The Mobile Web is Coming to a Museum Near You

Various researchers project that mobile devices will become commonplace in the next few years, penetrating markets all over the world. According to Nielsen (Stewart, 2009), smartphone sales are expected to lead the way, accounting for nearly half of worldwide sales by 2013. In the US alone, the number of smartphone subscribers during the 2008-2009 Q2 period increased by 72%, or 26.1 million users.

Fig 1: Smartphone sales are going through the roof

Given the growth in smartphone sales and their penetration rate worldwide, it is clear that museums must confront the challenges and opportunities presented by the mobile Web. Museum visitors can increasingly be expected to arrive carrying networked mobile devices equipped to access the Web. Museums no longer need be in the business of renting and maintaining handsets for audio tours - they can provide access to audio, visual, and other complementary content via the visitors’ own handheld devices.

Forward-looking museums will embrace this trend and begin to provide supplemental content that enhances their visitors’ in-museum experience. Switching to the Internet as a vehicle for in-house content delivery provides a tremendous opportunity for museums to establish ongoing relationships with visitors and allows visitors to share and promote museum content and experiences via their personal social networks.

This is not to say that all museum visitors will have cell phones or other digital mobile devices (like iPod touch and iPad). They won’t, and the percentage that doesn’t have such mobile devices will vary from museum to museum, depending on the geographic location and demographics of the visitors. Museums will also differ on how much they are bothered by this fact, and whether they consider this differential to constitute an unacceptable digital divide. We’ll leave that issue to the individual museums. But let’s also keep in mind that not every museum visitor has an extra seven dollars to rent an audio guide. And not every museum has the money to buy them.

Let’s also acknowledge up front that not everybody is going to want to use a mobile device in a museum, no matter what content or activities it enables. Many people visit museums with friends as a way of spending time together; others go to commune with art; still others may have a pair of wayward toddlers on their hands and can’t take their eyes off them for a moment.

At the same time, we have all observed that there is no shortage of visitors engaged with props and gadgets of various sorts, including (notoriously) cameras and cell phones, but also audio tour guides and printed museum guides. These visitors are all using technology (in the widest sense) to capture, share and enrich aspects of their museum visit. And these visitors are all likely candidates for helping the museum share and promote its content.

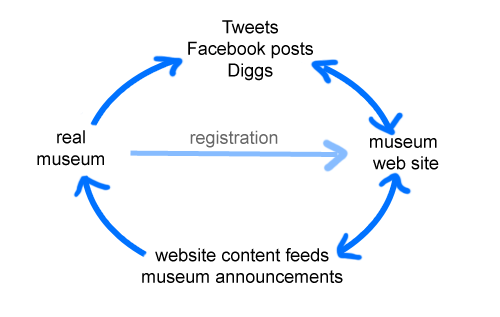

Open Museum has undertaken to meet this challenge by creating a new service, Mobeum, which takes advantage of the museum visitors’ smartphones to tie together their gallery and Web experiences and inspire and permit visitors to share museum Web content via the Web. This gallery-mobile-Web connection has the potential to set up what we call a digital outreach viral loop. The digital outreach viral loop uses aspects of both viral marketing and permission marketing to draw new visitors to the museum’s Web site, and more importantly, to encourage new and return visits to the physical museum itself.

Viral Marketing and Permission Marketing

Most Internet-based marketing today can be thought of as depending, to differing degrees, on the two related but distinct concepts of permission marketing and viral marketing.

Seth Godin (1999) introduced the term permission marketing to describe what he considered the basis for a more effective relationship with customers. Essentially, marketers obtain permission from customers to deliver information that the customers want and appreciate. A classic example is a Facebook user electing to become a fan of a museum and receiving updates from the museum in a Facebook news feed.

The term viral marketing emerged in the mid-nineties to describe the transmission of advertising messages passed (usually voluntarily) from individual to individual. Because each individual can pass the message on to multiple recipients, viral marketing permits the audience to grow exponentially when the viral message is especially compelling.

Generally speaking, when museums create presences on Facebook, or tweet about museum events, they are hoping to increase the reach of their permission marketing audience by having the audience virally promote museum content and feeds. This can happen either actively (e.g. when a follower retweets) or passively (when a museum shows up and is noticed in a Facebook friend’s activity list.)

The exponential potential of viral marketing is responsible for its high profile, but marketers have long appreciated word of mouth recommendations at least as much for their effectiveness. When a museum tells you “we have a great exhibition”, it may be interesting, but when your best friend tells you not to miss it, it’s truly compelling.

The challenge for museums is to find effective ways to get their visitors to tell their friends about what’s happening in the museum and invite them to check it out. Hopefully those friends will in turn give the museum permission to continue the relationship. The relationship is established virally and consolidated by permission. This scenario presupposes specific, accessible mechanisms for both viral transmission and permission-based continuation.

The Digital Outreach Viral Loop

In a nutshell, the digital outreach viral loop depends on getting museum visitors (and museum Web site visitors) to share museum objects with their social network via tweets, SMS messages, Facebook status updates, Digg, and the like. Those messages contain links to the museum Web site where the new visitors are invited to establish permission-based on-line relationships (e.g., register or subscribe to syndicated notifications) and are invited to visit the physical museum. New members are in turn provided with opportunities to share their content with their social networks.

Fig 2: The Digital Outreach Viral Loop

This should all sound fairly familiar, and, as we all know, the “only” problem is getting the visitors to subscribe, return, and tweet. The main difference between the schema outlined here and the typical Web site viral promotion cycle is that it includes an added scenario whereby the visitor encounters and shares museum content directly from the gallery floor using a mobile browser.

Why Gallery Tours?

So why do we think gallery tours constitute such a significant opportunity for museums?

Because the kernel of the museum experience is the experience the museum visitor has at the museum.

If we want our visitors to have a “hey, this is really cool, I want to share it with my friends” moment, we particularly want them to have it at the museum. To the extent that we believe in the primacy of the object on display, we expect them to have it at the museum. If they have it on-line, then we hope it will propel them to the museum itself, where they can have it in spades. And if they are moved to share it with their friends, we hope their friends experience it, ultimately, by coming to the museum themselves.

This is not to say that the content that museums put on the Web doesn’t have any intrinsic value or that there aren’t circumstances where the Web version isn’t more convenient, or more accessible than the physical museum. Certain activities (like leaving a question for a curator) may even be better suited to the Web.

But we have to remember that museums have no distinct competitive advantage as Web site content producers. The ultimate value of the museum lies in its physical presence, its collections, exhibits, visitors, staff, and community.

None of those can be purely virtual. To the extent that the museum’s activities don’t depend upon the museums physical presence and physical community, they could be more cost effectively delivered by an institution unencumbered by those physical ‘assets’.

By making additional content available to the visitors on the gallery floor, we can enhance their immediate experience, and we can provide them with a tool that allows them - at the point of maximal enthusiasm - to bookmark and share that content with others.

Fig 3: Shared Open Museum objects on Facebook and Twitter

A gallery tour that doesn’t allow visitors to share content is a lost opportunity, not just for the museum, but for the visitor.

Creating the Conditions of Possibility for Viral Loops

The ability to share the experience of museum objects via social networks depends upon some architectural and other preconditions.

Consider a museum visitor confronted with a compelling object, or with some engaging complementary content concerning the object (say, a juicy piece of gossip about Pablo Picasso.) What would it take for them to be able to share it with their friends, and have their friends in turn share it with their friends, in the process, acquainting all with the sponsoring museum, and providing all with the opportunity to establish with that museum an ongoing relationship that might ultimately be converted to a ‘real’ museum visit?

- Need Mobile and Standard versions of all content - The content must be packaged as a shareable bundle of content. Ordinarily this would mean a URL pointing at a representation of the object or content tidbit accessible to the person or people they are sending it to. Every URL sent out has to have comparable mobile and standard versions, and the page has to resolve to the same content on either style of browser. (This is not as common as you might think. Lots of Web sites redirect URLs to a mobile page that doesn’t contain the same content that the referring standard URL pointed to.)

- Have to be able to ‘acquire’ the viewer - The link has to resolve to a context in which permission to continue the relationship can be acquired from the receiving party. Just sending out a link to a YouTube video will take the recipient to YouTube - great for YouTube, but less than perfect for the museum. It would be better to send viewers to a page on the museum Web site where they can watch the same embedded video - and subscribe to museum announcements of additional content, etc. You certainly won’t get permission from every visitor, and you probably won’t get permission from many visitors the first time. But you want to make sure that after they have turned up on your site a few times, and found it valuable, they can elect to continue the relationship.

- Has to be virally re-sharable - The link has to resolve to a context in which the recipients can easily re-share the link if they find it compelling, and the re-shared link has to retain the context of the original wrapper. The recipients should be able to send the link on to friends in more or less the same form that they received it. This transmissibility of the object is a precondition of viral transmission.

- Need announcements and invitations - Once the Web visitor gives the museum permission to communicate, the museum has to be able to periodically propose opportunities that motivate actual visits to the museum.

Viral Architecture: Objects as Thick Social Atoms

The transmissibility (viral re-sharability) of an object is a precondition of the digital outreach loop. It presupposes that it is possible to view, send, share the social object from either a desktop or mobile browser and that both experiences will be fully satisfying. In Open Museum, transmissibility is made possible through objects conceptualized and created as thick social atoms.

Our design philosophy at Open Museum is object-centered. Our architecture is based on objects, people, and museums, with objects playing the primary mediating role between people (including visitors, curators, and artists) and museums.

What do we mean when we say that objects are thick social atoms?

Thick objects are structured clusters of content with multiple pages (or facets) containing images, text, audio, video, geocoded location, tags, and comments.

Social objects are designed to be shared and to form the focus of social interactions. Visitors can tag and bookmark (favorite) objects, comment on their content, see who else likes them, and easily share links to them using Facebook, twitter, and other social networking services.

Objects are atoms in the sense that a pointer to an object is recognized as such in any Open Museum context. A link to an object resolves to the same content (formatted appropriately) on desktop browsers, on mobile devices, and in the mobile tour interface.

Our theory was that this object-centered approach could be used as the basis for the design of a museum mobile tour service: a Web-based mobile tour service with an architecture supporting the combination of viral and permission marketing referred to here as the digital outreach viral loop.

Overview of the Mobile Tour Project at the Hood

Our mobile tour test partner was the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College. The test site was the European Art collection on display in the Albright Gallery. The Gallery contains roughly 30 paintings and sculptures from the renaissance to the early modern era.

With the assistance of the curatorial staff, we created an Open Museum collection containing most of the objects on display in the gallery, with the exception of a few works (e.g. a cubist painting by Picasso) still under copyright. To arrive rapidly at a testable pilot using resources provided by the Hood, we wrote transcripts and recorded them in MP3 format to upload to Open Museum. We also created additional pages of information with details, history, composition, in order to create thick objects which would present visitors with additional related content during their gallery tours. (The supplemental content, created for testing purposes from public domain sources and only loosely fact-checked, is not visible on the public Web site.)

The initial collection comprised 23 objects, each one with a high-resolution image, label information, explanatory text drawn mainly from the printed museum catalogue, and a short (2-3 minute) audio on a theme intended to assist visitors in experiencing the work in person.

During the month of January 2010, we conducted two formal tests on-site in the Albright Gallery at the Hood, as well as many additional informal iterations of the design-build-test cycle.

Our initial design was based on a simple mobile adaptation of the standard site. As a result of our first formal test, we discovered that our initial approach and architecture were seriously flawed. The rich feature set needed for browsing the whole Open Museum Web site on a mobile browser is simply too divergent from the simple and streamlined interface required for effortless navigation by first-time users within the physical exhibit.

We concluded that we also needed a dedicated mobile tour designed specifically for use inside the museum. As a result, we went back to the drawing board and implemented a dedicated mobile tour service which we call Mobeum. The mobile tour shares the same back end server with the same social objects as the mobile and desktop versions of Open Museum, but it presents a different interface with a different set of navigational tools for getting from one object to the next.

To show you how we reached this conclusion, and what it entailed, we share the Hood Mobeum case study.

Version 1: Omobi - A mobile version of Open Museum

Our first approach to supporting in-museum access to supplemental content was to create a mobile version of Open Museum. The system was based on the assumption that it would suffice to simply assist visitors in navigating through the Open Museum mobile browser to the European Collection.

Our strategy was to create a parallel (slightly stripped down) interface to Open Museum content. Every major page in Open Museum had a corresponding page (or set of pages) in the mobile version. There was a main page for each museum, a page for each collection in the museum, a page for each object in the collections, and supplemental pages with additional content, comment threads, etc. This result was a mobile site with a fairly conventional drill-down architecture with lists of sub-content for each content node.

Fig 4: Omobi: the first version of Open Museum’s mobile museum tour

The object page presented a thumbnail image and basic label information about the image, as well as a menu of links to audio, video, and supplemental detail pages for that object. Clicking on an audio link automatically began playing the audio guide. When the audio was finished, the browser automatically returned to the object page. Users could further explore the object, share the object via a social bookmarking service like Digg, and make a post to Facebook or tweet.

The site was easy enough to navigate if you grasped the underlying Web site architecture but bore little resemblance to the physical layout of the objects in the physical exhibit.

We provided two additional navigational facilities to support in-gallery navigation:

- Short numeric codes (called quick codes) corresponding to individual objects and collections that could be looked up quickly. The quick codes were listed on the label and users could look them up by entering them into a text box in their mobile browsers. (Quick code lookup is similar to the way individual audio segments can be located using a dedicated audio guide.)

- QD codes (2-D bar codes) encoding the URL of the page of the object or collection. If users had a barcode reader installed in their phone, they could point the phone’s camera at the bar code, press a button, and be taken to the appropriate page in their mobile browser.

The curatorial interface automatically generated both Quick and QR codes to be printed on the object labels in the museum.

This translation, if you will, of the standard Open Museum Web site to mobile browser view was the first version we tested.

First Test Experience & Survey Results

To prepare for the test, we printed out labels for each object with automatically generated QR code and Quick-codes, and set them on the ground in front of each panel, and created an introductory panel that provided three options for joining the collection: URL, SMS, or QR code.

The test group consisted of nine Dartmouth college undergraduates enrolled in a museum seminar, all of them women, half of them using a smartphone (three Blackberry, one ipod, two borrowing an ipod to repeat the test). Participants were asked to read the introductory panel and then try to use their cell phones to take the tour. No additional instructions were given beyond the warning that this was alpha software and that they should just plow ahead unless something was obviously broken, or they got totally stuck.

Fig 5: First test of Open Museum’s mobile museum tour at the Hood

On the whole, participants said the mobile tour had great potential to enrich visitor experience, but there were issues that needed to be addressed. These issues fell into three categories: intrusiveness of sound, ease of use, and quality of content.

| Ease of Use 1 (low) - 10 |

ipod touch | Samsung | Samsung | Black berry |

Black berry |

Samsung | iPhone | LG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Getting started | 7 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 7.5 | 1 |

| Viewing museums | 8 | 10 | 9 | 5 | 8.5 | 4 | ||

| Viewing collections | 8 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 8.5 | 5 | ||

| Audio Guide | 9 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 8.5 | 5 | ||

| Signing in | 9 | 6 | 7 | 1 | ||||

| Navigation bar/ icons | 6 | 7 | 2 | 5.5 | 3 | |||

| Help/ ? | 8 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 4 | |||

| Search | 8 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 4 | |||

| Favorite object | 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Look & Feel | 9 | 7 | 7 | 6 | ||||

| arrive | URL | SMS | URL | SMS | URL | SMS, QR, URL | ||

| navigate | code/ search | search | search | code | search, QR | |||

| registered | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes |

| friend Hood | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes |

| text message | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | yes |

| browse | yes | NA | NA | yes | yes | no | yes | no |

| other mobile | regular cell | 0 | 0 | ipod touch | 0 | laptop | ||

| next mobile | regular cell | Black berry |

unsure | Black berry |

0 | iPhone | Black berry |

Table 1: Results from first test of Open Museum’s mobile museum tour at the Hood

What many participants liked about the Web-based mobile tour was the possibility of listening to (as well as seeing and reading) pertinent information while in the gallery, and the visitor-driven pace and content. Most were happy to be liberated from reading labels and were interested in having the ability to search for additional information at will. The kind of information they wanted to access included related works, other works by the same artist, point and counterpoint discussions by specialists, and gossip about the piece. They wanted this information to be high quality, clear and easily accessible. They wanted these enrichments while preserving the traditional quiet and tranquility of the gallery experience.

The first point, the intrusiveness of audio guides, was a problem, but one easily solved with earphones. With earphones, a tool most young mobile users carry and which a gallery can distribute for under $1.00 per pair, cut the noise and allow the listeners to lower their device out of the line of sight.

The second critique, ease of use, was more complicated. Contrary to our assumption, mobile tour users did not want the full feature set of the mobile browser. They wanted a streamlined interface that, while supporting access to supplemental material, also provided a dead simple “next” button. As one participant states, “While in the gallery no one wants to be fiddling with a device. If it’s not self-evident, I won’t take the time to use it.”

Testers were intrigued by the QR code concept, but every tester got bogged down in trying to understand what a QR code reader was and whether or not their phone had one. Although we hadn’t provided any written instructions on how to download a QR reader app, one sophisticated iPhone user bought one for $1.99 and tried it out. She was wowed by the technology, but questioned its utility, given that the application had no other obvious use to her and she could get to the Open Museum objects and collection just as easily via other methods. Although very cool and in keeping with future trends, it was clear that the QR code should be removed from object labels and deemphasized on the introductory panel.

We were interested to find that most people seemed to assume that there was a "right" order in which to view the objects, and they were happy to follow in that order when "on the tour." This insight led us to the conclusion that we needed to develop a dedicated mobile version of the standard site rather than repurpose the mobile Web version.

Version 2: Mobeum - A Dedicated Mobile Tour Interface

As a result of the feedback, we created a separate mobile tour service called Mobeum. Mobeum shares the same back end as the standard and mobile Open Museum browsers, but presents a completely different user interface (one that is more tour-like). There is much less on the screen, and navigation options have been reduced to forward, back and # code lookup. Once at an object page, however, a visitor still has options for audio and more information in the form of image, text, audio and video.

Fig 6: Mobeum: the second version of Open Museum’s mobile museum tour

We also made changes to the content management features available in the curators’ interface. (Curating is only possible from the desktop version of Open Museum.) In order to support dedicated tours, we implemented the new concept of a content playlist containing both museum objects and tour-specific signboards appropriate to the gallery context. From the content perspective, Mobeum tours are simply ordered playlists containing both objects (bundled together with their full set of multi-media information) and customized tour-only panels (providing an orientation to Mobeum and overview of the collection featured in the tour).

Fig 7: Mobeum curatorial interface in standard browser view (Open Museum)

The objects in the mobile tour can be arranged independently of their order in the desktop and mobile browser collection. Objects can be removed from the tour playlist without being removed from the collection, and objects from multiple collections can be combined in a single tour.

Signboards permit the addition of pages contain text, images, audio, or embedded vide that don’t correspond to an individual object in the collection. For instance, a tour welcome page with a recorded greeting from the museum director, or a description of the physical surroundings of the gallery itself.

(By creating signboards, we temporarily broke our rule that all content must have analogs in both mobile and desktop versions. We are planning to add the ability to view tours from the desktop in the near future, at which point the mobile and desktop version will once more be fully synchronized.)

Second Test

Fig 8: Second test of Open Museum’s mobile tour (Mobeum) at the Hood

After implementing these changes, we launched Mobeum and ran a second test at the Hood. The test group was smaller (three adult members of the Dartmouth community); this in practice made it possible to keep an eye on what everybody was doing, rather than having to rely on the feedback from the user questionnaires. As Steve Krug (2006) observes, there is not much benefit in doing usability testing on more than three or four users per iteration since they’ll find most of the significant problems anyway.

Their feedback suggests that we succeeded in simplifying the Mobeum interface. Everyone concurred that the user interface was simple and not a barrier to use.

| Ease of Use 1(low) - 10 | iPhone | iPhone | iPhone borrowed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connection to Hood | 7 | 9 | 5 |

| Find Tour | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| View Object | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| View More of Object | 5 | 9 | 10 |

| Go to Next Object | 9 | 10 | |

| Audio Guide | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| Go to Photo/ Enlarge | 8 | NA | 5 |

| Navigation overall | 7 | 9 | 10 |

| Overall Experience | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| I connect by... | SMS | URL | URL |

| I went ‘tween objects by | D))) | arrows | arrows, D))) |

| I visited more objects | yes | yes | yes |

| use mobile browser | yes | yes | |

| Frequency mobile browser use | many x/day | many x/day | |

| use sms | no | no | |

| Find concept mobeum tour appealing? | yes | yes | yes |

Table 2 - Results from the second test of Open Museum’s mobile museum tour (Mobeum) at the Hood

When asked if they would choose to use their cell phone to take a museum tour, and Mobeum in particular, they all answered yes. Ease of use figured among the reasons they gave:

- Learn more on individual basis

- Interesting and informative content

- Great way to access museum information

- Control over content and pace

- Don't have to rent a headset

- Hygiene

- Like idea of being able to go to museums virtually

- Easily accessible

- Easy to use

- Normally don't take tours but would with my own cell

- Great feature: visitor choice of "More about this object"

- Ability to zoom in on photo detail

- Enriched my experience of a gallery that I've always disregarded

The final point (Mobeum enriched the experience of a gallery that I've always disregarded) prompted a long discussion about content creation. Participants concurred that they would be happy to go back to a museum over and over again, if the museum provided Mobeum tours with good, varied and fresh content.

The debriefing resulted in a list of ideas for content themes, including looking closely, art history, technique, composition, gossip, point/counterpoint, curators, and artists talking about their work. Participants also stated that additional content at the beginning and end of the tour would improve the experience and permit the museum to make a call to action: an orientation to a Mobeum Tour with instructions on how to find its mobile and desktop browser versions; an introduction to the collection from the museum director; and a closing page thanking the visitors and inviting them to become friends of the museum in order to stay in touch.

One test participant suggested that these tours might be an attractive lunch time option for colleagues in the Dartmouth College faculty and staff. Since it is common for them to go to the gym or some place else to get a break, why not package the Mobeum Tour as a 30-60 minute mind workout? If they liked it, they would be likely to return and recommend the Hood to others, including their students.

The upshot of this study is that the technical barriers to Mobeum appear to have been lowered to the point that content creation emerged as the critical issue for users. This is both the desired and the expected case. The primary design goal of a content delivery system should be transparency: to get the users engaged with the content, not with the delivery process or the technology.

We considered the test a success when one participant remarked afterwards, “My biggest complaint is that there wasn’t enough information. I would have liked to hear more.”

Getting Started

So far we’ve focused on how the visitor navigates between objects, but it is worth taking a moment to look at another important aspect of navigation: how visitors start the mobile tour. More precisely, how do they get their browser pointed at the starting page of the tour?

Initially, we had assumed that QR codes would be known entities and at least some of the participants would have QR code readers on their phones and have experience using them. We were surprised to find that not only did they have no experience with QR codes nor readers on their phones, but also no one knew what a QR code was. This situation is likely to evolve rapidly over given initiatives by Google Favorite Place (Google 2010) and Microsoft tag (Microsoft 2010) to promote (rival, naturally) 2D barcode technologies. In the meantime, however, the presence of the QR code on the Mobeum introductory panel at the Hood was a source of confusion.

Fig 9: Getting started panel from the second test of Open Museum’s mobile tour (Mobeum) at the Hood

We also found that some users were confused by our choice of a stylized D)) symbol for the Quick Code lookup button: it looked as if it might be the button for playing audio. In response, we changed the Quick Code lookup symbol to a bold hash # instead.

Across the two tests, SMS and URL tied for first place (over QR codes) as the preferred way to connect to the Hood tour, preference depending on how comfortable users were with texting versus browsing.

Fig 10: SMS server responds to the message ‘Hood’ during Mobeum test

The younger group preferred the SMS code. As daily text message senders, they found SMS comfortable, and their phones for the most part already had SMS accounts set up. According to the Nielsen report (Stewart, 2009), most mobile phone users in the world prefer texting, with younger people having an even greater preference for SMS. One tester (over 45) had never used the smartphone for texting and had signed up for a texting account. He remarked that the 20 cent fee per text could pose a barrier to use.

On the whole, however, the participants in the second test indicated that Mobeum was very easy to use for connecting to the collection, as well as for navigating between objects.

The Technology/Content Iceberg

Once the barriers to navigation were reduced, the next most important issue became content. Participants in both tests said that content had to be good and visitor-driven to hold their interest. For instance, they wanted to be presented with a range of options, be told how long each one would take (if audio or video), and be given an easy way to move on at will.

Fig 11: The Content Iceberg

In the second test, where we had clearly solved the major technical barriers to use, the major critique was that the Hood tour did not have enough varied content. At the same time, users found the content that was there to fascinating and were excited by the prospect that the museum would release the mobile tour and create more content over time. As stated above, many ideas about possible additional content emerged during the debriefing; such as ‘looking closely’, art history, technique, composition, gossip, point/counterpoint, curators, and artists talking about their work.

This introduces what we have come to view as the real challenge for implementing Mobeum (or any similar product) in virtuality and museum: content creation. Museums are notoriously slow to create content and cautious about accuracy, permissions, and distribution. The single most important factor determining the success of the digital outreach viral loop will be the ability of the museum to become a publisher of compelling Web content.

We would go so far as to say that the vitality of museums in the digital age depends on their ability to produce rich and engaging content concerning the objects in their collections. To do so, museums must stop thinking of themselves as disseminators of the single authoritative view on their collections and begin to see themselves as one Web publisher among many, competing for the attention, respect and support of their existing and potential audiences.

Next Steps

During the first phase of design and testing, which is the focus of this paper, we concentrated on creating an easy-to-use museum tour, as one part of an integrated bundle of content delivery services intended to set the stage for digital viral outreach. In the next phase of development, we will be turning our attention to making it easy for an unregistered Mobeum user to register and/or send tweets, posts, and comments from the gallery floor.

Currently, Mobeum users are invited to register for Open Museum when they complete a Tour. When they register, they are automatically signed up as friends of the museum (unless they opt out on the registration screen) and will receive occasional e-mail announcements of museum events (which they can easily turn off). Once registered users are signed in, they can bookmark objects and browse comment threads.

The next step will be to allow visitors (registered or otherwise) to use Mobeum to tweet or post Facebook status updates directly from the gallery; this feature is already possible from the mobile and standard browser versions of Open Museum. We are also exploring allowing users to register and sign in to Open Museum using their existing Facebook or Twitter account.

Our goals in this next phase will be to explore factors affecting :

- the quality and appeal of tour content

- the conversion of tour users to registered members and museum friends

- the sharing of objects with visitors’ social networks from the gallery floor

Conclusion

The use of mobile devices is on the rise, making it imperative to recognize that museum visitors will be carrying these devices into the museum and expecting to use them to enhance their visiting experience. Museums which are prepared for this eventuality, i.e. that have good Web content and appropriate delivery mechanisms in place for the three distinct usages (mobile tour, mobile browsing, desktop browsing), will be in an ideal position to capture visitors as friends and inspire them to champion the museum’s content via their social networks.

References

Godin, Seth (1999). Permission Marketing. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Google Favorite Places. “What’s that bar code?” http://www.google.com/help/maps/favoriteplaces/business/barcode.html Consulted January 31, 2010.

Krug, Steve (2006). Don’t Make Me Think! A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability, Second Edition. Berkeley: New Riders.

Microsoft Tag “What is Microsoft Tag?” http://www.microsoft.com/tag/ Consulted January 31, 2010.

Stewart, Jon and Chris Quick (2009). “Global Mobile -- Strategies for Growth” blog post at http://blog.nielsen.com/nielsenwire/online_mobile/global-mobile-strategies-for-growth/ Consulted January 31, 2010.