|

|

Some interactive stories offer participants the ability to assume multiple perspectives of the same event, in turn adding richness and complexity to the narrative. Although interactive environments offer the best medium for multiple perspectives, other media have already experimented with the approach. In Hamlet on the Holodeck, Murray examines multiform stories in media such as the cinema and literature, and how these stories foreshadowed the multiple-perspective stories of interactive media. According to Murray, multiform stories are written or dramatic narratives that present "a single situation or plotline in multiple versions, versions that would be mutually exclusive in our ordinary experience." In well-known movies such as It's a Wonderful Life, Back to the Future, and Groundhog Day, the plots revolve around seeing the outcome of the same stories change through the inclusion of an alternate set of events.

Some interactive stories offer participants the ability to assume multiple perspectives of the same event, in turn adding richness and complexity to the narrative. Although interactive environments offer the best medium for multiple perspectives, other media have already experimented with the approach. In Hamlet on the Holodeck, Murray examines multiform stories in media such as the cinema and literature, and how these stories foreshadowed the multiple-perspective stories of interactive media. According to Murray, multiform stories are written or dramatic narratives that present "a single situation or plotline in multiple versions, versions that would be mutually exclusive in our ordinary experience." In well-known movies such as It's a Wonderful Life, Back to the Future, and Groundhog Day, the plots revolve around seeing the outcome of the same stories change through the inclusion of an alternate set of events.

Interactive stories carry these multiple perspectives further by allowing the user to choose which version to follow or which events to avoid. Non-fictional stories offer interactive storytellers particular challenges when using parallel perspectives, but the model is nonetheless a powerful one to use to increase awareness of the impact of point of view and multiple truths.

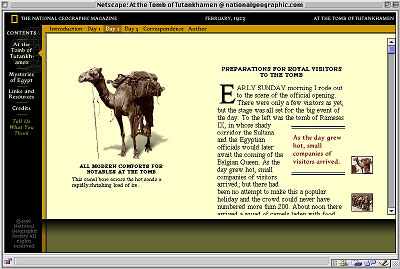

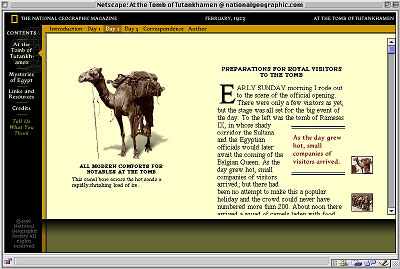

In a Web site called "At the Tomb of Tutankhamen" (http://www.nationalgeographic.com/egypt) we worked with National Geographic to provide multiple perspectives on an event that happened over seventy years ago. The event was the official opening of the tomb of the pharoah Tutankhamen in 1923. National Geographic had sent correspondent Maynard Owen Williams to Egypt to report on the ceremony, and later that year the Magazine published his written account and photographs he took on the scene.

In the interactive revival of this classic story, National Geographic decided to give the user two "sides" of the same story, both of which came, ironically, from Maynard Owen Williams. One perspective of the story was the official account printed in the Magazine. For this side of the story, the article and its corresponding photos were presented as if they had been sent as "live" dispatches from the field. It was an interesting twist to make the printed account more engaging.

But beneath the official story, National Geographic also included an important subplot in the interactive version. The content for this subplot came from letters that Williams sent back to National Geographic's editors as he was working in the field. It reveals interesting insights into Williams' experience unseen in the official story: his disappointment in what he saw in the tomb, his effort to establish the young National Geographic Society as a reputable scientific organization, and his professional conflicts with Lord Carnarvon, the underwriter of Howard Carter's expedition. Through the Web both of these stories are told simultaneously. The user is free to interpret the "real" story for himself.

Immersive spaces

The US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC is one of the world's most compelling educational storyspaces, both because of its subject-matter and because of its structured narrative experience. In the museum's hauntingly appropriate building, the visitor follows a chronological story of the origins, events, and impact of the Holocaust. The experience begins with a slow elevator ride from the ground floor of the museum to the top floor. As the darkened elevator creeps slowly upward, a carefully-timed video clip and chilling first person oral account of what it was like to first encounter the indescribable horrors of the concentration camps plays above the visitors' heads. Combined with the motion of the elevator, the presentation gives visitors the feeling that the elevator is somehow moving them backward through time. The clip describes scenes from 1945, but this is not their final destination. As the ride concludes, visitors disembark into exhibitions detailing life in pre-Nazi Germany. With a 30-second elevator ride, the museum has transported visitors back 70 years in history.

Interstitial experiences such as the one the Holocaust museum handles so masterfully can also find appropriate and effective use on the Web. These often overlooked entry spaces into sites have become useful ingredients for building interest in the online narrative. With attention rates on the Web so low, the first several screens of a site are crucial in "selling" the visitor on the worth of the narrative to follow, just as a film may use a gripping prologue scene to hook the viewer.

Most sites on the Web today dispense with all notions of an entryway, choosing instead to place the user directly in the middle of the action, with the site's top-level sections apparent from the start. Forgoing the entryway is sometimes the correct decision, especially with often-used reference sites. For instance, Yahoo!'s directory of Web sites would be poorly served with such an interstitial section.

Other sites favor a single splash screen, preceding the core site, which begins to set the tone and character of the site before the user actually enters the heart of the site. Such screens become boundary markers that not only help the site establish its voice from the outset, but also serve to separate the site from the rest of the Web. Critics of splash screens argue that their creative impact is not worth the extra time the user must take to download them, and some repeat users find splash screens inhibit their return visits.

Sometimes, however, the impact of an online story can be enhanced by expanding the interstitial experience beyond a single screen in order to capture the user's interest and imagination. Instead of simply hinting at the narrative to follow, these screens can actually become central to the site's story, by distancing the visitor from the outside Web and turning his attention to the story at hand.

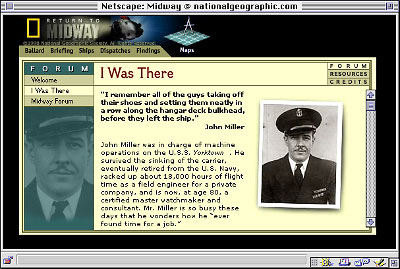

Interstitial spaces can be educational as well as dramatic. In "Return to Midway," we were looking for a way to explain the extreme depth at which Ballard's expedition team would be working to locate the remains of the aircraft carriers. At three miles deep, this expedition was the deepest yet conducted by Ballard. However, very few people could truly comprehend how incredibly deep three miles actually was, since our human sense of scale has no reference by which to understand it. To answer this problem, we introduced an interstitial space into the Web site that would accomplish this feat.

Visitors enter the site at a single splash screen that briefly explains the history and reason behind the expedition. This screen invites them to "dive" down to the ocean floor with Ballard. This "dive down" interstitial experience is in fact only a single scrolling page which reproduces in exact scale the depth at which the expedition was working. At the top, the visitor sees the ocean surface and sky with instructions on diving down. Scrolling down the page, the ocean water darkens as the visitor dives deeper and deeper. Along the way, the visitor meets facts and figures that give the depths understandable meaning: the height of the Empire State Building, and the depth at which the Titanic was found, for example. The actual HTML page is about six feet in length, which is long for any document of text. But by the time user gets to the end of the page, he feels like he has dived down three miles below the ocean. Appropriately, at the bottom of the dive down, the visitor finds the main menu of the Web site, and for the rest of his stay he feels far enough removed from the rest of the Web to focus on the site's story. The interstitial space has connected the visitor to the narrative.

Other interstitial spaces accomplish this effect in different fashions. In "At the Tomb of Tutankhamen," the space draws conventions from cinematic narratives to transport the visitor back in time to 1923. As the visitor enters the site, the space is completely dark, much like the darkened cinema. Then as a mysterious Egyptian chord plays, the site's title fades in and then out again. From the black appears the year - 1923 - and then the location - Luxor, Egypt - to place the user in space and time. These fade, and then appears a more traditional prologue introducing the rest of the site's story. This interstitial has served to move the user in time as well as space.

The spatial quality of Web sites is certainly not limited to the entryway. Some sites use a spatial approach to make the story more engaging. Early efforts of this approach have the user wandering around a three-dimensional museum, moving from exhibit to exhibit, or painting to painting. This approach carries over the conceptual baggage of physical spaces, requiring the visitor to walk hallways or ride elevators to see content as he would have to do if he was visiting the physical museum.

However, three-dimensional immersive experiences can be interwoven with two-dimensional spaces for easier user navigation or even as a surprise experience to make the story more memorable. For example in "At the Tomb of Tutankhamen," most of the site is modeled on the two-dimensional metaphor of the National Geographic Magazine, allowing the user to navigate from "page" to "page." However, when the user follows the author into the burial chamber, a strikingly different navigation approach greets the user. A photo of the tomb's entrance invites the user to "enter" the tomb. Doing so takes the user into a spatial mockup of the tomb's layout. Choosing points of interest in the space brings photos to life, as if the user were standing inside the tomb. At the end of the section, the user is led out of the three-dimensional tomb, and back into two-dimensional space. For the user, the climax of the story is associated with a radical change in navigation.

However, three-dimensional immersive experiences can be interwoven with two-dimensional spaces for easier user navigation or even as a surprise experience to make the story more memorable. For example in "At the Tomb of Tutankhamen," most of the site is modeled on the two-dimensional metaphor of the National Geographic Magazine, allowing the user to navigate from "page" to "page." However, when the user follows the author into the burial chamber, a strikingly different navigation approach greets the user. A photo of the tomb's entrance invites the user to "enter" the tomb. Doing so takes the user into a spatial mockup of the tomb's layout. Choosing points of interest in the space brings photos to life, as if the user were standing inside the tomb. At the end of the section, the user is led out of the three-dimensional tomb, and back into two-dimensional space. For the user, the climax of the story is associated with a radical change in navigation.

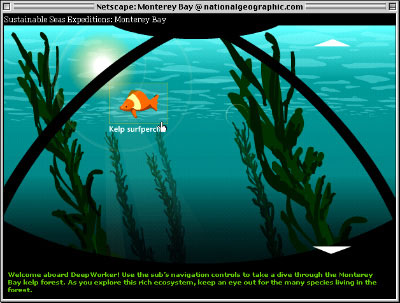

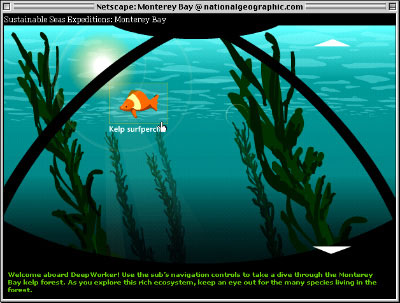

Other sites can package the three-dimensional experience as the "E ticket attraction" of the site. In an upcoming site, National Geographic invites the user to explore the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. The centerpiece of the site is a three-dimensional kelp forest that visitors can dive through using the DeepWorker submarine. As the visitor descends through the kelp forest, he is told the story of the forest's ecosystem. Additionally, the user is able to select fish as they swim by for more information about how they fit into the story of the kelp forest. Even as the marvelous Monterey Bay Aquarium seeks to bring the outside inside, such an experience as the immersive kelp forest take the story of the ocean's ecosystem to the next level by removing the distinctions between inside and outside.

Other sites can package the three-dimensional experience as the "E ticket attraction" of the site. In an upcoming site, National Geographic invites the user to explore the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. The centerpiece of the site is a three-dimensional kelp forest that visitors can dive through using the DeepWorker submarine. As the visitor descends through the kelp forest, he is told the story of the forest's ecosystem. Additionally, the user is able to select fish as they swim by for more information about how they fit into the story of the kelp forest. Even as the marvelous Monterey Bay Aquarium seeks to bring the outside inside, such an experience as the immersive kelp forest take the story of the ocean's ecosystem to the next level by removing the distinctions between inside and outside.

In conclusion, while storytelling on the Web has a rich heritage on which to draw, as an artform it's still very much in its infancy. Just as in the early days of the cinema, when close-ups and dissolves were leading edge innovations, today's Web designers are now discovering new techniques, devices, and conventions for telling stories. Some of the techniques are being used by interactive storytellers, while many others have yet to be discovered. Fortunately, even in its current low-bandwidth incarnation, the interactive story space of the Web is still very much a terra incognita for the next generation of Disneys, Lucases, and Spielbergs.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()