Introduction

The Web has made it possible for institutions to make collections available on-line to wide audiences. The emerging ‘Social Web’ (often dubbed Web2.0) made it possible for wide audiences to contribute to on-line collections. As a result, users and institutions are beginning to inhabit the same, shared information space. This is an exciting prospect, as we are now witnessing new paradigms for engaging users with our shared heritage.

'Netizens' are using technological advances offered by cultural heritage institutions, publishers and other commercial entities, as well as objects from a great variety of sources, to shape this information space. The new paradigms imply, in many cases, the need for profound change in institutional practice; for instance, using the power of the Social Web to enrich knowledge about our shared heritage. As a result, republication and reuse are enhanced, and thus its value is increased.

We look at the emerging services in the cultural heritage domain which are mapped and clustered according to specific dimensions.

In this paper, we present results of two large-scale pilots (both carried out within the scope of a large-scale digitization project called Images for the Future):

- Waisda? a Video Labeling Game that uses the concept of crowdsourcing to improve access to video archives.

- Gas in Beeld (“Natural Gas in Images”)

Images for the Future

The collections of the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision in Hilversum, the National Filmmuseum in Amsterdam, and the National Archive in The Hague safeguard the memory of the Netherlands as captured in moving images over the past hundred years. As demonstrated below, the collections represent great social and economic value – if and when they become accessible.

Large-scale migration of analogue audio-visual material for preservation and access is exceptionally expensive. For Images for the Future it involves the selection, restoration, digitization, encoding and storage of 137,000 hours of video, 20,000 hours of film, 124,000 hours of audio, and more than three million photographs. The total costs are estimated to exceed 170 million Euros.

Migrating from analogue to digital is only the beginning. To make the material truly useful, investments will have to be made to enrich the existing metadata so that they can meet the requirements for use. Also, services will have to be developed to make the material meaningful and useful for a variety of user groups. Educational institutions, students, teachers, publishers, television and film makers, Web designers, graphic designers, artists, software developers, Internet providers, museums, theatres, heritage institutions, libraries, etc. will all profit from content becoming digitally available and accessible over networks.

Emerging Practices in the Heritage Domain

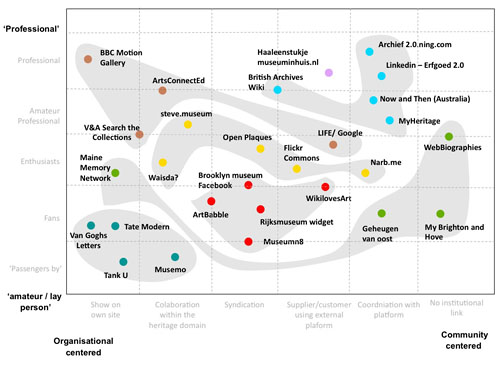

Figure 1 (below) introduces a model used to map out the variety of services that are currently emerging in the heritage domain. It was initially created by researchers at TNO ICT (Niet 2009). The model focuses on two dimensions:

- The organizational model behind the service (open vs. closed)

- How the target audience uses the services and how data is reused

Fig 1: Social Web services in the cultural heritage domain.

These services can be grouped in seven clusters.

- ‘On demand’ digital archive. The brown dots. Here, the focus lies with providing access to a collection. User interaction is not the primary focus.

‘Social tagging/rating’. The yellow dots. Crowdsourcing offers a way for heritage organizations to gather metadata that could improve access and, at the same time, offers a platform for archives to actively engage with users. Well known examples include steve.museum (http://steve.museum), Open Plaques (http://www.openplaques.org) and Flickr the Commons (http://www.flickr.com/commons).

Enriching the ‘Offline’ museum visit. The dark turquoise dots. This cluster includes a great variety of interactive presentations, in and outside museum walls, that have a link with the collection or current exhibition.

Enriching the ‘On-line’ museum experience. The red dots. This cluster includes a variety of services aimed at a broad audience. The primary focus is to add value to the existing on-line presence of heritage organizations. Syndication (where content is placed on third party Web sites) is often used. Widgets, Facebook groups and collaborative video platforms are good examples.

‘Collaborative storytelling’. The green dots. Collaborative storytelling focuses on the ability for visitors to share their stories. This can be done on the Web site of the institution (as in the case of the Maine Memory Network, for instance) or on a Web site run by communities of users. My Brighton and Hove (http://www.mybrightonandhove.org.uk) is a good example of the latter.

Distributed research. The light blue dots. Initiatives in this cluster focus on professional use. This includes a wide variety of users that invest considerable time in studying history. Also, professionals working in the heritage domain that use LinkedIn to share news, information etc. fall in this category.

On-line marketplace. The purple dot. This is an example where art can be bought on-line; in this case the Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage is selling works of art through a dedicated eBay store.

Encouraging user engagement is a central notion in all of the example services. Within the scope of Images for the Future, two pilots carried out in 2009 will be described in more detail: the Waisda? Video Labeling Game, focusing on Crowdsourcing, and Gas in Beeld, focusing on collaborative storytelling. Below, the results of both pilots are discussed.

Pilot 1: Video Labeling Game

Different aspects of both institutional and user involvement in the abovementioned ‘shared information space’ are explored in this pilot. It was initiated by the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision (the largest audiovisual archive in the Netherlands), the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and KRO Broadcasting. In the spirit of ‘games with a purpose’, the Waisda? (which translates to What’s that?) Video Labeling game was developed. It invites users to tag what they see and hear, and receive points for a tag if it matches a tag that their opponent has typed in (within a time frame of ten seconds). The underlying assumption is that tags are probably valid if there’s mutual agreement, and that enabling social tagging of audiovisual content in the form of a game motivates the ‘crowds’ to actually contribute tags. Waisda? uses links with popular television programme Web sites, Twitter, and social networks to reach the necessary audience. Since May 2009, the game has been played by hundreds of people and within 7 months, over 350k tags have been added to over 600 items from the archive.

Within a six months pilot, Waisda? initially aimed to explore whether a game could attract and activate a substantial audience and gather enough tag entries as rough data for further research. The eventual goal is to add fine-grained descriptive tags to improve meaningful access to large repositories of videos. An extensive evaluation of the pilot provides evidence that crowdsourcing video annotation in a serious, social game setting can indeed enhance retrieval of video in archives. It features success factors organizations need to take into account in setting up services that aim to actively engage their audiences on-line.

Fig 2: Waisda? homepage (users select one of four thematic ‘channels’)

Fig 3 The Waisda? game environment.

Waisda? managed to attract a large audience to its Web site (http://www.waisda.nl). Since its launch on the 19th of May, 2009, Waisda? was consulted by 9,198 unique visitors and gathered 340,551 tags describing 604 items, added by a total of 2,296 players. The Web site was consulted 12,297 times; 3,61 pages were visited on average. Only 38% of the visitors didn’t look further than the home page. Average game sessions lasted for 6 minutes and 45 seconds. By the 3rd of November, 2009, 42,068 unique tags have been added. The total number of tags added by players is 340,551, of which 40.3% (137,421 tags) consist of matching tags (tags added by two or more players within a time frame of 10 seconds.

More than 70% of the traffic on the Web site was generated through referrals by external Web sites. The three main referring Web sites also resulted in the lowest bounce rate, suggesting that visitors that arrive at the Web site through an external link are more specifically interested in the content and the project than direct visitors. Also, increases in the number of registered players are strongly related to promotional activity. Lastly, there is a clear relationship between the most popular and heavily tagged content, and the efforts by the Dutch public broadcaster – and project partner – KRO to promote playing Waisda? with this content through their very popular programme Web site. These results show the importance of extensive external promotion of a project like this, aimed at relevant target groups. This implies that Waisda? should target these audiences through existing and popular channels related to the content available within the game, or communities interested in tagging and innovative projects within the cultural heritage sector. For a continuation of the project, and to have video labeling as a standard service, it is important to actively collaborate with Web sites from broadcasters delivering content for Waisda? - for example, by posting an article to notify potential players, or making an explicit call to action or a contest.

The majority of players (1,051, or 45.8%) added between one and ten tags. A smaller number of players (810, 35.3%) added between ten and a hundred tags, and less than half of that number (372, 16.2%) added between a hundred and a thousand tags. Only a few players added more than a thousand tags (63, 2.7%), but together they were responsible for adding the largest number of all contributed tags. The longest session lasted about three hours, in which one player added 3,329 tags. This indicates that a project like Waisda? shouldn’t aim only for a wide audience, but should also find a way to specifically target these ‘super taggers’.

Involving Users

User research has shown – and supports earlier research on similar projects – that altruism is an important motivation for playing Waisda?. Therefore the ‘about’ section of the Web site should emphasize the benefits of player activity to (public) accessibility of the content and further research on tagging. The current research on tagging shows that taggers who are explicitly invited to help an institution by tagging are notably more active. To further promote Waisda? a strategy that targets these altruistic players should be developed. Besides that, players should be given a sense of the impact of their activity: institutions need to experiment with ways to demonstrate the usefulness of the tags for searching through the content.

Apart from altruism, the evaluation showed that the video content itself has also proven to be a motivational factor for players to play the game. The most popular channel on Waisda? contains a popular Dutch reality show (http://boerzoektvrouw.kro.nl), “Farmer Seeks a Wife,” with a weekly viewing audience of millions. To attract a broad constituency of users, it is important to expand the diversity of the content available on Waisda?, and experiment with different types of content.

Research has shown a particular interest from users in popular talk shows reflecting on recent events, programmes aimed at children, and historical footage. Also, it is important to keep the content fresh. For example, at the moment there are already 29 items that contain over 2.000 tags.

Literature studies, user research and practical experience with Waisda? have shown that both intrinsic and extrinsic factors play a role in the motivation of players. The recent literature also supports the initial concept of the Waisda? project, that assumes a game setting is a good way to motivate people to tag (audiovisual) archive material. This shows it is important to make sure that the game design also motivates players who are not particularly interested in tagging per se, or feel that in general tagging is too much of an effort. Besides that, it is crucial to provide good game design and game play, so the altruistic players also enjoy Waisda?.

Ideally, the intrinsic and extrinsic factors come together in the game and interface design. Although Waisda? can be played in solitude (against so-called bots), user research has shown that the vast majority of players prefer playing against others. This shows the importance of a substantial and active community of players. Next to the abovementioned promotion on external Web sites, organizing a contest on Waisda? has shown how handing out prizes can motivate players. It is certainly worthwhile to further experiment with this. Apart from that, social media can also play an important role to position Waisda? as a serious social game; i.e., linking to existing social networks such as Facebook, Twitter and Hyves. The integration with Twitter is already carried out within the pilot.

Tag Quality

Analyses of the most recent database dump of tags shows that 5.8% of the tags match with the terms in the GTAA thesaurus the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision uses to classify their collection. Apart from this, 23.6% corresponds with Cornetto, a linguistic database that contains the bulk of all official Dutch words. Since only a small number of tags is present in both databases (1,135, or 2,7%), it can already be assumed that almost a third of the tags are existing and correct words. A professional senior cataloguer (employee of the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision) has judged the tags added to two episodes on their usefulness. The selected episodes were the best-tagged episode from the popular Dutch reality show mentioned before, with 19,322 tags added to it, and an episode tagged with an average number of tags - a documentary series about a former news correspondent situated in the U.S. returning to the Netherlands - with 738 tags.

- Looking at the best-tagged episode, 45% of the tags were deemed useful, with 27.45% having low and 11.76% having high accuracy.

- The averagely tagged episode contained 72.69% tags deemed useful .with 26.39% having low and 19.44% having high accuracy.

The senior cataloguer noted that in general the useful tags describe the material in a different way than keywords that catalogues add do. First, the tags focus on describing what is seen and heard within a programme, while the professional metadata for audiovisual content focuses on the subjects that a programme refers to. Apart from that, the tags also describe instances from a programme, instead of a logical segmented part and/or entire episode. The fact that the crowdsourced tags for the audiovisual material differ from professional metadata is no surprise, and possibly even an indication that the tags contribute to bridging the semantic gap (the gap between professional descriptions, based on a closed vocabulary, and the free search terms used by potential audiences to find the material). However, further research on the usefulness of the tags is needed; for example, by conducting search experiments with different types of end users.

To describe the episode as a whole, only two tags from the top 20 most-added tags of the averagely tagged episode proved to be useful. For the best-tagged episode, none of the top 20 tags was deemed useful to describe the complete episode. Tags added to the documentary series episode were notably more often useful than tags added to the reality show. They were more defining and specific. The reality show contained more general tags and lacked specificity. These findings contradict the assumption that the more often a tag is added to an episode, the higher the usefulness of this tag is to the audiovisual archive. The content seems to influence the specificity of the tags that are entered. It is also striking that in the case of the reality show, more tags correspond with the GTAA or Cornetto database, but still the tags added to the documentary series episode were deemed more useful by the professional senior cataloguer. This suggests that a programme containing a multitude of specific items or topics might attract more specific and useful tags. The way content seems to influence the way it is tagged demands further research. Since the metadata for audiovisual collections mainly describe collections only on an item level, time-based metadata like tags can result in important progress in servicing media professionals looking for specific fragments. It is therefore important to further develop this research to discover how and to what degree the tags can be used within the professional metadata in the catalogue of the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision.

Conclusion: Pilot 1

Waisda? relied on extensive external promotion aimed at relevant target groups to reach a critical mass of users. Collaboration with existing and popular channels related to the content available within the game is crucial for maturing the project from a pilot into a full-scale service. However, the exceptional effort put into the game by a small number of users indicates that a project like Waisda? shouldn’t aim only for a wide audience, but should also find a way to specifically target these ‘super taggers’.

Altruism proved to be a crucial motive for playing the game, but altruistic players should be given a better sense of the impact of their activity through demonstrations of the usefulness of the tags for searching through the content. Apart from altruism, the video content itself and the gaming element have also proven to be important motivational factors that need constant care and improvement. Although Waisda? can be played in solitude, the vast majority of players prefer playing against others. To ensure a substantial and active community of players social media can play an important role in positioning Waisda? as a serious social game; i.e. linking to existing social networks such as Facebook, Twitter and Hyves.

It can already be assumed that almost a third of the tags are existing and correct words. A professional senior cataloguer has judged the tags added to two episodes on their usefulness, and deemed useful 45% of the tags from the best-tagged episode and 72.69% of the tags of an averagely-tagged episode. The fact that the crowdsourced tags for the audiovisual material differ from professional metadata is no surprise, and possibly even an indication that the tags contribute to bridging the semantic gap. However, further research on the usefulness of the tags is needed; for example, by conducting search experiments with different types of end users. Since the metadata for audiovisual collections mainly describe collections only on an item level, time-based metadata like tags can result in important progress in servicing media professionals looking for specific fragments. It is therefore important to further develop this research to discover how and to what degree the tags can be used within the professional metadata in the catalogue of the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision.

Pilot 2: Gas In Beeld (“Natural Gas in Images”)

On May 29th, 1959, underneath "farmer Boon's" farm near the Dutch rural town of Slochteren, a huge subterranean natural gas reserve was discovered. At first sight, the discoverers approximated the size of the field at about 300 billion cubic meters. Only long after the discovery, measurements pointed out that they were slightly off: the total size of the "gas bubble" (as it was coined) was more than 3000 billion cubic meters, over ten-fold the initial approximation. It didn't take long before a large quantity of Dutch households was connected to a widespread system of gas pipes for cooking, heating and lighting.

The discovery proved to be a true landmark in terms of economic profits, independence from oil imports, and household convenience. Although the discovery was made in Slochteren, this community has rather mixed memories about the gas find. First, they didn't benefit from living on top of the 'bubble,' but had to endure numerous drillings and small earthquakes and land subsidences as a result of that. Moreover, a large number of coal vendors had to close up shop due to the collapsing demand for their goods - gas was both cheaper and more convenient. All in all, it hasn't been just sunshine and roses for the local communities, and nobody seemed to take any notice of that. This made an interesting starting point for a digital storytelling project to uncover what has been hidden for 50 years. And that was exactly what the project Images of Gas: Stories of Slochteren aimed for: to collect and publish true stories told by the local community.

About the Project

In 2009, one of the partners in Images for the Future, the Dutch Association of Public Libraries (VOB) and Knowledgeland Foundation started a pilot with a so-called ‘vanguard library’, Biblionet Groningen. This collaboration aimed at selecting and contextualizing audiovisual materials from Images for the Future collections around the theme "50 years of natural gas". This pilot was part of the grand-scale anniversary program "G50".

Part of this pilot was the development of a Web site (http://www.gasinbeeld.nl) which was developed for everyone interested in the theme, but with special tools for educational purposes, such as an interactive timeline and contextual information. A large collection of audiovisual heritage was made available on this Web site from the archives of GAVA (Groningen Audiovisual Archive), NAM (National Oil Society), GasTerra (natural gas trade) and the IFTF partners Film Museum and the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision (see case study Waisda?, above). The main goals of the pilot were:

- To bring forward the information function of libraries (digital and physical)

- To tighten the bonds between libraries and education (and other public services)

- To familiarize students with the use of new media applications in educational settings

- To support teachers in using new media applications in their practice.

In collaboration with the Slochteren local library and Biblionet Groningen, all people involved in their local history (grandfathers and grandmothers, and their children and grandchildren) were invited to tell their stories. What was the impact of the discovery of natural gas within families, on working conditions and on the Groningen region? In the anniversary programme, local library staff helped to approach the target audiences. Stories were recorded on digital video cameras. In order to gather as many stories as possible, a physical installation, the ‘storytelling pavilion’ was created. It was installed right on top of the “gas bubble”. Visitors could:

- View over 150 historical videos about the natural gas bubble either on a 15-meter-wide screen or on one of the computer screens inside the pavilion

- Record their personal stories on camera. A professional video crew assisted them. All captured stories were published on the Web site and screened at the large screen on the pavilion

- Remix their recorded stories with archive materials and create a whole new digital story about their personal experiences with gas

- Take their stories home on a free USB stick

Fig 4: visitors in front of the pavilion, now showing one of the newly captured stories

Fig 5: people inside the pavilion, remixing their own stories with archive materials

Remixing Video Material

One of the more complex aspects of the project was copyright. Working with two separate groups of content providers proved to be a challenge in terms of copyrights. First, the archives which provided the audiovisual material: GAVA (Groningen Audiovisual Archive), NAM (National Oil Society), GasTerra (gas trade) and the Images for the Future partners Eye Film Institute and the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision: to allow remixing and sharing of the materials, archives had to make sure that the necessary copyrights were cleared.

Initially, not all these archives could allow the use of the original audiovisual material for remixing purposes. Eventually it was decided to create low-res proxies that could be made available under less strict IPR restrictions. The clips were added to the Gas in Beeld Web site under a Creative Commons license. The Creative Commons license used Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported that allows remixing and sharing of the recorded stories under specific conditions.

The second group providing content were the end users of the storytelling project: the visitors to the pavilion, who recorded their stories on camera and/or remixed audiovisual material. In both cases these visitors were the rightful owners of the video content. To participate in the project, they had to agree that the content they produced would be placed on-line under the aforementioned Creative Commons license.

Results

The local library of Slochteren became the center of attention and a place where residents could meet and share stories. The continuity of this new role of the library is uncertain. The anniversary of the “gas bubble” was a unique event. Turning these activities into structural practice is a challenge for a small institution depending mainly on volunteers.

One of the expected results of the project was engaging the local community with their own local history. The project succeeded in reaching this goal. The pavilion was visited by a wide variety of social groups. Seniors and other locals recorded their memories and stories about the “Gas bubble”. These stories are unique and sometimes quite moving. One of the most striking stories is that of alderman Scheidema. He shared on camera the story of his life in Slochteren and even brought in his high school paper about natural gas. In this paper, Scheidema wrote about the expected future possibilities of the ‘gas bubble’. Ninety pupils of an elementary school reenacted on camera old stories about the ‘Gas bubble’. Throughout the summer a huge number of people visited the pavilion to watch the video stories and archives.

The Web site succeeded in attracting a sizeable audience within a limited period. The Web site had over 5,600 unique visitors and counted 45,044 page views. These aren’t huge numbers, but given the limited time the Web site was on-line (about 4 months) and the rather specific (and to some extent, local) theme, we’re not dissatisfied. More important, the Web site managed to grasp the attention of most visitors, with an average visit duration of 4:58 minutes - long enough to view at least two to three stories.

In terms of press coverage, the project managed to attract quite some press interest:

- An article featured in Trouw, a Dutch national newspaper, as well as several smaller news stories in local papers

- A news item on Jeugdjournaal, a daily Dutch TV news show for youth

- Several radio items on Dutch national radio broadcasts.

Lessons Learned

First, it proved difficult to instruct and manage the employees of the local participating library. The technology involved in digital storytelling was all new and even to some extent frightening to them. For future projects, we’ve learned that it is of key importance to structurally support and coach the local volunteers and librarians. We underestimated the importance of these factors, leading to a lack of engagement and community involvement in the project. Had we foreseen this, we would have probably been more successful in engaging the local community.

Secondly, the hired pavilion crew wasn't used to working with the local and 'low tech' community they were confronted with in Slochteren. The crew was trained for working with a younger, more digitally oriented audience. Involving an 80-year-old local (let alone her older sister) in a digital storytelling project means putting a lot of effort in setting these people at ease with technology like computers, editing software and digital cameras.

Finally, it takes a lot more than a one-off digital storytelling project to position a local public library such as the one in Slochteren as innovator in information services. We managed to temporarily bring this institution to the attention of a local, regional and national audience in terms of ‘unexpected’ new services, but soon after the project ended, the library returned to its traditional core business of lending books. The library could have been more visible as one of the driving factors of “Natural gas in Images”, making the public more “demanding” in terms of what one could expect of their library and the library perhaps more willing to indeed innovate with its services.

Conclusion: Pilot 2

As we’ve tried to exemplify in the above paragraphs, digital storytelling as a public service can deliver interesting results in terms of local community involvement. We were satisfied to see that a lot of locals invested time and effort to visit the pavilion and watch old audiovisual material about an episode of their own history.

Others were prepared to record their own stories on camera and have those remixed with old material, thus making their stories available for everybody interested. Involving a local, ‘low tech’ community in a project like this doesn’t come cheap, though. We put a lot of effort in enthusing and managing the library crew (consisting largely of volunteers) who were to some extent “afraid” of technology. Also, during the execution of the pilot, it became clear we needed a crew who can really encourage a community with specific needs and ideas to come and add their stories. Lastly, it’s highly uncertain whether a small library such as the one in Slochteren is able to support such kinds of activities as a structural practice. To engage in a project like this even once has proven to be a real challenge for a small institution depending mainly on a voluntary workforce. Nonetheless, the library has been at the center of a whole different kind of attention, be it for just a short while.

This doesn’t mean that digital storytelling is no longer an interesting theme for Images for the Future. We would like to further develop it as a method to involve people in their history in a smart and fun way. The lessons learned from this project will without doubt help us to focus and improve on further developments and new ideas for digital storytelling projects are already in the making.

Conclusions

New technology makes it possible for cultural heritage organizations to engage with their audience in novel ways. The model presented in this paper maps emerging practices according to the organizational model and according to the way the audience is using these services. Images for the Future is working on a variety of (pilot) services, two of them described in this paper (Oomen 2009).

Both illustrate some of the preconditions that need to be in place to guarantee successful user engagement. Both crowdsourcing and collaborative storytelling initiatives rely on a continuous stream of users in order to retain interest. Projects need to invest ample time in reaching out to existing communities. Currently, the Images for the Future project partners are investigating how these pilots could turn into full-scale services. In the case of Waisda?, the aim is to tap into the viewing audience of popular television series. In the case of mobilizing local communities around storytelling (as in Gas in Beeld), a pivotal role can be played by libraries. Future work will also include creating links between the user-generated knowledge and existing information systems, such as catalogues and other sources that are available on-line (e.g. Linked Data). This will shape the next generation information eco-systems in the cultural heritage domain.

References

Niet, Marco de, Lieke Heijmans en Harry Verwayen (2009). Business Model Innovatie Cultureel Erfgoed. DEN, Kennisland, OCW.

Oomen, J., et al. “Images for the Future: Unlocking the Value of Audiovisual Heritage”. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Museums and the Web 2009: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2009. Consulted February 24, 2010. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2009/papers/oomen/oomen.html