![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Archives & Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto, Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

info @ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search A&MI |

Join

our

Mailing List.

Privacy.

published: April, 2002

The Design and Development of an Online Exhibition for Heritage Information Awareness

Leong Chee Khoon, Chennupati K. Ramaiah and Schubert Foo, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Abstract

The Internet is a communication channel where ideas and information may be freely and easily shared and communicated among members of diverse communities around the world. By combining the capabilities of latest computers, communication and multimedia technologies, web-base multimedia systems can be developed and delivered through Internet to the distributed users around the globe. Web-based multimedia systems provide an exciting means and communication channel for information access and sharing throughout the world. These systems have immense potential in public education, stimulating the learning process by exploring and doing, and by bringing children out of their school compound on trips around the world with just a few clicks. In this study, a web-based multimedia exhibition “Colours of the Wind” was designed and developed based on an existing exhibition that took the original form of static physical displays. The exhibition is part of a series of National Education exhibitions put together by the National Archives of Singapore to promote heritage information awareness among school children. As part of the design, a requirements gathering study was carried out with 77 university students to determine the users’ requirements in terms of their computer and web experience, content expectations of online exhibition and their prior exposure to these systems. Based on these user requirements, a prototype of an online exhibition system was developed which was subsequently evaluated to assess the prototype and to elicit gaps in the design. In the evaluation with 30 students from the same pool form whom requirements were gathered, it was found that the online exhibition was well received by the surveyed community. The respondents were of the opinion that it has satisfied most of their requirements of an online exhibition apart from a search engine. They also felt that online exhibitions were the most flexible mode of delivering heritage information to inculcate awareness among the school children and public, particularly so, in the context of Singapore, because Singapore has one of highest percentages of Internet users of any country in the world.

Keywords: Online exhibition systems, Singapore Heritage information, Requirements gathering; Evaluation techniques

Introduction

In this digital era, technological advances are rapidly changing the environment in which we live. The impact of technology can be felt in many areas, one of which is heritage information delivery. Today, a large percentage of children grow up in cities around the world, where old and culturally significant architectural structures often have to give way to modern buildings due to land scarcity. The loss of such heritage icons and reduced interaction between children and their parents who spend increasingly long hours at work, result in many school-children not being well informed of the historical richness of the ancestors in their society. This is quite unfortunate, because the way leading to nationhood for many countries is often paved with interesting and noteworthy events. Such events will form an important part of a country’s heritage. This information has to be passed to school children, so that they can better understand the efforts and sacrifices of the people who build the nation, understand the cultural diversity in modern society, and contribute productively to foster unity.

This is where heritage exhibitions enter into the picture. The National Archives of Singapore collects, manages and preserves historical records, and also promotes public interest in heritage through traveling exhibitions, publications and IT-based projects. It has originally developed a series of exhibitions of differing themes as part of the Singapore’s government larger National Education Initiative to promote cultural heritage information awareness among school children and the general public. Such awareness services took the form of static information panels, multimedia kiosks, audio narratives and videocassettes. However, such physical exhibitions are limited in the demographic reach of their target audience. They are also open to the public to access only at certain times of the day. And, since most of the information is presented in physical form, teacher and student visitors find it difficult to customize the materials for their teaching and learning purposes.

Online exhibitions offer a practical and cost-effective solution to the above problems. They are no longer limited to time, distance and space. Students from the nation and all around the world can view the exhibitions remotely both from their homes and schools any time. As the contents in the online exhibitions are in digital form, new materials can be added quickly and existing materials can be updated easily. This dramatically reduces the lead-time and eliminates costly physical space required to display an exhibition (Kassay, 1995; Spadaccini, 2000 and Thomas, 1991). Teachers can easily download the digital materials for integrating into their teaching syllabi. Students can also learn to gather online information, organize it, create some meaning to it, reach insight, and present their findings online to their teachers (Boily, 2000 and Sumption, 2001).

In this project, a prototype online exhibition of a physical exhibition “Colours In The Wind: Old Hill Street Police Station In Retrospect” was developed. This exhibition celebrates the rich history of the Old Hill Street Police Station, a former police barracks which has been converted into the Ministry of Information and The Arts (MITA) building, Singapore.

Aim and Objectives

The aim of this project is to develop an online exhibition for promoting cultural awareness among Singaporeans, and also to study various Internet and multimedia technologies required to build online exhibitions. The objectives of this study are:

- To elicit users’ and information requirements of an online exhibition

- To develop an online exhibition for promoting cultural heritage awareness

- To evaluate and identify the gaps in the design, and

- To find out the impact of online exhibitions on promoting cultural heritage awareness

Background

Prior to designing the online exhibition, we undertook a comprehensive study of existing online exhibitions around the world to examine aspects of their content, presentation, navigational structure, implementation issues, etc. A number of most important sites are described briefly below:

American History Documents (http://www.indiana.edu/~liblilly/history/history.html) is an online exhibition that showcases some of the most important documents in American heritage, e.g. the Declaration of Independence. Each document is shown as a thumbnail image (192“300 pixels) which can be zoomed to 500“780 pixels, together with a short descriptive paragraph. A link is also provided to the full text of the document.

Asian Civilisations Museum (http://www.woof.com.sg/acm.htm) was hosted on an online television station (http://www.woof.com.sg) between February and May 2001. It showcases Chinese culture and heritage in architecture, history, symbolism, religion and ceramics. These are presented via narrative videos (MPEG-4 video with MP3 audio) of the curators, who provide brief introductions to each subject area.

Exploring Africa: An Exhibit of Maps and Travel Narratives (http://www.sc.edu/library/ spcoll/sccoll/africa/africa.html) is an online exhibition on the early history of the African continent. The information is presented through the maps and travel narratives of the Europeans who traveled extensively throughout Africa from the late fifteenth century to the late nineteenth century.

Harlem, 1900-1940: An African American Community (http://www.si.umich.edu/ CHICO/Harlem/) describes the cultural heritage of the African American community. The images on the site may be zoomed from 249“141 pixels to 429“271 pixels. Teachers are provided with online information on the objectives of each sub-exhibit, instructional strategies, photograph interpretation and guidelines on oral history. A search engine is also provided to find the related materials in the New York Public Library.

SCRAN (Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network, http://www.scran.ac.uk) is an online multimedia resource base for Scottish history and culture. It provides carefully designed educational resources, e.g. resource packs with instructions to teachers. SCRAN resources range from static content (text and pictures) to multimedia (audio and video in Apple QuickTime), however, free access to these is limited to Scottish schools and companies only.

Methodology

Fourth generation techniques were utilized for the development of the exhibition. Such a techniques are characterized by the use of widely available graphical development tools to save development time by abstracting the design problem at a higher level (Dix, 1998; Ghezzi, 1991). Through this, the authors were able to concentrate more on the design and functionality aspects. In this case, Dreamweaver 4.0, a web editor was used for prototyping and implementing the online exhibition system. Because Dreamweaver can be used for both the purposes, one can save software resources, design time and manpower. Above all, it is an internationally used, industry standard tool for web design.

Although there are many evaluation techniques, only five important techniques were considered for use in this project.

- Surveys based on questionnaires and interviews are channels through

which the user can communicate his or her opinions passively (e.g. questionnaires)

or actively (e.g. interviews) to the system designer.

- In the observation of task performance technique, users are encouraged

to be verbose on their actions and problems faced, which will be noted

by remote observers for subsequent analysis.

- Activity logging makes use of manual or automatic recording of the

users’ actions (e.g. video-taping), which are then examined for

possible design problems.

- Heuristic evaluation is the systematic inspection of a user interface

design, based on formally recognised system usability principles.

- Co-operative evaluation involves the user discussing with the evaluator on system interface problems encountered during usage.

The evaluation technique chosen was a combination of co-operative evaluation, together with questionnaire-based surveys. This combination offers the best compromise in terms of resource and time requirements, and the reduction of biases in the final results due to the Hawthorne effect, which causes people being watched to act in a different way because of the presence of the observer (Faulkner, 1998).

Requirements Gathering

A survey was carried out to determine the user requirements of an online exhibition system for heritage information dissemination. A total of 77 respondents took part in the requirements gathering process. These respondents were postgraduate students mainly in their mid- to late-20s, with equal proportions of males and females. Most of them were familiar with the web and were regularly using computers, so they were familiar with basic computer operations and graphical user interfaces. This was very important because the web is predominantly a point-and-click graphical interface, especially in the case of a browser intensive application such as an online exhibition. About 96% of them own a computer at home with web access, which allowed us in testing the effectiveness and efficiency of content delivery, especially in the case of bandwidth-hungry applications such as digital video streamed across public networks (e.g. the Internet).

The IBM-PC was the most widely used type of computer (96%), with most of the respondents (97%) using Windows operating systems. These findings were major influences in the decision to develop the online exhibition on the PC platform. The most common monitor screen sizes used by the respondents were the 15” CRT (39%) and the 12.1” LCD (30%). These screens are capable of displaying images up to 800“600 pixels resolution. Surprisingly, 15% of the respondents were still using 14” CRT monitors, therefore the screen resolution selected for development was 800“600 pixels, to cover the widest possible user base. Although 71% of the users had 56 kbps modems, about 7% of the respondents were still using 33.6 kbps modems. Therefore, streaming video and audio are provided at the lowest possible file-sizes to reach as many viewers as possible.

The majority (79%) of the respondents surfed the web daily, so most of them were familiar with the use of web browsers. Hence, a basic help system was deemed good enough for these users and a detailed help system is not required. During their interaction with the system, about half of the respondents expected to see something on the screen within 11-30 seconds of the initial click, which mean that the most efficient compression techniques must be used to deliver digital audio and video, with reasonable clarity while playing back. Internet Explorer was the most widely used browser (83%), followed by Netscape (17%). This necessitated the need for cross-browser compatibility through careful coding of DHTML elements so that the system will reach out to most of the users.

Almost half of the respondents (50%) preferred textual sites with moderate interactivity, while 34% supported highly interactive sites, and the remainder liked text-based sites. A decision was thus taken to incorporate interactivity in the form of DHTML, Java applets and digital audio and video, but exclude complex animations such as Flash and Shockwave. The pervasiveness of Shockwave technology can be observed in the high proportion of users familiar with it (82%). Respondents, especially those with high-bandwidth Internet connections, felt that the interactivity and entertainment value of Shockwave elements were worthwhile in spite of long download times. For this, over half of the respondents (55%) were willing to download the Shockwave browser plug-in, however, 27% found that downloading the plug-in is troublesome.

|

|

Text |

Pictures |

Sound |

Video |

Animation |

Others |

Number |

23 |

33 |

18 |

19 |

19 |

2 |

|

Percentage |

68% |

97% |

53% |

56% |

56% |

4% |

Table 1: Media preference by the respondents

Of the respondents, more than half (56%) of them had not visited any online exhibitions before. The respondents who had visited online exhibitions before (44% of them) reported that they were seeing mainly pictures (97%), videos and animation (56%) at the sites. Other media observed were maps, layout plans, diagrams and virtual reality scenes. The most common form of online exhibitions seen by these respondents were art galleries on the web, in which static images were seen more often than animations, audio and video clips. Images were considered to be most important form by the respondents (83%), followed by video (70%), and then text and audio (69%). Animation was felt to be slightly less important (60%), while a small percentage (4%) of the respondents would also like to see online help, zoom features and interactive media.

The majority of the respondents (59%) preferred brief abstracts with links for more detailed information, whereas 38% liked only brief abstracts and 3% also expressed the need for elaborated text. This is consistent with the basic design philosophy of web information systems, which is to cut down the amount of information presented on each page for better reading. About three-quarters of the respondents indicated that there is a need for text transcripts to accompany the audio and video clips. Of these, English was the most preferred language (86%), while 12% would like to have multi-lingual transcripts.

A large proportion of respondents (89%) indicated that important historic events should be accompanied with video clips for better understanding of the events. Video clips of moderate duration (between 2 to 5 minutes) were considered appropriate to them. About 56% of the respondents indicated that they would rather see animations than video clips, so that it would help them to quickly display the movie file on the web. Nearly 72% preferred Shockwave animations, followed by animated GIFs (51%), AVI animations (49%), Java applets (42%) and DHTML animations (23%). This clearly shows that the majority of the users want to see shorter video clips of all the important events, but they are quite flexible about the video form or format. Depending upon the context, the video format can vary from animated GIF to digital movie so that downloading time will be faster.

A larger proportion (87%) of the respondents agreed that online exhibitions have considerable educational value; however, 13% considered otherwise. About 78% of the respondents expressed interest in getting more information from archival organisations, so these exhibitions may be provided links to other sources for getting more information. The most popular archival items (80%) that the respondents were interested in were photographs, particularly on historic sites, followed by audio/video recordings and maps/charts (77%), public records (67%) and oral history (57%). This clearly shows that the respondents were not so keen on textual information, but more interested in other media resources. This means multimedia with minimum textual information was popular, but links for additional information should be provided.

Most of the respondents (94%) felt the need for a good search engine for effectively retrieving the information, online help, and selective dissemination of information (SDI) through e-mail. Content accuracy was vital, together with quizzes, tutorials and games to bring the educational message across to the school children. Site personalisation or customisation was also suggested by some of the respondents. A few also felt that different information formats were needed to cater to the different modem download speeds of users. Free access to all the archived materials on a topic and links to other relevant materials would help them in getting the complete information. There were also suggestions for more advanced user interfaces and systems to cater to visually impaired users, virtual reality (VR) and video on demand (VOD) applications for advanced users.

Design and Development of the Prototype Online Exhibition System

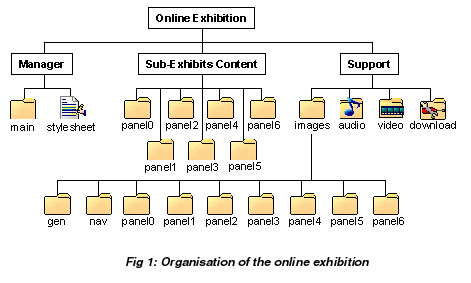

The Colours In The Wind online exhibition was developed with three major components: the “Manager”, “Sub-Exhibits Content” and “Support” components as shown in Figure 1. The “Manager” component consists of a “main” directory that contains the administrative pages, and a global stylesheet. The administrative pages comprise of an “About” page that describes the online exhibition in general, a “Site Map” page that briefly explains the contents of each sub-exhibit, a set of “Help” pages, a “Search” page and a “Feedback” page. Links to these pages are provided through a horizontal navigation bar in a title frame at the top of each page, so that they can be reached from anywhere within the online exhibition. There is also a pull-down selection list of menu options, which are used to select each sub-exhibit for browsing.

The “Sub-Exhibits Content” component contains the pages for each of the twelve sub-exhibits, organised into seven directories. The “Support” component consists of an “audio” directory that contains the oral interview sound clips, a “video” directory that holds the video clips, and an “images” directory that contains all the pictures used in the online exhibition. The “images” directory is further divided into sub-directories, each one containing the images used in each sub-exhibit, with a “gen” sub-directory to hold the images used by the “Manager” component (e.g. images used in the “Help” pages), and a “nav” sub-directory to store the navigation button images. In addition, there is a “download” directory that contains the Netscape plug-in for the Windows Media Player; this plug-in can be downloaded by Netscape users to view the Windows Media audio and video clips used in the online exhibition.

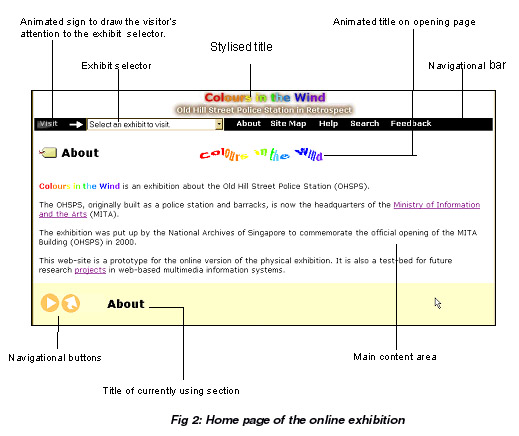

Figure 2 shows the home page of the online exhibition. All the pages in the site share the same general formatting using cascading stylesheets. An animated flashing “Visit” label at the top left corner of the screen draws the visitor’s attention to the exhibit selector. The exhibit selector was implemented using a pull-down menu with automatic page re-direction, instead of a left-hand frame with links, because some of the sub-exhibit titles were rather long. This helped to save screen space and made the look less cluttered, to reduce the visitor’s cognitive overload.

Each page is divided into three horizontal sections (frames). The top navigation bar holds commonly accessed pages (e.g. the “Help” pages), which can be clicked from any page since the navigation bar is located in the fixed top horizontal frame. The large middle section is the content area that holds the text and multimedia elements used in the online exhibition. The bottom section of the page contains navigation buttons and the title of the currently using section. At the bottom left corner of each page, there is a navigational bar with three navigation buttons. These are the standard “Previous”, the “Next”, and the “Back” buttons used in all the web designs. The “Back” button brings the user back to the last visited page, which is similar to the function of the “Back” button provided by the browser.

To reach a sub-exhibit quickly, a pull-down menu is provided at the top left-hand corner of each page in the online exhibition. This pull-down menu contains links to the starting page of each sub-exhibit. On the right of the pull-down menu, there is a horizontal navigation bar containing links to the “About” page, the “Site Map” page, the “Help” page, the “Search” page and the “Feedback” page.

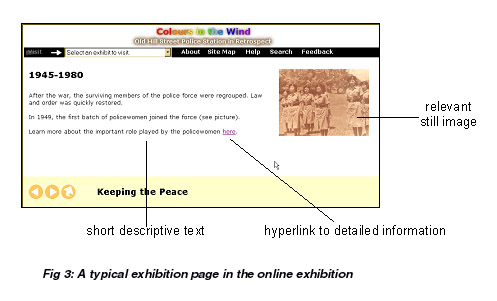

The original text of the physical exhibition was broken down into major topics, which were further divided into sub-topics based on the general flow of the original topic (see Figure 3). Due to time constraints, only the video clips in English were provided with English transcripts. English transcripts were provided to only the English audio clips but not for the Chinese, Malay and Tamil audio clips because of translation problems.

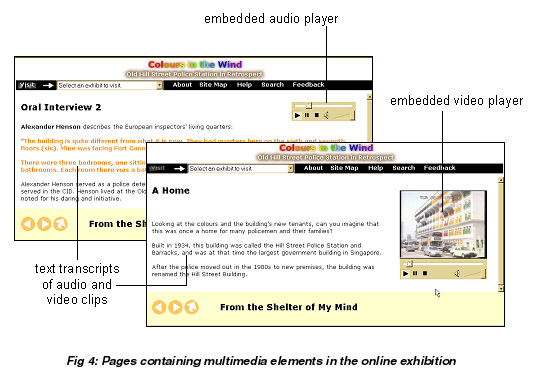

It was decided to embed the media player inside the web pages instead of playing media clips in a standalone player, which consumes more processor resources (see Figure 4). Furthermore, the standalone player would pop up in a separate window above the web browser, blocking the user’s view of the text transcript, which would be inconvenient for the user to close after the media finishes playing.

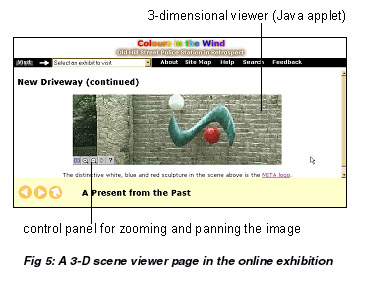

For architectural themes, a 3-dimensional viewer has been provided via a Java applet (see Figure5) that displays a slowly spinning view of selected sections of the Old Hill Street Police Station building. This provides a virtual reality interface that let the users explore parts of the building.

Online help pages are also provided for users to know how to use the site effectively. They present basic help information to users about the organization and use of each section. Each help page comprises of short text, mostly in bulleted lists for easier reading, and appropriate graphics. In fact, the general design of the online exhibition has been deliberately kept simple with the objective of making it intuitively easy for visitors to browse the site, even without looking at the help pages before foraying into the exhibit pages.

User Evaluation

An evaluation was carried out on the online exhibition through a questionnaire-based survey process. Of the total number of 30 participants, half of them were in their mid-twenties, with females outnumbering males by nearly two-thirds (63% females versus 37% males). Most of them were students, librarians, teachers and IT professionals. There was about 70% overlap in respondents in the user requirements and evaluation surveys. There was a good mix of professional backgrounds, particularly the students, librarians and teachers, who will be potential users of such exhibitions. Students are more particular about the critical design problems, while other professionals provide technical inputs on improving the efficiency and effectiveness of content delivery.

The majority of them (74%) felt that the text size chosen (Verdana 10 point) was appropriate and readable, and the use of colours, buttons and icons was appropriate (70%). The use of cascading stylesheets to control the formatting and general appearance of the pages in the online exhibition helped in the visual consistency of the pages. Stylesheets provide a powerful mechanism for maintaining a consistent and (most importantly) cross-browser look for all the pages. Surprisingly, though this site is simple and plain, nearly half the respondents (46%) found that the site was attractive. This could be traced to the fact that most of the respondents were adults who were more interested in content and simple presentation over excessive aesthetics to attract younger users.

The online exhibition is also an information system, and as such, the information must be organized in such a way as to allow the users to access information easily. About 67% of the respondents found that the organization of information was good. The contents were reasonably comprehensive (37%), although some respondents pointed out that there was too little details on certain topics at a few places. Therefore, more information along with links to other resources related to those areas needs to be provided. Due to the absence of a search engine, one-third of the respondents (33%) were neutral when they were asked about the ease of finding information within the site. Due to time and resource constraints, it was decided to relegate the development of a search engine to Phase II of the project, in which a proper search engine could be developed to index and search not only text but also multimedia elements such as images, video and audio.

Almost half of the respondents (57%) found that the exhibit selector (a drop-down list) was easy to locate. This was because the selector was deliberately placed at the top left-hand corner of the screen. Its presence was further highlighted with a flashing “Visit” animation beside it, and it was explained in the Help pages. However, a respondent suggested that the selector may be at the center of the navigation bar for better visibility. According to interface design principles, the top left-hand area of the screen is the most important one in terms of its visibility, so the selector menu was placed there. In general, the respondents found that navigation within the site is easy; even without reading the Help pages, the visitors are able to use the online exhibition. In terms of speed of downloading, the respondents generally felt that the pages loaded fast enough. This could be attributed to the basic design of the online exhibition site, which does not require the user to download special plug-ins, e.g. the Shockwave plug-in to view Shockwave movies.

Most of the respondents (90%) never read the Help pages before exploring the online exhibition. However, for those who did not do so, almost all of them (96%) agreed that the user interface was simple for them to browse without further assistance. For those who had gone through the Help pages, 60% of them found the details are sufficient to understand the system.

All of the respondents used the Windows operating system, and most of them (87%) were using the Internet Explorer browser compared to the Netscape browser (13%). In general, there was no problem in delivering the multimedia elements through both the browsers, since the drivers for playing back the clips were cross-browser compatible. Most respondents found that the media clips can be viewed. However, there were a few hiccups in video reception, resulting in jerky frames and the corresponding garbled audio narrative. It was found that this was due to the fact that the web server hosting the online exhibition was a Pentium I-based server without MMX capabilities to support multimedia.

On an average, 60% of the respondents felt that the window size of the video player, frames rate and the playing times of the media clips were acceptable. About 73% of the respondents found that the multimedia elements were useful in enhancing the learning experience, and the text transcripts were useful in aiding the understanding the A-V clip contents. A small percentage of the respondents (20%) encountered difficulties in loading the video stream, resulting in reading the text transcript without seeing the video, which was admittedly not an enhanced experience.

Ongoing Studies and Future Extensions

This project formed the basis from which advanced studies could be carried out in several directions. A large-scale requirements gathering study is going on with a 400-user sample from a myriad of professions, extending the existing study which was done solely with university students. In addition, a fully developed version of the online exhibition is being developed in HTML, and compared against the same exhibition with an animated user interface. Content delivery models will also be examined to find out the most preferred and efficient method of packaging and providing online heritage information to the public, for example, over the web, or delivery of information through CD-ROMs, etc. Another area under study is the management of digital media centers – their setup, media asset management and content management. Finally, the indexing and retrieval of multimedia resources using the latest programming approaches (e.g. Java) are also being explored.

Conclusion

This project has demonstrated the feasibility of using online exhibition systems to promote cultural heritage information in today’s world, based on the availability of modern powerful computers, communications technology, multimedia technology, and the Internet. Details of historical events can be brought alive via streaming video technology, which are becoming readily available to many users. However, the user interface of such systems must be kept simple so as to reach out to as many users as possible. In general, it was felt that a moderate level of interactivity was also needed to attract and retain the attention of the younger generation. Finally, the simple and best design will attract the visitors to visit the exhibitions again and again to gather more information, which requires the system to become a truly dynamic information system for the promotion of cultural heritage.

Heritage information systems have an important role in preserving and promoting the cultural information of the world, as well as help to foster global cross-cultural exchanges. By knowing what has taken place in the past, and appreciating the cultures of one another, the human race can then build a better world tomorrow – one where mutual co-operation and understanding reigns over conflict for the good of all mankind.

References

Dix, A. J., Finlay, J. E., Abowd, G.D. and Beale, R. (1998). Human-computer interaction: Second edition. Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited.

Faulkner, C. (1998). The essence of human-computer interaction. Hertfordshire, England: Prentice Hall Europe.

Ghezzi, C. et al. (1991). Fundamentals of software engineering. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kassay, M. (1995). Interactive multimedia in museums. [Online, January 10, 2001]. <http://online.anu.edu.au/CNASI/pubs/ OnDisc95/docs/ONL21.html>.

Spadaccini, J. (2000). Creating online experiences in broadband environments. [Online, April 7, 2001]. <http://www.archimuse.com/mw2000/papers/spadaccini/spadaccini.html>.

Sumption, K. (2001). Beyond Museums Walls – A critical analysis of emerging approaches to museum web-based education. [Online, April 7, 2001 ]. <http://www.archimuse.com/mw2001/papers/sumption/sumption.html>.

Thomas, S. (1991). Interactive media and the museum experience. In International conference on hypermedia and interactivity in museums. Pittsburgh, PA: Archives and Museum Informatics, pp 164-168.