Introduction

The enormous popularity of computer and videogames (Lenhard et al., 2008), and the inherent pedagogical qualities of such games (Gee, 2003, Squire et al., 2003) has inspired many efforts to create games that successfully fuse compelling gameplay with learning goals. While most of these efforts focus on formal education, a growing number of museums, zoos and aquariums have undertaken game-based learning projects, as indicated by the addition of a "Games" category in 2007 to the American Association of Museum's MUSE Awards. Yet evidence of the effectiveness of game-based learning, especially in free choice settings, has been elusive.

This session examines one such effort. WolfQuest is a 3D wildlife simulation game developed by Eduweb and the Minnesota Zoo, and distributed on-line as a free download for Mac and Windows computers. Funded by the National Science Foundation, WolfQuest was designed to bring the immersive, emotionally compelling qualities of commercial videogames to informal science learning. In this paper, we will present results from our summative evaluation of learning outcomes that the game produced, discuss the theory behind the project, and reflect on our experiences developing the game: what went as we expected and what surprised us along the way.

WolfQuest and Game-based Learning

From the start, we envisioned WolfQuest as a pilot test for recent research and thinking about games and educational psychology. While this field had been drawing interest from scholars for many years, it received a jump start with the 2003 publication of James Paul Gee's book, What Video Games Have To Teach Us About Learning and Literacy (2003). In many ways, we were directly inspired by Gee's ideas in the design of WolfQuest. Gee articulated 36 learning principles exhibited by good games. Many of these clearly derive from learning theories by Piaget, Vgotsky, and others (Quintana, 2005). Here are several examples (all principles from Gee, 2003):

- Active, Critical Learning Principle: All aspects of the learning environment are set up to encourage active and critical, not passive, learning. In WolfQuest, the 3D environment (an accurate model of four square kilometers of Yellowstone National Park) features elk, grizzly bears, stranger wolves, and small mammals, all of which interact with players in different ways, requiring active exploration and experimentation.

- “Regime of Competence” Principle: The learner gets ample opportunity to operate within, but at the outer edge of, his or her resources, so that at those points things are felt as challenging but not “Undoable.” Survival in WolfQuest is challenging (killing a single elk can take ten or more minutes of persistent work) but achievable, with the difficulty increasing as the player progresses through the game.

- Probing Principle: Learning is a cycle of probing the world; reflecting in and on this action and, on this basis, forming a hypothesis; reprobing the world to test this hypothesis; and then accepting or rethinking the hypothesis. In WolfQuest, players interact with stranger wolves through a turn-based dialog system, where they can see the results of different messages (displayed in English but conveyed in-game through wolf postures and vocalizations), learning through experimentation about wolf social hierarchies.

- Dispersed Principle: Meaning/knowledge is dispersed in the sense that the learner shares it with others outside the domain/game, some of whom the learner may rarely or never see face-to-face. Players share experiences, strategies, and goals in on-line multiplayer games and the discussion forums.

- Affinity Group Principle: Learners constitute an "affinity group," that is, a group that is bonded primarily through shared endeavors, goals, and practices and not shared race, gender, nation, ethnicity, or culture. WolfQuest's affinity group began to form even before the game launched and has far exceeded our hopes in making both multiplayer and discussion forums into vital components of the project.

Gee's work focuses on high-budget commercial video games, which bear limited resemblance to the simple games and game-like quizzes, puzzles, and other interactives most often developed by museums. Indeed, this was another of our goals for WolfQuest: to develop a game complex and sophisticated enough to incorporate Gee's learning principles. In doing so, we hoped it would also be sufficiently sophisticated (functionally and visually) to compete with commercial games for the attention of our primary audience of ‘tween and teenage gamers.

WolfQuest: Game, Community, and Network

WolfQuest has three components that work together to reach and engage our primary audience of 9-15 year old game-playing youth.

- Game: In an immersive 3D game environment, players take on the role of a lone dispersal wolf in Yellowstone National Park trying to find a mate, or in multiplayer mode, join a wolf pack made up of friends or other players. Through trial and error, instinct, and experience, players must learn how to hunt elk, cooperate with packmates, interact with stranger wolves, and compete with scavengers. Gameplay is designed to encourage players to exercise critical thinking and inquiry skills as they develop successful strategies, and develop a strong emotional connection with wolves, influencing their attitudes toward wolves and habitat conservation in the real world.

- On-line Community: The WolfQuest game serves as a catalyst for a self-sustaining community of learners. Discussion forums (a standard feature of videogame sites) foster social learning amongst players as they share their experiences with wolves and nature inside and outside of the game, strategies and tips for playing the game, game-inspired art and stories, and tangential discussions typical of any affinity group. The discussion forums also connect players with wolf experts, allowing for exchange of information and questions outside of the game. The WolfQuest Web site also offers background information about wolf ecology and conservation, and educational materials for classroom use.

- National Network: WolfQuest's impact is greatly expanded by a network of zoos and similar institutions involved in wolf education and conservation. All of these promote the game on their Web sites and in local marketing efforts to extend the reach of the project. Each also offers on-site wolf-related programming to entice players to visit and experience wolves in the real world.

Fig 1: Screenshot from WolfQuest game

Topic-centric, not institution-centric

Unlike most on-line museum projects, we intended the game to have its own identity, with its own domain name, rather than branding it within the Minnesota Zoo's identity. Our rationale was partly hubristic (thinking we could create a game worthy of its own brand) and partly altruistic: we wanted to share the game with zoos around the country. By letting them feature the game on their own Web sites and market the game to their regions, they might then attract game-players to their own on-site wolf programming. Each partner institution has its own branded URL (e.g. nationalzoo.wolfquest.org) that features information about its own wolf exhibits and programming along with the regular sections about the game, wolf ecology, and the on-line community. As a result, WolfQuest has a much weaker association with the Minnesota Zoo than the typical on-line museum project, and zoo visitation that directly results from the game is likely too small to measure. (In fact, we haven't even tried to measure it.) The project is topic-centric rather than institution-centric, since our goal is for players to extend their learning beyond the game in any type of wolf- or nature-related experiences.

Audience Impact

The first measure of success of a learning game is: Does anyone want to play it? WolfQuest has succeeded on that level. The game launched on December 21, 2007 to an unexpectedly attentive audience. About 4,000 users downloaded the game in the first few hours after launch, bringing down the server and requiring a midnight switch to a dedicated server to handle the load. In the 14 months since the game launched, over 250,000 people have downloaded the game. Players initiate or join over 30,000 multiplayer game sessions per month. The game’s on-line community has over 37,000 registered members who have made nearly 600,000 posts to the forum, with a current average of 1,200 posts daily. Players have even created their own gameplay videos and posted them on YouTube (over 350 to date). The game has definitely found, and retained, an audience.

Of course, the ultimate measure of success is: Do players learn anything close to what the developers intended them to learn? WolfQuest ambitiously promised not only to fuse the real world of wolf biology with addictive gameplay, but to teach players something substantive about wolves as well, to inspire players to think about larger issues of wolf and wildlife conservation, and ultimately to engage in real-world conservation behaviors like visiting a zoo or nature center. Our summative evaluation finds that those things are indeed occurring.

In a summative evaluation of on-line resources, sampling is always a concern. For this evaluation, we took a mixed-methods approach, employing three different methodologies: a large-scale Web-based survey, telephone interviews of players, and content analysis of the forum discussions. The vast majority of the data presented in this paper is from the Web-based survey. Our main evaluation goal was to determine whether playing WolfQuest, and visiting the Web site and/or forum:

- increased knowledge of, and interest and attitudes towards wolves;

- increased intended or actual wolf-related conservation behaviors; and

- supported or reinforced scientific habits of mind.

Evaluation Sample

Web survey participants were recruited through invitations posted on the WolfQuest Web site and community forum, and in the 17,000-subscriber WolfQuest newsletter. While the Web site and forum links bias the sample to current and devoted players, the newsletter reached youth who may not have played the game for many months, and helped balance the sample toward a broader range of players. There were 964 valid responses received to the on-line survey, representing players from every state in the union and 48 other countries. (The US and Canada accounted for just over 75% of the survey respondents; 63% of all WolfQuest players reside in the US and Canada.) The game successfully reached the target audience, as 67.2% of the participants were ages 9-15, and another 17.4% were 16-18. A total of 85.6% of the respondents were age 18 or under. Median age was 14 years old.

Respondents were daily video game players, including 51.3% of the target 9-15- year-olds who were daily computer or video game players. According to the Pew Internet and the American Life Project, 50% of American teens age 12-17 and 21% of adults over age 18 play computer or video games daily. (Lenhard et al., 2008, MacGill, 2008)

| Response Category | Percent |

|---|---|

Less than once a week |

8.6% (n=83) |

1-3 times a week |

22.5% (n=217) |

4-6 times a week |

21.9% (n=211) |

Everyday |

47.0% (n=453) |

Table 1: How Often Do You Play Computer or Video Games?

WolfQuest players tended to play often. While nearly half of our sample was playing the game for the first time when answering the Web survey, the vast majority of the others had played WolfQuest frequently.

First time playing |

Played 2-3 times |

Played 4-6 times |

Played 6-11 times |

Played more than 11 times |

|---|---|---|---|---|

42.7% (n=402) |

4/6% (n=43) |

5.2% (n=49) |

8.7% (n=82) |

38.8% (n=365) |

Table 2: How Many Times Have You Played WolfQuest?

There is a significant literature emerging on the appeal of gaming and the different types of game players (see the Bartle Test: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartle_Test). While not central to the evaluation itself, we were curious to see how WolfQuest players would be defined within established typologies of game players. Using Bartle’s taxonomy of game-players (1996), we asked participants to pick a statement, based on Bartle’s work, which best matched how they play computer or video games. Each of these statements links with a type of player, as can be seen in Table 3 below. While Bartle recognizes that these traits are “stereotypes” and that any individual player may embody multiple traits in multiple settings, it is revealing that overwhelmingly WolfQuest players described themselves as Explorers. Intuitively, it makes sense that WolfQuest would appeal to this type of gamer; it is not a first-person shooter, and while there are goals to achieve, it is not a game with a significant emphasis on levels or points. This is an important point for institutions that are concerned that today’s youth only respond to first-person shooter games.

Statement about preferred game play |

Type of player |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|

I am most interested in mastering the game and scoring the most points. |

Achiever |

7.5% (n=72) |

I am most interested in discovering new parts of the game and creative ways to advance through it. |

Explorer |

76.6% (n=738) |

I am most interested in getting to know other people like me who play the game. |

Socializer |

13.8% (n=133) |

I am most interested in attacking as many other players as possible. |

Killer |

2.2% (n=21) |

Table 3: Preferred type of game play

Knowledge Increase

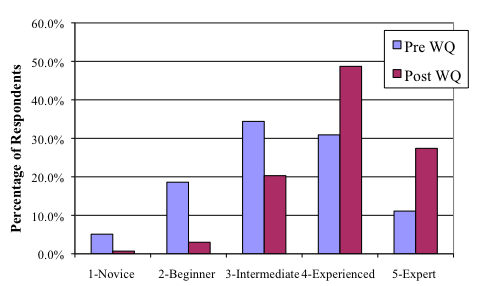

In monitoring the WolfQuest forums, it was clear that the game had a following of individuals who were passionately devoted to wolves. While it is possible to change the knowledge, attitudes and behaviors of those who were already wolf devotees, we wanted to find out how the game affected players with less initial interest in wolves. In the Web survey, we asked individuals to self-rate their knowledge of wolves, their behaviors, and their habitats prior to playing WolfQuest. A significant number of individuals (42%) rated their wolf knowledge as experienced or expert, but as a whole, the rating for pre-knowledge fell along a rough normal curve.

1-Novice |

2-Beginner |

3-Intermediate |

4-Experienced |

5-Expert |

|---|---|---|---|---|

5.1% (n=48) |

18.6% (n=175) |

34.4% (n=324) |

30.9% (n=291) |

11.1% (n=105) |

Table 4: Self-Rated Prior Wolf Knowledge

We also asked players to self-rate their knowledge of wolves, their behaviors and their habitats after playing WolfQuest. There was a definite cognitive gain with a median change score of 1 point on a 5 point scale (Standard deviation of .784).

1-Novice |

2-Beginner |

3-Intermediate |

4-Experienced |

5-Expert |

|---|---|---|---|---|

0.7% (n=7) |

3% (n=28) |

20.3% (n=191) |

48.7% (n=459) |

27.4% (n=258) |

Table 5: Self-Rated Post WolfQuest Wolf Knowledge

Chart 1: Comparison of Average Pre- and Post-Game Knowledge

To see whether these claims of higher knowledge were true, we asked participants a variety of questions about wolves, including what specifically they had learned about wolves from the game. Participants provided a range of up to five responses related to habitats, hunting behaviors, territories and threats to wolf survival, social behaviors, and other wolf facts related to the anatomy and species of wolves. Out of a representative subsample of individuals who took the survey (n=280), 198 individuals responded to this open-ended question. Only 3% of those respondents indicated that they did not learn anything new from playing the game. Sample responses to this question include:

"Hunting is actually quite difficult. Wolves have to contend with other predators. Wolves don't always eat their entire kill.”

“Aggressive behavior varies from pack to pack. Taking down an elk alone is hard. Grizzly bears are a big threat to wolves. Howling can call your mate to you. Wolves are good jumpers.”

“Wolves are very social. They need large hunting grounds.”

“Wolves have to eat alot in order to live. Look for weak prey. Don't mess with Grizzlies. Wolves must travel far to survive. A wolf can survive on an elk for days.”

WolfQuest had an impact on the learning of the majority of players (n=182 of this subsample of 280), with evidence found by both specific and general recall of facts and knowledge (See Table 6).

Response Category |

Percent (n=182) |

|---|---|

Social Behaviors |

116.0% (n=217) |

Hunting |

79.1% (n=148) |

Defense/Territory |

45.5% (n=85) |

Other Wolf Knowledge |

46.0% (n=86) |

Habitat |

18.7% (n=35) |

Affective/Experiential/Social/Behavioral |

13.4% (n=25) |

Humans (of and related to) |

2.1% (n=4) |

Table 6: What are some things you learned, or found out, about wolf behaviors and habitats from playing this game?

*Percentages total more than 100% due to multiple responses, 3.2 responses on average

Greater Connection to Wolves

Players also reported a stronger emotional attachment to wolves after playing the game. Over three-quarters (75.6%) of the respondents felt the game made them more emotionally connected to wolves. Emotional connection had a statistically significant negative correlation with incoming self-ranked knowledge, so that individuals who ranked themselves as experienced or expert were less likely to report that WolfQuest increased their connection to wolves. This is an expected finding, as these individuals were likely to feel highly connected to wolves prior to playing the game.

1-Novice |

2-Beginner |

3-Intermediate |

4-Experienced |

5-Expert |

Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

75.0% (n=36) |

85.7 % (n=150) |

79.3% (n=257) |

70.4% (n=205) |

61.9% (n=65) |

75.6% (n=713) |

Table 7: Post WolfQuest Connection to Wolves by Incoming Knowledge Level

One ten-year-old, self-ranked as previously a novice, said when asked why s/he felt more connected to wolves, “I know more about them, I used to think wolves were mean and ugly from movies, but now I know what they are like and I feel more like I can help them to survive in this world.”

Scientific Habits of Mind

One of the key evaluation questions regarding WolfQuest is about the use of critical thinking skills throughout the game. As mentioned earlier in this paper, James Gee and others have discussed the skills involved in and supported by good gameplay. Steinkuehler and Duncan (2008) have applied the concept of scientific habits of mind (including, for example, model-based testing, social construction of knowledge, and use of evidence) to the commercial game World of Warcraft. Their analysis was based on forum postings within the game. While we are currently analyzing WolfQuest forum posts using a version of the Steinkuehler and Duncan coding categories, we also directly asked participants what sort of challenges they faced within the game and how they overcame those challenges. Though this data is preliminary, respondents showed clear evidence of scientific habits of mind throughout their responses. They made predictions about what hunting and mate-finding strategies might work, tested those predictions, analyzed the results, using observation and note-taking skills, and collaborated with others to devise new techniques. All of these responses support the extensive, systematic use of scientific habits of mind throughout the playing of WolfQuest. Participants responded with statements such as:

“Well, at first, I was a very terrible hunter. I mean. I was pitiful. I couldn't even take down the weakest elk in the herd, even WHEN I had a mate! It was a very sad sight to see. Well, to overcome such a problem, I just kinda practiced. And watched a few videos that people had made. And... Well, I made a few observations myself. And you know what... it worked! I kinda just practiced, watched my status bars and stuff, took notes.”

“I had to overcome speed, and the trouble with the social behavior. I also had to keep up with hunting, and trying not to die. Survival of the fittest. I tested being dominant over the stranger wolves, and how to save energy for hunting. Once I found a mate, everything got easier and more easier.”

“To use the right body language to kill/ make friends with other wolves. Knowing which reply to make is important–never give the other wolf a chance to attack. Hunting elk–never run full charge willy-nilly at the whole herd. Wait until one is separate. Try different things and record what data worked best.”

Some players used the multiplayer mode specifically to address game challenges.

“Well, I also took a bunch of information and tips from my friends. I watched them hunt the elk, and saw their strategies. And combined them, along with what I saw on the videos and from my own observations, together to make my own awesome strategy to hunt.”

Wolf-Related Behavior change

Within the scope of the Web survey, we asked players what sort of activities and behavior they engaged in as a result of their WolfQuest experience. Behavior change is a notoriously difficult outcome to achieve for many projects, so we designed our survey to solicit both actual activities and the intention to do those activities, with follow-up currently underway to parse the difference and distinguish any overreporting (Friedman, 2008).

Overall, large percentages of players showed intentions of doing other wolf-related activities, including such further explorations of wolves on the Internet, in books and on television.

| Response | Percentage |

|---|---|

Look up information about wolves on the Internet? |

84.2% (n=797) |

Watch a TV show or video about wolves? |

83.8% (n=792) |

Read about wolves in books, magazines, or newspapers? |

82.6% (n=781) |

Talk to friends or family about playing the game? |

82.2% (n=778) |

Talk to friends or family about wolves? |

78.4% (n=742) |

Make art related to wolves? |

76.3% (n=722) |

Visit a zoo? |

72.5% (n=686) |

Visit a nature center, state park, or wilderness area to see wildlife? |

69.3% (n=656) |

Participate in outdoor activities, such as hiking, fishing, birdwatching, etc.? |

67.0% (n=634) |

Visit a wildlife area to see wolves? |

62.3% (n=589) |

Write something about wolves or wolf habitats? |

58.7% (n=555) |

Create a wildlife friendly backyard garden? |

42.2% (n=399) |

Plan a school project related to wolves? |

41.1% (n=389) |

Attend a wolf class or program at a zoo or nature center? |

38.4% (n=363) |

Table 8: Due to playing WolfQuest, have you done or do you intend to do any of the following….

These percentages are high enough to raise concerns about overstating the impact of the game, yet the commentary from the players when asked to list any other activities they had done due to WolfQuest demonstrates their deep connection to the game. It is enormously difficult to represent the variety of answers in just a few quotes; Table 9 below shows some of their responses (and includes age and incoming self-rated knowledge level). The variation in incoming knowledge level shows that even those individuals who considered themselves to be “beginners” in terms of wolf knowledge before playing the game aspired to, or had already engaged in, significant activities and expressions of values about wolves as a result of the game.

In addition, the more that individuals played the game, the more likely they were to report doing or intending to do the above behaviors. Only two activities - creating a wildlife friendly backyard garden and visiting a nature center, state park, or wilderness area to see wildlife - did not show statistically significant differences between casual players and those that played WolfQuest more than ten times.

Responses |

Age |

Incoming Knowledge level |

|---|---|---|

Made paper wolfs. And I like acting like one in my yard. |

7 |

3 |

I've made up a wolf game with my friends at school |

9 |

1 |

I’m planning to clean up forests and make it a better home |

10 |

4 |

Fund raiser |

10 |

2 |

Pretend to be a WOLF on the nature trail! |

10 |

4 |

I colored pictures of wolves from books |

10 |

2 |

I have planned to visit the Minnesota zoo and go to Yellowstone National Park. |

10 |

1 |

I might go to Ely, MN to the International Wolf Center this summer!!!!!!!!!!! |

10 |

3 |

I plan to convince the world (or neighborhood for now) that wolves are not mindless animals but are beautiful and magnificent creature, I also am making a petition to stop the killing of wolves and to start building wolf habitats. |

10 |

2 |

I plan to go to Yellowstone next summer with my best friend who also loves wolves and plays WolfQuest. |

10 |

3 |

I have seen the world the way wolves do. |

10 |

0 |

Make a website about them |

10 |

4 |

Wolf for Halloween, painted a picture, watched a documentary |

10 |

2 |

Tried to raise money for wolves by making little boxes saying "save a wolf £1" |

11 |

2 |

I am planning to put posters up around my school about WQ |

11 |

1 |

Go camping in the wilderness maybe |

11 |

1 |

Talk about wolves (I talk A LOT by the way) |

11 |

1 |

I draw pictures of myself in the game. (I am a pure white wolf called Mist) |

11 |

2 |

"Adopt" a wolf and support it in the wild |

11 |

4 |

I started keeping a journal about the elk population in Yellowstone. |

12 |

3 |

I am planning to help wolves by donating to my local zoo and getting others to, also, because I think wolves are a great educational animal. |

12 |

3 |

My family and I went to Yellowstone over the summer, and I was able to see the areas that the game is based in (Slough Creek, Specimen Ridge, Druid Peak, Lamar Valley, etc.) |

13 |

1 |

I talked to Dave Mech (a biologist) about the game and correspondingly about the Yellowstone wolf project |

13 |

3 |

I have redecorated my bedroom so it is completely about wolves. |

13 |

3 |

Raised Money for Wolves through a lemonade stand |

13 |

0 |

I've signed up for a voluntary job at an injured wolf rehabilitation center. |

13 |

3 |

Well I did a speech on why they should not shoot wolves in Alaska... my class loved it and so did my teacher |

14 |

1 |

Go to a wolf center like here in Colorado or in Mission: Wolf. Guess what? We now have wolves in the four-mile area! So close to me! I heard them howl! I'm so EXCITED! |

14 |

3 |

I wrote a speech about the yellow stone wolves for debate and will be taking it to competitions |

15 |

3 |

Table 9: What Other Wolf Activities Have You Done Due to Playing WolfQuest?

Learning from WolfQuest

While the evaluation is still underway, these initial results show that WolfQuest has been highly successful in all three areas under review - increasing knowledge of, and interest and attitudes towards wolves, increasing intended or actual wolf-related conservation behaviors, and supporting or reinforcing scientific habits of mind. These results should allay fears and skepticism (encountered during WolfQuest development) of some environmental educators over the use of a videogame as a tool for science learning. In our experience, other professionals within the field have articulated concerns that young players do not, as a rule, significantly engage with a game if the game has a clear educational agenda. These fears can also be laid to rest.

While we recognized the above fears and concerns, we did not share them. Instead, we had an entirely different set of concerns and expectations as we began development in 2006. Some of these were based on our prior experience, while others drew on work by Gee and other researchers. As always, actual experience bore out some of our expectations while taking us by surprise in other ways.

Some Expectations Confirmed...

- Wolves are a good match for action gameplay. Not every topic of importance to a museum, zoo, or aquarium is suitable for a game. Because games employ an underlying system of rules, subject domains in science and history (which follow the rules of nature and society) generally present more natural topics for game design than art, with its emphasis on expression and interpretation. We expected wolves to be an ideal subject for a game. In fact, we chose wolves for that very reason. Wolves live the lives of action heroes - exploring and defending territories, attacking elk, skirmishing with grizzly bears, and sneaking onto cattle ranches. While the actual game design required a great deal of work to balance game mechanics and content accuracy, the overall outline of the game came easily and meshed well with established audience expectations for gameplay.

- Modern software allows small teams to produce compelling, commercial-grade games. Our original plan was to use Shockwave 3D for a browser-based game, but by the time the National Science Foundation awarded us the grant, we had upgraded our plan and ambitions by adopting Unity, a powerful new software authoring and publishing tool for game development. With Unity, a small team can produce a sophisticated and gorgeous game. Our core development team (project director, coordinator, game producer, game designer, programmer, visual designer, and of these only the coordinator was full-time on the project), plus outsourced 3D artists, was large enough to produce several hours of high-quality gameplay and visual assets.

- Go where the kids are. Having defined our audience as "game-playing youth age 9-15," we deliberately avoided traditional museum outreach channels to youth, such as teachers. Instead, we wanted to plant our flag directly in youth-centric digital culture. The game itself is the most obvious product of this approach. To attract players, we used both traditional and viral marketing. By far the most successful marketing happened virally, entirely outside of our control. Our two-minute teaser video, developed for fundraising and put on the WolfQuest Web site long before the game launch, caught the attention of several gaming Web sites, and was soon featured (albeit with some mockery) on the popular cable TV program "Attack of the Show." Nearly overnight, our site traffic skyrocketed, jumping from 500,000 hits in July 2007 (mainly from our active forum members) to nearly 10 million the following month - still five months before the game launched. Clearly, we had succeeded in reaching youth on their home territory.

- Ancillary activities are essential elements in the game-based learning process. Many of Gee's principles involve activities outside of the game itself, most notably in discussion forums where players share knowledge and experiences with their affinity group. The game mechanics allow a variety of hunting and survival strategies, few of which are explained in the official documentation so as to encourage on-line discussions about them. While we were certainly lucky to have an enthusiastic community form spontaneously around the game, we actively focused their discussions on both gameplay and larger issues of wolves in the wild. This soon made the forum into the most effective pedagogical component of the entire project. Along with discussions about wolves and the game, the forum allows users to explore wolves in other ways, such as by sharing original artworks (over 450 pieces submitted) and stories about wolves.

- Games can influence subsequent behavior. Behavioral impacts are notoriously difficult to achieve, but we believed that a good game can be compelling enough to affect subsequent behavior. Initially these goals were modest: we hoped players would learn more about wolves from the Web, books, TV programs, and by visiting their local zoo. During development, we made behavioral outcomes a primary goal and developed a list of conservation behaviors based on current research in the field. We expected only a small percentage of players to exhibit these behavioral outcomes, but our initial summative results indicate the game and community do influence the behavior of some players in exciting ways.

...And Some Surprises

The unexpected is inevitable in a project of this scope and complexity. What surprised us most during development?

- 3D games are very, very hard to make. Despite a decade of experience developing digital learning games and interactives, we recognized from the start that WolfQuest would be more challenging than any previous project. Yet we still underestimated the difficulty. While we had dabbled in 3D previously, creating a fully-realized 3D world was a crash course in polygons, textures, shaders, and the myriad graphics capabilities of computers, all of which require mastery in order to create a 3D world that runs on the majority of home computers. Furthermore, designing and programming a robust ecological simulation, complete with artificial intelligence and gameplay code to accommodate untold combinations of user choices, requires a level of software architecture and design that we had not previously produced. And finally, shifting from Shockwave to Unity tempted us into a dramatic upgrade in production values, well beyond what we had designed our budget to accommodate. For all these reasons, by the time we launched the final game update in July 2008, we had gone 40% over our $275,000 game development budget. Not only was this painful financially, but it also constrained our ability to further polish and support the game.

- Suspension of disbelief is a fragile thing. We designed the 3D game world and ecological simulation, both visually and behaviorally, to create a suspension of disbelief in the player. This was a departure from our 2D Flash games, which have a sufficient level of abstraction to allow many shortcuts, from iconic representations of real-world entities to popup windows that explain what is too difficult, time consuming, or just plain expensive to show. We had few such shortcuts available in our 3D world. If an elk did not react naturalistically to an approaching wolf, we could not distract the user with a popup window. If the foreground grass did not blend seamlessly to the surrounding skybox, we could not cover it up with a convenient graphic design element. Suspension of disbelief, a basic expectation of players in a 3D game world, is laboriously created, yet easily fractured, and it took hundreds of hours of fine-tuning to achieve a reasonably believable world.

- On-line

communities are waiting to form around some topics. Perhaps the most

astonishing aspect of WolfQuest has been the audience response, which

surpassed our highest hopes. We knew that wolves, as charismatic megafauna,

held a strong appeal for our audience, but we did not expect an affinity group

to come knocking even before launch. This group formed when a few teenagers saw

an early press release from the Minnesota Zoo and posted links to our site on Zoo

Tycoon and My Little Pony game forums. By July 2007, five months

before our scheduled launch, we had lively discussions on our developer's blog

(http://www.wolfquest.org/wordpress). One blog post, about our struggle to

balance fantasy and reality in the game design, prompted 347 comments. Given

this response, we launched the WolfQuest discussion forum ahead of

schedule. It quickly became a true on-line community, with users around the

world befriending each other, encouraging each other, and discussing subjects

of shared interest. In the 20 months since its launch, users (primarily between

ages 10 and 17) have made nearly 600,000 posts on 15,000 threads.

Despite this success, we recognize the challenges of creating a thriving on-line community on many topics. We have worked on many projects that sought but failed to create such a community. We believe it is essential to identify and attract an existing affinity group, rather than attempt to create one from scratch. With WolfQuest, such a group had materialized in the forums of other animal-centric games, but WolfQuest gave them a new place to call home. Such groups, especially among youth, do not exist for many subjects of importance to museums. Thus, a compelling game becomes even more important as an attractor and catalyst for an on-line community. - On-line communities require substantial care and feeding. While our community formed spontaneously and is in some ways self-sustaining, it would not be a successful community of learning without the countless hours our project coordinator has spent guiding on-line discussions, posting provocative research findings on wolf ecology and conservation, and ensuring that discussions remain healthy and safe for our youth audience. Managing this community takes 15-20 hours a week. In addition to facilitating productive discussions, she also must approve new users, discipline and expel users acting inappropriately or "trolling," and manage the team of 18 volunteer moderators recruited to handle the forums during the remaining 140 hours a week. Without this constant effort, the forum would drift off-topic into discussions of videogame releases, favorite science fiction novels and the like. Our project coordinator has also been forced into the role of teen counselor, mediating on-line disputes between users and handling two cases of users with announced suicidal intentions. The importance of this job was never clearer than in the fall of 2008, when our first coordinator left for another job. In the two-month interim until we hired a new coordinator, when the forum was lightly moderated, the quality and educational value of the on-line discussions noticeably declined.

- Real gameplay encourages replay. Many educational "games" (including many of our projects) would more accurately be called "game-like content delivery interactives." As such, they do not encourage replay, since the experience will be nearly identical each time. WolfQuest offers true gameplay: players interact with a dynamic system that responds to their actions based on an underlying ruleset. As such, each game session is different, encouraging replay. With our budget restrictions, we were able to create only a two- or three-hour game arc. Naturally, this limits the game’s replay value, since there are not that many different things that a player can do. And yet, to our surprise, our summative evaluation found that two-thirds of non-first-time players report playing the game more than ten times. More importantly, the evaluation also found that replay positively correlates to learning outcomes, making replay an indicator not just of a successful game, but of an effective learning game.

- Devotion cuts both ways. It's extremely gratifying to have a core of dedicated players, but their devotion has unexpectedly produced more work on our end, particularly for our project coordinator. These players assume that they have a significant voice in the project. On the forum, they make long lists of new gameplay and content requests and foment rumors to the point of raising unrealistic expectations. Managing their enthusiasm requires a delicate balance of encouragement and reality checks. And many players’ enthusiasm exceeded their computer skills or the quality of their computer hardware. Thus a significant number of project resources was devoted to technical support that was not strictly part of the learning mandate of the project, but which was required to keep players happy. And, in spite of the fact that the game was free, because of the quality of the visual assets and gameplay, users did in fact compare it to commercial games that cost ten or twenty times our budget. In the event of technical problems, this comparison was seldom favorable, although we were also surprised at the number of players with underpowered computers who were willing to endure extremely poor game performance in order to play the game at all.

- Games know no borders. Our hope during development was to reach a nationwide audience. We took geography into account when recruiting our National Network of zoos, ensuring that we had partners in every region of the country. This effort succeeded: the top states for game downloads are California, Minnesota, Texas, Florida, and New York. But we gave no real thought to the audience beyond the United States, so we were surprised to see that nearly half - 44% - of all players lived outside the US. For the most part, this is simply proof of the global appeal of both games and wolves, but it also demonstrates the potential to further expand this global audience through localization (the software industry's term for language and cultural translations).

- It's the players' game, we only created it. The passionate response to the game reveals an existing desire for a wolf role-playing game. During development, we had on-line discussions with players about the balance between fantasy and reality, to make clear our intent with the game. Many players came to appreciate and value scientific accuracy in the gameplay, but many others simply decided to use the game in their own ways in their multiplayer role-play sessions (role-playing being a particular kind of open-ended gameplay that is more narrative in orientation than the strict simulation we have enforced with WolfQuest's design). Since the game’s wolf characters are limited to actual wolf behaviors, most of the interaction in these sessions is through the in-game chat system. These players spin fantastic tales of their wolf-lives and adventures far beyond the scope of either the game or biological realism. We accept this usage (since we can't prevent it), hoping that it deepens players' connection to wolves. Of course, this behavior is hardly unique to WolfQuest. Turning digital and social media to one's own purposes is typical human behavior. But museums must realize that a game, like anything else they make available, is "theirs" only until they release it on the world. At that point, people will take ownership of it, making it theirs in ways that the developers never foresaw or intended.

Whither WolfQuest?

We released the final update to WolfQuest Episode 1: Amethyst Mountain Deluxe, in July 2008. We had always planned on at least one more episode, and finally obtained sufficient private funding for it in fall 2008. Episode 2: Slough Creek, which will feature the most popular player request - pups, is currently in development, to launch in summer 2009. We are also completing the summative evaluation, conducting telephone interviews with players and doing content analysis of forum discussions, to better understand the project's learning outcomes. Our funding provides for a half-time project coordinator through the summer of 2010, to keep the forum healthy and focused for a full year after release of Episode 2.

At that point, WolfQuest will have had a good run and we developers may be ready to retire the project. But our community will likely think otherwise. Thus, part of our challenge this year is to develop a sustainability plan. Can we train teenaged moderators to manage the forum into the future? Some commercial games, abandoned by their makers, have been adopted by an on-line community and sustained for many years, but our 'tween and teenaged audience makes this option problematic. (For example, one of many things that our coordinator does is review faxed parental permission forms for forum registration, to comply with COPPA). Can we find inexpensive hosting for the site? (The forum traffic alone requires a dedicated server, costing $1,000 annually.) Or do we simply shut down the on-line forum - perhaps the most effective pedagogical component of the project - and convert to a static site where new players can only read about wolves and download the game?

Whatever its ultimate fate, WolfQuest has already given us a glimpse of the potential for free choice game-based learning. By engaging youth in their leisure time and inspiring them to continue their learning beyond the game, it demonstrates one way to employ popular media genres and technology to further our educational goals. Not every project will be as well-suited to game-based learning, or have as dramatic outcomes, but it is clear that it is possible to create a credible, real-world game that can successfully compete in the entertainment media landscape.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Science Foundation, ESI grant # 0610427, for making WolfQuest possible.

References

Bartle, R. (1996). "Hearts, Clubs, Diamonds, Spades: Players Who Suit MUDs." Consulted January 26, 2009. http://www.mud.co.uk/richard/hcds.htm

Friedman, A. (Ed.) (2008). Framework for Evaluating Impacts of Informal Science Education Projects. Washington D.C.: National Science Foundation.

Gee, J.P. (2003). What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Lenhard, A., J. Kahne, E. Middaugh, A.R. Macgill, C. Evans, and J. Vitak (2008). “Teens, Video Games, and Civics.” Pew Internet & American Life Project. Consulted January 22, 2009. http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Teens_Games_and_Civics_Report_FINAL.pdf

MacGill, A. (2008). "Adults & Video Games." Consulted January 22, 2008. http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Adult_gaming_memo.pdf

Quintana, C. (2005). “Constructivism and On-line Interactivity.” In Proceedings of Web Designs for Interactive Learning Conference. The Exploratorium/ Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology http://www.wdil.org/conference/proceedings.

Salen, K. and E. Zimmerman (2004). Rules of Play. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Squire, K., H. Jenkins, W. Holland, H. Miller, A. O'Driscoll, K. Tan, K. Todd (2003). “Designing Educational Games: Design Principles from the Games-to-Teach Project.” Educational Technology, 43 (5), 17-23.

Steinhkuehler, C. and S. Duncan (2008). "Scientific Habits of Mind in Virtual Worlds" Journal of Science Education and Technology, Vol. 17, No. 6. (1 December 2008), pp. 530-543.