![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Archives & Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto, Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

info @ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search A&MI |

Join

our

Mailing List.

Privacy.

published: April, 2002

Think Globally, Act Locally: The Role of Real Teachers in Community Science Issues

Martin Bazley, Lyndsey Clark, Science Museum, UK, Barbara Bottaro, Karen Elinich, The Franklin Institute Science Museum, USA

Abstract

Science Museums and Science Centers are increasingly seeking more engaging, active ways of involving their audiences. The two partner institutions in this project are working with teachers to get students actively involved with real-world science and technology as preparation for employment and citizenship, whilst building ongoing relationships between the science museums, teachers and community organizations. Last year, US and UK On-line Museum Educators (OMEs) worked with The Franklin Institute Science Museum, Philadelphia and the Science Museum, London to create 'Pieces of Science', a series of on line learning resources, each inspired by a particular museum object. 'Pieces' has been very well received, inspiring the team to consider another ambitious project, aimed at involving students, as well as their teachers.

In this second year of collaboration, the focus has shifted to creating community and issues-based science projects designed to engage students and their teachers in community service, issues-based discussion, and interaction with practicing scientists. The legacy of each project will be a Web site providing related classroom resources alongside a record of the activities and a toolkit to support other teachers in developing similar activities. This paper will focus on presenting lessons learned and suggestions for anyone considering similar projects in the near future, including issues such as how to engender constructive on-line interaction, and what works and what does not in on-line collaboration projects.

Keywords: Teachers, Collaboration, Community, Science, Issues, Educators.

Background

The On-line Museum Educators (OME) project is a partnership between The Franklin Institute Science Museum, Philadelphia, and the Science Museum, London. The project challenges educators to work with the museums, to learn from each other, and to produce online resources. The selected educators have all demonstrated creative use of the Web in teaching. The project and its participants offer a testbed in which informal science education ideas can be exercised. The project has developed and evolved over the past four years with the focus shifting slightly each year. The continually evolving focus keeps the project fresh and innovative and affords the partner museums the opportunity to test new ideas and continually learn from the educators.

Staff from the two museums are supporting the teachers in the development of activities and models. As the teachers create their educational resources, they document their process so that, by the end, there will be a body of data from which staff can draw conclusions and report findings. Likewise, while the teachers are creating resources, they engage in conversation with their international colleagues, ultimately broadening the scope of their thinking and providing an international context for their educational resource creation. Based on the lessons from last year, this process includes creating thematic groupings deliberately mixing UK and US OMEs, and videoconferencing

Current Activity

This year, the aim is to capitalize on our international collaboration by looking at global science issues while also highlighting community and personal action. The project is primarily targeted towards engaging older students (High School in the US and Secondary or Post-16 in the UK) in science through community service, issues-based discussion, and interaction with practicing scientists. We also want to explore and demonstrate how science centres can use the Web to broker a partnership between schools and their communities to address local science-based issues. Some content ideas, like ecology and water chemistry, lend themselves to a strong community investigation/service focus. Others, like health and genetics, lend themselves to a strong focus on debate and individual decision-making. All address the growing international interest in community service as an educational experience and the role of understanding scientific issues in citizenship.

Although we are focusing on older students, the current project participant group includes five teachers of younger students. The chosen project complements current thinking in both the US and UK of ensuring that school students are exposed to the social, ethical, and moral dimensions of science and technology alongside the theoretical subject matter. Rather than thinking of the OMEs and museum staff as a resource production team and the teachers and students involved in the activities as the end users, we are actively encouraging the OMEs this year to involve their students as much as possible in all aspects of the work. OMEs give museum staff an insight into the classroom that only an actively practicing teacher can. By also involving the students, we can learn more about how these ideas work in practice and be sure that all the work has essentially had some form of formative evaluation by the OMEs’ own students.

This year, a key idea under investigation is whether or not similar local science investigations can motivate global thought, communication and discussion.

Themes

We have worked with the OMEs to build three thematic groups: health, energy, and water. Each thematic group is producing a "Community Science Action Guide" - a guide for initiating active science learning around real community issues represents a new contribution to the on-line body of educational content resources. The “Community Science Action Guide” is both an expression of real work and a "toolkit" or "work-pack" to allow others to use or adapt the activities for themselves. It may also prove a source of support and inspiration for other teachers wishing to develop and run similar activities on another topic or theme. There will also be comments on what worked well and what didn’t, based on trialing of some activities and informed feedback on others.

The “Community Science Action Guide” will offer multiple portraits of the role that real teachers can play in community science issues. The OME project participants are becoming role models for other educators. These scenarios will have a lasting value for the on-line educational community, even though the specific activity may have a limited shelf-life. For example, one OME in Florida has challenged her students to organize and implement a detailed water usage analysis in the local hotels. Their community’s economy depends on tourism, and large hotels have a definite impact on the water supply. By learning about the water system, analyzing usage patterns, and making a report to the hotel managers, the students will have embraced standards-based science content in a practical, real-world context. The on-line guide will document their investigation, demonstrating the steps that other educators could follow with their own classes. Their teacher has brokered relationships between them and a powerful community testbed: senior citizens.

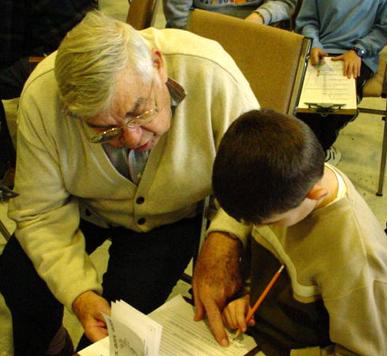

Fig. 1: Young scientists in Ohio are learning about the science of aging

Roles of the On-Line Museum Educators

There are many measures of success for projects like this. Ideally, the OME and her students will establish long-term involvement with key community science stakeholders. For example, scientists and engineers at the local water processing facility will begin to trust that she is capable and reliable, inviting her to return for future projects with other classes. Since the sixteen participants are conducting sixteen different local science initiatives, we may quite likely observe sixteen different roles. Certainly, we will see sixteen distinct portraits. However, the different roles will most likely be categorical. Indeed, we are already detecting patterns that suggest that the roles the OMEs play as local science advocates are perhaps variations on just three profiles: activists, brokers, and consultants.

In the example above, the OME is playing the role of an activist. She and her students detected a latent issue and, by investigating it, are bringing it to the forefront, calling public attention to it. In the field they ask questions, make observations, and record data. Later, in the classroom, they will compare and aggregate their collective data.

Fig. 2: The students act as field researchers

Other OMEs are acting as brokers between their students and local scientists or other interested parties. By “making introductions,” they are brokering new relationships and bridging sub-groups within their community. In this role, they are less narrowly focused on a single issue and are more attentive to the relationships.

By positioning their students as “local experts” on a topic or issue, some OMEs are actually playing the role of consultants, inviting multiple stakeholders to use the students and their research for the greater good.

These three profiles are preliminary categories and may need to be refined as the project work progresses. They are based upon early observations of role-playing and may change as the OMEs grow more comfortable with their activity.

Preparing the Students

Fig. 3: Simulating aging: reading

Before introducing the young research scientists to the residents of a local senior center, the OME had her students visit various “simulation centers” in the classroom for activities that prepared them to think about the issues of aging. Here, a student attempts to read letters while wearing glasses that have been smeared to simulate a slight blurring of vision.

Fig. 4: Simulating aging: loss of dexterity

At this “simulation center,” the students wear rubber gloves to simulate decreased dexterity. They then attempt to complete ordinary tasks like tying shoelaces.

Collaboration Spark

The desire of The Franklin Institute and the Science Museum, London, to work on this project together and to try to capitalize on our international collaboration rose out of our experience of last year's OME project 'Pieces of Science'. While producing the Pieces Web sites, the OMEs worked on their own individual products and interacted with each other in an organic way, sometimes sharing technical experiences, sometimes content ideas, other times experience of working with particular age groups. We believe that these interactions added both to the experience of the teachers working as OMEs and also to the extremely high standard of the Web resources produced. One of last year's OMEs wrote in her online journal:

I believe that we have produced some meaningful classroom content. However, if we are to be pioneers I don't think we can ever sit back and be content to stay in the same place. If the project should continue for another year I would like to see us delve more into the concept of collaboration...what worked in the past and what didn't...and build from our observations.

Choosing Themes and Topics

As we moved the OME project on, we thought hard about what type of work and science topics could be enriched the most by collaboration between UK and US educators.

The idea and motivation to concentrate on how global science issues can be understood and subsequently tackled in a local community context had already been proposed, and we felt that any resource produced by any individual educator could only be enhanced and enriched by the experience of discussing the production process with others from as diverse a range of local communities as possible. There is already great diversity within both the US and UK groups as both groups are geographically spread throughout their respective countries and in rural as well as urban areas. However, sharing between two countries with completely different education systems and, despite a common language, very different cultures would, we hoped, broaden the minds and challenge the thinking of the educators still further regarding tackling global science issues in their own backyard.

Structuring the OMEs

To further develop this broadening of thought, we decided to be more formal with the nature of the collaboration between individual OMEs than we were on 'Pieces of Science'. We decided that on the Community Science Action Guides, although all OMEs would be working on issues in their own community, they should also be required to work with other OMEs from across their own country and engage in conversation with their international colleagues. To encourage the mixing of UK and US OMEs and to ensure that each theme was considered for a whole range of ages of students, we created thematic groupings directly from the outset. We worked flexibly to ensure that all OMEs were able to choose their preferred topic but that each group had at least one representative from each country and at least one teacher of younger students.

At this early stage it is not clear to us whether this model will work as well as simply leaving the OMEs to form natural alliances, as in last year's 'Pieces of Science' project. However, just because it is proving more difficult does not necessarily mean it will ultimately prove to be either more or less rewarding. The results and final conclusions can only be drawn after the resources are completed and the museums and OMEs themselves have had time to reflect on the experience. We certainly have evidence that at least one group has had a number of interesting discussions about the differences between the education systems in the US and UK and has debated the best way in which to reach the largest audience with the technology available.

Getting Started

The ten US OMEs began the project by meeting at The Franklin Institute Science Museum in Philadelphia in August, 2001. The OMEs, Franklin staff and a representative of the Science Museum in London spent a couple of days brainstorming ideas and sharing experiences, while also spending time in the evenings getting to know each other. The weekend mainly provided an opportunity for the group to meet and bond and form working relationships that they could take with them into the online environment, but also allowed us to explore the idea of community science issues and to brainstorm topics as a group. It seemed from that meeting that the resources the educators wanted to produce would fit into three broad thematic groups; energy, water, and health.

Participants expressed opinions that the face-to-face portion of the project was vital.

The face-to-face meeting in August gave the US participants a chance to come to an agreement on a topic and a plan of action. The UK participants didn't have the chance to meet or discuss anything with us. For me, having the chance to meet and come to an agreement initially was invaluable. The give and take of brainstorming was best done face to face.

I think the initial face-to-face is probably crucial to really good collaboration, but if that's not possible then structured guidelines and lots of up-front structure planning by the institutions.

Due to differences in the school calendars in the UK and US and also uncertainties over the funding of the UK chapter, it was not possible to run the UK weekend at the same time. The UK gathering did not in fact take place until late October: 11 weeks after the US gathering. Although this situation was never deemed ideal, it may well prove to have had more of a detrimental effect on the collaboration than we realized at the time. It is clear from the comments above that the US OMEs placed great store by the working groups they had established over the weekend they spent in Philadelphia. Also, as the US OMEs slightly outnumbered the UK OMEs, we were conscious from this stage that it might prove difficult for the UK OMEs to join the groups that had already been established. During the weekend in Philadelphia, we were in the difficult situation of having to stress to the US OMEs that they should be open to the idea of any number of new UK members joining their group ,and also to the chance that perhaps none of the UK OMEs would join their particular group. This left a great many unanswered questions hanging in the weeks between the US and UK meetings.

When funding was confirmed and UK teachers returned from their summer break, the six UK OMEs had their gathering at the Science Museum in London. They were given the three broad themes chosen by the US OMEs to brainstorm around and came up with ideas of their own that were distinct from the US ideas but also fitted into the three themes. This resulted in our eventual current situation where we have three groups working on the topics; each with different proportions of UK and US OMEs.

The idea was for the 'thematic groups' to communicate online, discussing how they can construct resources that are both individual and yet complementary. Each group has at least one teacher of younger children, and the OMEs were keen that the resources for older students should build upon those produced for younger children. Within each group they wanted to produce individual resources for their own classes, but overall, the aim is for three spiraling sets of resources covering each topic area at beginner, intermediate, and advanced level. An on-line workplace was set up on the Franklin's server, with links to an e-mail list and pictures of each OME with e-mail address. Each thematic group was also given a page for a group e-mail list for posting any important documents. By spring term, only the water group had taken up the offer of an individual e-mail list. However, there does not seem to be much correlation between whether or not the group used an e-mail list and the feelings of the group members as to how successful the collaboration is proving.

For example, these three comments are from participants in the Water group who did opt to use a group email list.

The lack of active participation via e-mail within our group is very frustrating for me. Without better communication I'm afraid that the projects won't fit together very well.

Our communication since Philadelphia has been direct and clear. We've been communicating by e-mail off list for details and on list for the broader plans. We've had trouble with feedback from our UK counterparts. I believe that is from the lack of early communication; i.e. the face-to-face preplanning and ironing out of details.

I've been using this time to gather resources for the project. Neither [another OME] nor I have e-mailed the group much. I feel that at this stage we just need to develop our resources, based on the broader picture of the group project, making sure we are not repeating ourselves. I've shared my project outline and read through the outlines that have been posted by the others. I think the main collaboration will come when we start to write the Web pages. For instance, making sure the format is similar/same. I'm getting the feeling that the collaboration side of things is an issue? But, providing the final site can be used in the UK and US, then we have a collaborative project. Though someone will need to sift through the sites and make links from both the US and UK national curriculum standards.

These next two comments are from participants in the energy and health groups who did not opt to use a group e-mail list.

To be honest I haven't made much use of the email forum. I expect that this will come into its own later on as people share ideas while developing their work further.

During the fall semester, the members of the energy group collaborated a great deal to get a common focus. A general structure was decided for future workflow and I had a good sense of what I was supposed to create for the project. In terms of collaboration via e-mail, it is often difficult to decipher what other group members are intending to do in the future. After all, text-based descriptions of what will be created are often much different than what is actually created as the final product. I hope that as things move forward, our group will be able to upload more graphics, animations and video. Working with the other group members has made the energy topic much more interesting, because we can bounce ideas off each other and talk about what actually works in the classroom.

The diversity of these comments suggests that the adoption of an established e-mail list is not a factor in the degree of communication that is occurring within the groups.

The Future

We intend to gather the participant groups again this Spring for meetings at The Franklin Institute and the Science Museum, London. We would like to schedule these meetings for the same weekend and make use of videoconferencing to allow the groups to share their thoughts and ideas. We may even be able to schedule videoconference slots for each thematic group. We have only used the medium of videoconferencing between the UK and US twice before;. The first occasion was during 'Pieces of Science', when we allowed the UK and US groups to 'meet' by videoconference at their second workshop weekends. The large numbers involved on that occasion meant the experience was little more than a fun experience, but all enjoyed putting names to faces and finally seeing those they had been corresponding with for months. The second time we used videoconferencing was at the start of this year's project when due to unavoidable circumstances, no member of US staff was able to attend the UK gathering. Instead we had a brief videoconference with the US staff in order to make the concept of US colleagues seem more real and also to allow the US staff to welcome our new OMEs to the project. The UK OMEs certainly appreciated this chance to put faces to names and are keen to make further use of the medium of videoconferencing at our second workshop weekend.

Freedom or Structure?

From its inception, the OME program has resisted the urge to impose behavioral guidelines, structures and rules. Indeed, the urge has been strong! The participants themselves have sometimes expressed a strong desire to be told exactly how to behave. Over the years, several OMEs have left the program, frustrated by lack of prescriptions for their behavior. However, the OME program is about observing when, where and how communication happens organically. As informal science institutions, we want to learn, by observing the OMEs, how teachers are naturally engaged. The challenge becomes a balance between giving the participants enough structure to be productive while still giving them freedom to be innovative and instructive to our thinking.

Many of this year's OMEs, especially but not exclusively the new members of the programme, probably feel this year that they are spending more time second-guessing what it is the two institutions want and expect from them. If we were to satisfy their hunger for explicit behavioral expectations, then the programme would become less interesting.

There seems to be a deep-seated feeling that the two institutions have very definite ideas of how the OMEs should work and what they should produce, and that we're just not telling them! In fact, the truth is that we want the OMEs to show us how they prefer to work and what they can produce when given free reign to express their creativity and years of teaching experience.

If we were interested entirely in the end product and legacy of each year's OME project, then perhaps it would be incumbent on us to brief the OMEs in such a way as to allow them freedom whilst at the same time specifying closely what we want them to achieve. But the nature of the project is such that we are not solely interested in the end product. Although delivering quality Web resources to our audiences is a consideration, as institutions we are involved in this project to learn from the OMEs. If a particular group does not gel or collaborate "well", it is not an indication of failure of a particular year's project. Indeed, just as in science, negative results are just as valid and useful to the learning process as positive ones.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Unisys Corporation

for its generous support of the On-line Museum Educators program. In particular,

Camille Sciortino and David Curry have been amazing champions of the collaborative

programs described in this paper. The lessons learned and shared here

are made possible by their visionary support for educational programs

at The Franklin Institute and the Science Museum, London.