Introduction

The challenges of maintaining a dynamic and relevant museum Web site are significant. Many museums have on-line collections numbering tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of objects. Presenting these collections requires the integration of imagery, meta-data and bodies of text which describe not only the object itself, but also the historic and cultural contexts which make them important. In addition, museums are continually creating a large variety of associated content and media. Increasingly, this associated content is being created by staff with little formal training or exposure to Web technologies. Given the mandate to create this type of on-line content and the desire to continue to document a wide range of activities in education, conservation and publications, museums will quickly encounter a series of technical bottlenecks which make that job very difficult.

While the scope of this problem is accelerating, the problem itself is not new. Museums have long sought to make this type of content available on-line, and many have succeeded in creating very engaging on-line experiences which feature content from all these areas. The problem of sustaining and maintaining this development over a long period of time is multiplied when we consider the rate of change of the Web today. Change is the one constant we can count of when it comes to predicting the evolution of technology and Web practice. Technologies and trends which were common just 3 years ago now appear dated and unfamiliar. The content is still fresh, but its presentation belies the inflexibility of the underlying system. More and more, museum Web sites are beginning to adapt to this pace of change by undergoing an iterative and continual re-design process instead of opting for huge overhauls every 3-5 years. As we accumulate increasing amounts of content whose origin was on the Web, how can we succeed in migrating and re-presenting that content in a way that can adapt to these changes?

While the task of maintaining this content is formidable, so is the task of creating rich content in the first place. While Web authoring tools have become considerably easier to use recently, the process of creating a media-rich and well formatted Web page is still not a trivial issue. In most museums, this task falls to a Web editor who is skilled in HTML markup and understands enough of the CSS templates within the site to maintain a consistent look and feel for each page. This reality creates a barrier between the content experts in various departments and the publication of their content on-line. This makes it very difficult to generate large amounts of new content on a continuing basis.

A Simple Scenario

While it may seem that museum data should contain mainly static information, the museum-Web professional will quickly relate to you many stories about how this is not the case. Museum datasets are constantly being refined, extended and researched in ways that result in new or changing information. New photography continues to improve the ways we can represent our collections on-line. As user-generated content becomes more integrated in the way we view our collection data, the impact of dynamic data will multiply. How then should we represent the collection in the context of other interpretive information?

To take a simple example, let's suppose our curator of American Art has written an article about Edward Hopper for an upcoming exhibition and would like to feature several works of art alongside that text on the museum's Web site. Typically the museum's Web team would receive the content from the curator in order to format the text in HTML and CSS to be suitable for presentation on-line. In the best case, we already have up-to-date photography and meta-data for the works in question. Web editors then retrieve and format an appropriate image and caption for the Web article, perhaps using an appropriate CSS ID to insert the images as a pull quote in the article. The resulting text and images can then be added to the Web site content management system (CMS) for publication.

This solution works well until the curator requests new photography prior to the exhibition, or until corrections to the meta-data are made by the registration department. Either of these changes requires accurate communication between the departments and the correction of the appropriate text or media by the Web staff. What may seem feasible in this simple example becomes impossible when we consider a more realistic scale – perhaps thousands of similar articles. The problems continue, if the Web developer wants to enhance the way the collection or images are displayed on the Web site. In this case, each enhancement will require changing the content for each article individually. How can museums be more effective in managing and displaying these datasets and content? The remainder of this paper will examine a unique combination between wiki-markup and a traditional content management system which seeks to address many of these problems.

Wikis Versus Content Management Systems

Markup syntax itself has a long history in electronic publishing of all kinds of content. The typesetting syntax of TeX and LaTeX offers two good examples of how markup syntax has been used by content experts to control the presentation and publication of media rich content for print. More recently, Web developers are likely familiar with XML as a markup syntax which enables the platform-neutral transmission of datasets and meta-data over the Internet. Many Wikis – notably MediaWiki – make use of markup to help format and structure Web content for easy display on-line.

One hallmark of the wiki movement is a content philosophy which encourages the public editing and correction of any page on the site. Coupling this feature with the ability to create and control the structure of information by creating new pages and menus provides less control than most museums would desire for their primary Web site. Even so, Wikis provide an effective way to allow large numbers of authors to collaborate on the organic creation of content. In part due to their inherent flexibility and lack of formalized content structure, many wikis eschew a graphically polished and stylized presentation of content. Despite the fact that many wiki platforms feature plug-in API's and an open-source platform for software integrations and enhancements, their strength lies in collaborative content authoring, not systems integration.

Traditional Content Management Systems (CMSs), on the other hand, focus on the structured management of content elements and the permissions and access required by users to facilitate collaborative authoring. CMS frameworks tend to focus on the flexible display and presentation layers of a Web site, leading to a polished and professional design which many museums require for their on-line presence. Content authoring is typically more limited in the number of authors, stemming from the foundational knowledge of HTML markup and CSS needed to integrate the site content with the visual display or theme of the Web site.

Many Content Management Systems use graphical (WYSIWYG) editors to simplify the task of authoring HTML content. While this can provide a suitable solution for simple authoring tasks, when a more sophisticated presentation of rich-media content is required, the author will soon need more in-depth knowledge and experience with Web technologies. In addition, these graphical editors are notoriously finicky and full of glitches. They also frequently allow users to directly paste HTML from word processors or other sources which may not conform to site standards.

Is it possible to combine the best of both tools? How might we enable the staffs of our museum to more reasonably approach a print-quality presentation in on-line content which they can create themselves. The problem is a daunting one, and not one that will be quickly solved. However, in combining several of the desirable and familiar features from wikis and CMSs we can come close. The following two figures show an example of an article designed and printed in a recent magazine produced by the IMA and distributed to members. The following image shows a reproduction of that same article and an approximation of the layout using only the wiki-syntax and CMS system described in this paper. It should be noted that as a result, the on-line article adheres to the underlying CSS style and design standards consistent across the rest of the Web site.

Fig 1: A Typical Print Magazine Layout from the IMA's publications department

Fig 2: An On-line Reproduction of the Magazine Article using Only the Pseudo-Wiki tool

What is a Pseudo-Wiki?

In our approach, we leverage some of the useful features of wikis and CMSs to improve Web content authoring. The modularity of a CMS allows us to codify the various types of content on the site and to reuse these content elements across pages. Using the CMS’s theming engine also allows us to separate the business logic that creates automatically generated content and formatting from the design elements that create a uniform look and feel.

From the wikis, we borrow the concept of a markup syntax which allows content authors to annotate text using special characters (i.e. **, //, [ ]) thereby controlling the final presentation or display of the content within the page, and managed by the CMS. We make use of the Creole wiki syntax (http://www.wikicreole.org), which seeks to be a universal format for wiki syntax. The goal of the project is to allow Creole-formatted text to be copied between wikis without the need for adjustments to the markup.

The project also made use of the open-source content management system known as Drupal (http://www.drupal.org). Drupal has been used by the IMA and many other museums recently to manage content and provide a modular platform for many types of Web-based applications. In Drupal, a text entry field can be processed using one of a number of input formats. Each format can be configured to use filters provided by installed modules.

To implement our pseudo-wiki, the default format of content nodes in the CMS is set to use the wiki filter provided by the Creole module. In addition, we developed a series of extensions and integrations of the Creole syntax with the museum’s underlying collection and digital asset management system. Similar extensions to the wiki syntax were also developed to integrate rich media features such as embedded images, video, and social media tools. Each of these filters adds one or more wiki elements (e.g. slideshow, artwork) to the list of markup.

In the example below, a content author on the IMA’s Web site can choose to assemble a carousel featuring works of art from the IMA’s collection. Authors simply enter the accession numbers of works to be featured using the wiki syntax.

{{carousel:2004.68, 60.43, 2005.1, 60.75 | Highlights of the Asian Art Collection}}

The result – when the Web page is rendered – shows a JavaScript slideshow which pulls the most up-to-date imagery and collection information from the IMA’s databases. Any changes made to the collection information, photography or the user-interface code which displays the carousel will automatically be reflected on the Web without any intervention from the content author. What the author entered in one line of wiki syntax generated over 100 lines of HTML and CSS code, not counting any source code from the JavaScript user interface.

Fig 3: An artwork slideshow can be created from a list of accession numbers

Design / Presentation Layer Benefits of Pseudo-Wiki's

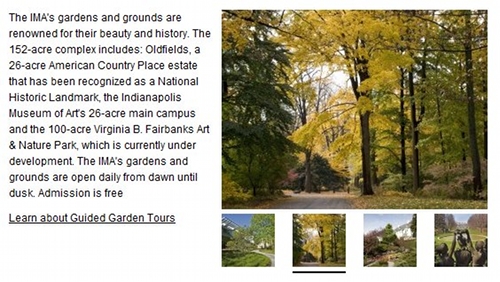

As noted earlier, Wikis are traditionally minimalist in their approach to design and presentation. The main mechanism for arranging content within a page typically includes a hierarchy of headers. To enhance this ability and to more closely match the style and layout of print publications, we added to the wiki a few special extensions which allow content to be laid out into columns. The design of the site makes use of a consistent grid framework across all pages; similar strategies have long been a feature in print design. To ensure consistency with our site design, column widths are always specified in grid units. This allows content authors to think about layout in terms of columns rather than pixels. If, in the future, our site design were to change and the underlying grid changed, the content could remain the same. This strategy extends to the layout of embedded images and other rich media. CMS modules enable on-demand resizing of images according to a set of presets. Users, therefore, never need to go through the trouble of resizing their media content, and the designers are assured of consistency across all page layouts.

These features required modification to Creole's image element. In Creole syntax, an image is included as:

{{filename|title}}

The pseudo-wiki markup borrows the double curly bracket markup to specify special elements using the format:

{{element_name:argument1|argument2|...}}

Each element requires a different set of arguments, but in general the first argument is a comma-separated list of references to entities to be inserted (e.g. images, a video, works of art). The second argument is generally a comma-separated list of key-value pairs that specify layout settings or widget arguments.

For example, to add an image of balloons to a content area, the image is first attached to the page being edited. Then, the image can be given a title of "Balloons" and a description (which is used for html title text). The image can then be inserted into the content as:

{{image:Balloons|width=5}}

When the page is rendered, the image is fetched from the attached files and resized to a five column width. The resulting scaled image and the html generated is cached by the CMS for improved performance.

Fig 4: An automatically generated JavaScript slideshow from Wiki Syntax

Why Not WYSIWYG?

Many content management systems and some wikis support a What-You-See-Is-What-You-Get (WYSIWYG) user interface for content entry. These interfaces have been popular for quite some time, and are generally targeted at non-technical content authors who are somewhat less comfortable with HTML and CSS markup. When it comes to design, WYSIWYG is an all or nothing proposition... either you see what you get, or you don't. Many of these widgets do a good job allowing authors to enter text and simple formatting. However, when authors want a more sophisticated ability to control the layout of a page, or wish to integrate or embed a variety of media, problems occur. Aligning content elements to our grid layout and supporting special features like slideshows were not likely to be reliable enough for our content authors. Because of the flexibility demanded by our design and layout needs, the design of a WYSIWYG interface in this instance was unreasonable.

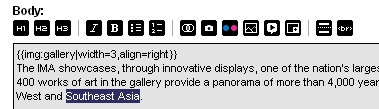

No one will pretend that Wiki syntax is intuitive or easy to pick up, but the learning curve and associated benefits already discussed led us to accept the learning curve needed to bring our authors up to speed on how to use a wiki. To aid our content creators in authoring wiki syntax, we designed a set of shortcut buttons. Clicking some of these buttons inserts wiki markup at the cursor location, and others present dialogs that include fields for the various values that a wiki element supports. After the form is submitted with the desired values, markup is generated and inserted at the cursor.

Fig 5: Traditional WYSYWIG Helper Buttons Used to Author Wiki Syntax

As an additional aid, the wiki syntax is validated as it is converted to HTML. If an argument is not valid, the editor is presented with a message indicating the problem. The validation process also normalizes user-entered data into to the values recognized by the template layer (e.g. "left", "C", or "Right" convert to "left", "center", or "right" for an alignment field).

User Feedback

As was noted earlier in this paper, this pseudo-wiki system was used for all the content authoring for the IMA's recent Web site redesign (http://www.imamuseum.org). During that process a cross-departmental Web team was responsible for all the content creation. This included the formatting and inclusion of images, slideshows, and embeds of video and photosets.

In all, 17 staff members from the IMA contributed to the authoring of this site, including 2 from education, 4 from public affairs, 1 curator, 4 from new media, and 6 technical staff. Of these, only the technical staff had any significant knowledge of HTML / CSS, and technical staff focused mainly on software development and not content entry.

The group succeeded in using the pseudo-wiki to good effect and in including a rich set of images and media across many areas of the site. Most were completely new to any kind of wiki-syntax, and initially found it strange and a bit intimidating. Several felt that the syntactical requirements of the wiki were comparable to authoring simple HTML. In reality, the complexity of the resulting pages could not have been accomplished by the same group of users given a similar amount of training.

Moving to wiki syntax from HTML was a little odd a first, but after using it I understand why this would benefit a less experienced Web user. The templates and editor buttons were straightforward and easy to use – and proved really helpful if I was ever confused. Understanding the grid approach to page layouts was key to manipulating content, and I found the grid diagrams extremely helpful when creating new or editing existing pages. The wiki also allowed me to develop a new section called Tag Tours that made it easy to build custom sets of art that crossed our entire collection and existing social tags. The wiki syntax for this was extremely simple and produced an elegant, professional looking page. Overall, the wiki approach allowed me to take control of content and make decisions without constantly harassing our software developers.

(Daniel Incandela – Director of New Media)

Most reported that cheat sheets and syntax helpers like buttons and syntax widgets allowed them to use the tool much more easily. While similar helper tools were provided for more complex multi-column formatting, these features were rarely used on the site. This is partially due to the chosen design direction of the site, but also due to complexity.

Wiki Syntax is easy to learn. For those who know nothing about Web design or code, wikis are a good tool to simplify the process of creating and designing Web pages. At the IMA, I’ve noticed that it has freed up the Web designer from the routine detail work of content management and allowed him to focus on the big picture. Wikis are an efficient solution for the non-technical members of our Web team (like me) and provides us the opportunity to do more.

(Meg Liffick – Assistant Director of Public Affairs)

A larger roll-out to more staff within the museum will begin in the spring of 2010. It is the desire of the museum’s Web team to allow curators, conservators, librarians, and educators to author content more freely in their own areas.

Changes and Improvements

As we look to ways we might improve this approach, the following elements stand out as ways to start. Continuing to address the unfamiliarity with markup systems in general and wiki syntax specifically, it seems that offering improvements on the shortcuts currently offered will be important. Some of what seems overwhelming to authors is the visual complexity of the text entered into the wiki. Color syntax highlighting of the wiki text is a strategy which has proven effective for computer programmers to visually distinguish functions from variables and comments, and to offer more visual structure to an abstract computer language. Similar strategies for adding syntax highlighting to the wiki tool may help users to segment the syntactical decoration of the wiki from the content of the page. Live previews or side-by-side viewing may also offer a visual check-step that the content being entered results in the intended layout.

As more and more authors come on board and the pace of content creation accelerates, there is a concern among the Web team about how the content process will be maintained and monitored. To some degree, there is a consensus that text authored by professional staff about their own domain should stand on its own; we do want to maintain a quality assurance step to catch any errors in syntax or communication. As discussed above, one of the strengths of Content Management Systems lies in their ability to manage users and roles. The team will likely leverage concepts called Triggers and Actions which are implemented as part of the Drupal CMS. In doing so, we will create an approval process for nodes of content whereby members of the Web team will control the approval and publication of content authored by other museum staff.

One problem that doesn’t have an obvious solution is how to manage the menu tree of the Web site as it grows deeper and wider as a result of staff content creation. Our current menu system supports menus which are four levels deep, but it’s possible that many areas of the site will eventually grow much deeper than this. How that navigation and menu structure will be handled is a decision that will need to be made sometime in the near future.

Conclusions

In this paper we’ve show how a hybrid use of features from wikis and content management systems can result in a dynamic and rich museum Web site that affords staff the ability to author substantial amounts of content while at the same time preserving the flexibility and design polish needed by the professional Web developers and designers. We’ve shown that wikis or CMSs on their own do not provide the flexibility to succeed in this approach over the long term, and made an argument that current WYSIWYG interfaces do not provide content authors with the power to create complex layout. It is out hope that by continuing to improve on this approach, we will be able to create engaging and beautiful Web sites that leverage the dynamic content produced by our museum while formatting and preserving that content in a way that can be reused no matter what the future of technology brings for the field.