![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Archives & Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto, Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

info @ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search A&MI |

Join

our

Mailing List.

Privacy.

published: April, 2002

Digital Primary Source Materials in the Classroom

Nuala Bennett, and Brenda Trofanenko, University of Illinois - Urbana-Champaign, USA

http://images.library.uiuc.edu/projects/tdc

Abstract

Digital technologies bring museums, libraries, and archives together to enhance learning by providing access to digitized primary and secondary cultural resources along with the more traditional bibliographic materials. At the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the University Library and the College of Education are developing a collaborative program that integrates digital primary source materials into K-12 curriculum and the educational programs of museums and libraries. Teaching with Digital Content—Describing, Finding and Using Digital Cultural Heritage Materials (http://images.library.uiuc.edu/projects/tdc) is a two-year project funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Through this project, we are introducing a broad group of K-12 teachers, museum curators, educators, and librarians to digital cultural heritage materials. Our goal is to provide them with training and professional development activities to enable use of primary source materials in the classroom and in museum and library education programs. In this paper, we will describe the collaborative Teaching with Digital Content project and show how the educators are using on-line materials in their learning environments.

Background

The Teaching with Digital Content project (TDC) project, which started in 2001, built upon previous work undertaken with another project, the Digital Cultural Heritage Community (DCHC) (http://images.library.uiuc.edu/projects/dchc). The DCHC enabled the digitization of materials from East Central Illinois area museums, archives and libraries for 3rd, 4th and 5th grade social science curricula (Bennett & Jones, 2001). This project built upon the concept of a digital community where institutions would contribute content to a database that contained images, text, descriptive information and other multimedia objects to address common themes (Bennett & Sandore, 2001).

The DCHC project aimed to increase the ease with which teachers would utilize these online resources, enabling them to incorporate the new resources in their classroom activities in ways that would be educationally meaningful for their students. We established a framework for the creation of a test database of historical information from area museums, libraries, and archives and tested its viability to meet the curriculum needs of teachers in upper elementary school classrooms in Central Illinois. During the DCHC project, we also sought to develop, document, and disseminate both the processes and products of a model program of cooperation between museums, libraries, and archives.

Several key recommendations resulted from the DCHC project participants (Bennett, Sandore & Pianfetti, 2002). The teachers judged the linking of digitized content to curriculum units and statewide learning standards to be very valuable. The project provided them with an opportunity to match the mandated state learning standards with several classroom activities. The developed database was robust enough to enable very different participant institutions deposit metadata records conforming to the Dublin Core format.

The teachers argued that the quality as opposed to the quantity of resources was important. Educators assigned a high value to the availability of “trustworthy” primary sources via the Web. The time line of the project had not allowed for adequate use and evaluation of digital resources in the classroom. As with many similar projects, the length of time it took to choose artifacts for digitization and the actual digitization took a lot longer than initially anticipated. Finally, the need to increase the ease by which teachers used the images and metadata online in the classroom and for assignments became a significant issue.

To further the DCHC project, and to address specifically the resulting benefits and limitations, we proposed and received new funding from the IMLS to bring together ten Illinois and Connecticut museums and libraries and their digital content with K-12 teachers from four school districts in Illinois. This project, administered by the Digital Imaging and Media Technology Initiative of the University of Illinois Library, would also allow us to work more closely with a larger group of museums, libraries and educators.

Museum, Library and Teacher Partnerships

In the new Teaching with Digital Content project, K-12 teachers from four Illinois school districts (Bloomington Public School District #87; Champaign School District #4; Springfield Public School District #186; and Urbana School District #116) are working together with ten museum and library partners:

- Chicago Public Library Special Collections Library, Chicago, IL (http://www.chipublib.org/digital/lake/jwedept4_2tn.html);

- Early American Museum, Mahomet, IL (http://node-03.advancenet.net/%7Eearly/);

- Illinois Heritage Association, Champaign, IL (http://illinoisheritage.prairienet.org/);

- Illinois State Library, Springfield, IL (http://www.cyberdriveillinois.com/library/isl/isl.html);

- Lakeview Museum of Arts and Sciences, Peoria, IL (http://lakeview-museum.org/);

- Lincoln Home National Historic Site, Springfield, IL (http://www.nps.gov/liho);

- McLean County Museum of History, Bloomington, IL (http://www.mchistory.org/);

- Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, IL (http://www.msichicago.org/);

- Mystic Seaport, Mystic, CT (http://www.mysticseaport.org/);

- UIUC Rare Book and Special Collections Library, Urbana, IL (http://www.library.uiuc.edu/rbx/).

Using an on-line Webboard as the primary means of discussion and communication, the teachers are sharing curricular development and implementation with the museum curators and librarians. Working in conjunction with the College of Education, the teachers have been given guidance on how to develop and engage digital technologies into their knowledge about teaching, teaching about the past and “history,” and are learning how to develop and implement these through their lesson plans. These are traditional “lesson plans,” in that each includes introductory information about the topic of the lesson, the grade level and the curriculum content area such as social studies, economics or language arts.

Within their lesson plans, the teachers have also identified which of the mandated Illinois K-12 Learning Standards they seek to address with their lesson plans. A recent study of the Education Network of Australia emphasized that “good pedagogy approaches” were necessary to shape the use of digital resources and that children’s use of digital technology needed to be guided by its relationship to specific learning goals and integration into specific learning environments (Downes et al, 2000). The Learning Standards are mandated by the Illinois State Board of Education, and Illinois teachers must ensure that lesson plans correspond appropriately. State Goal 16, for example, ensures that students will “understand events, trends, individuals and movements shaping the history of Illinois, the United States and other nations”. Within that Goal, there are more detailed categories. The teachers then outline in their lesson plans the activities that meet the Standards and the procedures that the students follow during the lesson. The TDC project differs from the widespread posting of lesson plans on various Web sites, in that those teachers participating in the TDC project suggest specific ways in which the TDC online database might be used in the development of the lesson.

One 4th Grade teacher developed a lesson plan on “Choosing the Lincoln Statue”, a competition to design a new statue of Abraham Lincoln for outside the Champaign County Courthouse. During that lesson, students would discuss the chronology of events in the life of Abraham Lincoln, use the TDC database to research the years when Lincoln practiced law in Urbana, Champaign County, search the TDC database for images of Lincoln during the targeted years, and finally, create their own designs for the new statue.

Lesson plans cover a wide range of topics; such as African folk tales, the Civil War, the History of Money, and Settling the Midwest. They also cover a wide span of student ages, 3rd grade through 12th grade. Using the Webboard to share the lesson plans with museum curators and librarians, the teachers also provide the museums and libraries with specific requests for cultural heritage objects for their curriculum planning, development and implementation. Similarly, the museum curators and librarians suggest primary source material from their collections that can be digitized for the teachers’ lesson plans. Once artifacts are chosen for digitization, the museum and library participants are developing new metadata which include reference to the Illinois Learning Standards.

Online Database

As discussions develop about the artifacts that would be suitable for the teachers’ lesson plans, the ten participating museums and libraries are simultaneously contributing digitized primary source materials and accompanying metadata in Dublin Core format (http://www.dublincore.org) to an on-line database and search engine. We have made some simple changes to the Dublin Core (DC) field name format used in the database. In particular, we have included fields such as Interpretation, mapped to the DC Description field. (Other fields and their corresponding DC mapping are described in Bennett et al, 2000.) This was due to requests from the teachers for easier identification of field names in the metadata and from discussions among museum and library personnel about how they would like to use the DC for their collections.

As well as the teachers’ lesson plans, the Illinois State Board of Education Learning Standards guided and directed the identification and selection of primary source materials for museum curators, archivists and librarians to include in a digital repository . Discussions among the schoolteachers, museum curators, and librarians identified artifacts to be digitized. Although a teacher might have specifically requested artifacts relating to Abraham Lincoln, the museums and libraries, taking into account State Goal 16, might have images of other “individuals and movements shaping the history of Illinois” and suggest those as being usable in the Lincoln lesson plan.

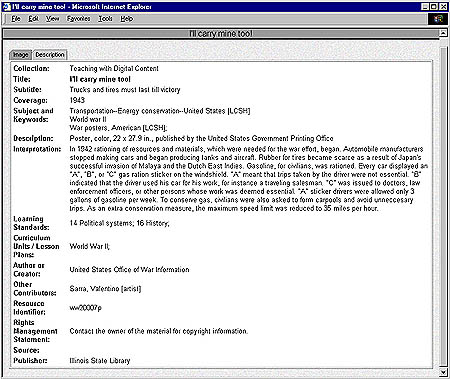

Curators and librarians developed the metadata to correspond to each artifact that would be digitized. The metadata was subsequently formatted in Dublin Core. These artifact images and metadata were then added to the on-line database (http://images.library.uiuc.edu:8081/cgi-bin/htmlclient.exe). The metadata for each artifact image was developed to take into account the different lesson plans and different themes where the image might be used, the different age levels of students and the different requirements of the teachers. For example, one elementary teacher and one high school teacher submitted lesson plans on the two completely different themes of World War II and Women in War (http://images.library.uiuc.edu/projects/tdc/LessonPlans/index.html). The Illinois State Library has a large collection of World War II posters. The participating librarians investigated their poster collection to find some that would fulfill the needs of both teachers and have started digitizing over 100 posters that would help with both lesson plans. In the instance of the “I’ll carry mine too!” poster, the library personnel submitted the image and descriptive metadata to the database following several conversations on the Webboard with both teachers. Figure 1a shows the image of a World War II poster held by the Illinois State Library, and Figure 1b is the metadata corresponding to the poster.

Figure 1a. Poster from the Illinois State Library World War II poster

collection – “I’ll carry mine too!” (http://images.library.uiuc.edu:8081/cgi-bin/htmlview.exe)

Figure 1b. “I’ll carry mine too!” World War II poster descriptive

metadata

Similarly, museum and library partners are digitizing parts of their collections to correspond to other lesson plans. Museums and libraries are assisting teachers by placing the digital objects in their historical contexts. They also identify and help teachers locate and utilize other freely available Web based resources that might be helpful with particular lesson plans. Our experience with the DCHC project was that teachers wanted a trusted source for on-line material to use in the classroom. They do not have the time to research Web resources that would be useful in their lesson plans, but they would be happy to use such resources. Having a trusted group of librarians and museum curators recommend such resources removes that barrier, and the teachers can use other resources in the classroom, or also recommend extra resources to their students. However, the teachers still require much guidance on how to use such resources in the classroom.

Educating the Educators

Besieged by increasing demands for “technological literacy”, teachers are invariably being positioned in an environment where it is essential to appear to be utilizing various technologies. One of the most significant aspects in the contemporary calls for integration of a range of digital technologies into school classrooms points to the “wonders” of computer-mediated learning. New technologies tend to be used in classrooms in ways that are consistent with traditional practices, focusing on goals pertaining to the empirical assessment of student achievement in relation to state learning standards. While teachers in Illinois cannot ignore these standards, the teachers involved in the TDC project are developing lesson plans and activities that are also pedagogically sound and l support student learning rather than being entirely standard directed and driven.

A productive relationship between teachers and museum/library personnel allows teachers to expand their own knowledge base and skills as well as that of their students’

The nature of teaching, the use of digital primary source material, the purposes of the project, and the benefits – and the limits – of technologies in the classroom are all concerns that arise in the various professional development workshops and interactions among and between the teachers, the museum and library individuals, and the project personnel. In presenting practical strategies for effectively engaging with issues about teaching about the past and culture through the use of digital objects, several professional development activities have been planned, instituted, and evaluated, primarily through workshops, summer institutes, and working sessions.

Over the two-year project, the teachers, museum and library participants were introduced to topics specific to teaching with digital content in four workshops. In the first workshop, the teachers were introduced to current research about history education and the tension between knowing what is considered “history” and the past. That the teacher’s own historical understanding will influence the students knowing about history, the past, and the tension between the two directed this initial workshop. Teachers were also introduced to the notion of primary sources and the analysis of primary source material (http://images.library.uiuc.edu/projects/tdc/August2001Workshop.htm).

The second workshop brought together individuals from the cultural heritage institutes and the teachers to discuss how the meanings of objects change through digitized imaging, and the interpretive and educational roles the teachers, museum and library personnel have in student understanding. The teachers discussed the role of the object as a medium for learning in the classroom (http://images.library.uiuc.edu/projects/tdc/January2002Workshop_files/). The third and fourth workshops, which will be held at mid-point through the final year of the project, will bring the teachers together again with the museum curators and educators and librarians to further develop learning activities and to engage with issues concerning digital content, notably how differences in the media of primary sources (i.e. photograph, artifact, written text) influence how students learn about the past and how teachers teach about the past.

Assistance is also provided to the teachers to enable them to integrate the digital cultural heritage materials into their curricula. It is not enough for teachers to hear about the theory; they must also be given hands-on assistance to enable them to use the technology in their classroom. Each teacher participant also partakes in The Moveable Feast program, a one-week summer institute held at several locations throughout Illinois, which is tailored to the needs of utilizing technology in teaching. This project-based technology institute emphasizes ways to integrate technology in conjunction with lesson plans and the Illinois Learning Standards. As well as the teachers, museum educators and librarians can partake in the Moveable Feast program. Participants receive hands-on training in up-to-date software products and productivity tools that they can use in the classroom. Participants also share ideas for curriculum and Illinois Learning Standards integration.

Since the focus of the project is on understanding, developing, and advancing the social context, or “communities of practice” necessary to engage in educational reform (Lave & Wenger, 1991), the aim is not to participate in producing teachers who have already managed to succeed in traditional ways of teaching history and who now wish to succeed in understanding and addressing the new knowledge and issues associated with the educational intent of digital environments. The aim is to identify and describe the collaborative environments conducive to developing technological and educational competence in the teachers, museum and library personnel, all with an aim of improving the educational experiences of Illinois students. By taking a collaborative approach that focuses on the sociocultural aspects each participating institution brings to education, we hope this project may contribute to a better understanding of collective and interactive attainments, rather than limited individual successes.

Collaboration

The success of the Teaching with Digital Content project depends on developing and maintaining a collaborative association among the institutions, the teachers, and the project personnel. Therefore, this project presents numerous pedagogical issues for these individuals. Success depends upon how the pedagogical issues – the differences in the culture of universities, museums and libraries, and schools; the traditional association between museums, libraries, and teachers; and the challenges of educational reform by teachers and museum and library personnel – both bridge the expectations and involvement each individual brings to the project, and promote changes that contribute to student learning.

The purpose of the collaboration is a project that can grow into a learning community (Myers, 1996). While digital technologies figure prominently in this project, social interaction among the participants includes on-line discussions, requests, and in-service events. Reiterative revisions prompt ongoing Web site and curricular development. The term collaboration includes two different meanings: to work jointly and to cooperate. For this project, to work jointly requires that the teachers, the museum and library participants, and the project personnel understand each others’ expectations, contributions, and knowledge, and work together to ensure that individual and collective intents and expectations are realized. The relationships between teachers and museums and libraries have traditionally been linear, where the teachers accept without question what the museum and library have to offer. In this project, each individual is considered a full and equal partner. On-line and face-to-face discussions bring forward issues and questions about utilizing digital cultural objects, what knowledge is available about the object from the institutions, as well as how the exchange of knowledge between the teachers and students (vis-à-vis lesson plans as a base element) will extend student learning framed within state-based standards.

The tensions between the ideological and pragmatic purposes of digital technologies that influence the project’s development, use, and results, which are brought to the project by each individual, prompted the development of a knowledge building community approach (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1993). To foster communication and collaboration, we needed to move beyond cyberspace to ensure continuous opportunities for face-to-face meetings to address such issues as whether artifacts from museums can be digitized without lesson plans from teachers or whether lesson plans can completely direct the digitization of artifacts and metadata development.

This project speaks directly to educational reform, of re-tooling and changing the ways teachers are engaged in alternative forms of education. Such educational reform requires self-direction and interest on the part of teachers. This self-interest in making an impact on how museums and libraries are used, and how the information obtained from each is then translated into the classroom, is by far the dominant pattern of collaboration among the participants. The image of one’s ability to change how students learn, the learning expectations held by the teacher or school community, the museum or library’s plans, and the educational system in which each site is embedded, are significant dimensions at both the individual and collective levels. Acknowledging a consistent and on-going commitment to change may result from engaging in the reform process. Those teachers involved in the project need to understand how their involvement changes the teacher’s role in educational reform. How successful the implementation and evaluation of the project is involves reconsidering the teacher-curator relationship to provide a working environment where museum and library staff achieve a greater degree of involvement in planning educational experiences and higher levels of expertise in working with digital content. As well, we seek to provide opportunities for the development of technological skills, both for the teachers and the museum and library staff.

To cultivate a collaborative relationship between both groups includes ongoing attempts to implement practices and opportunities for participation by members. The challenge for this project is to work with teachers who must acquire new skills and develop new teaching approaches when working with digital materials. Similarly, museum and library staff must develop innovative ways of presenting access to digitized primary source materials. Both groups are faced with changing expectations and involvement in the project. The teachers become cognizant and critical of digitized artifacts, while museum curators and librarians release the historical hold on interpretation to the teacher for the purpose of student engagement and learning.

Using digitized primary source materials involves fundamental shifts in the philosophies, service methods, and pedagogies of museum curators, librarians, and teachers, specific to particular audiences and intents. Throughout the TDC project, we are seeking to test the effectiveness of introducing several critical components in the process of integrating primary source material into K-12 classroom teaching, including 1) the use of innovative visual literacy teaching methods in the classroom, 2) a concentrated technology component linking the use of digital technologies with the creation of electronic curriculum materials based on state Learning Standards, 3) easy access to a database containing digitized primary source materials and their descriptive metadata aggregated from a number of diverse museums and libraries, and finally, 4) support (both technical and human) for consistent communication between schools and the cultural heritage associations.

This project binds learning in a context of responsibility and makes each person a contributor to the development of the project. . Thus, the human context surrounding the learning process is at the forefront. For each participant, the learning environment makes possible individual responsibility for learning development, with support from project participants and awareness of being part of a process leading to greater knowledge about utilizing digital content. Cooperation between the participants is key. The scope and complexity of the individual participant’s learning curve encourages this cooperation, but it is equally necessary to come up with opportunity and techniques that introduce and reinforce knowledge exchange. It is understood that "to be a partner" means to be in a position to intervene with competence in project development, implementation, and evaluation.

The more each participant is aware of the move towards a collaboration, of the necessity to explore changing relationships between museums and libraries, and changing teacher interaction with each, the more effort each individual may be willing to invest.. From this, the teachers and museum and library personnel can move to uncover the possibilities for their own learning and teaching. This rests on their knowledge about educational reform, which requires new considerations in the management of museum and library artifacts in student learning. Conceptions of history through technology involve the teachers and museum/library staffs’ understanding of, knowledge about, and skill development in relation to technologies in their respective field, and their own personal interests and perceived opportunities to develop these interests in relation to TDC project.

Far more critical to the success of the Teaching with Digital Content project appears to be the recognition that social relations frame learning, rather than being derived from it. Each individual will collaborate to refine possibilities for learning. This learning is not limited to either the teachers or the museum and library staff; rather, the learning results when the groups come together to discuss common elements from which to expand.

References

Bennett, N.A., Jones, T. (2001). Building a Web-based Collaborative Database—Does it work? Proceedings, Museums and the Web 2001, Seattle, WA http://www.archimuse.com/mw2001/papers/bennett/bennett.html.

Bennett, N.A., Sandore, B. (2001) Effective Outreach and Collaboration in a Virtual Community: The Illinois Digital Cultural Heritage Community Project, First Monday (http://firstmonday.org/), July 2001.

Bennett, N.A., Sandore, B., Pianfetti, E. (2002). Illinois Digital Cultural Heritage Community - Collaborative Interactions Among Libraries, Museums and Elementary Schools, D-Lib Magazine (http://www.dlib.org/), January 2002, Vol. 8, No. 1.

Bennett, N.A., Sandore, B., Grunden, A.M., Miller, P.L. (2000). Integration of Primary Resource Materials into Elementary School Curricula, Proc. Museums and the Web 2000, Minneapolis, MN, pp. 31-38.

Clift, R.T., Thomas, L., Levin, J., & Larson, A. (1996). Learning in Two Contexts: Field and University Influences on the Role of Telecommunications in Teacher Education, Presentation to the American Educational Research Association.

Downes, T., Arthur, L., Beecher, B., Kemp, L. (2000). Appropriate EdNA Services for Children Eight Years and Younger. Report commissioned by the Education Network Australia On-line Pathways Project, and Education Limited.

Fullan, M. & Stieegelbauer, S. (1991). The new meaning of educational change. New York: Teachers College Press.

Myers, C.B. (1996). University-school collaborations: A need to reconceptualize schools as professional learning communities instead of partnerships. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York.

Hargreaves, A. (1995). Changing teachers, changing times. Teachers' work and culture in the postmodern age. New York: Teachers College Press (Professional Development and Practice Series).

Lave, J., Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Scardamalia, M., Bereiter, C. (1996). Engaging Students in a Knowledge Society. Educational Leadership. Alexandria, Virginia: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Vol. 54, No. 3, November, 6-10.

Oakes, J., Hunter Quartz, K. (1995). Creating New Educational Communities. Ninety-fourth yearbook of the national society for the study of education, Part I. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

Wells, G. et al. (1994). Changing schools from within: Creating communities of inquiries. Toronto, Ontario: OISE Press; Portsmouth, New Hampshire : Heinemann.