![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Archives & Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto, Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

info @ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search A&MI |

Join

our

Mailing List.

Privacy.

published: April, 2002

Representing Asia: Building a Web Site for the Musée Guimet, Paris

Mark Carlson, Musée national des Arts asiatiques–Guimet, Paris, France

Abstract

On January 15, 2001, the National Museum of Asian Arts–Guimet in Paris reopened after an extensive renovation project. The museum's first real Web site accompanied this reopening and went on-line, not coincidentally, on the same day. The renovated museum was dramatically different from the one that had closed its doors nearly five years before, and the Web site was designed to be a reflection of the "new" Musée Guimet.

This paper will examine the experience of designing and building the Web site, in particular, the cultural and political issues involved in representing a European museum which contains one of the world's largest collections of Asian art. Designing an appropriate site meant paying attention to design and content issues, and their possible impact on Asian visitors. As the vision and goals of the museum's director were brought to life, a number of factors played a role, such as the potential audiences of the site, geo-political concerns, and France's relationship to and presence in Southeast and East Asia.

Keywords: Guimet, musée, Asia, Asian arts, Paris, France

History of the Museum

At the writing of this paper, no museum Web site is more than a decade old. However, and not always without attendant complexities, Web sites have come to be the principal representatives of institutions that were, in many cases, founded more than a century ago. As the Musée Guimet recently marked its centenary, it seems appropriate here to give a brief history of the Musée Guimet and its founder, in order to place the design of the Web site into historical context.

Emile Guimet was born in 1836, son of a prominent industrialist from Lyon, and himself a successful manufacturer. When still young, he became passionately interested in the history of religions. He was an avid and frequent traveler. A trip to Egypt in 1865 drew his attention to the moral message of ancient Egyptian religious practices such as the cult of Isis and Osiris. He then decided to deepen his knowledge of the religions of Asia, and traveled to Japan, China and India in 1867. During this trip, he purchased books, paintings and objects–several hundred pieces in all–which would become the basis for the future Musée Guimet (Jarrige, 2000).

In November of 1889, housed in a newly constructed neo-classical building in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower (built the same year), Guimet's collections became available to the public. The institution was not meant to be a museum of Asian arts, but a museum of religions, based on Guimet's original interests. Above all, Guimet wanted the museum to be a "laboratoire d'idées", with much attention paid to research, scholarship, and publication. This emphasis placed the museum's library at the symbolic as well as physical center of the building. The collections of objects which Guimet had amassed illustrating the world's various religions were laid out along iconographic and thematic lines; in addition, a collection of Japanese and Chinese ceramics were presented as examples of craftsmanship and industry. In short, the museum was meant to introduce the West to Asian culture, artisanship, and religious practice. The pedagogic nature of the museum's exhibitions and the lack of a purely art-historical approach meant that masterpieces were not singled out for appreciation, but blended in with similar objects in a given display (Omoto and Macouin, 1993). A pre-World War I view of the museum's Egyptian galleries can be seen in Figure 1 .

Shortly after Guimet's death in 1918, it was decided to change the orientation of the museum. The previous forty years had seen great progress in the field of Asian art studies, and important French archaeological missions in China and Central Asia in the early part of the century had enriched the museum's collections considerably. It was at this point that the Musée Guimet changed its orientation, and became a museum dedicated to Asian art. The transformation was aided by additional French missions in Asia, the transfer of Khmer sculptures to the museum after the closing of the nearby Indochinese Museum in the 1930s and, most importantly, the reorganization of the French state museum structure after the war in 1945. The considerable Asian art holdings of the Louvre were transferred to the Guimet, in exchange for its classical and Egyptian collections. As a result of these consolidations and an active acquisitions policy, the Musée Guimet became one of the largest and most comprehensive collections of Asian art in the world, with more than 50,000 pieces from 17 Asian countries from Afghanistan to Korea.

Figure 1 - Interior view of the Musée

Guimet before 1914

Renovations

In the decades following the 1920s, and particularly after the war, the museum's original floor plan underwent a series of modifications that slowly boxed off the museum's spacious galleries into small and ill-lit rooms. Cheaply-done repairs and renovations left the interiors looking shoddy. Reigning museum design concepts of the 60s and 70s favored very dark rooms in which pieces were lit by spotlights. Finally, the very large holdings of the museum could not be adequately contained in the limited storage reserves, and climate control was almost non-existent. It was clear that a major renovation was required if the museum and its collections were to survive into the 21st century (Eskerdijian, 2001).

In 1996 when the museum closed, its collections were transferred into offsite storage and the entire interior of the museum was gutted and reconstructed. Two additional levels were dug below ground to house the reserves. The "new" Musée Guimet that opened five years later emphasizes natural light wherever possible, and space. The visitor who slowly ascends the museum's floors follows a path that geographically extends roughly from west to east, from India and Pakistan to Japan and Korea. Galleries and floors open onto each other so that connections between various civilizations can be seen more readily. Most importantly, the thematic and iconographic displays from the museum's origins have been supplanted by a spare, uncluttered museology in which the emphasis is on stylistic presentation and historical and geographic continuity. The museum that greets the 21st century is thus considerably different from the one that greeted the 20th century.

Figure 2 - Interior view of the newly-renovated Musée Guimet

The Beginnings of the Web Site

The museum's first Web site appeared only in 1997, when the museum had already been closed for more than a year. It consisted of a few pages, mainly intended to inform the visitor about the work in progress and when the museum would reopen. The site remained untouched for more than three years, and then was dismantled.

When the museum closed for renovations, very few French museums had a Web presence. However, by the time the museum reopened, France had begun to make up for an initially reluctant presence on the Internet, and a comprehensive Web site for the newly refurbished museum was seen as a necessity.

The Director's Vision

The initial direction and scope for the project came from the museum's director, Mr. Jean-François Jarrige. During initial discussions, his vision of the site and what it should accomplish was clear, focused and far-reaching. According to him, the Musée Guimet's Web site should:

- be a second, virtual Guimet museum in size and scope

- be instrumental in attracting and securing new audiences for the museum

- encourage a two-way dialogue between the museum and its public

- help the museum regain its place at the center of Asian studies in Europe

- aid the museum in its privileged role as a place of encounter between East and West

- make the collections of the Guimet available to those visitors who might never come to the museum, particularly those visitors from countries whose works of art are represented in the collections

These criteria, and several others along the same lines, make this a fairly high-level mission statement. Certain issues that are standard fare at other museums, such as building membership or increasing revenues through online sales, did not even make the list. The first point makes it clear that the director wished to build a comprehensive site. Building an audience for the museum was also of crucial importance: the Guimet was, in the years prior to closing, not well-attended, and was very much in the shadow of its bigger sisters, the Louvre, the Musée d'Orsay and the Centre Pompidou. Any remaining loyalties to the museum were further strained by the lengthy renovation period.

The director's vision also makes clear the need to take Asian audiences and sensibilities into consideration. He repeatedly stressed the need to have a site that showed virtual visitors from Asia the care the museum took of its collections and the esteem in which the objects were held. This viewpoint does not spring from any sort of need to be perceived as politically correct, but from a deep lifelong interest in and respect for Asian culture and civilization.

The site, therefore, had to depict the museum accurately, to stimulate attendance by French and European audiences, and to attract the interest and maintain the respect of virtual visitors from Asia and around the world.

Exoticism and its Discontents

Attracting Asian visitors meant that the design of the site needed to avoid representation of Asian art and culture through a European lens, and be devoid of "exoticism". France's presence and activities in China and Southeast Asia over more than three centuries whether cultural, religious or commercial were extremely widespread, important for both sides, and form an significant part of France's history. Unfortunately, too often this long and rich history is reduced to certain impressions or idées reçues, such as the "exotic East". The reasons to avoid such an approach are obvious. In those parts of Asia where Franco-Asian exchange was less present or non-existent (e.g. Korea, Pakistan, India, etc.) such an approach would seem puzzling, while in Southeast Asia it would have run the risk of appearing condescending.

What Color is Asia?

One of the first tasks of the graphic design company retained for the project was to define the graphic charter for the site: colors, typefaces, etc. This immediately produced the first problem: what color is Asia?

The initial design submitted to the museum was awash in various shades of red as background and highlight colors. It was decided that this was a sinocentric view of Asia most likely a reference to colors used in Chinese architecture: wall color, roof tiles, ornamentation, and so on. It also could be linked to the phenomenon of chinoiserie, the passion for Chinese porcelains, artifacts, furniture, etc., which swept the courts of Europe in the late 17th Century. Whatever its sources, red is not an artistic reference for Asia: apart from red laquerware and thangka paintings, red is not a color much seen in Asian art, and since this is main focus of the site, the color needed to be altered.

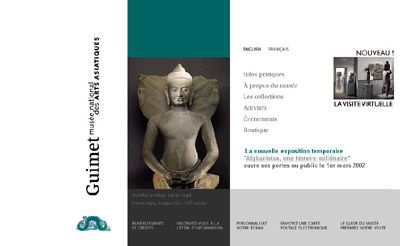

Since the museum makes a great deal of use of natural materials in its displays, especially wood and stone, it was decided to use colors closer to nature: South, Southeast and Eastern Asia contain the widest geographic variations possible, including mountain ranges, jungles, deserts and oceans. By taking this into consideration, the designers finally came up with a much more pleasing and muted palette of greens, blues and grays (see Figure 3 ).

Figure 3

- Home page of www.museeguimet.fr

Room for Thought

It should be pointed out that a large part of the collections of the Musée Guimet consists of pieces—e.g. statues, steles, paintings, etc.—which were/are religious objects, or of objects that had been displayed in a religion setting, such as temples. These pieces were venerated, worshipped, used in ceremonies, and so on. This particularity of the museum's collections and the respect paid to their display was, of course, taken into consideration in the various incarnations of the museum. Over time, however, maintaining such a space for contemplation became more difficult as the interior spaces of the museum became more and more cramped and closed-off.

In their plans for the new interior of the museum, the architects Henri and Bruno Gaudin ensured that there was sufficient space for the works on display. The spacious galleries of the museum give the visitor room to contemplate the objects, to concentrate on them and to think. In addition, the arrangement of the various spaces and volumes and the materials used in the displays do not interfere with the collections, nor do they draw attention to themselves.

It is not possible to reproduce the subtleties and implied meanings of such three-dimensional spaces on a Web page, but the idea that the Web site should be in some way a space for contemplation informed the design process. As a result, pages and templates are not crowded: the palette of colors is attractive but muted. Site navigation headings are placed on the left side of the page in small type. The pages describing the highlights of the collections are fairly unadorned, drawing the user's attention as much as possible to the image and the text describing it.

In attempting to create this contemplative aesthetic, the Guimet site follows the lead of other Asian art museum sites. It was interesting to note that this approach is particularly evident in museums in Asia, much more than anywhere else. Examples of institutions employing a relatively spare interface include the Ho-Am Museum in Seoul (www.hoammuseum.org), the National Museum of Korea (www.museum.go.kr/), the Museum of Oriental Ceramics in Osaka (www.moco.or.jp), and the Kyoto National Museum (www.kyohaku.go.jp).

Geography, Politics and the Collections

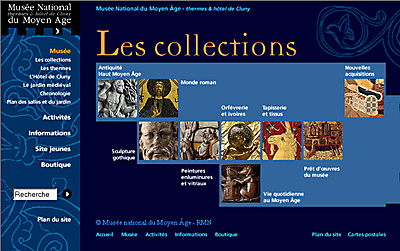

Displaying images from the collections is, obviously, one of the primary goals of many museum Web sites, and this was important for the Musée Guimet as well. The first museum to benefit from the RMN's Web site project was the Cluny Museum, or as it is now known, the Museum of the Middle Ages. As can be seen in Figure 4 , the Cluny's collections are grouped by material and theme, and this method of classification was also offered to the Guimet at the beginning of the architecture design process.

Figure 4 - Collections entry page, Cluny web site

Although this approach is a valid one, and is taken at other Asian art Web sites, it was ultimately set aside in favor of a geographical approach to the collections. As shown in Figure 5 , after clicking on the link "The collections", the visitor is presented with a map of Asia. He or she then clicks on a country or region to view works of art from the chosen area. There were several reasons for this: first, the Guimet's galleries are arranged geographically, and arranging the site in the same way would offer an accurate reflection of the museum. In addition, having to enter via a map offers subliminal information to the visitor: the size and diversity of the Asian continent, the size of the various countries relative to each other, etc. Finally, and most importantly, it was felt that such an approach individualizes the various Asian countries instead of reducing them to the sum of their artistic achievements, and that this approach would have more appeal to Asian visitors to the site.

Figure 5 - Collections entry page, Guimet web site

This approach was not without problems, however—in particular, the very sensitive problem of Tibet. One of the curatorial departments at the museum is called "Nepal-Tibet". The same term is used in the galleries themselves. This is a well-known and useful classification in the world of Asian art museums. However, it presents a problem when it is to be used on the Web. Even though the term is strictly an art-historical one, its use invokes this very sensitive political issue. China, as is well known, considers Tibet to be a province of China–Xizang Province–and not an independent country. Using the term "Nepal-Tibet" could quite possibly alienate a portion of those visitors the site is hoping to attract. There is another term which is in use in certain museums, "Art of the Himalayas", and it was decided that it would be more appropriate to use this alternative term.

However, this did not entirely solve the problem. Access to the collections, as we have seen, is via an interactive map. As the user moves the cursor over a given country or region, the shape of the region becomes black and its name appears. In the case of Nepal-Tibet, even with the change of designation, the rollover would have–quite literally–highlighted the separateness of the region from China. The decision was finally taken to include the shape of Tibet in the rollovers twice, once in the Nepal-Tibet region and again in the outline of China. The shape of China thus displayed will be familiar to Chinese visitors, and in which no Tibetan border is shown, while the area of Tibet is clearly outlined and delineated in the context of the Art of the Himalayas (see Figure 6 ).

Figure 6 - The region of Tibet in two separate contexts

Then there was the matter of the region of the interactive map labeled Central Asia – the part of China known as the Xinjiang-Uygur Autonomous Region, or Chinese Turkestan, and not the collection of countries which is now informally referred to by the same name. The museum's collections include a number of objects from this part of China- primarily paintings and manuscripts brought back from archaeological missions along the Silk Road, and in particular from the cave complex at Dunhuang. Since the museum has two senior curators for China, one for paintings and manuscripts and one for objects, it was decided to provide a separate rollover for Central Asia in order to reflect these two curatorial appointments. However, just as with Tibet, the region of Central Asia appears twice: separately and within the outline of China.

Having read this far, the alert visitor will perhaps notice that, no matter where the cursor is placed on the map of China, Taiwan does not become highlighted. The decision to do so was based on the fact that the map represents the museum's holdings in objects from various countries and regions. Since the museum's holdings do not include any objects from Taiwan, it was decided not to highlight the island with the rest of China.

Asian Art: It's Not Just China

Despite the above discussion, China is not the only country in Asia. The pieces in the Musée Guimet come from a huge, geographically diverse portion of the globe, a region which contains three-fourths of the world's population. The collections, which in addition span five millenia, reflect this diversity. Nevertheless, it is not uncommon for people to equate Asian art only with China and Japan, and usually with a narrow range of types of pieces. A site which played on this perception would be fine for the visitor who is already passionate about Qing imperial ceramics or lacquered boxes, but not necessarily for someone seeking an entry into the vast world that is Asian art.

To emphasize the diversity of art from Asia, the site design includes a certain number of visual clues. For example, the backgrounds of each upper level page (e.g. The Collections, What's Happening, etc.) as well as the home page for each curatorial section contain abstracted images of script in different Asian languages. The language chosen is one from that particular geographic zone.

In addition, the five principal upper-level pages include small black and white images that appear randomly when the user rolls over the various menu items on that page. These images consist of outlines of Asian art objects and symbols, such as ritual bronzes, hands performing various mudrâ (symbolic gestures), masks, statuary from Southeast Asia, etc. These are intended to stimulate the user's interest and curiosity by subtly suggesting the many forms which Asian art takes.

The home page was designed to accomplish the same thing: each time the page is accessed, the central image is one randomly chosen from a series of twenty pictures of objects taken from across the collections. Not only does this give the visitor a sort of "personalized" page each time, but it also gives a broad and multi-faceted glimpse of the museum's collections.

Beyond Design

Up to now, we have mainly discussed the design elements of the site. Of course, design does not keep visitors at a site for long; the content is what they come (and stay) for. The content of the Guimet site was designed with a very large audience in mind, and with several questions in mind. Will it make Asian art accessible? Will it foster learning about Asian art and culture? Will it be interesting to an international audience?

Sections that received particular attention in this regard were the collections and the educational sections. Showing the collections is the most significant part of many museum sites; at the Guimet, it was decided to ask the curators to select their favorite pieces from their respective departments. An approximately 300-word text was written to accompany the picture (and static zoom) of each piece, and glossary links were added to selected words in each text. A total of 120 pieces from every part of the museum were thus made available for the opening of the site, and most of the pieces can be found on display in the museum. In the near future, an interactive zoom functionality will be added: users will be able to zoom in on high-resolution images in great detail.

The educational section was seen as being very important to the site since, as mentioned above, the museum faced the task of winning back its public and creating new audiences as well. School tours and activities are essential in this effort. The site currently offers a list of activities for individuals (workshops, tours, story hours, etc.), as well those for school groups. A page of links allows teachers and students to learn more about selected topics either before or after their visit. A series of in-depth educational dossiers on various aspects of Asian art is in preparation; these will be available for download as PDF files. Finally, a page of games is available for kids; these include "The Emperor's Story", a detailed view of a Chinese scroll painting that helps children learn about an interesting period in Chinese history. Over the past year, the educational section has had an avid following among educators in the French school system, to the point that their comments and wish lists are driving, to some extent, the section's future developments.

The Virtual Tour

Of special importance to the director was a virtual tour, a way to render both the museum and its collections accessible in a more comprehensive manner. A number of options were discussed, and the solution finally chosen was an application from MGI Software. MGI's Zoom Image Server allows high-resolution images—whether in the form of panoramas, 2D zooms, or object movies—to be accessed and easily manipulated with very little download time. It was decided to show the museum by means of a series of 360° panoramas, linked together via hotspots.

A total of eighty panoramas were shot of nearly all the public areas of the museum. They were assembled and linked together by floor. Users may navigate their way through the museum via hotspots in each panorama, or by clicking on an interactive map. In addition—since the panoramas by themselves don't offer additional information about the objects on display—additional hotspots were added to the tour. These are links to text files that offer brief explanations of roughly 150 objects visible in the panoramas, as well as to nearly 40 sound files, that were taken from the museum's audioguides. It is the largest panorama virtual tour of any museum in Europe.

Translations

Since the beginning, the museum's site was planned to be a multilingual one. It is currently—with several minor exceptions—completely available in both French and English. These two languages were the most obvious language choices for the opening of the site. However, in order to communicate with an Asian audience, the site must be translated into at least one Asian language. After some discussion, Chinese was chosen, and a project to create a Chinese site will begin sometime during 2002. The reasons for choosing Chinese were based on the museum's extensive Chinese holdings which account for about half of the total objects in the museum. China also contains the largest number of Internet users of any other country in Asia (more than 40 million, including Taiwan).

Reactions and the Future

After slightly more than a year of being online, the site is slowly becoming known and visited, both in France and abroad. For various technical reasons, precise visitor statistics have up to now been difficult to obtain; however, we do know that the number of unique visitors to the site roughly equals the number of real visitors to the museum: between 5000 and 8000 visitors per week. The site has also proven its ability to retain visitor interest, as a significant percentage of our virtual visitors remain more than twenty minutes, with some staying as long as an hour.

Since the current statistics package is not able to indicate the countries from which the virtual visitors come, an indication of visitor origin comes from e-mail responses. This is not as reliable a method as one would like, as it is impossible to know whether the respondents represent a true cross-section of the site's virtual public. However, mail has been received from around the world, including a number of Asian countries, and comments from this part of the world, with very few exceptions, have been overwhelmingly positive. For those correspondents who have had the opportunity to visit the Guimet, many equate the site and the museum, citing similar attention to visitor needs, accessibility and design appeal.

Future projects include expanding the collections section, increasing the site's educational and multimedia content, and creating virtual tours of the museum's temporary exhibitions. Taken together, these developments should constitute another step towards fulfilling the initiative, begun in 1999, of creating a second, virtual Musée Guimet.

References

Omoto, K. & Macouin, F. (1990). Quand le Japon s'ouvrit au monde. Paris: Gallimard/Réunion des musées nationaux.

Jarrige, J.-F. (2000). The Renovation of the Musée Guimet: Towards a New Understanding of Asian Art in Paris. Arts of Asia 30, 5, 66-70.

Omoto, K. (1993). Emile Guimet et le musée des religions. Beaux Arts, hors série.

Ekserdijian, D. (2001). Personality of the Year: Jean-François Jarrige, Director of the Musée Guimet, Paris. Apollo, December, 2001.