Introduction

Eye and gaze-tracking has been subject of research interests for over a century (Huey, 1908). Even though early applications focused on interpretation of the gaze pattern in interpretation of works of art (Yarbus, 1967), the technology was adopted mainly by researchers in the fields of psycholinguistics (for example, see Rayner & Pollatsek, 1987); design of modern car controls (Yu-ming and Li, 2007); as a focusing device in traditional film cameras; and for the most part, in Web design and marketing research (Google, 2009), as well as for the design of mobile devices (Pölönen et al, 2003). An attempt made by the National Gallery of Art in London to collect gaze patterns of visitors using eye-tracking equipment also yielded some publishable data (Wooding, 2002).

The technology started by using very primitive techniques (for example, affixing small mirrors with suction cups to the eyeballs of ‘subjects’); it has benefited greatly by the advancement of digital technologies. Modern eye-trackers can be easily attached to a laptop (or be built into one), and sophisticated software analysis allows free head movements while still tracking the gaze direction of the viewer.

Eye- and Gaze-Tracking Overview

Although it is possible to use a wide variety of methods to track the eye movements (see Duchowski, 2002), currently the most widespread and commercially available method is to use infra-red illumination of the eye and infer gaze direction by comparing the position of the pupil relative to the position of corneal ‘glint’ (that is, a spot of reflected light from the cornea that exists whenever there is enough ambient light to see; see Figure 1). A non-technical description of the methodology that is relevant to museum professionals can be found in an earlier paper (Milekic, 2003).

Fig 1: A photograph of an eye showing the position of the pupil (A & B) and the “glint”

Although the existing technologies have found their commercial applications in a variety of fields like Web design, product design and various areas of research in the cognitive science area, several obstacles prevented their broader use. These problems are related to:

- cost of eye-tracking equipment

- portability

- ease of use

- eye-control interface design.

The first three problems are mainly related to technologies currently used in eye-tracking and will be dealt with in the following section. Eye-control interface problems belong to an entirely different category and will be addressed separately.

Low Cost Eye-Tracking

One of the major barriers for the development of eye-tracking applications is the cost of the equipment itself. Current prices range from $6000 to $40.000+ and are often just for the lease of equipment. When these technologies were originally developed, existing personal computers lacked sufficient processing power and special video input. However, during the last decade personal computers have dramatically improved processing speed, amount of storage and communication with external devices (USB2 ports, fire wire port). At the same time, consumer driven demand for free video communication over the Internet has led to miniaturization and increased resolution of Web cams. Indeed, nowadays an average laptop (as well as mobile devices like cell phones) comes equipped with built-in cameras whose technical specifications exceed the ones of commercially available products from just a few years ago. Since the minimal technological requirements for eye-tracking became available either as cheap off-the-shelf devices (Web cams), or were integrated into existing devices, it is not surprising that a number of researchers and innovators turned their attention to this area.

Web cam based eye-tracking

It was in 2002 that one of the first papers on the possible use of Web cams in the area of eye-gaze assistive technology was published (Corno, Farinetti, Signorile, 2002). However, while it provided handicapped users with an alternative way of interacting with digital content, the software was slow and imprecise (see the more recent paper by Corno & Garbo, 2005 for a more sophisticated solution). It is only in the past two years that the use ofWweb cams as eye-tracking devices has received new interest. The following sections provide an overview (by no means exhaustive) of both professional researchers and computer enthusiasts who have designed low-cost or free (open source) software for Web cam based eye-tracking.

An example of academic research for low-cost eye-tracking is provided by Piotr Zieliński’s Opengazer as open-source software using an ordinary Web cam (see references for Web link). The most recent version of the software also provides face-tracking and the recognition of facial gestures (for example, smile and frown detection).

A group of researchers from the IT University of Copenhagen (San Agustin et al, 2009) has developed an open-source eye-tracking program ITU Gazetracker, as well as applications that use eye-tracking for text input (GazeTalk, StarGazer) and an application which allows eye-controlled interaction with video content on the popular YouTube site (EyeTube).

Fig 2: Setup screen from GazeTracker

Another single-camera eye-tracking system has been described in detail by Hennessey at al. (2006). Besides academic research, eye- and gaze-tracking has attracted the attention of numerous open-source programmers, hackers and artists as an alternative way of interacting with digital content. Perhaps the best example of such efforts is the EyeWriter project (http://www.eyewriter.org/) where a group of programmers, artists and designers (Members of Free Art and Technology (FAT), OpenFrameworks, the Graffiti Research Lab, and The Ebeling Group) came together to design a cheap eye-tracking device to help their friend Tony Quan, an LA graffiti writer, publisher and activist who was rendered paralyzed with the onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Fig 3: Tony Quan with eye-tracker built with off-the-shelf components (image from: http://www.eyewriter.org)

A similar system (head mounted) was described under the name openEyes and can be built using open-source software and cheap hardware (Li, Babcock, Parkhurst, 2006).

Applications using eye-tracking

Often, many of the applications using eye- and head-tracking were developed by independent programmers for first person ‘shoot them up’ games. In these games the player’s eye controls the cross-hairs on the screen, making the experience of shooting the opponents equivalent to looking at them (on the screen) and pressing the trigger button. Examples include the head-tracking program CameraMouse (see Web references) and the game Aliens. Eye-tracking has been successfully integrated with a number of popular games, like Quake II, or Warcraft. Using the keywords “eye-tracking” and “games” will bring links to a dozen examples on YouTube.

Museums and eye-tracking

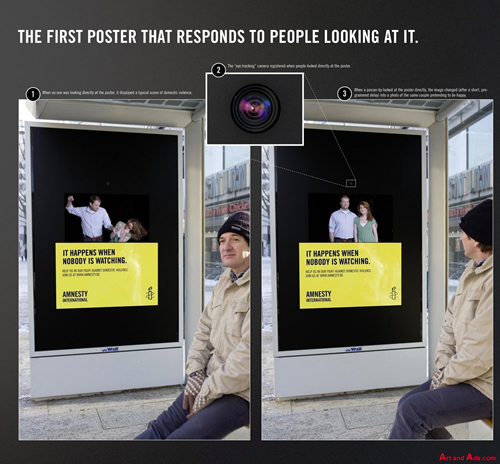

The use of eye-tracking in museums has been severely limited, mainly due to the problems associated with a museum professionals’ general lack of knowledge of the existing technologies as well as the difficulties of setting up the equipment for a large number of diverse visitors. However, recent advancements in marketing with eye-aware displays, as well as a number of interactive art installations that use eye- and gaze-tracking,have sufficiently demonstrated that the technologies in question are mature enough for use in public spaces. For example, Amnesty International has sponsored the development of a poster that raises awareness about domestic violence. The poster entitled “It happens when nobody is watching” depicts a seemingly content couple; that is, only when one is looking directly at it. However, when one turns the gaze away, the scene changes dramatically to that of a violent beating (Figure 4).

Fig 4: Amnesty International poster using eye-tracking

The video installation “Big Smile” by a multimedia artist Brian Knep uses the same technology – a large “smiley face” has a growing smile as long as no one is looking at it. The moment it detects a pair of eyes looking at it, it puts on a “straight face” with no smile (Knep, 2003).

One of the first large scale studies involving the use of eye-tracking equipment in a museum was undertaken by the National Gallery in London, during the exhibit “Telling Time” (Figure 5). However, besides demonstrating that it is possible to use eye-tracking technology in large scale exhibits, the study did not substantially enhance museum’s visitor experience.

Fig 5: Early data from the experiment showing fixations and scan-paths of participants looking at Paul Delaroche's 'The Execution of Lady Jane Grey' (National Gallery, London & Applied Vision Research Unit at the Institute for Behavioral Sciences, Darby, Exhibition “Telling Time”)

The author of this paper is of the opinion that eye- and gaze-tracking technologies have huge potential for use in the areas of physical museum visitors’ experience, as well as for the enhancement of museum presence on the Web.

Proposed Research & Applications

It is important to note that the following proposals are based on currently available technologies and methodologies that were already successfully used in other areas such as marketing or product design. Possible museum applications can be broadly grouped in two categories:

- gaze-aware applications, and

- gaze-controlled applications.

Gaze-aware applications are those where a user’s gaze direction and fixation location are tracked, and based on this information, the application can trigger an event. The observed articles can be physical paintings, large scale projections, screens and even sculptures. The triggered events would most likely have the function to provide additional information that is relevant to an observer’s interest, as specified by gaze direction.

Gaze-controlled applications are the ones where a user can actively interact with content (displayed on a screen, or projected) by using eye-movements. This approach has large potential for use in Web-based museum applications since the content is already digitized and presented on a screen.

Of course, it is entirely possible to create applications that would use a mix of both approaches.

Gaze-aware applications in museums

Figure 6 illustrates a possible gaze-aware application in a physical museum. What is depicted is an explanation of the process. A museum’s visitor experience would be that of looking at the physical painting. However, focusing attention on a certain detail (for example, the face) would “magically” start an appropriate narrative (depicted by callout boxes next to gaze fixation points).

Fig 6: An example of gaze-aware information delivery in a museum setting. Red circles indicate points of gaze fixation. Callout boxes indicate the triggering of a target specific voice narration (painting from the Clay Center, Charleston, WV in an interactive application designed by the author)

Figure 7 illustrates similar approach for the viewing of a large scale artifact, in this case a mural depicting a sequence of different scenes. Looking at the mural through the oval “viewing window” (which ensures that the viewer’s eyes will be at the specific location and thus trackable) positions a spotlight corresponding to one’s gaze direction and triggers a voiceover that is relevant to gaze fixation.

Fig 7: A possible setup for gaze-guided audio delivery. The marked parts of the installation are as follows: (A)observed artifact (B)eye-tracking mechanism (infra-red light emitters & camera) (C)viewing station with built-in speakers (D)gaze ‘focus’ spotlight(E)computer projector

Gaze-controlled applications for museum content

While gaze-controlled museum applications can be displayed in physical museums, their true potential is unleashed in combination with inexpensive Web cam-based eye-tracking. Web cams are already a standard feature of modern laptops, and based on the number of previously described open-source programs, it is only a question of time until Web-based content (or, for that matter, anything displayed on a screen) will be open to yet another source of input – a user’s gaze. Interest in these methodologies is not trivial and may have huge commercial implications - as indicated by the fact that one of the leaders in the design of digital devices, Apple™, has recently acquired the largest eye-tracking equipment manufacturer (Tobii™). Academic research is following the same trends. Recently, as a part of cross-discipline collaboration named StudioNext, two teams of students from different departments at the University of the Arts were investigating possible eye-tracking applications (StudioNext, 2009).

Any gaze-controlled application has to solve a problem which is known in literature as “Midas touch” – that is, it has to be able to differentiate between looking at something just for sake of observation and looking at something in order to initiate some action. The most common solutions to this problem are either time-based (for example, fixating a button on the screen for a period of time will eventually lead to a simulated mouse click), or location-based (looking at certain parts of the screen defines the function of gaze control, similar to a ‘tools palette’ in many programs).

In a previous paper (Milekic, 2003), I described yet another method of solving this problem – by using “eye gestures”. In short, eye-gestures are voluntary rapid eye movements, for example to the left, right, up or down, which are not usual during normal observation. One can think of them as “eye-signals” that we sometimes make, for example, to silently indicate a person we are currently talking about. Depending on the context these eye-gestures can be assigned different functions and can provide sophisticated hands-free interaction with digital content. For an example of possible actions triggered by eye-gestures, see Figure 8.

Fig 8: Arrows indicate the direction and range of eye-movements and functions assigned to them. Moving the eyes in a normal fashion does not trigger any actions.

The following illustrations provide an example of hands free interaction with museum content, either in a physical museum (using a projection screen) or on a computer screen with Web content. The proposed interface allows selecting an object (on the vertical right hand panel) just by looking at it. The selected object is displayed in the viewing panel on the left. Using eye-gestures it is possible to zoom-in (glance to the left), zoom-out (glance to the right), grab (glance up) and drop the object (glance down). While the object is “grabbed” it will follow the gaze direction, allowing examination of different areas under magnification, until it is “dropped” (Figure 9).

While “hands-free” manipulation of objects on the screen may seem trivial in a museum Web site context (although it is not in the case of a neurosurgeon interacting with CAT scans of a patient’s brain during an operation), it can be combined with gaze-awareness of objects which can deliver additional information about specific detail that the viewer is looking at.

Fig 9: Example of a gaze-controlled museum Web collection interface. Eye-movement to the left zooms into the image. Looking up would “grab” the image and allow inspection of different parts. A scrollable panel on the right allows choosing another image.

Another way of using gaze-tracking for Web-delivered content would be to “attach” different tools to a viewer’s gaze. Figure 10 illustrates the use of a magnifier tool – the magnifier follows the user’s gaze. Of course, it is possible to imagine a wide variety of “gaze tools”; for example, X-ray vision of the painting, microscopic examination of the painting.

Fig 10: An example of gaze-controlled magnification. The magnifier is “tied” to a viewer’s gaze.

Eye-tracking and knowledge dissemination

Eye-tracking does not have to be constrained just to interactions with objects displayed on the screen. Some of the recent studies indicate that eye-tracking can dramatically influence the efficacy of knowledge transfer and retention. A study by Ozpolat (2009) provided a model that will deliver information (based on eye-tracking data) in a way that corresponds to a viewer’s learning style. With the changing role of museums since the introduction of the digital medium, shifting from conservation and preservation to education and knowledge dissemination, this may play a crucial role in how museum information is delivered, both in the physical museum and on the Web.

Eye-tracking and museum studies

Eye-tracking may prove to be the most powerful tool for museum studies. If Web cam-based eye-tracking becomes a reality, one can only imagine what kind of data will become available to museums. So far, only large corporations are benefiting from controlled eye-tracking studies, mainly for marketing purposes. In academic circles, the last decade was marked by increased interest of cognitive scientists in what came to be known as “neuroaesthetics” (Skov, 2009) – a study of neural bases of our perception of beauty. The sad truth is that so far, the success or failure of major exhibits could only be judged by marketing criteria (how many visitors) and not by the impact the exhibit actually had on visitors. Web cam-based data collection would be free and automatic and provide us with a “missing link” of data – what is it that museums Web site visitors are actually looking at?

Conclusion

For the sake of clarity, I would like to summarize the points that were addressed in previous sections. They are:

- cheap Webcam-based eye-tracking already exists

- it very likely will be incorporated into a new generation of digital devices (laptops, netbooks, iPads, etc.)

- eye-tracking on its own, and specifically Web cam-based eye-tracking, offers new ways of interacting with museum content, both in a physical museum and in Web-delivered content

- eye- and gaze-tracking data may play a crucial role in museum Web site design and content delivery, as well as exhibition planning in physical museums.

As with other major revolutions that happened with the introduction of digital media, like the possibility of having a museum Web site, digitizing museum collections, and more recently, delivering content via mobile devices (like iPods and cellular phones), the only question is:

Are museum professionals going to wait for someone else to define their future, or are they going to take an active role in it?

References

Corno, F., L. Farinetti & I. Signorile (2002). A Cost-Effective Solution for Eye-Gaze Assistive Technology. ICME 2002: IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo, Lausanne, Switzerland

Corno, F., and A. Garbo (2005). Multiple Low-cost Cameras for Effective Head and Gaze Tracking. 11th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Las Vegas, USA, July 2005. Available at: http://www.cad.polito.it/FullDB/exact/hci05.html

Duchowski, A.T. (2002). Eye Tracking Methodology: Theory and Practice. Springer Verlag

Hennessey, C., B. Noureddin, & P. Lawerence (2006). A Single Camera Eye-Gaze Tracking System with Free Head Motion. ETRA 2006. San Diego, California, 27–29 March 2006

Huey, E. (1968) The Psychology and Pedagogy of Reading (Reprint). MIT Press 1968 (originally published 1908), available as full text at: http://books.google.com/

Li, D., J. Babcock, D. Parkhurst (2006). “openEyes: A low-cost head-mounted eye-tracking solution”. In Proceedings of the ACM Eye Tracking Research and Applications Symposium.

Knep, B. (2003). Big Smile. Available at: http://www.blep.com/bigSmile/index.htm

Milekic, S. (2003). “The More You Look the More You Get: Intention-based Interface using Gaze-tracking”. In D. Bearman & J. Trant (Eds). Museums and the Web: Selected papers from Museums and the Web 03. Pittsburgh: Archives & Museum Informatics, consulted on 1/31/10 http://www.archimuse.com/mw2003/papers/milekic/milekic.html

National Gallery in London (2000). 'Telling Time' exhibit eye-tracking report, consulted on 1/29/2010 http://www.lboro.ac.uk/research/applied-vision/projects/national_gallery/index.htm

Ozpolat, E., G. Akar (2009). “Automatic detection of learning styles for an e-learning system”. Computers & Education 53, pp. 355-367.

Pölönen, M., H. Juha-Pekka, P. Kimmo & H. Jukka (2003). “Handheld device usability studies with eye tracking”. ECEM 12, August 20 - 24, 2003, Dundee, Scotland 2003.

Rayner, K., & A. Pollatsek (1987). “Eye movements in reading: A tutorial review”. In M. Coltheart (Ed.), Attention and performance XII(pp. 327-362) Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

San Agustin, J., H. Skovsgaard, J.P. Hansen and D.W. Hansen (2009). “Low-cost gaze interaction: ready to deliver the promises”. In Proceedings of the 27th international Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Boston, MA, USA, April 04 - 09, 2009 CHI EA '09. ACM, New York, NY, 4453-4458. Available at: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/1520340.1520682

Skov, M., & O.Vartanian (eds.) (2009). Neuroaesthetics (Foundations and Frontiers in Aesthetics), Baywood Publishing Company, Amityville, New York.

Wooding, D.S. (2002). Fixation Maps: Quantifying Eye-movement Traces, ETRA'02 New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, available at: http://www.cnbc.cmu.edu/~tai/readings/active_vision/wooding_fixation_map.pdf

Xu S., H. Jiang, & F.C.M. Lau (2009). User-Oriented Document Summarization through Vision-Based Eye-Tracking. IUI’09, February 8 - 11, 2009, Sanibel Island, Florida, USA

Yarbus, A. L. (1967). “Eye Movements and Vision”. Plenum. New York. 1967 (Originally published in Russian 1962).

Yu-ming, C., & L.W.Li (2007). The Visual Power of the Dashboard of a Passenger Car by Applying Eye-Tracking Theory. SAE World Congress & Exhibition, April 2007, Detroit, MI, USA.

Zielinski, P. Opengazer: open-source gaze tracker for ordinary webcams. Consulted on 1/30/2010 at http://www.inference.phy.cam.ac.uk/opengazer/

Web links

Amnesty International eye-tracking poster: http://www.artandads.com/tag/eye-tracking/

CameraMouse: http://www.cameramouse.org/index.html

EyeWriter Initiative: http://www.eyewriter.org/

Google eye-tracking study: http://googleblog.blogspot.com/2009/02/eye-tracking-studies-more-than-meets.html

StudioNext project at the University of the Arts, Philadelphia: http://www.uarts-eyetracking.org/