Samuel Mann and Khyla Russell, Otago Polytechnic, New Zealand

Abstract

This paper provides an assessment of the success of SimPā from two perspectives: the milestones and objectives required of formal reporting and a more holistic Te katoa approach (everything). The SimPā project is a multiyear collaborative project that aimed to convey and strengthen Māori culture, tikaka and knowledge using digital technology. In short, the project aimed to provide a means of telling Māori stories in 3D game format. After five years, the project has achieved this through active engagement and participation, but the final outcomes are very different from those originally conceived. The representations of landscapes are examined in detail, from one perspective as providing the film sets for stories, and again as integral to the tribal context.

Keywords: Māori, narrative, culture, indigenous, game based learning, participatory.

Introduction

This paper is a review of the recently completed SimPā project.

SimPā, first described by Mann and Russell et al. (2006), was a collaborative partnership between the Otago Polytechnic and Kā Papatipu Rūnaka o te tai o Araiteuru. The project aimed to convey and strengthen research aspects in regard to Māori culture, tikaka and knowledge using innovative and cutting edge technology (notes on terms given at the end of the paper).

The contribution of this paper is to provide an overview of the project from two perspectives – that of the start and end of the project. The beginnings are summarised from project management documents and articles (Mann and Russell et al. 2006). Visual representations are used to provide structure for this analysis.

Perspectives from the Beginning

SimPā is a large scale initiative: Māori Game Design, or “Mātauraka ā whenua, ā moana, ā tākata ki te rorohiko”. The project aims to convey and strengthen Māori culture, tikaka and knowledge by initiating a process of participatory Māori digital media design using 3D game technology. It is intended that the project will assist in the creation of 3D game-based Māori digital content so that distinctly Māori voices, stories and cultural content can be encouraged and promoted.

This development will have benefits in terms of both technology and culture and the fusion of these two: Iwi digital content. The project will achieve this through active engagement and participation. It will:

- develop a process of participatory game development for Māori cultural content

- develop a SimPā toolkit to enable 1 (above)

- sevelop structures for use of resultant GamePā

- develop a new subject area and capability: that of training digital storytellers.

Note: SimPā is shorthand for the whole project; GamePā refers to the developed game for each individual rūnaka.

There are three major justifications for this project.

- The risk of Māori knowledge being lost due to the reduction of hapū knowledge repositories

- The well-publicised negative statistics of educational outcomes for Māori

- Consequent to (2), the lack of skilled practitioners of Māori digital content.

This dual need, of content and capability, is recognised by Iwi as both a limitation and an opportunity: “…communication technology is providing new avenues for our people to be enriched and contribute to our Kai Tahutanga regardless of time and location” (p17 Ngāi Tahu Vision for 2025, and Vision for 2025). The importance of Māori digital content is also key to the Government’s Digital Strategy:

Māori culture is a vital part of what distinguishes New Zealand from the rest of the world. ICT can be used to help create the conditions for the realisation of the diverse forms of Māori potential. It is crucial for the future of Māori and of New Zealand as a whole that distinctively Māori voices are encouraged and promoted. (p9)

It is important for New Zealanders from all walks of life to be able to create and use their own digital content in order to create value (social, cultural, and economic) for themselves, their communities, and our nation. (p12)

Māori are both creators and consumers of content and distinctively Māori content is particularly visible in the areas of: broadcasting; the arts and creative industries; as well as the education, health, and business sectors including tourism. Māori digital content is important not simply for its economic potential, but also as a vital means of expressing Māori culture in today's society and into the future, strengthening Māori society and identity, telling Māori stories to other Māori, and communicating with the wider world. Hence the importance of content being created and maintained in the Māori language. (p12)

2006 Model

This project brings together two components: the stories and the computing. By uniquely combining these aspects, a combination of benefits is made available that could not be accomplished by other means: it will

- Increase recognition, value and access to history and narratives of local rūnaka

- Give local rūnaka a unique narrative tool (one that appeals particularly to younger generations)

- Provide a virtual meeting place for whānau spread nationally and internationally in which they can interact in their own landscape

- Involve generations of Māori in gathering information and stories, encourage the preservation and creation of local Māori stories, increase the attractiveness of history to younger audiences and make Māori culture, mita (dialect) and tikaka accessible throughout the world.

Figure 1 provides an overview of the SimPā process. A key component of the project will be a series of marae-based wānaka. Each wānaka will be kaupapa Māori and participants will be immersed in tikaka Māori. Participants will learn about the traditions, environment, people and history of that place from local Rūnaka elders who are experts in Māori oral history and local knowledge. Using the “SimPā Toolkit”, participants will work alongside the Rūnaka members and supervisors to create a “GamePā” (a virtual environment representing a place). Based on the knowledge of Rūnaka members, participants will define the landscape, environment, and features of cultural significance, such as food gathering sites.

Fig 1: Wānaka process of participatory game design.

Objective 1: Develop and test a participatory approach to game development (Figure 1, top middle).

It brings together people from within the Papatipu Rūnaka who will jointly learn about their own place and stories, and convert this knowledge to digital form.

Objective 2: Develop a software tool for creating specific Māori virtual environments: the “SimPā toolkit” ~ he kohinga o ngā mea rauemi (Figure 1 top left).

Objective 3: Develop and test tools for the use of games in teaching Māori concepts.

This encompasses specific research on the effectiveness of digital game-based learning in a Māori context – use of the GamePā (Figure 1 middle).

Objective 4: Develop techniques and practices for the further use of GamePā (Figure 1, lower).

The resulting games will provide an interactive learning environment for use within each Papatipu Rūnaka. It is expected that this will enhance their mātauranga Māori, enabling individuals to connect and have respect for their landscape and historical stories. Each game will be the intellectual property of each Papatipu Rūnaka and provide an indigenous tool for future development in education and Māori business. We believe that this integrated model - using a resource that is interactive, on-line and multiplayer - will provide measurable benefits for individuals, whanau, hapū and Iwi.

Objective 5: Develop a new specialist area in education: Māori digital content.

We are developing a programme aimed at capacity building within indigenous people. By combining cultural knowledge with skills required for developing digital game-based learning resources, we hope to initiate a pathway to encourage careers in this area. This will provide career opportunities in education, information technology and business (Figure 1 right).

Objective 6: Develop a process of adoption of this initiative beyond the collaborating partners.

This collaboration is not just between a single group of stakeholders, but involves complex structures of knowledge ownership. An important part of this initiative is the development of processes maintaining the integrity of specialist knowledge and tikanga (Figure 1, lower).

Review

The SimPā project was funded in 2006 by the Digital Strategy through the Department of Internal Affairs. The project was completed in May 2009 although, as we shall see, lives on in many forms.

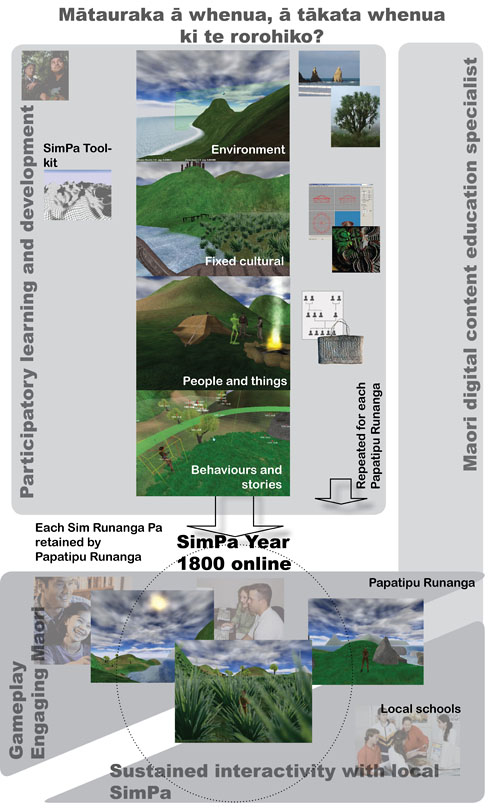

Figure 2 provides an overview of the process from a 2009 perspective.

Fig 2: SimPā at completion

Objective 1: Develop a participatory approach to game development (Figure 2 top).

The objective of bringing people from within the Papatipu Rūnaka who will jointly learn about their own place and stories, and convert this knowledge to digital form has been achieved. All Rūnaka engaged in the process of developing digital Māori content through a series of wānaka.

The linear flow of the SimPā development represented in Figure 1 has been very much more organic in practice.

The recreation of the landscapes (the first stage on the original process) had a fundamental impact on the Rūnaka. Without exception, the engagement at that stage was sufficient that further development (of the game environment) was unnecessary. No groups developed characters with scripted behaviour, in all; the landscape is the foundation of the story. The Rūnaka have had some extremely interesting debates about digital representation of images. For landscapes the debates are sometimes pragmatic – how to represent an area one group insists was always grassland whereas other families remember playing in the forest that once stood there. For people and stories, we need to recognise that there is rarely an objective truth. As the stories grow older, the representation of a single image in a digital setting becomes problematic – just what did this ancestor look like? In part this was avoided by not having direct characters, but also by recognising that this is “our” version of the story; it is quite acceptable for you to tell another version.

The software and equipment participants were educated in was Adobe Premier Pro, Adobe Photoshop, Torque engine gaming software, digital equipment handicams, still cameras and data management of such equipment. However, we found that for most people the prior skill level and time needed to master the Torque software was too great for the time we had to work with them. Also, participants wanted to see quick results, so we ended up having to hire a computer programmer to help Rūnaka complete the work that required use of the Torque software.

Objective 2: Develop a software tool for creating specific Māori virtual environments: the “SimPā toolkit” (Figure 2 left).

The “SimPā toolkit” was created. This includes a suite of software packages and game templates. At the end of the project, however, the “toolkit” is more about a process of engagement. The SimPā toolkit has been much more about process – partnerships of ideas and capabilities – than about the technology. The Rūnaka all decided to work individually and nominated representatives to lead their respective projects. This aligned with the aim that the Rūnaka members would define what information was important to them and how their resources would be produced. All Rūnaka representatives communicated with their members to keep them informed on the project and had the ambition of producing resources that would be beneficial for all members.

While the project was explicitly funded on the promise of game-based narratives, the team spent a very great deal of time engaged in wider knowledge – and wider applications of digital technology. For example, one Rūnaka has had a long-held special role as archivists for the Iwi. They saw the potential for SimPā to help with this role. Before the team could sensibly talk game environments, they spent time helping the Rūnaka with editing and sustaining existing media, and working with them to capture new stories in a variety of forms (image, video, oral history).

Integral to the process was developing an Intellectual Policy that ensured the Rūnaka owned the rights to all their knowledge and narratives, including the complete GamePā.

Objective 3. Develop and test GamePā in teaching Māori concepts (Figure 2 middle).

The uniqueness and process of the project saw the Rūnaka produce specifically tailored resources. In the original funding application, the GamePā were described using deliberately ambiguous terms. This was to allow all Rūnaka to tell their own stories. However, we did expect the project to focus on the original GamePā and that these would be “games”. We anticipated these GamePā to be developed as robust products (along the lines of a packaged game). We also thought further benefits would come from the use of the GamePā in marae-based teaching etc. None of the GamePā would be considered “games”, yet these benefits did occur, with most of the Rūnaka actively using their GamePā for “virtual tours”. What we did not expect was the form of the GamePā to vary so much. Resources were produced, such as complex narratives that use the game environment as “film sets” and virtual landscapes combining the game environment with other digital media – primarily audio and video. While the stories are hosted in the game environment, this was used as a platform for further engagement such as the recording and production of documentary style interviews that share stories of the past and present. None of the five Rūnaka GamePā could be considered “games” although all have made extensive use of the 3D gaming environment. These resources give access to the matauraka that they convey as well as the knowledge used to create them. They also provide a means of access for members, regardless of their location in the world.

Objective 4: Develop techniques and practices for the use of GamePā.

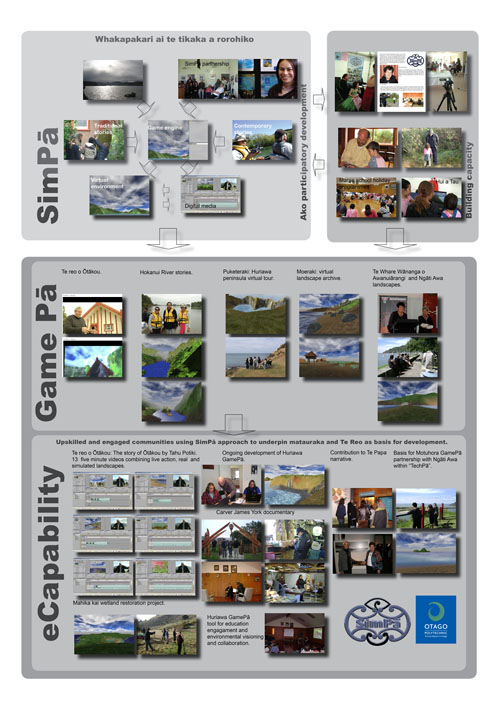

In addition to surprise at the form of the GamePā, we also did not expect the Rūnaka to move so quickly to using the skills learned through the SimPā developments to develop further applications (Figure 2 lower).

The measures of success can be viewed not only by the physical outcomes and ongoing use and production of further resources, but also by the actual process of engagement and dialogical exchange itself. The best thing to come from the SimPā project is the initiatives beyond the original GamePā. This demonstrates a very successful community adoption of digital media. These initiatives have included both game environment form and video form of GamePā, but put to quite unexpected uses.

The subject matter has extended beyond the traditional stories to include contemporary narratives: the story of Puketeraki’s new carvings, and Moeraki’s expedition to Te Papa (New Zealand’s national museum).

The relationship between SimPā and landscape was further explored by the Ōtākou rūnaka who used it in visioning wetland restoration to reform mahika kai.

One of the final phases of the project is the ‘handing over of both raw data and finished products’ before we evaluate and write conclusion papers. There has been surprise shown nationally and internationally (Russell and Mann 2007) that we were leaving the stories with the respective Papatipu Rūnaka. The assumption is that a project such as ours results in a contribution to a central archive. We have taken a very different approach: we have helped the Rūnaka retell their stories to themselves. In their new form they are still knowledge transmitted and retained within each Rūnaka.

Objective 5: Develop a new specialist area in education: Māori digital content

We had intended developing a specialist programme of learning aimed at capacity building within indigenous people. A Iwi Digital Practice Diploma programme was developed and approved, but did not run.

We believe, however, that a new subject area is emerging. This is apparent in the involvement of Rūnaka members in wānaka, and in the learnings of the SimPā team itself (Figure 2 right).

To ensure access to information specific to the creation and production of resources, a wānaka was held for all Rūnaka members. As expected (based on prior research), the attendees were teenagers, very enthusiastic about information technology. Parents and supporters viewed this wānaka as an opportunity for the rakatahi to learn and develop skills that can ensure the continuation and further development of such resources. Some of the Rūnaka are actively using SimPā to connect with their youth. Other training and wānaka that were held also provided opportunities for participants to develop their capability.

The partnership has evolved significantly. The most important change was a realisation that to achieve the outcomes the SimPā team had to be indistinguishably both Otago Polytechnic and Iwi. The most successful capacity building has been of this evolving team. We see this as a very positive outcome. The project has taken far more partnership negotiation than we ever imagined. This has been constant and evolving. We believe that this model of engagement could be the model for further partnership.

Objective 6: Develop a process of adoption of this initiative beyond the collaborating partners.

This collaboration is not just between a single group of stakeholders, but involves complex structures of knowledge ownership. An important part of this initiative is the development of processes maintaining the integrity of specialist knowledge and tikanga (Figure 2 lower right).

Otago Polytechnic has also developed a proposal to use GamePā to connect Māori living overseas back to their Rūnaka: they are currently seeking funding to develop it further. This project will use virtual realities of people and places of tūpuna acting and interacting in these virtually created spaces. Kai Tahu people far from home can access these histories and te reo of their places; of ancestors and their deeds; of how to give this new knowledge to their children, many of whom have never set foot on these landscapes.

Rūnaka are currently in discussion with the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries and local Rūnaka about using the GamePā format to create an interpretative resource for Mahika Kai.

Further collaboration between Otago Polytechnic and the eWānanga Centre for Creative Teaching and Learning Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi is also in the pipeline.

Conclusions

“SimPā” aims to integrate participatory digital interactive storytelling with Māori culture, tikaka and knowledge. The SimPā project uses gaming software to create various ‘GamePā’, which are virtual environments based on actual places. These environments incorporate the knowledge of Rūnaka members, recreating sites of cultural significance and historical environmental features that have since changed with the passing of time. The outcomes of this project were the completion of GamePā and narrative films incorporating digital content with Te Rūnaka o Ōtākou, Kati Huirapa ki Puketeraki, Te Runanga o Moeraki, Hokonui Rūnaka and Ngāti Awa. Topics included migration stories, the virtual recreation of a wetlands restoration project, and local oral histories.

Our indigenous literature in times past was, and in many ways, continues to be, expressed through whakairo, (carving) and painted kowhaiwhai (specific Iwi patterns based on nature often presented in the abstract); through tā moko (commonly called tattoo) and by way of tātai kōrero (stories of connectedness)and lastly, by use of and engaging in kōrero neherā (ancient histories and prehistorical narratives). These stories if not these landscapes have been retained through endless generations of bodies of knowledge being lovingly held as precious by the keepers who have been charged with their kaitiaki . Thus they ensure as they commit to memory his and her stories of our land and seascapes, of our and Tūpuna a - whānau who formerly occupied the aforementioned that we in this time and place, continue to occupy, if not always own. Using contemporary technologies, we can retain these stories and design new means of imparting them to our Iwi wherever in the world they may be located. It is also about safeguarding and protecting our knowledge and knowledge systems whilst using new means of disseminating these. The stories that have been re-created are placed squarely within Iwi epistemologies, ontological understandings and mātauraka. The paper provides a model of connected cultures at times intruding into each other, but finally providing a collaboration and complementarity that enhances both.

Looking back, SimPā is quite different to how the team first conceived it. Despite these differences, or perhaps because of them, the project has met expectations. One of the main lessons learned from this project is the need to abandon a linear flow to accommodate a process that is very much more organic.

At the start of the project the team proposed a process of participatory development for each Rūnaka. For each group they saw a process of helping the community identify important stories and then convert these stories to a game-based environment. Of primary importance to the original project was the “SimPā toolkit”. However the SimPā toolkit has ended up being much more about process – partnerships of ideas and capabilities – than about the technology. In addition, the development of each GamePā has been quite different to what we expected. None of the five Rūnaka GamePā could be considered “games”. All, though, have made extensive use of the 3D gaming environment.

It was hoped that the resultant GamePā would be used in engaging and educating the community. The original goal for “Sustained interactivity” was the use of these GamePā with Rūnaka’s work with schools, and possibly in tourism ventures, etc. The intended target for the project, “teenagers dis-engaged from both their culture and education”, proved hard to hit. However, the team had most success with people with young families (widely recognised as crucial for cultural development), the very young, and the more mature. Some of the Rūnaka, though, are actively using SimPā to connect with their youth. However, the use of SimPā as a recruitment tool for students into computing did not occur. While the team believe there is still a role for the “Māori digital education specialist”, it is difficult to see a predictable career path into this.

The project has taken far more partnership negotiation than the team ever imagined. This has been constant and evolving and is a model of engagement for further partnerships. The most important change was a realisation that to achieve the outcomes, the SimPā team had to be indistinguishably both Otago Polytechnic and Iwi. The most successful capacity building has been of this evolving team. The team sees this as a very positive outcome.

Because of the partnership approach, SimPā has evolved dramatically since its conception. Rūnaka determined that the landscapes should become a major focus: the participants were so excited by the process of re-imagining and re-building the landscapes that the notion of the game format became less important. What is happening now is that they are using these elaborate 3D environments as film sets, as a way to tell narrative stories. Each group has decided on a different approach using their GamePā to record a range of traditional knowledge; e.g. telling migration histories; recording their oral histories; describing cultural, traditional and botanical education; describing kai Māori (traditional foods, especially seasonal delicacies)and karakia (Incantations)and tikaka and for memorial purposes. This has required the project team to be adaptable and resourceful to adapt the original idea to fit the needs of the communities. This has been essential for the project’s success. The team members have also needed to adapt their approach to work not just with Rūnaka but also with different whanau groups within the Rūnaka.

The future usefulness and sustainability of the SimPā process is assured through the new projects both the Polytechnic and Rūnaka are currently pursuing.

It is evident that there is a need to develop and offer different models of teaching and learning: models that vary in content, specifically iwi digital content, and structure with a flexible structure and delivery that will benefit community users; eg, wānaka, marae based teaching, flexible hours, units etc.

Notes on Maori terms

Tā moko (often referred to as tattoos) in the cultural context are as unique to the person as is their thumb print and usually decided on by either the tā moko artist or whānau (family) member/s. Tattoos, on the other hand, are often given to many people based on choice or a liking for the pattern Stories of connections and connected up stories

kaitiaki: Holders or keeper guardians of the many bodies of knowledge.

tūpuna rokonui: Ancestors accredited with famous (or infamous) deed or feats of achievement.

Matauraka Iwi: Knowledge systems and ways of learning

Wānaka: Total immersion workshops over a number of days

Tikaka: Correct behaviours

Iwi, Kai Tahu: Tribal name of the south island Iwi

Tupuna whānau: Ancestral families

Rūnaka: Localised subclan council

Papatipu Rūnaka: Regional Iwi council of unbroken occupations and villages

tātai korero: Connectedness through narrative of ancient people/places

kōrero neherā: Old stories of two-way migrations and wider Pacific peoples’ relationships as Polynesian clans to older times.

Acknowledgements

This collaborative project is developed as a result of the Memorandum of Understanding between Otago Polytechnic and these Rūnaka. This MOU is instantiated in the position of the Kaitohutohu and the KōmitiKāwanataka. The SimPā team has immensely enjoyed working with the following individual Rūnaka, and the committee of the combined Rūnaka of Arai te Uru.

- Te Rūnanga o Ōtākou

- Kāti Huirapaki Puketeraki Runaka

- Te Runanga o Moeraki

- Hokonui Rūnaka Incorporated Society

We would also especially like to acknowledge Kelly Davis from one of the key partners Te Matauranga Putaiao Trust who died suddenly as the project got underway. Kelly was a key figure in the project and is sadly missed.

Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu head office has also been very helpful in the SimPā project. We are grateful for the assistance of (then CEO) Tahu Potiki and especially the GIS expertise of Jeremy King.

We have also enjoyed working with Ngāti Awa, facilitated through Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi.

The SimPā team has evolved over time. The authors are grateful for the support of Victoria Weatherall, Paul Admiraal, Jenny Aimers, Leigh Blackall, Amber Bridgeman, Justine Camp, Sunshine Connelly, Mark Crook, Rachel Dibble, Dougie Ditford, Evelyn Davis, Gwyn John, Marlene McDonald, Karen Love, Alistair Regan, Thomi Richards Lesley Smith, Dana Te Kanawa, Andy Williamson, Jeanette Wikiaira, Vicky Wilson and members of the Kōmiti Kāwanataka.

References

Mann, S., K. Russell, et al. (2006). “Māori Game Design”. 19th Annual Conference of the National Advisory Committee on Computing Qualifications, Wellington, New Zealand. NACCQ in cooperation with ACM SIGCSE. 165-174.

Ministry of Economic Development (2005). The Digital Strategy: Creating Our Digital Future. Retrieved March 1, 2006 from http://www.digitalstrategy.govt.nz

Ngāi_Tahu (2003). Ngāi Tahu 2025. Christchurch.

Russell, K. (2008). “Two Cultures: Balances, Choices and Effects Between Traditional and Mainstream Education”. Oxford Round Table, Oxford, England. Copy of the full paper online here http://computingforsustainability.wordpress.com/2008/08/18/SimPā-as-a-model-of-partnership/

Russell, K. & S. Mann (2007). “Worlds Colliding: participatory storytelling and indigenous culture in building interactive games”. ICHM Conference, Toronto, Canada. 24 - 26 October. http://www.archimuse.com/ichim07/papers/mann/mann.html

An earlier version of this paper was presented as a supplementary paper at the National Advisory Committee on Computing Qualifications in Napier NZ 2009.