The Tech Virtual Museum Workshop

The Tech Virtual Museum Workshop is an on-line platform established to engage a global community of contributors to work collaboratively in a virtual, open source environment in the creation of interactive museum exhibits. It consists of two parts, a membership-based Web site and a multi-user 3D prototyping space. These two resources are used in tandem to intake and collaborate on design ideas.

The creation of an exhibit concept begins with a text description entered on the main Web site. Each exhibit concept is called a “project”. Files can be uploaded to each project's Web site to document the design. Multiple users have the ability to “join” any given project and form a team to work on the design elements. Similar features are provided within the 3D prototyping space, allowing users to edit group-owned 3D objects in real time, in a persistently accessible on-line space.

Rapid Prototyping

The use of The Tech Virtual platform, and the Second Life (http://www.secondlife.com) environment in particular, differs from traditional 3D modeling in three ways. First, whereas legacy 3D software runs on one's own personal computer for a single user, this software enables multiple users to view and edit 3D objects simultaneously. Secondly, skilled users of the software are able to prototype and build models at magnitudes of speed faster than is possible with traditional modeling software. The working environment is akin to sketching and rapid visualization before preparation for final design specifications. Thirdly, a built-in scripting language enables simulation of physical motion and interactivity that is not possible in other formats. Not only can these interactions be prototyped, but they can also be previewed by casual users for the purposes of testing and feedback. These low cost abilities provide enormous benefits to exhibit designers, educational content directors, and fabrication specialists.

Opening Museum Content to Collaboration

The platform allows multiple users to contribute to both the concept and content of exhibit projects. This concept encompasses input from museum and design professionals as well as from casual or hobbyist users. Each of these varied sources of input becomes relevant to stages of the design process. Ideas and project submissions by a wide variety of contributors are of high value as they give insight into the myriad perceptions that surround any given topic.

This process is also not exclusive to owners of powerful computers. While The Tech Virtual platform utilizes the software created by Linden Research Inc.as a collaboration tool and space, its use is not required to participate in the program. Users have completed entire exhibit projects using traditional modeling tools, uploaded sketches, videos, on-line interactives, and photos of physical models. Although this document emphasizes the core collaboration tools, they comprise only a part of the design activity in the program.

Fig 1: A Typical Gravity Well exhibit, photographed at Reuben H. Fleet

Science Center, October 2009, San Diego, USA

Example Exhibit Design Process

Here we will illustrate an example of how the platform can be used to redesign a commonplace exhibit such as a “Gravity Well”. The Gravity Well is installed in scores of museums and is a tried and true attractor with solid science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) learning outcomes (Exploratorium,1995). It is also an exhibit that is interesting when encountered in various scales and can accommodate multiple physical visitor inputs ranging from marbles to coins.

The Gravity Well's success as a stand-alone exhibit does not mean that it cannot be adjusted or modified for even more interesting encounters. In this example the designer wishes to modify the exhibit to become dynamic by using a flexible material such as a fabric as the rolling surface. She considers that this fabric could be pulled and stretched using attached handles. Using a combination of rapid prototyping and feedback from colleagues, she is able to try out several iterations of the exhibit.

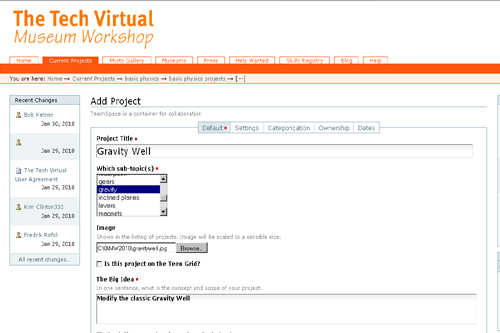

Fig 2: The Tech Virtual main page (http://thetechvirtual.org)

Creating an Account

Our designer starts at the main entry page (http://www.thetechvirtual.org), where she creates a user account. The user account will automatically track her projects, team memberships, comments and files uploaded. The sign-up process includes a user agreement (The Tech Museum, 2007) and an acknowledgment that all materials one uploads to the Web site may be freely licensed by a Creative Commons license (Creative Commons, 2010).

The designer then selects an appropriate category for the exhibit project. This project belongs to “Basic Physics” so the project is started under that category. If no appropriate category exists, The Tech Virtual can create a new category for any participating museum.

Fig 3: “Add project”on-line form example

(http://thetechvirtual.org/projects/basic-physics/basic-physics-projects)

Create a Text Description

The creation of the project page involves describing the proposed exhibit in a level of detail that makes it approachable and clear to other collaborators. The main exhibit description contains an overview of the interactive, and the Web site allows creation of additional wiki pages, uploading of files, to-do lists, and “help wanted” notifications. All of these features are used to network and collaborate with others. As an example reference of the level of detail that can be considered, The Tech Virtual provides a beginning checklist of exhibit components (The Tech Museum, 2009).

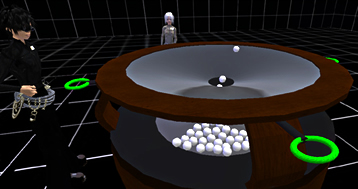

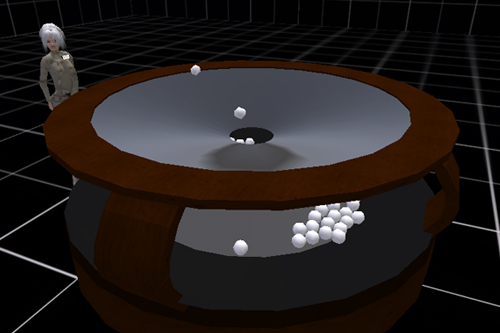

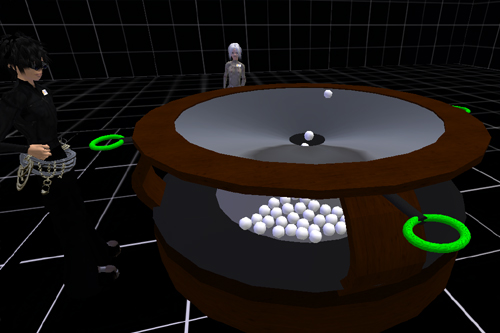

Fig 4: An editable open source Gravity Well model

Build a Model or Utilize an Existing Base Model

After creating a text description, the designer moves to the next phase which involves 3D prototyping. There happens to be an open source model of the Gravity Well already in the collection, so she locates it in her inventory of 3D items by simply searching for the name. Now, she is able to modify it. If no model exists for an exhibit concept, one can be built one from basic modeling units or a designer may utilize the on-line resources to locate someone who is willing to help fabricate a model.

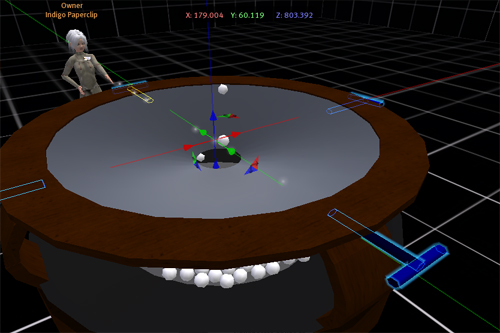

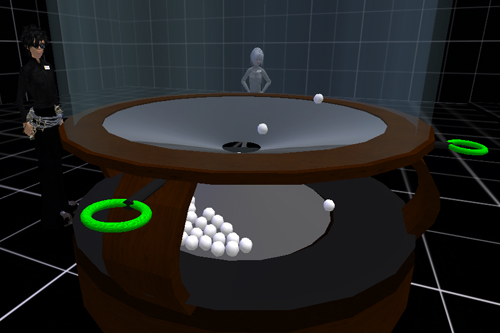

Fig 5: Blue handles as design elements applied to base exhibit model

Modify and Develop Exhibit Features

Our designer then begins to iterate and test various approaches, as if sketching. “What if the handles used to pull the fabric were 'T' shaped? What if they were circular? What if we make them blue or green? Does that make their purpose more or less clear?” Multiple choices can be made within moments. The marbles in the model can even be made to roll and fall with no additional programming required. The size, color, and position of objects can be adjusted at any time, making the development process extremely rapid.

Fig 6: Handles changed to circular shape and recolored to green

Test, Obtain Feedback, and Add Detail

Hyperlinks connect the Web page created for the project (In this example: http://thetechvirtual.org/projects/basic-physics/basic-physics-projects/gravity-well) and the 3D model (In this example: http://slurl.com/secondlife/The%20Tech%202/201/131/34) so that collaborators can locate both easily. During scheduled design review sessions, our designer solicits feedback from several other museum professionals and finds that the blue handles were not intuitive and could present usability issues to children with small hands or persons with limited gripping strength. Moreover, one user suggested that the flexible fabric might even cause the marbles to launch upwards if pulled too forcefully. Our designer considers placing a plexiglass enclosure around the exhibit to mitigate this issue.

Fig 7: Plexiglass shield concept added to evolving model

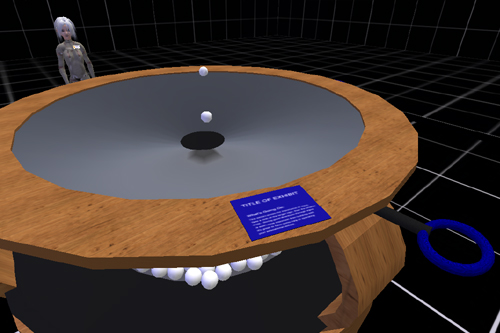

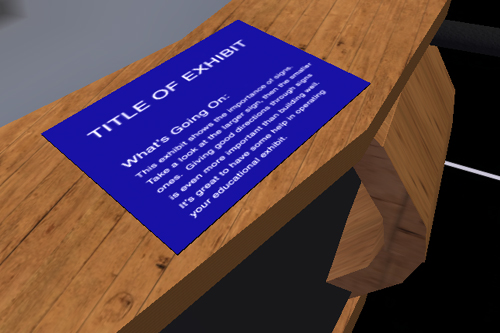

Fig 8: Applying signage and color schemes to the model

Forward Project for Fabrication

Our designer decides that the reconfigured Gravity Well is best without the plexiglass enclosure, and moves on to considering the signage placement. She also decides that the exhibit would benefit from a lightening of the wood tone to update its look and match a newer collection of exhibits. Color palettes and signage from working collateral can be uploaded directly into the on-line environment. After some additional testing of the signage placement and verbiage with external visitors, our designer calls on the fabrication team to realize the project.

Fig 9: Signage placement and verbiage can be tested simultaneously

with structural and interactive components

Many variations of exhibits can be considered and reviewed over a few weeks during a development cycle. Trained users have been able to prototype an entire gallery interior in this way in a shared environment without time-consuming e-mail exchanges of digital files. Traffic paths through a series of exhibits can also be tested, leading to advance troubleshooting opportunities before costly modifications are ever required.

Developing and Expanding Open Source Resources

Consider the opportunities for the future, when other designers from completely different museums may decide to try out previous versions of the handles, develop further ideas around the plexiglass enclosure, or visualize a complete rebuild. Using the Web site, they may choose to reach out to still other external individuals who could provide compelling and novel approaches to this staple exhibit. The contributing designers are then able to iterate using this expanding collection of open source design methods and materials, and to learn from the experiences of the previous versions. Each of these activities helps to build a dynamic knowledge repository (DKR) (Engelbart, Douglas, 1992) associated with the activity of hands-on informal science exhibit design.

References

Creative Commons, (2010). Attribution 3.0 Unported license legal code. Retrieved

January 20, 2010 from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/legalcode.

Engelbart, Douglas C., (1992). Toward High-Performance Organizations:

A Strategic Role for Groupware. Retrieved January 20, 2010 from

http://www.dougengelbart.org/pubs/augment-132811.html.

Exploratorium, (1995). Exhibit & Phenomena Cross-Reference: Gravity Well. Retrieved

January 20, 2010 from http://www.exploratorium.edu/xref/exhibits/gravity_well.html.

The Tech Museum, (2007). The Tech Virtual User Agreement. Retrieved January 20,

2010 from http://thetechvirtual.org/user-agreement.

The Tech Museum, (2009). List of Exhibit Components. Retrieved January 20, 2010

from http://thetechvirtual.org/projects/resources/list-of-exhibit-components.