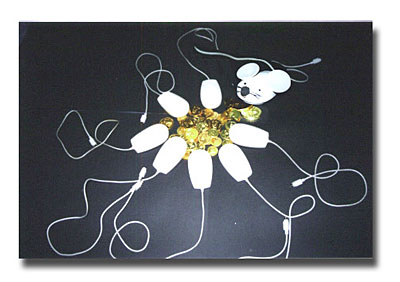

To discover what in the exhibition is attracting the mice in the gallery, the teacher hands out curators' cards (from the teacher's site) and guides the class in collating types of material used in the exhibits. When the group decides on why the mice have invaded the gallery, they then send in their solutions to the curator at the museum. At the end of the first quest: a correct response to 'the Mice Mystery' is sent into the museum via e-mail and the 'real' curator releases the new password (with a personal letter of encouragement) also via e-mail and the game develops.

| Fig. 4: The Mouse | Mystery

While students are actively seeking out further solutions to the challenges in the 3D gallery, the teachers access a password-protected, online program, which provides background information through appropriate texts and teaching material, such as the printable curators' cards. Teachers may print out worksheets from the site, ready to be handed out to the students in the classroom, as well as ideas for promoting discussion, and focused projects for the students in the classroom or at home.

| Fig. 5: Printable on-line worksheet, designed by Nehama Forster, Resnick Teachers' Training Center. |

The 'Virtual Menorah' includes games and projects that focus on symbolism, design, and historical contexts of the collections in the galleries and are the thematic envelope for the myriad activities that extend over many topics.

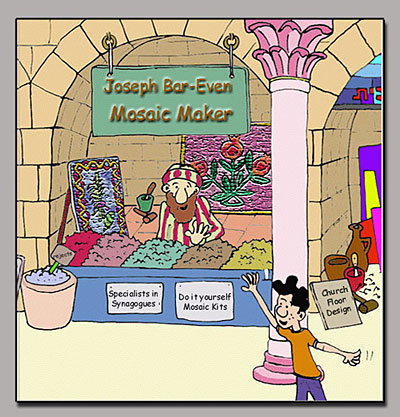

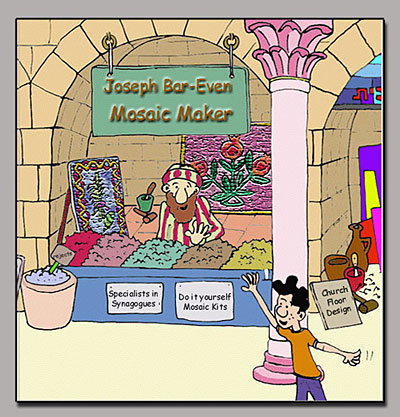

Another part of the 'Virtual Menorah' includes an online trivia game that rewards the students with 18 printable images, parts of a puzzle. The game is accessed via illustrations of three streets: a Roman Cardo, a modern day shopping mall and a futuristic shopping space.

| Fig. 6: Shop from the Cardo, cartoon designed by Yotam Bezalel. |

Hot spots hidden in the shops link to pop-up windows with questions and the correct answer leads the student to the next window where they can download one part of a puzzle. As the puzzle pieces are accumulated and the epigram and image completed, the whole picture can then be glued together, sent into the museum where the class receives a prize for their efforts.

The 'Galim' team at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, headed by Dudu Rashti and Galit Nadav included: graphic designer, web designers, pedagogic advisors, School Principals and teachers working with the project in the classroom. The team met on a regular basis with the content providers: museum educators and web content developers such as the Israel Museum and other organizations taking part in the project. At the Israel Museum I worked on the Museum@school site as the Curator of Multimedia in collaboration with Aliza Bezalel, Curator of Education. Over several ¶ months, concepts were developed and presented to the group and both practical and theoretical issues were worked out together. Throughout the summer of '98, teachers from schools in the pilot project received workshops in Internet basics, such as browsers, e-mail and 'Galim' specifics, provided by the Hebrew University 'Galim' team. The teachers then went on to meet the content providers in a series of workshops, each partner presenting his part of the project. During the workshop at the Israel Museum Multimedia Unit, teachers ran through the program online with some adopting the role of teacher while others became students.

The workshops provided valuable testing opportunities for problem-solving prior to the launch deadline.

The Launch

The 'Galim' site provides the shared environment that is now accessible to all schools and offers many resources for students, a teachers room, parent query area, reading area and public bulletin boards for all joint activities between the students, schools, and contributing organizations.

It became apparent to the Israel Museum Education Wing that the Museum@school project greatly benefited by joining forces and pooling resources both with The Hebrew University, Jerusalem and other cultural institutions in Israel, which at this moment includes, the Bible Land Museum Jerusalem, the Jerusalem Biblical Zoo, and the Center for Human Rights, Tel Aviv.

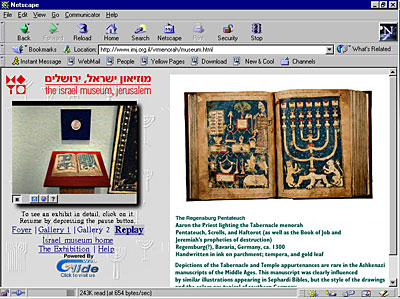

| Fig. 7: Screen shot of the "Galim" site. |

Through this joint platform, we have been able to create a

broad-based environment for local elementary school students. now in its pilot year, working with seven local schools in Jerusalem - to be extended nationally next year. Each institution comes with its own educational experience after working together to create a comprehensive and interactive program which, even at this early stage, appears to be an enticing challenge for both students and teachers.

It is clear that both elementary and senior students are already out there, surfing the net, and often spend many hours at home on enticing online games and jazzy web sites. In the school we must offer equally engrossing activities for these students, but with content that will contribute to earning activities and self growth. The Internet is an ideal stage for such 'edutainment'-like experiences, a new hybrid (a blend of educational activity liberally sprinkled with a portion of entertainment, or vice-versa), and museums or museum partnerships are ideally positioned to provide the rich content that is so sadly lacking on the Internet.

Net tools, such as e-mail, accessing password protected areas, and interactive games encourage students to link and think about the questions posed and contribute to his or her developing skill sets a fluency to navigate a networked environment.

As museum educators, during a real museum visit, we try to empower our visitors with hands ÷on and minds on activities, and encourage him or her to take an active role during the visit, often giving them an opportunity to ask questions and to engage in spontaneous discussions while standing in front of the collections. In addition, we create exhibits that actively stimulate the visitor to interact with the display, as often found in a childrens' museum. By gaining our visitors' personal involvement verbally or physically, we are assisting him in internalizing the experience at a level that is appropriate for him, extending his personal visual and conceptual vocabulary and ideally enabling him to reach a further level of understanding about the world around him through the museum visit.

This valuable educational experience, gleaned through a tradition of working with school visitors in the real gallery may be easily adapted and transformed into parallel digital activities over the Internet, via games, challenges and online discussions in addition to provision of appropriate teachers resources. We are already reaching new audiences as well as providing the remote students a direct connection to the museum and an expert and immediate response to their queries. Even in these early days we have received several interesting inquiries and requests for further information from classes and have been amending the program appropriately.

We have come to appreciate the huge potential for linking people in a networked environment through compelling educational activities and how simple it is to reach broader audiences with valuable content. Much in the same way our visitors use the (real) museum space as a shared space - a place to extend personal knowledge in a social framework - so the net may well become a similar space for the student - this time bringing the museum right into the classroom. These new environments offer a wealth of opportunities for art educators who may harness these tools over the Internet to impressive ends.

We are at present witness to the Internet expanding at an explosive rate. Hundreds of new art web sites appear daily and while the educator is well versed in selecting the appropriate written online material for their students, they are often perplexed at the wealth of material out there for their students. It is often not clear if the material available to the student is appropriate, or even accurate and teachers are left to their own instincts to find the suitable web sites that enhance the curriculum. Images may be 'borrowed' from dubious sources, possibly cropped or even altered in subtle ways that are indistinguishable on line. Who should be responsible for the authenticity of these images and how in the chaos of the Internet today is this manageable?

One of the important issues rising out of all this chaos is the question of intellectual copyright. Who should be responsible for distributing these images and how can authenticity and accuracy be maintained?

Copyright protects 'original works of authorship' i.e. works that are 'fixed in any tangible medium of expression' such as: plastic arts, paintings, sculpture etc.) musical works, (operatic, popular songs, instrumental) plays, dance and pantomime, movies and multimedia presentations, written works (plays, novels and poetry), and architectural works. Copyright protection starts as soon as the work is created. A work may be copyright protected when it can be recognized as an individual, inspired act and has been translated into something original, creative and tangible, and not copied from another source. However, ideas or facts are not included. This fixed form does not have to be readable by the human eye, as long as the work can be perceived either directly or by a machine or device, such as a computer or projector. In other words, programming and substantive content stored on floppy disks or CDs are 'fixed' as long as the works can be read with the use of a machine.

Copyright protection is limited in time. As a general rule, most countries have adopted a term of protection that starts at the time of the creation of the work and ends 70 years after the death of the author. If these works are to be used in any way by a second party, it must be by specific permission, and may entail a fee. This simple act recognizes the owner of the copyright and the way in which the work is distributed to the public, requiring that their names be indicated on the copies of the work and protects these works from being duplicated incorrectly and without authority.

The Internet does not differ from other media in the concept and application of copyright protection and is in fact, a two-sided coin, While it is the responsibility of content providers such as a museum to adhere to good practice for the authors we represent at our web sites, we would also not welcome our own works being misused by others. To this end, the Israel Museum is at present, looking into a new application in conjunction with a local company to protect images from unauthorized download.

Another interesting discussion arose when, for the first time, we, as museum educators were not actually working from within museum walls, rather having to rely on the piped in digital version of the collections rather than the authentic image. Were we doing justice to the collections? Were we substituting a pale shadow of our collections and confusing the concept of a museum visit by substituting the real with the virtual?

What is not obviously available online to the remote visitors on his or her virtual visit, is the ambiance of an art museum, and of course the experience of enjoying the original art work in the gallery with other visitors. When we see the authentic object with our own eyes, be it in an art gallery, archeological museum or sculpture garden, it is the impact of the original and singular that impresses us and the confidence that there is no duplication. These art works or historical objects also enable us to transcend our own internal continuum, transporting us, for a brief moment, outside of our own microcosmic existence to another place or time.

Is all this totally lost in the digital image over the Internet? The art works

per se, are not the only ingredient of a museum visit. In presenting an exhibition, whether the art works be real or virtual the curator must make the very same decisions in the selection of art works? This is the curators' perspective of an exhibition, an opportunity to offer a contextual presentation of art works. The thematic placing of the art works may outline similarities or contrasts, spotlight trends, styles or artistic periods and in this way serve to promote ideas, or the cultural and social messages that the connected art works represent.

Educators can make use of these thematic presentations, both on line and off so that a visit to an art exhibition becomes a learning opportunity and a vehicle to extend personal knowledge and human experience. It is what the student/visitor is able to take home with him or her after an exhibition visit that is important, and if these concepts are clarified through thematic digital presentations online, then, in spite of the lack of the original, the cultural message is conveyed and the museum educational mandate has been accomplished. Just as a real museum is perceived not only as a space for exhibiting art objects but more of a culture center, a stage for the exchange of ideas via gallery talks or "hands-on" workshop activities, so the virtual environment may be similarly orchestrated for the student in the classroom.

Many of us prefer to visit a museum on our own while others tend to think of the museum visit as an opportunity for family or friends to be doing something pleasurable together. The Museum@school project is addressing this by encouraging students, teachers, and the museum to interact in a shared space.

It is to this end we created the Museum@school project and look forward to developing this exciting new vehicle in the years to come.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()