Introduction

I had to detach myself from old habits

and learn a new paradigm, one that put people ahead of art, one that focused on

enabling not just engaging people

(Yenawine, 1999, 11).

In this paper we discuss the integration of visitor-contributed narratives into the narratives of art museums, within both curatorial and educational programs. We begin with a discussion of the goals of one particular project, the Art of Storytelling, a project that explores the parallels between visual and literary composition by encouraging visitors to compose creative stories inspired by works in the museum. Then we briefly touch on what we would describe as key factors in the success of such projects. We explore the motivations behind allowing visitors to contribute, drawing on a theoretical foundation that allows us to position visitor-contributed narrative as a valid articulation of the underlying goals for art museums. We then attempt to profile the current landscape of visitor-contributed narrative programs, drawing from evaluations of programs at a handful of art museums across the country. From this context we delve into a deeper examination of the Art of Storytelling project, beginning with a brief project narrative. This two-part project includes a curated selection of original visitor stories available via a podcast tour and an interactive kiosk activity in which visitors arrange original compositions drawing from museum works and record an original story about their work. This is followed by a description of and the results from our own modest evaluation of this project. We end with some additional insights we have gleaned.

Background

Over a year has passed since the completion of the first phase of the Art of Storytelling project, in which visitors to the Delaware Art Museum, both on-line and off, crafted original stories inspired by objects in the museum. In that time much debate in the museum field has occurred regarding the value – to the contributors, the museum itself and to the museum visitor community as a whole - of such visitor-contributed content projects. The verdict, from our vantage point, while still out in some respects, is overwhelmingly positive. Chiefly, in addressing the educational value – both cognitive and affective – to participants in such projects, we have found, like others before us (identified later in this paper), that projects evoking visitor storytelling are effective ways to engage visitors in thinking critically and creatively about, and responding to, art. Secondarily, these programs seem to benefit museums by both reaching out to and impacting new audiences, as well as by providing a potentially valuable feedback conduit with their audiences. In the third area of study – addressing the impact these programs have on the larger visitor audience – we have found intriguing, but inconclusive, results. On the one hand, some visitors have found the contributed content of other visitors inspirational, both enriching their museum experience and emboldening them to contribute in their own voices. On the other hand, other visitors have found the contributions of their fellow visitors outside their expectations, inappropriate, or even, simply, uninteresting. Additionally, a number of the programs launched by museums to encourage and enable visitors to contribute on-line have received lackluster participation. Do visitors see the museum’s carefully-crafted, expert panoply of voices as a place where their own voices would be vital, meaningful additions? Moreover, do visitors foster an interest in making those contributions, rather than simply relying on the museums to provide narrative insights? Our experience suggests “Yes” and “yes”, though not without a few important qualifications, outlined here.

First, not all museums, collections or exhibitions are deemed appropriate for or appealing to visitors as an opportunity to contribute. As Matthew MacArthur of the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History points out:

My staff and I were talking to a group of interns here at the museum, explaining our program which oversees the Web site. We thought it would be good opportunity to toss around some ideas for the future of the site with this group of young, smart students who undoubtedly all had their own Facebook profiles and were otherwise immersed in the world of Web 2.0. However, when it came to notions of user-contributed content on the site, all we got were blank stares. A few of them explained to us that as users, they would be looking for authoritative information from the Smithsonian, not input from other users or opportunities to participate. This group of aspiring museum professionals may not be a representative sample, but it definitely provided food for thought. (MacArthur, 2007, http://museumsremixed.blogspot.com/)

While the museum of reference was not an art museum, this concept of the museum providing a single, authoritative narrative regarding its collections, clearly shared by many in the art museum community, echoes a long-standing (and some would argue out-dated) model. On the other hand, the Smithsonian Photography Initiative recently completed a popular visitor-contributed photography project, on the heels of which they will be launching a visitor-contributed narrative project this summer; so the Smithsonian Institution, while authoritative and off-limits to some visitors, is a fertile environment for sharing to others.

We found the visitors of the Delaware Art Museum (investigated in greater depth in a later section of this paper) eager to participate in our storytelling project, with over 350 visitor stories gathered in less than six weeks. Many of the other projects outlined in this paper also show visitors contributing enthusiastically to museum narratives. So what does this mean? It is impossible to say with any certainty which museums, collections and exhibits are most appropriate for visitors’ contributions. Museum professionals must identify these themselves. We can say that in looking at our data we found visitors most likely to write stories about late 19th century illustrative, 20th century modern, and contemporary works, with which they were probably more familiar, both experientially and culturally, than about pre-Raphaelite and 19th century American art. This seems to echo what we already know: that people – visitors or not – are more likely to be inspired by and speak about what they know than what is archaic or alien to their experience.

Nowhere is this better exemplified than in one of the most popular visitor-contributed on-line projects we know: the Victoria & Albert’s one day project Tattoo: A Day of Record (http://www.vam.ac.uk/vastatic/microsites/tattoo/search/Blue/Introduction.htm).

About 1500 people came to the museum to document their tattoos, or more importantly, to have their tattoos displayed on the museum’s Web site. Identifying and providing relevant access points to your collections to enable visitors to contribute is a key factor in eliciting their involvement. In our case, it was a creative writing exercise that carries with it its own interest and audience.

Fig 1: Left: The most stories were written about Marooned, Howard Pyle, 1909, oil on canvas. Right: The fewest stories were written about The Return of Tobias, Benjamin West, 1803, oil on canvas.

In the past few years a number of art museums have introduced to their Web site visitors the capacity to create their own personal collections on-line. Some museums have even introduced additional features, allowing visitors to curate these collections with text and even audio, send them to friends, and even submit them to be viewed by other visitors. Unfortunately, many of these museums have been disappointed with the lack of visitor participation. Beyond a small group of technologists and intrepid educators, these visitor collection features often go unused. Some critics point to such failed attempts to engage visitor participation as further evidence that visitors are only interested in reaping the benefits of museum experiences, not contributing to them. We would disagree. But clearly a lesson can be learned from such lackluster participation. First off, it should be understood that this behavior, in which only the few are active contributors and the majority are passive visitors, is mirrored across the Internet on most user-contributed Web sites. Therefore it is best to structure projects such that visitors (and the project, for that matter) are not penalized for non-participation, but instead are able to enjoy, and perhaps be inspired by, the contributions of others.

Tied to this concept is the important factor of visitor motivation. In order to successfully garner visitor contributions, the museum must both remove barriers to entry and provide motivational factors. As will later be explored, the Denver Art Museum found that visitors were more likely to participate in a gallery-based narrative exercise when a curator was present, encouraging them to do so. Alternately, they found that visitors wanted clearer indications that their participation was invited. As we well know, museums asking visitors to contribute their own voices, especially in a creative capacity, is a relatively new concept, and in many ways directly counters visitor expectations – so inviting contributions loudly and clearly is the best approach.

In the case of the Art of Storytelling, we set up a Web site completely independent of the museum site, giving the project its own identity outside of the traditional Delaware Art Museum context. While we cannot say for certain if this was a success factor, we believe it didn’t hurt. More importantly, as a juried exhibition, selected storytellers were given a $250 stipend and had their stories professionally recorded for a museum podcast. Both were strong motivators, we believe. At the Denver Art Museum, visitors seemed to appreciate the ability to read each other’s narratives before contributing their own. While this was not evaluated as a factor in visitor motivation, it parallels user behaviors on Internet-based social media Web sites. People are not only more likely to go where others have gone before them, but are also more likely to perceive the value of doing so if they gain value from the contributions of others.

On the other hand, Web sites requiring logins to allow visitors to contribute, and other visitors to experience their narratives, establish barriers to entry. One exceedingly creative yet perhaps overly ambitious project by artist Flavia Da Rin at the Speed museum involves the following: Visitors must identify local billboards by the artist and enter an associated text SMS code to access a project site: http://www.ispyspeed.com. Only then do they read the contest rules: “Find the billboards and text each keyword to 55022. After each text you will receive a reply - each reply message will give you a codeword. Enter the codeword here to unlock the billboard image you found. When you've found 5 billboards, you can begin to upload your own billboard designs!” (http://www.ispyspeed.com) Visitors presumably then vote on their favorite billboard designs, and from these a winner is chosen. “The design entry with the most votes will be exhibited as a billboard outside the Speed Art Museum during the month of March 2008.” (http://www.ispyspeed.com) When we visited this site in January of 2008 with only weeks left in the project, there was only one visitor-contributed design to be voted on, and it had only two votes. While we cannot comment on the overall effectiveness of this project at this time, we will point out that the barriers to entry were formidable. And while the overall concept included an aspect of mystery and thrill that might appeal to some visitors, we believe the majority find the process cumbersome to say the least, and will not be bothered. Of course this is not a visitor narrative project per se, but a project that requires visitors to contribute creatively to the museum experience. We would argue that it is the museum, as much as the visitor (if not more so), who is privileged to receive the type of creative, thoughtful participation required. In order to motivate visitors to take part, the museum should make participation as simple, and rewarding, as possible.

While we upbraid the Speed Museum project as lacking in one of the key characteristics of success, we equally applaud the project for exploiting two other key success factors – promotion and audience. The Speed project was self-promoted by design, through the use of a series of billboards throughout the city of Louisville, tantalizing the populace with compelling works of art. This alone garnered a host of local press articles highlighting the project. In the case of the Art of Storytelling project, the uniqueness of the program and the nature of public participation led to write-ups in the major local paper, a radio story on a local NPR-affiliate, and mentions on various storytelling and creative writing newsletters and blogs. These outlets, some customary for the museum and some not, were vital in positioning the project and attracting participants.

Equally compelling (in our eyes) is the Speed Museum’s grand prize for the winning participant - having his or her creative work exhibited on a billboard outside the museum. This prestigious positioning for a local visual artist is a compelling accolade. Establishing an audience for your visitor-contributors provides them with something unique and otherwise unobtainable: affiliation with an esteemed institution, however mitigated by the guidelines of participation, is coveted by many. If, as so many on-line user-contributed Web sites have found, an active community built around the project can be established, the opportunities compound. But one danger we would identify is that many well-funded commercial on-line communities are vying for on-line visitors’ participation and time, so any expectations of developing thriving communities around your institution’s goals should be considered carefully. We would argue that the primary value that most art museums have to offer is in the connection that can be made by visitors to and around collections, not in fostering robust on-line communities beyond their collections. In the case of the Art of Storytelling project, winning stories selected out of our open call for submissions were included on the Web site and on a podcast tour of the museum. These venues, while they seemed to provide a compelling motivator to storytellers, are yet to be proven valuable to visitor audiences. Our initial attempts, as outlined in this paper, were encouraging in places, disheartening in others, and ultimately inconclusive. The fact remains that establishing a compelling audience for visitor-contributed content, an audience that appreciate this content and find their experience enriched by it, is a crucial factor in the formula for success.

Fig 2: A number of finalists for the Art of Storytelling project attending an opening celebration for the project.

Why Enable Visitors To Contribute?

For readers acquainted with our Museums and the Web paper last year expansively entitled Remixing Exhibits: Constructing Participatory Narratives With On-Line Tools To Augment Museum Experiences, or who have read Hilde Hein’s book Public Art: Thinking Museums Differently, this portion of our paper may be familiar terrain. But we include it here because we recognize that many museums, art museums often chief among them, remain skeptical regarding the value of visitors’ contributions to their experience. Many feel that it is the museum’s primary (perhaps sole) responsibility to engage visitors with, and inform them about, their collections, through compelling, authoritative narratives. And that this is, indeed, what their visitors expect and require. This debate, summarized nicely in Public Art by contrasting the philosophies of two vastly different museum directors, is as follows:

Alfred Barr, the first director of the New York Museum of Modern Art, had a vision of its collection as a single, complex, but coherent and longitudinal (i.e., art historically conceived) work of art that articulates modernism with impeccable, single-minded artistry. Julian Spalding, former director of the Glasgow Museums and Art Galleries, holds that museums should not tell one history but rather facilitate many concurrent stories. In his book The Poetic Museum, he proposes that the museum be something like a self-generated poetry anthology, permissively equipped with stimulating artifactual props… [He] encourages visitor/curator collaboration in the re-imagining of exhibits. (Hein 2006, 110)

It is clear from the introductory passage to Hein’s book, which of these philosophies she embraces:

I was one of the thousands of people drawn to New York by the Christo Gates project in February 2005… When a friend asked me afterwards what I thought of The Gates, I began by telling her about the light, air, sound, and color; the breeze; the cheerful people wearing saffron accessories; dogs in fashionable vests; children in strollers; bicycles… “But you’re telling me about everything else. What about the art?” “That is the art,” I answered. The art is its gestation, history the public it gathers and reactions it evokes, and the memories it leaves behind. It is a process, not a thing. (Hein 2006, xvii)

With this passage Hilde Hein ushers in the conceptual framework for her book. While here she speaks of public art, Hein moves on to apply public art as a viable model for museums. To do so, she begins by making the critical distinction that public art in its optimal form is characterized by the process, the reactions, the memories, of the public, rather than the objects themselves. She goes on to define the role of public artists:

Today’s public artists incline to replace answers with questions. They seek to advance debate and discussion. Their art is left open-ended and invites participation. Its orientation is toward process and change rather than material stability. Since its borders are indefinite, so is its authorship. (Hein 2006, 76)

She then offers up this conceptual model of public art for museums to consider. It is a model in which objects are still central, as they (more so than the narratives around them) have the capacity to evoke the “museal gaze…the gaze that endows the object with its aura [and] ‘‘revokes the disenchantment of the world.’” (2006,118) This somewhat lofty view of museum objects is one which many of us share, yet often struggle to inspire in our visitors.

In her public art model for museums, Hein provides the conceptualization of the museum itself as public art, in which questions of authorship and participation are raised rather than answered. In Public Art, Hein states:

I explore the affinity between museums and public art. I argue that museums are changing more ponderously and with less clarity of purpose but in a direction similar to that of public art. Most notably, I see both as actors that no longer presume a ready-made audience with a more or less fixed disposition. Rather, they set out to construct multiple publics of limited duration and variable character. (Hein 2006, xiii)

In her model, objects inspire and narratives are fluid and collaborative, drawing from the museum, the curators and the visitors. In this, the museum is “‘‘the controlling intermediary who sets the scene…then bids the actors take the stage and be their best artistic selves,’” (Hein, 2006,111) Here she is quoting Philip Rhys Adams, and goes on to suggest that by bringing the objects out of a traditional museal context, we can enable visitors to establish direct, personal, perhaps even artistic, connections.

From the museum's perspective… the object remains central, but its multidimensionality is accommodated in a manner that partially detaches the object from the museum context and dematerializes it. The performance of certain ritualized acts by appropriately empowered persons sanctions a temporary demusealization of the object and its reinsertion into the life stream. (Hein 2006, 124)

Here Hein is speaking of a group of Tibetan monks who create a mandala at the Davis museum in Wellesley College. It is this sort of integration of ritual use of objects in the museum context which “demusealizes” these objects and makes them more relevant to our real lives.

We have found something similar to occur with the Art of Storytelling project, where by selecting works of art to write about, visitors bring these objects into their own lives. One participant discusses these objects in the context of her creative writing group: “I periodically think back to the works of art from the contest, especially since I’m in a writer’s critique group, and most of our members participated in the contest. We've discussed the stories and works of art many times.” To have permanent collections be the source of ongoing discussions in local communities is an aspiration shared by many museums.

Fig 3: “After creating my own story to accompany a wonderful art work, I felt connected to the museum, like I'd left my own footprint by engaging in the creative process.”- Virginia Hertzenberg, author of a short work inspired by Queen’s Closet

While Hein discusses at length why museums should adopt her model, she provides few examples of the practical application of her model in the field. She provides no specifics relevant to the Internet, though she does suggest the potential that these technologies offer to both support and extend her theoretical framework: “Electronic communication technologies have orbited far beyond Malraux's photographically facilitated “museum without walls.” They now offer worldwide access to museums interactively, replacing physical contact and one-way communication with intangible lines of exchange (Hein, 2006, 116). She states:

[T]he “virtual museum” can be an avenue to information exchange unformatted by the authoritative voice of the museum. “Virtual visitors” to some museums now exceed actual ones numerically. They can freely rearrange their downloaded treasure and shape it into “collections” of their own devising, however and in the company of whomever they like. Like the emerging public art, whose identity lies in its process, the “virtual museum” is ephemeral. Its vitality lies in the capacity to meet contemporary needs with contemporary means. (Hein, 2006, 117)

The Art of Storytelling project outlined herein is one such “contemporary mean”. And while we identified a few other compelling on-line projects that address the concept of visitor storytelling and narratives in the art museum context, we found none that had been, as of yet, formally evaluated. What we did identify were a number of visitor-contributed narrative projects in an art museum context that, while not technologically facilitated, have been evaluated, and provide compelling research insights into this concept.

Visitor Narratives in Art Museums

Art museums as institutions have the unique opportunity to encourage visitors to foster connections with objects that have shaped culture throughout history. Programming that incorporates an interactive component, casting the visitor as “storyteller” in the creation of visual or written content inspired by works on display, is a particularly effective tool for reinforcing art’s role as a catalyst for meaningful connections. Whether integrated with public school curricula or unique to a particular exhibit, museum programming that asks visitors to develop original content in response to art, and occasionally makes that visitor-contributed content itself a component of the exhibit, has proven itself a viable resource in various ways. This programming not only encourages the development of critical thinking and visual literacy skills in students, but also and more broadly engages museum visitors of all ages in the meaning-making process.

To borrow a phrase from Janna Graham and Shadya Yasin’s essay entitled “Reframing Participation in the Museum: A Syncopated Discussion,” participatory exercises in response to artwork allow a museum to transcend the burdensome stigma of static institution and instead become “a laboratory for the exploration of relationships between cultures and art forms”, (2007, 169) and with that, a prime locus of learning. With arts programming in public schools often overlooked, schools are increasingly partnering with museums in hopes of sharpening students’ critical thinking skills. One popular tool used in this partnership (many of our readers will already be familiar with it) is Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), the capstone program from Visual Understanding in Education, a firm specializing in educational research and the development of elementary school curricula. Developed over a decade ago, VTS aims, through a series of art and writing projects on museum artworks, museum visits, and an ongoing classroom component, to teach young students how to “examine and find meaning in visual art” (http://vue.org/whatisvts.html). Two museums which successfully partnered with neighboring public schools to put arts curricula into action are the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, and The Wolfsonian Institute in Miami.

Educational Programming

Thinking through Art at the Gardner Museum, evaluated in a three-year (2003-2006) study of “student learning in [the Museum’s] already well-established School Partnership Program” (Burchenal & Grohe, 2007, 5) turned to a Visual Thinking Strategies curriculum in efforts to teach elementary school students the fundamentals of how to “look” critically and constructively. In order to assess student gains from the program, in which students wrote a variety of essays in response to significant work in the Gardner collection, a “critical thinking rubric” of seven primary skills was used: Observing, Interpreting, Evaluating, Associating, Problem-Finding, Comparing and Flexible Thinking. The goal was for students to engage with the artwork through practising their “active looking” skills, teaching them to deconstruct what might otherwise have been an alienating work of art and use the visual components they observed to build a successful argument in writing. The critical thinking rubric was used to measure improvement not only in the students’ written work throughout the course of the program, but also in their class participation and discussion. Though the published materials on Thinking Through Art do not present quantified results on academic gains,

this study confirmed through research what many museum educators have come to believe through personal experience: that regular practice in looking at and discussing works of art using the VTS technique is remarkably effective in developing students’ capacity to think critically. Our results… bolster the argument that learning to look at art should be an integral part of every child’s experience. (Burchenal & Grohe, 2007, 17).

Participatory exercises at the museum have also garnered positive results without as formal a relationship to academic work.

In a three-month long program run from Feb-April 2006, the Wolverhampton Art Gallery asked students in neighbouring schools to cast themselves as “storytellers” in a more organic sense, utilizing oral storytelling, creative writing and dance exercises facilitated by visiting artists and performers in the classroom to get young museum-goers excited about and inspired by art. “Storyteller/writers…[worked] with the 3 schools in Wolverhampton to develop creative oracy and literacy [skills] using artifacts contained within the Silk Road themes loan box developed by the Wolverhampton Art Gallery” (Wolverhampton, 2006, 2). The objectives of the programming seemed to be to first inspire students through unique artifacts and engaging dance and storytelling performances, and then use these stimuli to “develop…literacy skills, particularly in regards to creative writing” (Wolverhampton, 2006, 3) and encourage use of each one’s own “authentic voice” (Wolverhampton, 2006, 6).

In fact, each evaluation presented programming assessed via a unique rubric, yet a common thread through most was the goal to improve literacy as defined by standardized test scores. A constant emphasis in public school curricula, improvements to literacy test scores are therefore an important component to curricula developed through museum partnerships. While there were significant increases in other areas such as creativity, communication and connection, none of these programs reported statistically significant improvements in literacy test scores.

Test scores aside, the positivity and enthusiasm for art and learning successfully channeled through these programs were also embraced by the Artful Citizenship Project at The Wolfsonian, in partnership with several Title 1 elementary schools in Miami. Like the Gardner museum, Artful Citizenship also used a VTS based curriculum and incorporated academic goals similar to those of the Gardner museum, the Guggenheim museum (mentioned later) and the Wolverhampton Art Gallery. Yet what made this program unique was that in addition to bettering scholastic skills, its “arts-integrated social studies curriculum” sought to improve the 3rd -5th grade students’ psycho-social skills in efforts to teach responsible citizenship. Through Artful Citizenship, students were able to do a number of hands-on art activities that engendered great enthusiasm, including “travelogues, dioramas, [and] drawing activities” (Curva and Associates, 2005, 74), all inspired by the socially-conscious collection at The Wolfsonian.

Kate Rawlinson, of The Wolfsonian’s education department, praised the program’s use of “visual elements, an incredible [resource to] improve remedial skills” in students. Yet Rawlinson’s true measure for the success and importance of the Artful Citizenship Project was the students’ excitement about participating. “Kids want to do Artful Citizenship” says Rawlinson; “they enjoy it- how many opportunities do young people have to express their opinions and be listened to?” (personal communication, January 2008)

For students, undoubtedly one of the most impacting components of the program came during its final portion, the visit to The Wolfsonian. “The purpose of the visit was to allow students to directly experience and reflect upon the images and artifacts on exhibit” (Curva and Associates, 2005, 12). The artwork they created during Artful Citizenship was formally displayed at the museum as visitor-contributed content, label and all, generating pride and enthusiasm in the students. Their artworks, noted Rawlinson “were handled like any artwork in the museum” (personal communication, January 2008), and established the museum as a personally meaningful place where their creative visions and contributions were valued.

Another successful partnership was fostered between the Guggenheim and local NYC public schools for its Learning Through Art initiative. In addition to improving students’ critical thinking and writing skills through art-making and writing exercises, Learning Through Art, like other partnership programs discussed, sought to improve literacy test scores. While no marked improvements in scores were revealed through comparing the English Language Arts test scores of control students vs. Learning Through Art participants, student questionnaires revealed the treatment group showed more positive attitudes towards art and the study of art. Through open discussions about art at the Guggenheim, essays on important paintings, and teaching artists in the classroom developing art projects alongside teachers, students learned the skill of “close and careful looking” (Randi Korn & Associates, 2007, 148) at artworks and the visual elements within them. With that foundation, they were able to make connections between those elements not only to improve their writing, but also to create original artworks individually and as a class, inspired by art at the Guggenheim and elsewhere.

Senior Education Manager of the Learning Through Art program Rebecca Shulman Herz recalls a memorable project involving teaching geography to students through the exploration of space. Students learned about “intervention artists” Christo and Richard Serra, among others, and the innovative ways in which their installations interact with their environment. The culminating exercise for students was the building of their own outdoor installation, inspired by a theme of “peace”, around their playground. “The kids were put into the role of the artist, and taught how to investigate” says Herz, and with this firsthand knowledge, coupled with class lessons on specific artworks, students visited the Guggenheim and participated in discussions with docents where they “were treated as the experts” and allowed to voice their knowledge and impressions of the works (personal communication, January 2008). Like at The Wolfsonian, Learning Through Art employed visitor-contributed content in its programming, with student-created works put on display for the final museum visit, an exhibit that also went up at the schools so as many kids as possible could see their artwork hung. Kids were encouraged to respond to their fellow students’ works through postcards at the exhibit which they could write and mail back to the school, so that classmates could get a tangible sense of the impact art can have.

Curatorial Programming

Visitor-contributed content has also been a significant component of museum programming outside of school partnerships; multiple programs developed by the Denver Art Museum, particularly those centered around their new Hamilton Building, have incorporated it as a meaningful way in which to engage visitors. The contributed content created by visitors during these interactive programs was not artwork; it instead took the form of a public, communal journal placed in certain galleries as part of the Caitlin Cubes, What is West?, Western American Art, Pacific Story, and Frederic Remington: The Color of Night programs.

The writing exercises for the above exhibits included poetry writing, and journal entries in response not only to artworks, but also to question prompts integrated into the exhibit. Activities were designed to be done in a communal journal, and the reading of previous entries was encouraged for inspiration. Many of these journal writing activities also included the option to listen to pre-selected inspirational soundtracks on an iPod. Regarding the “Caitlin Response Activity” in particular, which asked for visitor responses to different opinions presented on what is considered the Museum’s most controversial painting (Caitlin’s portrait of himself painting a Mandan Chief, 1848), “many interviewees said it was interesting to read other visitors’ perspectives and opinions” (Randi Korn & Associates, 2007, 15) on a complex work, and all but one individual interviewed took the time to read others’ responses.

About the “What is West?” Response Activity, where visitors were given a place to sit, read others’ entries, and write their own thoughts in the public journal on the meaning of the West, one visitor commented: “what I wrote was passionate. If I stop and think about it, I am outraged at what we’ve done to the American Indians in the wake of Manifest Destiny. While a lot of these paintings glorify the West, there’s a dark side to this history that we…ignore” (Randi Korn & Associates, 2007, 20).

Visitors to the Denver Art Museum’s special exhibition “Frederic Remington: The Color of Night” had the opportunity to engage in new types of writing activities in the galleries. “Frederic Remington: The Color of Night” also

provided an opportunity for museum staff to develop new types of writing activities for visitors,[as] two different types of poetry writing booklets were placed at each of two seating areas in the gallery, encouraging visitors to reflect on Remington’s paintings of nighttime themes and subject matter. Since a poetry writing activity is also planned for the Western galleries in the Museum’s new wing, the Remington activities were used as a pilot study. (Musynergy, 2004, 5)

Responses to this type of programming were positive overall, with visitors coming away feeling that their perspectives on the work were changed for the better, as the activity promoted involvement with the works and helped them make connections amongst exhibited works by Remington. Additionally, visitors’ comfort levels in the gallery increased, though many interviewees noted they would have wanted clearer “permission” (Musynergy, 2004, 15) to participate in the activity. One visitor to the Remington exhibit who participated in the writing activities said they were “another way of opening up, responding to what you’re seeing and pulling everything together. It’s not just a visual thing, it’s an emotional thing, a spiritual thing” (Musynergy, 2004, 14); clearly meaningful connections were sparked not only through asking museum goers to reflect on art, but also by giving them access to the thoughts and writings of other visitors just like them. Lisa Steffen, Master Teacher for Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum, who worked to develop these gallery activities, speaks to their significance:

The struggle we keep coming away with is how to entice adult visitors to do activities that are intended for them. When we ask adults to do an activity in a testing situation, they say they wouldn't have done it on their own in the gallery – but we also hear that they both enjoy it and have a deeper experience with the art. It's not easy, but with [such] outcomes, the challenge to overcome preconceptions and draw folks in is well worth taking on. [Steffens continues:] when we test response activities, we often see/hear evidence of things happening that we care about – the visitor spending more time with an artwork, looking longer, looking more closely, making personal connections, etc – and that's enough to make us want to create conditions for that to happen more. (personal communication, January 2008)

While interactive activities are arguably useful tools with great potential for both museums and their visitors, it is important to note that not all activities across the board are met with positive results. Aside from literacy concerns with school partnerships, the program evaluations from the Denver Art Museum revealed that not all visitor responses were entirely positive. Key issues which emerged both with the writing activities in the public journals and the art-making activities in the galleries included reconciling gallery activities involving touching, writing, drawing etc. with traditionally “appropriate” museum behavior, age-appropriateness of the activities for adults vs. children and families, and intimidation faced both when asked to develop original creative content in a museum environment and when faced with a self-guided activity that didn’t have an instructor or museum professional playing a supervisory role.

The issue of decorum seemed minor, with visitors usually intrigued enough by the activity to approach it anyway, though the study concluded that it was important to emphasize that “the Denver Art Museum is different than other art museums” (Musynergy, 2004, 8) and encourage visitors to “move beyond their initial reservations” (Musynergy, 2004, 8) about what one does in a museum.

The question of age appropriateness was posed mainly in response to the art-making, not writing, activities; while many parents commented positively that the activities would be fun for kids, “nearly all interviewees said when they first approached it, they thought the postcard-making activity [among others] was intended for children” (Randi Korn & Associates, 2007, 4). Adults also seemed confused at the activities that included traditionally kid friendly materials such as “rubber stamps and colored pencils” (Randi Korn & Associates, 2007, 4). It seemed that the journal-writing activities were more relevant and engaging to adults overall.

Intimidation, while difficult to quantify, is a key component to consider when using interactive programming as a positive and progressive tool in rethinking meaning-making in museums. In response to the Frederic Remington poetry-writing activity, one participant noted “when I think of poetry, I think I can’t possibly do that” (Musynergy, 2004, 9). It is not only the requirements of the museum activity itself that can make visitors feel insecure in their skills, but also and perhaps most significantly the call to creativity that can seem daunting. A suggestion gleaned from a panel study of visitors conducted to assess the Frederic Remington poetry-writing activity was for the museum to “try incorporating an icebreaker question” (Musynergy, 2004, 9) to ease visitors into the idea that the creative process can be embraced by anyone. The activity could be introduced with language that opens doors to all participants, such as “although we are not all artists or poets, we’re all creative in some ways….” (Musynergy, 2004, 9)

Interactive Programming

Whether affiliated with school curricula or developed around a particular exhibit, interactive programming holds great potential to involve, engage and reward the museum visitor and the institutions themselves through allowing a new forum to establish valuable relationships with art. The next step might be channeling the creative and learning processes engendered through this programming and coupling it with new technologies to speak to an even wider audience. One such program which utilizes technology as a vehicle for visitor-contributed content is set to launch this spring at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum. Called Round and developed by artist Halsey Burgund, it is

an audio installation that will solicit spoken voice contributions from visitors and use them as part of a musical composition intended to be listened to while viewing the work on [display] in the galleries. The interactive audio experience will allow visitors to hear a diverse range of voices – including artists, curators, and visitors – sharing their perspectives about the exhibitions and to add their responses. The comments will be collected in a database of recordings and subsequently incorporated into the piece. Thus, there will be a continual loop of opinion and emotional response, all contained within a musical work. The flexible infrastructure developed and built for the installation will be the basis for future audio tours at the Museum. (personal communication, January 2008)

Educator at the Aldrich Laura Kaufman reinforces that the goals of this exhibit correlate with the goals of the education department to encourage building more personally meaningful relationships between visitors and artworks.

This project fits perfectly with the philosophy of The Aldrich education department to provide connections between the artists and viewers through active engagement with the actual art objects and artists in our exhibitions. [Comments Kaufman] by responding creatively to contemporary art and honoring the experiences of our diverse communities we aim to unlock ideas about the greater world. The interactive component of Round and the subsequent audio tour, Pause. Play is critical in achieving meaningful exchange. (personal communication, January 2008)

The Art of Storytelling at the Delaware Art Museum also utilizes new media to implement innovative programming, attracting visitors to respond to art and create their own stories through gallery tools that go beyond pen and paper. Interactive kiosks allow children to construct visual and written narratives that incorporate elements of the art they see around them on display, cultivating an immediate connection between the museum and their personal artistic exploration, while podcasts of original stories written by museum visitors on works at the Delaware Art Museum allow museum-goers the chance to experience alternative narratives to the authoritative curatorial viewpoint hallmark to audio tours.

The Art of Storytelling Project

Before discussing the results of our evaluation, it is worthwhile to take a step back and present all of the components of the Art of Storytelling project cohesively. In 2006, the Delaware Art Museum sought to create a collections-based museum education project geared to children ages 8-12. The objective was to enhance young museum-goers’ appreciation for the visual arts through the wonders of storytelling; this program would explore both the stories expressed through art and the stories behind the artwork. To implement this vision, Night Kitchen Interactive collaborated with the Museum’s curatorial and education teams to develop a three-part educational program designed to inspire audiences to make connections between the visual narrative of art and the tradition of storytelling.

The Art of Storytelling program began with a call for entries from storytellers, artists, writers, and dramatists around the world; over 350 entries by 116 storytellers were submitted, and twenty were featured in a podcast of narrated stories available as a self-guided gallery tour at the Museum. The primary goal of all of the stories was to bring new interest, excitement and meaning to the work and to encourage learners to engage with the work on an entirely different level than they would have by simply viewing it in the gallery. A kiosk-based gallery activity was developed to provide storytellers with the opportunity to tell their own stories by creating their own, unique compositions based on the images and words from the Delaware Art Museum collections. The Picture a Story interactive kiosk invites storytellers of all ages to create their own masterpiece and inspired story using elements from works in the museum. This interactive activity first involves the building of a scene, including the selection of genre, character, and props, which can be resized to fit anywhere on the chosen background. Once the picture is created, users are encouraged to write and record a narration of their own story, detailing their interpretation of what is occurring in their newly-crafted portrait collage. A final phase of the project, currently underway, is the launch of an Art of Storytelling Web site, where on-line visitors can experience stories, tell new stories about works in the museum, and engage in the Picture a Story interactive activity previously only available at a kiosk in the museum. Through this site the museum intends to continue to cultivate a collection of stories inspired by its collections.

Fig 4: The future homepage for Delaware Art Museum’s The Art of Storytelling Web site, launching in April, 2008.

Our evaluation looked at the impact of these project components not only on students in participating schools, but also on the storytellers who contributed their narratives in the call for entries. The information we collected provided some interesting observations, and reinforced the view that interactive programming, particularly that which incorporates visitor-contributed content, holds for museums to build closer relationships with their visitors.

Evaluation

In order to determine if visitor-contributed content was in fact of value to those who contributed, and to assess the value of the project to the Delaware Art Museum, the writers of the Art of Storytelling stories were surveyed by e-mail about their experiences since writing the story. In the year since the call for entries, had participation in this project altered their lives, especially in regards to thinking about art either in- or outside of art museums? Does the way they think about art support art museum goals for visitor outcomes?

Overall, we found that the process of writing the story had a positive effect on the writers, and in ways which art museums would find useful - visitor engagement and interest in the artwork.

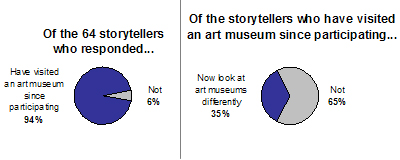

First, the fact that 55% (64 of the original 116) of the storytellers responded to our survey shows a long-term commitment to the project.

Fig 5

Second, participation seems to have a positive effect on continuing relationships with art museums: 92% of those returning the survey said that they felt more connected to the artwork or to the Delaware Art Museum because of the story-writing experience, and of these people, 59% also felt a greater connection to art museums in general.

Fig 6

While we do not know what the museum-visiting behavior of this group was before the project, 94% have visited an art museum since participating in the Art of Storytelling project in the summer of 2006. “It made me realize how visual input can influence creative output, and how enjoying art is not a passive, but active pursuit” answered one respondent.

Fig 7

Third, the relationship with an art museum may be deepened because of participation. Twenty-one people who have visited an art museum since submitting a story now look at art in museums differently. Of these, 52% look for stories in art work, 24% find more personal meaning from their viewing, and 10% simply say it is more fun now to view art. All of these outcomes not only are positive for the participants but also indicate that the project supported the art museum in developing more appreciative and educated patrons.

Fig 8

Fourth, participation positively influenced how writers experience works of art and the art-making process in general, illustrating the art museum’s ability to affect people’s lives beyond the institution. Of the 34 people who articulated the ways in which they were influenced, 26% noted that participation has changed how they view art when they visit art museums; 29% have even continued to think about the artwork for which they wrote their story and, in some cases, have done additional research on that work outside of the art museum environment. Even more encouraging, 33% of participants said that the act of writing a story for this project made them more creative in their own art, be it written work or in other media.

Fig 9

The long-term impact of The Art of Storytelling project also may be documented in a small evaluation project done to assess the impact of the project on an audience who used, rather than contributed, content for the project. Through an educational program, The Delaware Art Museum presented selected audio stories to elementary school students. Students then wrote stories both before and after their visit, using one of the artworks as a prompt. They also had the opportunity to use the Picture a Story interactive activity developed with this project to compose their own original artwork and accompanying story. As a control, a parallel group of students did not listen to the stories on the iPod while in the galleries, nor did they use the interactive kiosk. All had the opportunity to write their own stories in response.

Two classes were surveyed in two studies. One group of 40 students came from a charter school with an on-going relationship with the Art Museum. These students visit the museum often, and their teachers have access to museum resources; therefore, they might be considered more “expert” visitors (McDermott-Lewis, 1990). The other group of 29 students was from a neighborhood school where the students traditionally have less exposure to art and museums. The pre- and post-writing exercises of the groups were analyzed for creativity, and the students were surveyed about their field trip experiences about three months after their visit. The criteria for creativity as defined by the museum staff were an increase in the length of the story and the number of adjectives used, and the inclusion of visual details from the artwork in their story.

This evaluation did not find that exposure to the audio stories made a significant impact on the students’ story writing. Especially for students from the charter school, there was little positive change, either in the creativity measures or in the specifics of their Picture a Story kiosk exercise. There was an increase in creativity measures, however, for students from the neighborhood school; while their post-writing skills did not reach the level of the charter school students’ pre-writing skills, the increase in creativity might indicate that the use of inspirational, visitor-contributed content may be a way to reach more novice visitors. These findings correlate with those of the various school and museum partnerships explored earlier in this paper, where creativity, as measured by varying rubrics, and other affective values increased through interactive programming, while concrete literacy gains, as measured by standardized literacy tests, were not obtained.

For both groups, though, there was good recall of the museum visit and of the audio stories, when used. Three months after the visit, students could remember details of the two iPod stories, as well as of the art work these stories were inspired by, even though the artworks were not what they remembered as their “favorites.” This observation suggests that use of visitor-contributed content may be a way to affect cognitive learning for audiences of the content, as well as a way of producing affective changes for the contributors themselves; at the very least, it seems a method to entertain and thus engage participants.

Fig 10: Courtney Waring, Delaware Art Museum visiting a participating school.

Overall, the use of programs like the Art of Storytelling seems to meet art museum goals of developing observation skills, critical thinking, and personal meaning making. They seem less likely to satisfy classroom teachers who are looking for gains in literacy skills related to writing. However, more in-depth assessment needs to be undertaken. In the writing exercise evaluation, the researchers note that the choice to use the same painting for both the pre- and post-writing exercise, for instance, may have discouraged the creativity of some students during the post-writing experience. Many complained that they had already said what they had to say about this painting. Some decided to write a sequel to their previous story, in which they rehashed the first. This is clearly not the best assessment of creativity. In addition, there were a variety of factors that impacted the students’ museum experience differently, largely due to disparate guiding styles. This made it exceedingly difficult to compare across groups. A more tightly designed research project would better assess the potential impact that visitor-contributed content could have on students’ writing abilities.

Conclusion

While technology-assisted, visitor-contributed narratives clearly reside in a burgeoning field of study, and within that field the Art of Storytelling project is in its early stages, the initial findings are compelling. In April of 2008, parallel to the publishing of this paper, the Art of Storytelling Web site will be launched. We look forward to tracking visitation and contributions to the project when it is available on-line, allowing us insight into another piece of the puzzle.

Clearly we have found that, like many of the other projects outlined in this paper and in concordance with the theoretical framework outlined earlier, participation in visitor-contributed content programs at art museums is valuable to the participants. Similarly, we believe, though we do not have the quantitative data to prove, that these programs offer museums valuable insight and interaction with new and existing audiences. The third and final part of the equation, the value that these programs provide to the general public of museum visitors, is yet to be completely clarified. For example, the Delaware Art Museum is still unsure of how to effectively utilize their podcast tour outside of an educational context. As the material is not of a traditional curatorial nature, it does not integrate with regular visitors’ notions of a podcast tour, so its employment in that capacity is limited. The original intent was to use it with elementary school students as a podcast tour in the context of a gallery-based educational activity, followed by a story-writing exercise performed on the museum’s storytelling kiosks. While their use is not always followed by the kiosk activity, the podcasts themselves have become a fixture in a language-arts-based tour for school groups entitled Painting with Words. The museum’s latest effort to meet educators’ needs by establishing that the program addresses literacy curriculum was inconclusive as best. This is not surprising, as other programs addressing literacy in art museums have also come up with limited to no substantial impact on literacy test scores. Most important, the project as it was originally conceived was never meant to address literacy, but instead to impact the cognitive areas of creative thinking and visual literacy, and the affective areas of self-confidence and establishing voice. Unfortunately, our evaluation did not adequately and effectively address these areas of learning. All in all, a key dilemma remains. If we cannot find an appropriate outlet for visitor-contributed narratives in the museum experience, either on-line or at the museum, then we cannot entice visitors to contribute stories with false claims of audiences who do not, ultimately, exist.

While all of this probably comes across as rather negative in the end, we hope not. We believe that the audiences and the contributors are out there. We have seen and heard enough from visitors exposed to the Art of Storytelling project – both on the storytelling side and on the audience side – to feel strongly that there is an appropriate use for this sort of visitor-contributed content. We simply believe that the optimal educational program for doing so, and an accurate mechanism to evaluate such a program, is yet to be determined.

In closing, we refer to Kate Rawlinson, Artful Citizenship Project Director and Assistant Director for Education and Public Programs at The Wolfsonian.

For me it is a political/humanistic argument. We all gain from the dialogue that interactive museum programming nurtures. When a museum visitor (or student in a school-based program … like the Artful Citizenship project) is encouraged to respond to art or their learning/viewing experience of it – that is to be actively and personally involved in a meaningful dialogue – you put a complex set of human thoughts and feelings into play. Not only are you validating the visitor’s/student’s right to have an authentic response in a setting that often disempowers the non-initiated, but you (the museum educator) are also placing them and their experience at the center of your practice. It is a significant shift of power that benefits all who experience it as it opens doors of communication and human exchange. (personal communication, January 2008)

As a final note, here are a few comments from our storytellers regarding the Art of Storytelling project: “I see art as much more fun now. I am not nearly as shy when it comes to looking in depth at more intricate works of art. I enjoy the challenge these paintings provide.” “I think I have given more validity in my own mind to personal interpretations of artwork, rather than one right or wrong interpretation.” “It made me realize how visual input can influence creative output, and how enjoying art is not a passive, but active pursuit.” “I think I have given more validity in my own mind to personal interpretations of artwork, rather than one right or wrong interpretation.” “This contest’s IDEA has expanded my definition of the word “view.” These comments, more than anything else, suggest to us that visitor narratives have a place in museums.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Danielle Rice and Courtney Waring of the Delaware Art Museum, Stephanie Luccia, Heather Jo Wingate, and Erin Kelly of the Museum Audience class at The University of the Arts in Philadelphia, Kate Rawlinson at the Wolfsonian Institute, Rebecca Shulman Herz at the Guggenheim Museum, Lisa Steffen at the Denver Art Museum, Laura Kaufman at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Colin Wiginton at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Margaret K. Burchenal at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and Kara LaFleur at Night Kitchen Interactive.

References:

Burchenal, Margaret K. & Michelle Grohe, (2007). Thinking through Art: The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum School Partnership Program. Journal of Museum Education. 32: 2 (Summer 2007). 111-122

Curva and Associates (2005). The Wolfsonian Inc: Artful Citizenship Project Three Year Project Report. Retrieved December 14, 2007 from http://www.artfulcitizenship.org/pdf/full_report.pdf

Graham, Janna & Shadya Yasin, (2007). Reframing Participation in the Museum: A Syncopated Discussion. In G. Pollock & J. Zemans (Eds). Museums after Modernism: Strategies of Engagement (pp. 157-172). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Hein, Hilde (2006). Public art: Thinking museums differently. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

MacArthur, Matthew (2007). Museums Remixed: Trust in museums, trust in the audience. Retrieved January 2, 2008 from http://museumsremixed.blogspot.com/

McDermott-Lewis, Melora (1990). The Denver Art Museum Interpretive Project. Retrieved December, 5, 2007 from http://www.denverartmuseum.org/files/Files/daminterproject_1.pdf

Musynergy (2004). Denver Art Museum: Visitor Panel Study of Poetry Writing Activities in the Special Exhibition Frederic Remington: The Color of Night. Retrieved December 14, 2007 from http://www.denverartmuseum.org/files/File/vispanelpoetry.pdf

Randi Korn & Associates, Inc (2006). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Matthew Barney: Drawing Restraint Interactive Educational Technologies & Interpretation Initiative Evaluation. Retrieved December 5, 2007 from http://www.sfmoma.org/extras/documents/RKA_2006_SFMOMA_Barney_distribution.pdf

Randi Korn & Associates, Inc (2007). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Teaching Literacy through Art Final Report: Synthesis of 2004-5 and 2005-6 Studies. Retrieved December 5, 2007 from http://www.informalscience.org/download/case_studies/report_221.PDF

Randi Korn & Associates, Inc (2007). Remedial Evaluation Adult Art-Making and Responding Activities prepared for the Denver Art Museum.

Speed Art Museum (2007). Flavia Da Rin’s project I Spy Speed. Retrieved January 11, 2008 from http://www.ispyspeed.com

Victoria &Albert (2000). One day project Tattoo: A Day of Record. Retrieved January 2, 2008 from http://www.vam.ac.uk/vastatic/microsites/tattoo/search/Blue/Introduction.htm

VUE: Visual Understanding in Education (2001) Understanding the Basics. Retrieved January 4, 2008 from http://vue.org/download.html#moma

Wolverhampton Art Gallery (2006). Creative Learning Project Evaluation ‘The Silk Road’. Retrieved January 4, 2008 from http://www.renaissancewestmidlands.org.uk/ local/media/downloads/Wolverhampton%20Evaluation%20Final.pdf