Introduction

Lugano is a small city in Canton Ticino, the Southern part of Switzerland. The city blends Italian culture and Swiss hospitality, and enjoys a rich cultural heritage, from Renaissance frescoes to modern architecture and to monuments from the Italian Enlightment. Lugano is a common destination for primary and secondary school classes during their field trips from all over the region. According to school programs, the goal of such field trips is different according to grade. “Learning about your city” is an overarching learning goal for grades 8 and 9, so that visiting the city means understanding its structure, history, and life. In higher grades, cultural goals are more important, and a visit to Lugano is a way to (a) see the cultural heritage of the city, its history and artistic treasures; and (b) understand the city as a lively economic space, manifested through shops, banks, tourism, etc. Finally, for schools from rural regions, a visit to Lugano is also a way to (c) experience the city as an urban space different from the mountains and countryside.

Careful planning, preparation and follow-up allow teachers to turn school trips into real learning experiences, at the same time engaging and memorable for children. CityTreasure was designed for supporting teachers in this process with a pinch of technologies, blending mobile phones and outdoor learning activities. CityTreasure is basically an SMS-based treasure hunt through the streets of Lugano, targeted to school classes from grades 8-12. It capitalizes on the results of an eTourism project (eTreasure; Cantoni et al., 2008), and was developed in collaboration with the city school district. The challenge of CityTreasure is using mobile technologies for blending curriculum-relevant content into an engaging activity fostering observation, active learning and retention in a powerful informal learning experience.

The paper is structured in three sections. The first section, Related Works, provides an overview of the theoretical basis of CityTreasure and reports on related works. The second section, Children Hunting for Treasure, describes the technologies, the design of the game and the development of content, as well as implementation with the schools. The third section, Evaluation, presents and discusses the evaluation. The conclusions follow.

Related Works

Location-based games and city games

CityTresure can be described as a very simple augmented reality team-based city game that supports informal learning.

Game indicates a set of rigid structures – namely, rules – that generate a game space which players enter for pleasure (Salen & Zimmermann, 2004; Betrus & Botturi, in press). Rules not only define allowed moves, but also establish the goal for which players compete or collaborate. As Huizinga (1955) put it, games are

a voluntary activity or occupation executed within certain fixed limits of time and place, according to rules freely accepted but absolutely binding, having its aim in itself and accompanied by a feeling of tension, joy and the consciousness that it is ‘different’ from ‘ordinary life’ (p. 28).

Games like soccer, poker, pool, or Stratego can fit this definition, but at its core, playing describes a child’s activity of exploring the world, and of learning (Sutton-Smith, 1979). Gee (2003) emphasizes that games promote a critical and active way of learning, and it is not by chance that playing is the primary learning modality for human beings: from 0 to 5 years, children learn about themselves and about the world through playing.

Playing always entails learning: learning the rules, learning a new strategy, learning how to beat the opponent or the system (Botturi & Loh, 2008). This is why games and videogames have such a powerful learning power (Gee, 2003) and why they have always been part, in different forms, of the Western educational tradition (Betrus & Botturi, in press).

From the perspective of educators, games can be used to foster learning in different ways (Betrus & Botturi, in press): games and videogames (a) increase motivation; (b) support complex understanding; (c) allow reflective learning; and (d) provide constant feedback that allows self-regulation. Why is it so? Basically, while classrooms need students, games need players. Unlike students who follow teachers in class activities, players are the actual engine of a game: if a student does not pay attention, he doesn’t learn, but the activity goes on; on the contrary, if a player does not move, nothing happens in a game (Prensky, 2006). Playing means to be a protagonist, and learning becomes a “natural” thing to do for winning. In other words, learning is situated.

Of course, not all games are alike, and different games should be used for different purposes. For example, games based on digital technologies (videogames, but also mobile games or Internet-based, occasionally Flash, games) can support complex rule systems managed by the machine, so that they can embed simulations. Digital technologies also allow the development of mobile games that enrich real locations with digital content delivered through mobile (possibly location-aware) devices. Also, digital games are appealing to digital natives (Prensky, 2001), just because of their media.

City games can be considered a subset of so-called pervasive games, where the game experience is extended into the real world thanks to mobile technologies, and changes according to (1) the players’ position within the context, and (2) the players’ actions (Benford, et al., 2005). In city games, the issue of context (i.e. territory) awareness and the issue of getting the right information (from the territory) in order to fulfil the games’ requirements is crucial. As these games are location-dependent, in the literature they have been also called location-based games. Nicklas, Pfisterer and Mitschang (2001) emphasize that players move around the real world and interact with the game by changing their position and visiting certain places that are of interest to the game.

In the last years, location-aware and pervasive games have been quite successful both in academic and professional fields, achieving the status of new outdoor technological entertainment (Han et al., 2005). Games such as Geocaching (Webb, 2001), Can You See Me Now? (Flintham et al., 2003) and Human Pacman (Cheok, et al., 2003) had – and still have – many followers in different countries around the world.

Besides, some companies are massively promoting marketing initiatives related to this kind of game; for instance, Pepsi Co. with the game Pepsi Foot (Diercks, 2001).

The learning potential of location-based games comes from connecting technology and real spaces and objects. Educational location-based games have been implemented for several purposes, from nature and science learning in wood camps (Mistery Trip; Martin, 2008), to history and business finance (Dow Day and Hip Hop Tycoon, presented at http://lgl.gameslearningsociety.org).

Nicklas, Pfisterer and Mitschang (2001) classified location-based games in three categories, depending on the degree of dependence on specific location-related information:

- Mobile games: the game does not need to track the players’ position. Proximity sensing and local communication are sufficient in order to generate location-based interactions.

- Location-aware games: the geographical position of the players matters and is tracked by the system. The game experience is fully related to the location the player is visiting.

- Spatially aware games: the surrounding objects are part of the game. Game interactions can be connected to objects and specific spaces.

CityTreasure, presented in the following section, can be considered as a location-aware game, where the interaction with the geographical location of the players matters in order to achieve the goals of the game.

Informal learning

By their very nature, games cannot be formal. Indeed, somebody who is obliged to play a game cannot be really said to be playing (or having fun! Cfr. Botturi & Loh, 2008). Games, in any form, foster informal learning.

Rogers defines informal learning as

all the incidental learning, unstructured, unpurposeful but the most extensive and most important part of all the learning that all of us do everyday of our lives (Rogers, 2004).

Informal learning has been studied mainly in relation to job skills, in the domain of vocational training and workplace studies (Garrick, 1998; Hager, 1998). Tourism, and cultural tourism in particular, is another relevant area for informal learning, as it offers a rich experiential context where people learn about culture, art, and history (Inversini & Cantoni, 2008). Blending cultural and touristic informal learning with games was the challenge of eTreasure, the source project of CityTreasure.

eTreasure also dealt with the so-called economy of attention (Davenport and Beck, 2001). Attention is actually a scarce resource and for this reason nowadays is treated as an economic element (Iskold, 2007; Falkinger, 2007). eTreasure and CityTreasure were deigned to help tourists and students to visit a given place focusing their attention first on a specific issue (e.g., the cultural heritage field), and secondly on a particular aspect (e.g., the author of a fresco). Framed within the compelling context of a game, directed attention provides a strong basis for starting an informal learning process.

CityTreasure

This section presents the CityTreasure system in two aspects: the mobile technologies used and the design of the system and of its content.

Technologies

CityTreasure was born out of the experience of eTreasure, a mobile game-based platform for tourists (Cantoni, Inversini & Rega, 2008). The system was originally developed, and then adapted to use with schools, by the NewMinE Lab of the Università della Svizzera italiana (USI) in Lugano, Switzerland, in collaboration with Orange Switzerland as technological partner.

eTreasure is a digital treasure hunt engine that can support any number of paths and locations. Players can interact with the system with any GSM mobile device using SMS (Short Message System) messages. SMS were chosen because (a) they are among the easiest ways of using a cell phone; (b) the cell phone is widely used and perceived as something deeply private, at the same time being a sort of communication hub; and (c) SMS systems can be easily extended to integrate more text and other media through MMS (Multimedia Message System).

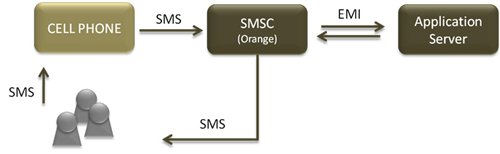

The system is composed of two layers (Figure 1).

- The first layer is devoted to SMS routing, and is provided and hosted by the technological partner (Orange Switzerland). The SMS routing server is called SMSC (Short Message Service Centre) and operates as a hub for sending SMS messages to the right player. The interface used for the communication with the application server is called EMI (External Machine Interface).

- The second layer is the application server where all the technology related to the application is hosted: the database with content, and the software that keeps track of the position of players within the treasure hunt path, composing the next message to each of them based on their answers. The application server also stores timestamps and results for each player action, and generates user statistics.

Fig 1: The eTreasure/CityTreasure System.

Game design and content development

Groups of students participating in CityTreasure are competing with each other in order to win the game. Different from normal treasure hunts, where the fastest wins, CityTreasure is based on score: the best observers of the city and of its cultural heritage win. In order to understand the actual design of the system and of the content, the game dynamic should be illustrated first.

The sparkle of the game is competition among groups of students, each equipped with a city map and a cell phone. Through the cell phone, the system tells students to locate a spot on the map (a Point of Interest, PoI), and asks them a question about it. Students have to find it on the map, walk to it, and find the solution to the riddle (Figure 2). The system then asks two more riddles (3 in total for each PoI) before indicating another location on the map. The system assigns 5 points for each correct answer, and 0 for each wrong answer. At the end of the treasure hunt, composed of 4 or 5 PoIs, the system sends a message with the final score of the group. The group with the highest score wins.

Fig 2: Hint and riddle

While the design of the game is straightforward, the development of content presented some critical issues. Indeed, content is the key feature that can make the playing experience aligned with the actual learning goals of the field trip. Content is what can make an application like CityTreasure a real informal learning application and not just a funny gadget.

Content development was carried out within the eLearning Lab of the Master in Technology Enhanced Communication for Cultural Heritage (TEC-CH) at USI, led by the first author of this paper, in collaboration with four primary school teachers. The process followed four steps:

- selecting relevant PoIs. This was done following two criteria: (a) including locations that are usually included in school field trip plans, and (b) including locations with similar relative distance from each other, so that randomly selected paths would have more or less the same length. PoIs included both artistic sites (churches, monuments, etc.) and civil sites (the town hall, important commercial streets, etc.).

- developing riddles for each PoI. In order to allow diversity and prevent the “spread-the-news” effect among the groups, 5 riddles were developed for each PoI. This was done by TEC-CH students, based on instructional materials that teachers provided. Teachers then revised riddles and answers to ensure alignment with instructional goals.

- preparing the content for the system. Riddles had to be phrased to stay within the limit of characters allowed by SMS standards, and all possible correct variations for answers (e.g., spelling variants, number vs. text variants, etc.) had to be identified and coded.

- feeding the content into the application server, which was managed by the technical staff at NewMinE Lab.

A group of expert users (i.e., not children) was asked to test the game, and the content was consequently refined based on the feedback collected. Also, a test micro-treasure hunt, with just one riddle, was developed in order to allow new users to test the system before actually starting the game.

The good thing about teaching is that, as in acting, the script is only part of the show. In the same way, the technological architecture and the content developed only represent the “toy” of CityTreasure. The actual game experience is broader, and includes many non-technological details that can make a difference. Indeed, the best technology itself does not guarantee any positive learning outcome. The CityTreasure team therefore focused on designing the whole experience for the treasure hunt. This included:

- The development of a paper-based teacher guide that instructed teachers about preparation for the activity (including setting the right expectations, and providing required previous knowledge and skills, such as being able to read the city map);

- The selection of a proper meeting place for the start of the game, and of an adequate ending place with respect to the location of the school (or of the train station, for those coming from out of town);

- A 1-hour briefing with involved teachers in order to arrange details for individual cases, and for instructing them on the use of the guide, and on how to involve collaborators (other teachers or parents).

Children Hunting for Treasure In Lugano

During May and June 2008, 4 primary school classes (about 20 students per class) and 4 secondary school classes (about 20 students per class), for a total of over 150 children, played the treasure hunt with CityTreasure as part of their field trip to Lugano (Figure 3).

The general learning goals proposed by teachers for the use of CityTreasure were the following: (a) fostering the observation of details in cultural heritage and stimulating meaningful learning; (b) enhancing team-work attitudes and skills; and (c) making the learning of history, geography and fine arts fun and worth remembering in connection with cultural heritage locations.

Fig. 3: Children playing CityTreasure

As already mentioned, teachers involved students in preparation activities before the actual game-playing sessions. Students were therefore aware that they would be playing a game, and had already practised the basic skills required for the game, including map-reading and following general behavior rules for cities (such as street crossing, etc.). Teachers also read the guide that previewed all PoIs, riddles and answers, so that they could provide background information and connect the activity to their program. The same guide (without solutions to riddles, though) was given to other support teachers or parents who helped with the field trip (each of the primary school groups was accompanied by a parent volunteering).

Classes gathered at the selected starting point, and the game was presented by a staff member of USI. After hearing the basic rules of the game, each group was given a cell phone (private cell phones are prohibited in most schools) and the test 1-riddle treasure hunt was run, in order to test interaction with the system. Groups were also given an info sheet that summarized the rules and clearly indicated the time limit and the final meeting point. The game was then started, and groups dashed away to their first locations (actually, time was not relevant for the game, but this did not prevent children from running as fast as they could from one PoI to the next).

During the game, two forms of control were put in place in order to ensure both safety and smooth progress. One person was monitoring groups from the interface of the application server. In this way he was able to see their next location, and to see if progress was adequate for the time available. Another staff member rode through the city on a bike, providing support to lost or late groups, and also collecting their first-hand feedback. A staff member was also present at the last PoI (the end place), for collecting cell phones and feedback. Teachers provided a wrap-up and small “prize ceremony”.

While this was rather structured and resource-consuming organization, it was set up to provide a consistent and carefully controlled experience - paramount in the first field test of the application. It is surely possible to allow more independent use of CityTreasure; however, experience so far indicates that the “context” is key for success – actually, the application can be a catalyst that builds upon, rather than substitutes for, a well-managed field trip.

Evaluation

The evaluation was both formative, i.e., concerning learning outcomes, and confirmative, i.e., aimed at identifying improvements needed both in the system and in the overall experience. The evaluation was based on three data sources:

- Participant observation by staff members, who reported on activities and took pictures during the experience;

- A survey handed out to all adults (teachers and parents) at the end of the experience. Surveys were collected both for secondary schools (N=7 for 4 classes) and primary schools (N=16 for 4 classes)

- An interview with teachers at the end of the experience

Added to these was an indirect measure of learning outcomes as reported by teachers.

The assessment of learning outcomes by teachers was extremely positive: all of them reported that the treasure hunt met their expectations in terms of students gaining knowledge about cultural heritage and other relevant locations.

The engagement of children, on the other hand, was more than expected. Indeed, the school trip was a memorable adventure and a topic for discussion at home. Engagement is difficult to define, and was pragmatically measured through a set of three correlated indicators from the survey: a measurement of fun as perceived by adults on a likert scale, a similar measurement of interest, and an open field for a single adjective to describe the overall attitude of students during the treasure hunt. This was balanced by another question (also on a likert scale) asking how hard the treasure hunt was for the students: balance was indeed a concern during the design of CityTreasure, an activity that demanded about 45 minutes of walking through the city center. Figure 4 reports the results of the measurement of engagement for primary and secondary school classes (values are on a scale from 1 to 10; please notice that the measurement of hardness used an inverted scale, 10 meaning students were not tired). The difference in evaluation between secondary and primary schools will be addressed later.

Fig 4: Engagement

To confirm such high assessment, the most-used adjective for describing students during the treasure hunt was “enthusiastic” (9 occurrences), followed by “happy” (3 occurrences), then by “engaged”, “interested”, “satisfied” and “tired” (1 occurrence).

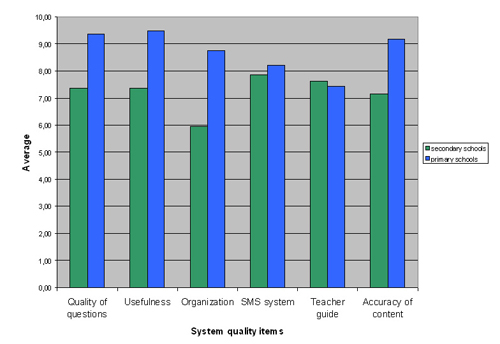

The survey also aimed at assessing the quality of the system. Survey items asked participants to rate on a likert scale the following features: quality of questions, usefulness, organization (i.e., logistics, time management, etc.), the SMS system, the teacher guide, the accuracy of content. Results are shown in Figure 5.

Fig 5: System quality assessment results

Indeed, all the components of the system received high marks. The lowest mark was assigned to the teacher guide and to the SMS system (which actually suffered from overload at the start of the game, when all groups sent a message simultaneously; also, some children found it difficult to write SMS message with devices different form the ones they were used to). The organization, despite the great effort in preparation, was assessed with marks a little lower than the content. This can be interpreted as the effect of a general loss of control by teachers on the activity – indeed a common effect in game-based learning (Betrus & Botturi, in press).

The difference in performance between secondary and primary school is evident. Actually, both schools got the same assistance and used the same content (except that secondary schools had 1 additional PoI in their paths). The main difference was in the role that teachers took during the game: secondary school groups were not accompanied by adults, and the students never met adults during the game. This resulted in less focus on the game (some groups stopped for an ice cream…), longer time to the end (about 1.5 times the time spent by primary school children on the same path), and less satisfaction. This confirms the claim that effective game-based experiences require guidance from teachers (Betrus & Botturi, 2008; Squire & Jenkins, 2004)

Conclusions & Further Work

CityTreasure is a mobile application for supporting location-based game experiences for schools. It is a simple idea and a simple technological application. The fun of it, and its learning power, comes from competition among the groups of students and, of course, from the use of mobile technologies which have deep penetration in that age group and are usually forbidden at school.

The key points for the success of the application were careful development of content, in association with teachers, and detailed design of the experience, as opposed to the application alone. Evaluation results indicated successful implementation, where differences can be traced back exactly to the care in the details outside the technological application (i.e., the role and presence of adult guidance in the game).

eTreasure is also developing an on-line community of players. The community will be a place where players of different treasure hunt games can meet on-line and share opinions and pictures of Lugano.

The major plan regarding the improvement of the treasure hunt management software is toprovide the opportunity to create a kind of personal treasure hunt on-line, enrolling players and allowing them to advertise it. The “creators” wizard is now in alpha testing at USI.

Acknowledgements

This project was developed thanks to the support of Orange Switzerland and the School Council of the City of Lugano.

References

Benford, S., C. Magerkurth, & P. Ljungstrand (2005). Bridging the physical and digital in pervasive gaming. Communications of the ACM, 48(3), 54-57.

Betrus, A. K. & L. Botturi, L. (in press). Principles of Using Simulations and Games for Teaching. In A. Hirumi (ed.) Playing Games in Schools: Engaging Learners through Interactive Entertainment. International Society for Technology in Education.

Botturi, L. & C.S. Loh (2009). Once Upon a Game: Rediscovering the Roots of Games in Education. In C. T. Miller (ed.), Games: purpose and potential in education. New York: Springer.

Cantoni, L., A. Inversini, I. Rega (2008). eTreasure: Promoting Informal Learning in the Tourism Field Through an SMS-Based Treasure Hunt. Proceedings of EDmedia 2008. Vienna, Austria.

Cheok, A. D., S.W. Fong, K.H. Goh, X. Yang, W. Liu, & F. Farzbiz (2003). Human pacman: A sensing-based mobile entertainment system with ubiquitous computing and tangible interaction. Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Network and System Support for Games, 106-117.

Davenport, T. H., & J. C. Beck (2001). The Attention Economy: Understanding the New Currency of Business. Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA.

Diercks, R. (2001). “Mobile advertising: Not as bad as you think”. Wireless Internet Mag, July-Aug.

Garrick, J. (1998). Informal Learning in the Workplace: Unmasking Human Resource Development. London: Routledge

Gee, J. P. (2003). What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy. New York: Palgrave/Macmillan.

Falkinger, J. (2007). “Attention economies”. Journal of Economic Theory, 133, 266-294

Flintham, M., S.Benford, R. Anastasi, T. Hemmings, A. Crabtree, C. Greenhalgh, T. Rodden, N. Tandavanitj, M. Adams, & J. Row-Farr (2003). “Where on-line meets on the streets: Experiences with mobile mixed reality games”. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 569-576.

Hager, P. (1998). “Recognition of informal learning: challenges and issues”. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 50(4), 521-535.

Han, S. Y., M.K. Cho, & M.K. Choi (2005). “Ubitem: A framework for interactive marketing in location-based gaming environment”. Fourth International Conference on Mobile Business (mBusiness), Sydney, 11 103-108.

Huizinga, J.(1955) [1938]. Homo Ludens. A study of the play-element in culture. Boston: Beacon Press.

Iskold, A.(2007). The Attention Economy: An Overview. ReadWriteWeb. Retrieved on January 13th, 2009 from http://www.readwriteweb.com/archives/attention_economy_overview.php

Martin, J.(2008). Making Video Games in the Woods: An Unlikely Partnership Connects Kids to Their Environment. Presented at American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting. New York, March 24-29.

Nicklas, D., C. Pfisterer, & B. Mitschang (2001). “Towards location-based games”. Proceedings of the International Conference on Applications and Development of Computer Games in the 21st Century: ADCOG, 21 61-67.

Prensky (2006). Don’t Bother Me Mom—I’m Learning. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House.

Prensky, M.(2001). On the Horizon. 9(5), 1-2. MCB University Press.

Rogers, A.(2004). Looking again at non-formal and informal education - towards a new paradigm. The Encyclopaedia of Informal Education. Retrieved on January 13th, 2009 from www.infed.org/biblio/non_formal_paradigm.htm.

Salen, K. & E. Zimmerman (2004). Rules of Play. Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The MIT Press.

Squire, K. & H. Jenkins (2004). “Harnessing the power of games in education”. Insight, 3(1), 5-33.

Sutton-Smith, B. (1979). Play and Learning. New York: Gardner Press.

Webb, R. M. (2001). “Recreational Geocaching: The Southeast Queensland experience”. In A Spatial Odyssey, Australian Surveyors Congress [September].